Introduction

Multiple synonyms, including coccydynia, coccygodynia, and tailbone pain, are known as coccyx pain.[1] Simpson introduced the term coccydynia in 1859, and Foye has referred to coccyx pain as the "lowest" (most inferior) site of low back pain.[1][2] There are many causes of coccygeal pain, ranging from musculoskeletal injuries (such as contusions, fractures, dislocations, and ligamentous instability) to infections (osteomyelitis) and fatal malignancies (such as chordoma).[1]

Although many cases are self-limiting and resolve with little or no medical treatment, other cases are notoriously persistent, are challenging to treat, and are associated with severe and disabling chronic pain. Patients often report difficulty getting a specific diagnosis for the cause of their coccyx pain and note that their treating clinicians seem dismissive of this condition.[2] Clinicians should understand the various modern options available to diagnose and treat coccydynia. Further, patients should be referred to a specialist if the etiology remains unclear or the patient fails to get adequate relief. The overall scope of treatment includes avoiding exacerbating factors (sitting), using cushions, taking oral or topical medications, and administering pain management injections under fluoroscopic guidance. Only a small percentage of patients with coccydynia require surgical treatment, which is coccyx resection (eg, coccygectomy).[1]

Anatomy

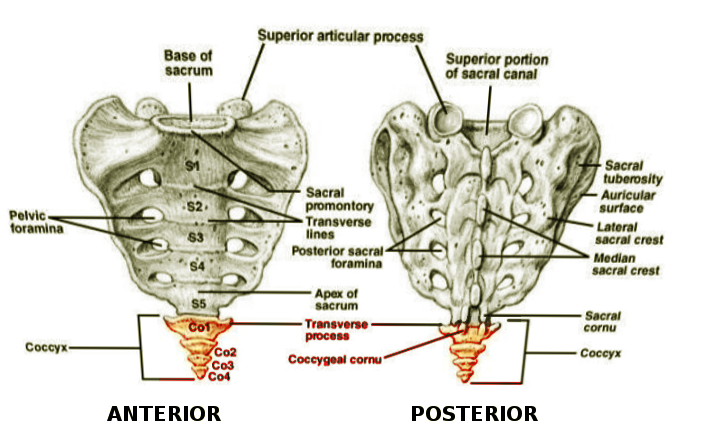

The coccyx is the terminal region of the spinal column. Although "tailbone" implies that this is a single bone, it consists of 3 to 5 separate vertebral bodies, with substantial variability regarding whether they are fused. The coccyx articulates with the sacrum through a sacrococcygeal joint (including a fibrocartilaginous intervertebral disc and bilateral zygapophysial [facet] joints). The sacrococcygeal and intra-coccygeal joints allow for a modest amount of coccygeal movement, typically forward flexion while weight-bearing (sitting).[1] The coccyx is a Greek word that means the beak of a cuckoo bird, as the side view of the tailbone resembles the side view of a cuckoo bird's beak.[3][4]

On the anterior surface of the coccyx, the following muscles gain attachment: levator ani, iliococcygeus, coccygeus, and pubococcygeus. On the posterior coccygeal surface, the gluteus maximus is attached. Also attached to the coccyx are the anterior and posterior sacrococcygeal ligaments, which continue the anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments. Bilateral attachments to the coccyx include the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments.[5] Besides being an insertion site for these muscles and ligaments, the coccyx is also attached to the anococcygeal raphe (which extends from the anus to the distal coccyx, holding the anus in its position within the pelvic floor).

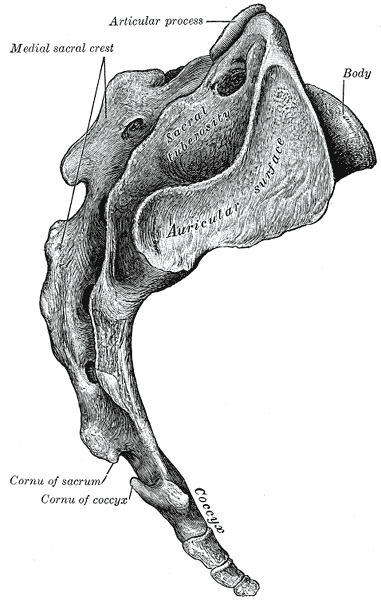

Functionally, a tripod is formed by the bilateral ischial tuberosities (at the right and left inferior buttocks) and the coccyx (in the midline). This tripod supports weight-bearing in the seated position.[6] The nerves of the coccyx are not usually well described in anatomical textbooks, but include somatic nerve fibers and the ganglion impar, which is the terminal end of the paravertebral chain of the sympathetic nervous system.[7][8] The plural of the coccyx is coccyges or coccyxes (see Images. Sacrum and Coccyx, Lateral Surface and Coccyx Vertebrae).

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Direct vertical trauma, repetitive microtrauma, childbirth, and idiopathic etiologies are common causes of coccyx pain. However, more serious underlying causes must be excluded, such as infections (including soft tissue abscess and osteomyelitis) or malignancy (including chordoma, which has a high mortality rate).[1][9] Also, coccydynia can be referred pain due to lower gastrointestinal or urogenital disorders.[10] Degeneration of the sacrococcygeal and intercoccygeal discs and joints has also been shown to cause coccyx pain.[9] Other causes, such as lumbar disc prolapse, have been reported as possible etiologies in a limited number of cases.

The outcome of direct vertical trauma to the coccyx can vary from contusion to fracture-dislocation of the coccyx. Traumatic or nontraumatic compromise of the coccygeal ligaments can result in coccygeal dynamic instability (excessive movement of the coccyx during weight-bearing or while sitting). Abnormal mobility of the coccyx can result in coccygeal pain. Abnormally mobile coccyges can be either hypermobile (due to lax ligaments) or hypomobile (rigid). The coccyx may be subluxated anteriorly, posteriorly, unstable, or dislocated.[11]

Coccyxes of specific shapes are more predisposed to coccydynia than others.[12] Abnormal coccygeal morphology or position predisposing to coccyx pain includes abnormal scoliotic deformity (lateral deviation) or an excessively flexed or extended coccyx.[1] A distal coccyx bone spur (spicule) may cause pain when the skin is pinched beneath the spur during sitting.[13] Idiopathic coccydynia is a 'diagnosis of exclusion' after careful screening for identifiable causes.

Epidemiology

Factors related to the high risk of developing coccydynia are female sex and obesity, as body mass index may affect how a person sits or the amount of weight placed upon the coccyx.[10][14] Coccydynia is 5 times more common in females than in males.[6][11][15] This difference between sexes appears to be due to anatomical and hormonal differences.[16] Rapid weight loss has been reported to be a risk factor for coccydynia due to the loss of the cushioning effect of adipose in the buttock region. Other reported risk factors include osteoarthritis, osteomyelitis, and contact sports.

History and Physical

The typical presentation of coccydynia is pain localized to the coccyx. In traumatic coccydynia, there will be a preceding history of trauma followed by an acute onset of pain. Notably, childbirth has been shown to cause fractures.[4] The pain will often have an insidious onset in idiopathic coccydynia without any obvious or specific precipitant. Due to other causes, a careful and thorough history will often suggest the possible etiology in coccydynia.

Coccydynia is typically worse, especially in a partly reclined (backward-leaning) position.[1] The pain is usually exacerbated by prolonged sitting and cycling.[10] Standing up from the seated position may cause a temporary but severe increase in coccyx pain.[1] Other exacerbating factors may include standing for a long time, sexual intercourse, and defecation.[6] Physical examination includes inspecting the overlying skin for signs of infection or other differential diagnoses such as pilonidal sinus and hemorrhoids.

"Foye Finger" for Coccydynia

This is comparable to "Fortin finger," where Dr Fortin published on the usefulness of having patients with sacroiliac joint pain point to their site of pain, thus helping to distinguish this from lumbar pain generators.[17] Similarly, Dr Foye recommends asking patients to point with 1 finger to their worst site of pain, which in coccydynia patients will be far more inferior than the more common causes of low back pain (located up in the lumbosacral spine), and more midline than buttock pain syndromes (such as sacroiliac pain and piriformis pain).[1]

External palpation usually reveals localized tenderness focally over the coccyx. A rectal examination may be useful in some patients to evaluate the degree of coccygeal mobility and will typically elicit pain when manipulating the coccyx.[14] Beyond evaluating the coccyx itself, assessing for other sources of musculoskeletal pain is often helpful by performing a physical examination of the sacroiliac joints, ischial bursae, and piriformis muscles.

Evaluation

Coccyx fractures can be categorized into types I–III based on pathogenesis, namely flexion, compression, and extension:

- Type I: Flexion fracture, typically occurring due to a fall or direct impact

- Type II: Compression fracture, involves vertical fracture lines affecting the separate coccygeal vertebrae.

- Type III: Extension fracture, occurring primarily as obstetric fractures caused by forced extension during labor.[4][18]

Standard anteroposterior radiographs may demonstrate coccygeal scoliotic (lateral deviation) deformities. Lateral views are always indicated as coccyx curvature can be classified into 4 different types:

- Type I: The coccyx is slightly curved forward.[12]

- Type II: The coccyx is pointed straight forward.[12]

- Type III: The coccyx has a sharp forward angulation.[12]

- Type IV: The coccyx shows subluxation at the sacrococcygeal or the intercoccygeal joint.[4][12][4][19]

From the lateral radiographs, the examiner can assess the intercoccygeal angle, the measured angle between the coccyx's first and last segment, as Drs Kim and Sum proposed. This is used to assess the anterior angulation deformity of the coccyx. An increased intercoccygeal angle (increased forward angulation) has been reported as a possible etiology of coccydynia.[11]

- Dynamic radiographs (sitting and standing): Dr Maigne, in France, invented the idea of seated x-rays of the coccyx to see the coccyx position while the patient with coccydynia was most symptomatic, which typically occurs while sitting. The clinician can objectively measure the amount of change by comparing the coccyx position while sitting versus the standing position. These coccygeal movements are measured as changes in the coccygeal angle (amount of flexion) and luxation (amount of listhesis at each coccygeal joint).

- These studies allow the classification of patients with coccydynia into groups based on coccygeal luxation and mobility (hypomobile, hypermobile, and normal mobility). The normal range of coccygeal mobility is between 5º and 20º.[20][21] Thus, if sitting causes a change in the coccygeal angle of fewer than 5º, this is hypomobility. Conversely, if sitting changes the coccygeal angle by 20º or more, this is hypermobility.[20]

- The patients responding best to manual treatments are those with normal coccyx mobility, while those with immobile coccyxes had poor results with manual therapies.[22] In those without coccydynia, the change in luxation (listhesis) at the coccygeal joints is less than 25% of the anterior-posterior depth of the coccygeal vertebral body.[23] Seated radiographs of the coccyx often reveal abnormalities that were missed on nonseated radiographs.[24]

- A computed tomography scan of a normal adult coccyx shows variability in the fusion of the sacrococcygeal and intercoccygeal joints. Female coccyges are more often shorter, straighter, and more retroverted.[25]. However, these anatomic findings should be interpreted in correlation with a thorough history and detailed clinical examination before determining whether the findings are (or are not) the cause of the patient's pain.[26]

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to assess the anterior curvature of the coccyx, the fusion of the sacrococcygeal and intercoccygeal joints, as well as the presence of a distal coccyx bone spicule (spur).[27] These anatomical findings can either be a precipitant or a consequence of coccydynia.[27] Overall, MRI can be a helpful diagnostic test for patients with coccydynia.[28] MRI can also assist in screening for local malignant and nonmalignant tumors.[1]

- Coccygeal discogram involves injecting contrast and local anesthetic into the sacrococcygeal region to determine the specific site of pain.[20] This can serve as a diagnostic and therapeutic procedure.

- Nuclear medicine bone scans are typically only used in patients with coccydynia in whom a search for malignancy or infection (eg, osteomyelitis) is warranted.[1]

- Routine blood tests may help in rare cases, such as when suspected etiologies include infection, malignancy, gastrointestinal, or urogenital problems.

Treatment / Management

Many patients with coccydynia experience relief of symptoms within weeks or months of onset, whether or not they receive medical treatment. The success of conservative treatment has been reported to be 90%.[4][6] Lifestyle changes, including weight loss strategies, should be offered to all obese patients experiencing coccydynia. The following modalities can be offered in acute and chronic cases:(B3)

Acute Coccydynia

- Oral or topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can be helpful acutely to decrease both pain and inflammation.

- Cushions on the patient's chair can make sitting more comfortable. A cushion with a wedge-shaped cut-out beneath the coccyx can result in the coccyx hovering over the empty area, thus resulting in less coccygeal weight-bearing and less coccygeal pain. Other cushion options include U-shaped and circular (eg, donut) cushions.[1]

- Pelvic floor physical therapy may benefit patients with substantial muscular pain within the adjacent para-coccygeal muscles.[1] Correct sitting posture can also be assessed and improved.

- Kinesiotaping has also been shown to be helpful for patients.[8][29]

- Piriformis and iliopsoas muscle stretching can be beneficial as well. [16][29]

- Shockwave therapy tailored to the patient's pain tolerance has been shown to improve long-term success and recurrence rates.[29]

- Salmon calcitonin is effective for coccygeal fractures.[4]

- Modalities: Cold or hot compresses may be helpful in some patients. However, be cautious to avoid injury to the skin by causing skin temperatures resulting in freezing or burning injuries.

- Fluoroscopy-guided steroid injections: These anti-inflammatory injections can benefit patients with coccydynia that has been present for less than 6 months.[30] (A1)

Chronic and Refractory Coccydynia

- Manipulation under anesthesia, with or without local anesthetic and corticosteroid injection: Manipulation may help relieve ligamentous pain or pain due to muscular spasms. Different manual treatments have been reported in the literature, including levator ani massage, levator ani stretch, and joint mobilization.[22] The levator ani massage and stretch have been reported to yield better outcomes than the joint mobilization modality.[22]

- Transrectal osteopathic manipulative therapy has also been shown to be effective in treatment.[31]

- Ganglion impar sympathetic nerve block with local anesthetic (even without corticosteroid) can provide some patients with complete and sustained resolution of symptoms.[32][33][34] Some patients may require repeat injections. The addition of corticosteroids may give additional relief. There are a variety of techniques for performing ganglion impar injection.[35][36][37][38] Ganglion impar sympathetic nerve block is especially effective in cases of cancer-related pain.[8]

- Pelvic floor physical therapy can be helpful for coccydynia, including in patients who have persistent pain despite coccygectomy.[39]

- Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (external using 2 cutaneous probes or internal using 1 cutaneous probe and one intrapelvic probe) may be used.[6]

- Spinal cord stimulation may be worth considering for some patients with coccydynia.[6]

- Psychotherapy can be helpful when a nonorganic etiology is suspected.[15] However, note that the psychological profile in patients with coccydynia is similar to that of other groups of patients, so it is important not to assume that coccydynia is due to psychological causes.[2][40] (B2)

Coccygectomy

Coccygectomy involves resection (ie, removal) of the coccyx. This treatment is usually reserved for the small percentage of patients who fail to get adequate relief from nonsurgical care.[1][41] Partial or total coccygectomy has reportedly been beneficial in cases of both traumatic and idiopathic coccydynia after conservative measures were unsuccessful.[12][42][43] Postoperative complications after coccygectomy include local infection, pelvic floor prolapse (sagging), retained coccygeal fragments, and ongoing pain despite the surgery.[1][9] Endoscopic coccygectomy was introduced in 2022 as a minimally invasive option for coccygectomy.[44](B2)

Differential Diagnosis

The following conditions can result in pain in the coccyx region that should be differentiated from coccydynia:

- Sacroiliac joint pain or inflammation

- Pilonidal cyst with abscess or sinus

- Sciatica

- Hemorrhoids

- Shingles of the buttocks or other forms of infection

- Piriformis syndrome

- Malignancy, eg, chordoma or chondrosarcoma

- Pelvic floor muscle pain

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients with coccydynia is variable. While most patients' symptoms improve or resolve with conservative (nonsurgical) care, other patients have notoriously persistent, even lifelong, coccyx pain. The severity of the pain and the functional impairment (the limited ability to sit) can be disabling. Coccygectomy historically had a relatively high postoperative infection rate, but it appears to be downtrending.[9] One study's results showed an infection rate of 4.7% due to aggressive dual antibiotic prophylaxis.[9] The infection risk is much lower with the modern minimally invasive approaches for coccygectomy. Even after tailbone removal, patients may have some degree of persistent pain.

Complications

One complication of coccydynia is that it may become a chronic pain syndrome. Early and thorough medical attention may help patients avoid delays in diagnosis and treatment. The hope is that this will help decrease the chances of the pain becoming persistent and disabling.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Most patients with coccydynia do not require surgical treatment (eg, coccygectomy, surgical amputation, or removal of the coccyx). However, monitoring the surgical site for infection in rare patients who undergo coccygectomy is essential. The coccygectomy site is very close to the anus, and infection is common. Current literature has shown infection rates under 5%.[9] Sometimes, infection at the post-operative site requires additional surgery to debride the infected tissue.

When pain persists despite coccygectomy, it is necessary to assess this body region with updated imaging studies (eg, radiographs and/or MRI). Sometimes, postoperative imaging studies reveal that the surgery inadvertently failed to remove one or more coccygeal bones or bony fragments.[45] At the Coccyx Pain Center at Rutgers New Jersey, Foye recommends using intraoperative radiography before completing coccygectomy to confirm removal of all intended coccygeal vertebral bodies and ensure a complete rather than inadvertent partial coccygectomy.[45]

Such intraoperative imaging studies could also ensure that the surgery did not create any pointy edges at the osteotomy site.[45] If discovered before surgical closure, the sharply angulated areas could be surgically smoothed down to minimize the risk of being a source of postoperative pain. Of note is that surgeons experienced in coccygectomy routinely palpate the bony edges at the end of the resection to confirm the absence of pointy edges.

Consultations

Referral to a specialist with expertise in treating coccydynia is warranted if the initial treating clinician is not knowledgeable about this condition, cannot provide the patient with a specific and accurate anatomic diagnosis, or cannot provide adequate relief. In refractory cases, the patient should be offered referral to a spine surgeon with expertise in coccygectomy.

Deterrence and Patient Education

If tailbone pain is severe or persists for more than one month, the patient should see a clinician with experience in evaluating and treating this condition. Suppose the first clinician a patient sees for coccyx pain is unfamiliar with this condition or does not take the patient's symptoms seriously. In that case, the patient should seek further medical care elsewhere.

Many patients have difficulty finding a radiology center familiar with performing the sitting-versus-standing x-rays of the coccyx, which are performed to view the coccyx when it is most painful (typically while sitting). Continuing to search for such a center is essential, as these radiographs can often reveal an abnormality (diagnosis) that nonseated x-rays fail to show.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Coccyx pain can have a profound impact on a person's daily life, limiting the patient's ability to sit, move, or participate in routine activities. This type of pain can stem from a variety of causes, including trauma, childbirth, prolonged sitting, infection, malignancy, or idiopathically. Diagnosis starts with a history and physical. Treatment often begins with conservative approaches like anti-inflammatory medications, supportive seat cushions, and physical therapy focused on pelvic floor and postural correction. If symptoms persist, targeted pain interventions—such as corticosteroid injections or ganglion impar blocks—may be appropriate. In rare, severe cases, surgery may be considered. Alongside physical treatments, helping patients adjust their posture, activity levels, and addressing the emotional toll of chronic pain is essential for comprehensive care.

Successfully managing coccyx pain often requires close collaboration among a range of healthcare professionals. Each team member—whether a clinician, physical therapist, pain specialist, behavioral health specialist, or surgeon—brings important functions into the patient’s care plan. Working together allows the team to develop personalized strategies that align with the patient’s symptoms, lifestyle, and overall health goals. Regular communication, shared decision-making, and coordinated follow-up contribute to better outcomes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Sacrum and Coccyx, Lateral Surface. This image shows the anatomy of the sacrum and coccyx, including the articular process, medial sacral crest, and the cornu of the sacrum and coccyx.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Foye PM. Coccydynia: Tailbone Pain. Physical medicine and rehabilitation clinics of North America. 2017 Aug:28(3):539-549. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2017.03.006. Epub 2017 May 27 [PubMed PMID: 28676363]

Foye PM. Stigma against patients with coccyx pain. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.). 2010 Dec:11(12):1872. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00999.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21134124]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSugar O. Coccyx. The bone named for a bird. Spine. 1995 Feb 1:20(3):379-83 [PubMed PMID: 7732478]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZhang Y, Gao G. Progress in the diagnosis and treatment of fracture‑dislocation of the coccyx (Review). Experimental and therapeutic medicine. 2025 Jul:30(1):127. doi: 10.3892/etm.2025.12877. Epub 2025 May 6 [PubMed PMID: 40396140]

Woon JT, Stringer MD. Clinical anatomy of the coccyx: A systematic review. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2012 Mar:25(2):158-67. doi: 10.1002/ca.21216. Epub 2011 Jul 7 [PubMed PMID: 21739475]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLirette LS, Chaiban G, Tolba R, Eissa H. Coccydynia: an overview of the anatomy, etiology, and treatment of coccyx pain. Ochsner journal. 2014 Spring:14(1):84-7 [PubMed PMID: 24688338]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKerr EE, Benson D, Schrot RJ. Coccygectomy for chronic refractory coccygodynia: clinical case series and literature review. Journal of neurosurgery. Spine. 2011 May:14(5):654-63. doi: 10.3171/2010.12.SPINE10262. Epub 2011 Feb 18 [PubMed PMID: 21332277]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLee SH, Yang M, Won HS, Kim YD. Coccydynia: anatomic origin and considerations regarding the effectiveness of injections for pain management. The Korean journal of pain. 2023 Jul 1:36(3):272-280. doi: 10.3344/kjp.23175. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37394271]

Perna A, Franchini A, Macchiarola L, Maruccia F, Barletta F, Bosco F, Rovere G, Gorgoglione FL. Coccygectomy for refractory coccydynia, old-fashioned but effective procedure: A retrospective analysis. International orthopaedics. 2024 Aug:48(8):2251-2258. doi: 10.1007/s00264-024-06236-y. Epub 2024 Jun 18 [PubMed PMID: 38890180]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePatijn J, Janssen M, Hayek S, Mekhail N, Van Zundert J, van Kleef M. 14. Coccygodynia. Pain practice : the official journal of World Institute of Pain. 2010 Nov-Dec:10(6):554-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2010.00404.x. Epub 2010 Sep 6 [PubMed PMID: 20825565]

Kim NH, Suk KS. Clinical and radiological differences between traumatic and idiopathic coccygodynia. Yonsei medical journal. 1999 Jun:40(3):215-20 [PubMed PMID: 10412331]

Postacchini F, Massobrio M. Idiopathic coccygodynia. Analysis of fifty-one operative cases and a radiographic study of the normal coccyx. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1983 Oct:65(8):1116-24 [PubMed PMID: 6226668]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDoursounian L, Maigne JY, Jacquot F. Coccygectomy for coccygeal spicule: a study of 33 cases. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2015 May:24(5):1102-8. doi: 10.1007/s00586-014-3753-5. Epub 2015 Jan 6 [PubMed PMID: 25559295]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMaigne JY, Doursounian L, Chatellier G. Causes and mechanisms of common coccydynia: role of body mass index and coccygeal trauma. Spine. 2000 Dec 1:25(23):3072-9 [PubMed PMID: 11145819]

Nathan ST, Fisher BE, Roberts CS. Coccydynia: a review of pathoanatomy, aetiology, treatment and outcome. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 2010 Dec:92(12):1622-7. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B12.25486. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21119164]

Blanco-Diaz M, Palacios LR, Martinez-Cerón MDR, Perez-Dominguez B, Diaz-Mohedo E. Physiotherapy approaches for coccydynia: evaluating effectiveness and clinical outcomes. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2025 May 26:26(1):514. doi: 10.1186/s12891-025-08744-3. Epub 2025 May 26 [PubMed PMID: 40420056]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFortin JD, Falco FJ. The Fortin finger test: an indicator of sacroiliac pain. American journal of orthopedics (Belle Mead, N.J.). 1997 Jul:26(7):477-80 [PubMed PMID: 9247654]

Maigne JY, Doursounian L, Jacquot F. Classification of fractures of the coccyx from a series of 104 patients. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2020 Oct:29(10):2534-2542. doi: 10.1007/s00586-019-06188-7. Epub 2019 Oct 21 [PubMed PMID: 31637549]

Daily D, Bridges J, Mo WB, Mo AZ, Massey PA, Zhang AS. Coccydynia: A Review of Anatomy, Causes, Diagnosis, and Treatment. JBJS reviews. 2024 May 1:12(5):. doi: e24.00007. Epub 2024 May 6 [PubMed PMID: 38709859]

Maigne JY, Guedj S, Straus C. Idiopathic coccygodynia. Lateral roentgenograms in the sitting position and coccygeal discography. Spine. 1994 Apr 15:19(8):930-4 [PubMed PMID: 8009351]

Maigne JY, Pigeau I, Roger B. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in the painful adult coccyx. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2012 Oct:21(10):2097-104. doi: 10.1007/s00586-012-2202-6. Epub 2012 Feb 22 [PubMed PMID: 22354690]

Maigne JY, Chatellier G. Comparison of three manual coccydynia treatments: a pilot study. Spine. 2001 Oct 15:26(20):E479-83; discussion E484 [PubMed PMID: 11598528]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMaigne JY, Tamalet B. Standardized radiologic protocol for the study of common coccygodynia and characteristics of the lesions observed in the sitting position. Clinical elements differentiating luxation, hypermobility, and normal mobility. Spine. 1996 Nov 15:21(22):2588-93 [PubMed PMID: 8961446]

Foye PM, Kumbar S, Koon C. Improving Coccyx Radiographs in Emergency Departments. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2016 Oct:207(4):W77. doi: 10.2214/AJR.16.16542. Epub 2016 Jul 6 [PubMed PMID: 27383137]

Woon JT, Perumal V, Maigne JY, Stringer MD. CT morphology and morphometry of the normal adult coccyx. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2013 Apr:22(4):863-70. doi: 10.1007/s00586-012-2595-2. Epub 2012 Nov 29 [PubMed PMID: 23192732]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFoye PM, Kumar S. Letter to the editor concerning "CT Morphology and Morphometry of the normal adult coccyx" [by Woon JT et al. (2013); Eur Spine J 22(4):863-870]. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2014 Mar:23(3):701. doi: 10.1007/s00586-013-3118-5. Epub 2013 Nov 30 [PubMed PMID: 24292276]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWoon JT, Maigne JY, Perumal V, Stringer MD. Magnetic resonance imaging morphology and morphometry of the coccyx in coccydynia. Spine. 2013 Nov 1:38(23):E1437-45. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182a45e07. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23917643]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFoye PM, Desai RD. MRI, CT scan, and dynamic radiographs for coccydynia: comment on the article "role for magnetic resonance imaging in coccydynia with sacrococcygeal dislocation", by Trouvin et al., Joint Bone Spine 2013;80:214-16. Joint bone spine. 2014 May:81(3):280. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2013.12.008. Epub 2014 Jan 23 [PubMed PMID: 24462128]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMazzoleni MG, Maffulli N, Bardazzi T, Memminger M, Bertini FA, Migliorini F. Management of coccygodynia: talking points from a systematic review of recent clinical trials. Annals of joint. 2025:10():9. doi: 10.21037/aoj-24-40. Epub 2025 Jan 21 [PubMed PMID: 39981432]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMitra R, Cheung L, Perry P. Efficacy of fluoroscopically guided steroid injections in the management of coccydynia. Pain physician. 2007 Nov:10(6):775-8 [PubMed PMID: 17987101]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNourani B, Norton D, Kuchera W, Rabago D. Transrectal osteopathic manipulation treatment for chronic coccydynia: feasibility, acceptability and patient-oriented outcomes in a quality improvement project. Journal of osteopathic medicine. 2024 Feb 1:124(2):77-83. doi: 10.1515/jom-2023-0001. Epub 2023 Nov 24 [PubMed PMID: 37999720]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFoye PM, Buttaci CJ, Stitik TP, Yonclas PP. Successful injection for coccyx pain. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation. 2006 Sep:85(9):783-4 [PubMed PMID: 16924191]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceElezović N, Stojanović Stipić S, Perković M, Elezović A, Elezović T. COCCYGODYNIA. Acta clinica Croatica. 2023 Nov:62(Suppl4):97-101. doi: 10.20471/acc.2023.62.s4.14. Epub [PubMed PMID: 40463454]

Swain BP, Vidhya S, Kumar S. Ganglion Impar Block: A Magic Bullet to Fix Idiopathic Coccygodynia. Cureus. 2023 Jan:15(1):e33911. doi: 10.7759/cureus.33911. Epub 2023 Jan 18 [PubMed PMID: 36819309]

Foye PM. New approaches to ganglion impar blocks via coccygeal joints. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2007 May-Jun:32(3):269 [PubMed PMID: 17543827]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFoye PM. Ganglion impar blocks for chronic pelvic and coccyx pain. Pain physician. 2007 Nov:10(6):780-1; author reply 781 [PubMed PMID: 17987103]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFoye PM, Patel SI. Paracoccygeal corkscrew approach to ganglion impar injections for tailbone pain. Pain practice : the official journal of World Institute of Pain. 2009 Jul-Aug:9(4):317-21. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2009.00291.x. Epub 2009 May 29 [PubMed PMID: 19500274]

Plancarte R, González-Ortiz JC, Guajardo-Rosas J, Lee A. Ultrasonographic-assisted ganglion impar neurolysis. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2009 Jun:108(6):1995; author reply 1995-6. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181a41531. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19448244]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceScott KM, Fisher LW, Bernstein IH, Bradley MH. The Treatment of Chronic Coccydynia and Postcoccygectomy Pain With Pelvic Floor Physical Therapy. PM & R : the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation. 2017 Apr:9(4):367-376. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2016.08.007. Epub 2016 Aug 24 [PubMed PMID: 27565640]

Wray CC, Easom S, Hoskinson J. Coccydynia. Aetiology and treatment. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 1991 Mar:73(2):335-8 [PubMed PMID: 2005168]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKara D, Pulatkan A, Ucan V, Orujov S, Elmadag M. Traumatic coccydynia patients benefit from coccygectomy more than patients undergoing coccygectomy for non-traumatic causes. Journal of orthopaedic surgery and research. 2023 Oct 27:18(1):802. doi: 10.1186/s13018-023-04098-5. Epub 2023 Oct 27 [PubMed PMID: 37891674]

Pennekamp PH, Kraft CN, Stütz A, Wallny T, Schmitt O, Diedrich O. Coccygectomy for coccygodynia: does pathogenesis matter? The Journal of trauma. 2005 Dec:59(6):1414-9 [PubMed PMID: 16394915]

Perkins R, Schofferman J, Reynolds J. Coccygectomy for severe refractory sacrococcygeal joint pain. Journal of spinal disorders & techniques. 2003 Feb:16(1):100-3 [PubMed PMID: 12571492]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRoa JA, White S, Barthélemy EJ, Jenkins A, Margetis K. Minimally invasive endoscopic approach to perform complete coccygectomy in patients with chronic refractory coccydynia: illustrative case. Journal of neurosurgery. Case lessons. 2022 Jan 17:3(3):. pii: CASE21533. doi: 10.3171/CASE21533. Epub 2022 Jan 17 [PubMed PMID: 36130572]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFoye PM, D'Onofrio GJ. Intraoperative X-rays during coccygectomy. Pediatric surgery international. 2018 Aug:34(8):905. doi: 10.1007/s00383-018-4252-2. Epub 2018 Apr 3 [PubMed PMID: 29616299]