Introduction

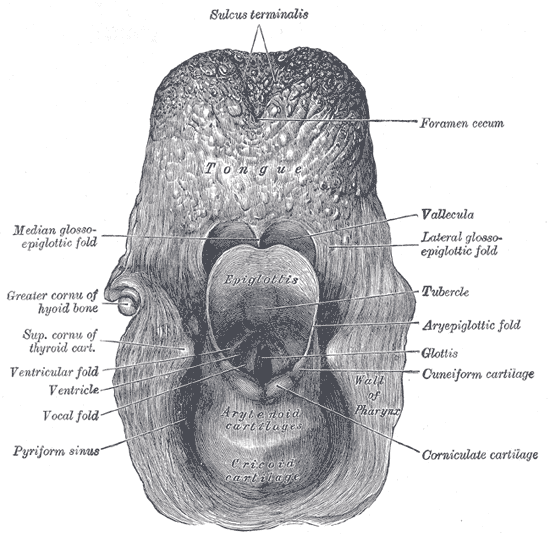

Hypopharyngeal cancer is a rare and aggressive tumor that originates between the oropharynx and the esophageal inlet, inferior to the hyoid bone and superior to the lower margin of the cricoid cartilage. The hypopharynx comprises 3 subsites: the postcricoid space, the pyriform sinuses, and the posterior pharyngeal wall (see Image. The Larynx.). While these structures all lie close to the larynx, hypopharyngeal cancer is anatomically, pathologically, and therapeutically distinct from laryngeal cancer.[1]

Squamous cell carcinoma accounts for 95% of hypopharyngeal cancers, while adenocarcinoma, sarcoma, and nonepidermoid carcinomas account for the majority of the remaining cases.[2] Tumors of the hypopharynx have a propensity for local invasion into the aerodigestive tract and lymphatic spread; 70% of patients present with lymph node metastasis at diagnosis.[1][3] Symptoms at presentation are determined by tumor size and location, with pain, bleeding, and dysphagia being the most common presenting complaints. Patients with more advanced disease may also present with malnutrition, which is a particularly poor prognostic factor. Advanced tumors often invade the larynx, leading to potential airway compromise and aspiration. For this reason, surgical management typically combines partial or total pharyngectomy and laryngectomy, depending on the tumor site and stage at presentation, and can result in significant functional morbidity.[4]

Hypopharyngeal cancer has an annual incidence of approximately 3,000 cases per year in the United States, accounting for about 7% of upper aerodigestive tract cancers. While rarer than laryngeal cancer, hypopharyngeal cancer generally has worse outcomes due to the advanced stage commonly seen at presentation. Prognosis is dictated by stage, with a 60% 5-year survival for patients with early disease (T1-T2), compared to a <25% 5-year survival for those with more advanced tumors (T3-T4) or metastasis to cervical lymph nodes.[5][6]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Hypopharyngeal Cancer Risk Factors

As a primarily squamous cell carcinoma, hypopharyngeal cancer has similar risk factors to other head and neck cancers, which mainly includes the prolonged consumption of alcohol and tobacco products, which act synergistically to enhance each other's carcinogenic potential. As a result, patients with hypopharyngeal cancer are typically males older than 50 with strong histories of alcohol and tobacco use. Other risk factors for hypopharyngeal cancer include:

- Plummer-Vinson syndrome, also known as sideropenic dysphagia. This syndrome, which is primarily seen in premenopausal women, is characterized by iron deficiency anemia, postcricoid dysphagia, and high esophageal mucosal webs. This condition significantly increases the risks of developing postcricoid cancers and is a significant cause of hypopharyngeal cancers in women with iron deficiency anemia who are below the age of 50.[7]

- Asbestos exposure may contribute to the development of hypopharyngeal cancer, although the exact relationship remains unclear. Asbestos exposure is considered an independent risk factor for many malignancies.[8]

- Recurrent irritation from gastric content reflux is recognized to contribute to tumor formation in the postcricoid region, with a progression from metaplasia to dysplasia similar to that seen in Barrett's esophagus and esophageal carcinoma.[9]

- Chewing of the areca nut (also known as the betel nut), popular in South Asia, Southeast Asia, and East Africa, is strongly associated with hypopharyngeal, oropharyngeal, oral, and esophageal malignancies.[10]

- Human papillomavirus infection is not thought to be a significant risk factor for hypopharyngeal cancer, in contrast to its causative role in cancers of the oral cavity and oropharynx.[11]

Epidemiology

Hypopharyngeal cancers are comparatively uncommon, accounting for about 80,000 new cases or 0.4% of all new cancers worldwide, around 35,000 annual cancer-related deaths, and 0.4% of all cancer-related mortality.[12] The global incidence of hypopharyngeal cancer is 0.8 per 100,000 (0.3 in women and 1.4 in men).[13] Incidence of hypopharyngeal cancer varies by region, with the highest incidence in South-Central Asia, followed by Central and Eastern Europe, Western Europe, and then North America.[12]

Hypopharyngeal cancer comprises 17.3% of head and neck cancers in South-Central Asia, compared to 7.1% in North America, 11.3% to 12.8% across Europe, and 7.3% in Latin America.[14][13] In the United States, around 2,500 hypopharyngeal cancers are diagnosed each year, which make up 3-5% of head and neck cancers.[15][3] This variation in international prevalence is most likely a result of differing social practices regarding the consumption of alcohol and tobacco and the chewing of carcinogenic substances.

Pathophysiology

The vast majority (95%) of hypopharyngeal cancer is squamous cell carcinoma, two-thirds of which is the keratinizing variant.[2] Other tumor types encountered in the hypopharynx include lymphoma, sarcoma, and adenocarcinoma.

Hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma is almost always poorly differentiated and aggressive and often exhibits significant submucosal extension (see Image. Superficial Spread of Hypopharyngeal Cancer). An estimated 5% of hypopharyngeal tumors develop in the postcricoid region, with about 25% originating on the posterior pharyngeal wall and the remaining 70% occurring in the pyriform sinus.[16][17] The precise location within the pyriform sinus dictates the pattern of spread. Tumors originating on the medial wall of the pyriform sinus typically spread along the mucosa, invading the larynx via the paraglottic gutter. In contrast, lateral wall and apex tumors tend to invade the thyroid cartilage directly.[18]

History and Physical

Clinical History

The anatomy of the hypopharynx permits insidious growth such that an enlarging lesion may not be appreciated until it has reached a considerable size. For this reason, hypopharyngeal cancer tends to be more advanced at the time of diagnosis than tumors whose presence is apparent at an earlier juncture. The first symptoms patients experience are often nonspecific, including globus sensation, odynophagia, and referred otalgia. Nodal metastasis occurs relatively early in the course of the disease, and initial presentation is often with a new neck mass. As many as 70% of patients with primary pyriform sinus tumors present with cervical lymph node metastases.[19] As the disease advances, the patient may experience progressive dysphagia, and dysphonia may develop as the tumor invades the larynx or causes vocal cord immobility through cartilage or neural involvement.[3]

Physical Examination

The physical examination for all suspected head and neck cancers must be thorough and methodical. Inspection of the oral cavity, while not able to visualize a primary hypopharyngeal tumor, is vital to rule out a synchronous oral mucosal or oropharyngeal malignancy. Close inspection of the oropharynx may reveal tonsil pillar asymmetry secondary to palatopharyngeus muscle invasion. Advanced tumors may cause pooling of secretions, which may also be observed with a thorough oral cavity evaluation.

Examination of the neck is essential, given the high rates of early nodal metastasis with hypopharyngeal cancer.[20] Particular attention should be paid to cervical lymph node levels 3 and 4 and the supraclavicular region. The laryngeal rocking maneuver can assess for loss of physiologic crepitus, which may indicate an advanced postcricoid lesion or prevertebral tissue invasion. Cranial nerve examination should not be overlooked, as it may reveal findings consistent with glossopharyngeal or vagus nerve invasion, eg, a decreased gag reflex or asymmetric soft palate elevation. The general appearance of the patient also ought to be noted, as cachexia may suggest an advanced lesion or distant metastasis.

Endoscopic evaluation of the hypopharynx and larynx is a critical examination component, providing visualization of pyriform sinus, posterior pharyngeal, or postcricoid tumors (see Image. Postcricoid Hypopharyngeal Cancer). The examiner should look closely for any ulcerated or erythematous mucosal lesions, hyperkeratosis, and vocal cord weakness. Noting any pooling of secretions or laryngeal asymmetry, which may indicate neural invasion by the tumor, is essential.

Evaluation

After a thorough clinical assessment has been performed, the most critical elements of the evaluation for hypopharyngeal cancer are imaging and biopsy. The diagnosis of hypopharyngeal cancer can only be confirmed by pathology; imaging provides essential information for treatment planning and staging, including the following modalities:

- Computerized tomography: Computerized tomography (CT) is a rapid and effective means of assessing tumor location, extent, spread, and nodal involvement (see Image. CT Neck with Contrast.). A contrast-enhanced CT scan of the neck, chest, and abdomen can be used for staging and identifying locoregional spread and distant metastases.

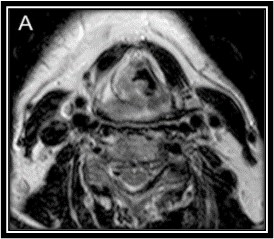

- Magnetic resonance imaging: Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium contrast detects and delineates soft tissue extension and submucosal spread (see Image. MRI Demonstrating Hypopharyngeal Cancer). An MRI scan of the oral cavity and neck provides a very detailed appraisal of the extent of the local spread of the disease. Increased T2 and decreased T1 signal intensity in the larynx has high sensitivity for thyroid cartilage invasion.[21]

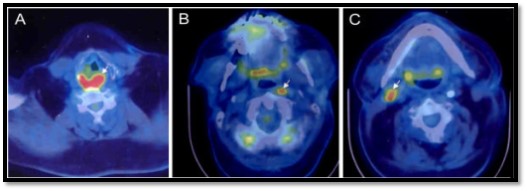

- Positron emission tomography: Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning helps detect distant metastatic spread not identified on CT. Often combined with CT, PET is useful for detecting distant occult metastases or localizing a cancer of unknown primary presenting as a neck mass (see Image. Unknown Primary Cancer Detection).

- Swallowing studies: Barium or water-soluble contrast swallow testing may help detect postcricoid tumors that are not apparent on the endoscopic examination. Swallowing studies can also detect filling defects in the pyriform sinuses due to mucosal lesions.

- Chest x-ray: Chest x-ray is an inexpensive study often performed to identify underlying pulmonary or cardiac disease preoperatively and to screen for lung metastases or synchronous primary pulmonary malignancy.[18]

Panendoscopy, also referred to as triple endoscopy, allows for direct visualization of the upper aerodigestive tract and biopsy of the primary lesion under general anesthesia (see Image. Direct Laryngoscopy View of Hypopharyngeal Cancer). Panendoscopy is also helpful for detecting synchronous tumors, which occur in 10% to 15% of patients.[2] For patients with pathological lymphadenopathy (neck mass) but no primary tumor visible on physical examination, fine needle aspiration may be performed in the office to provide a cytologic diagnosis. Needle biopsy may also be used as a precursor to panendoscopy if the results are concerning but inconclusive.

Routine bloodwork is important to determine the patient's overall health as well as fitness for surgery and systemic therapy. A complete blood count will reveal normocytic or microcytic anemia from occult blood loss or chronic disease or macrocytic anemia secondary to heavy alcohol use. A renal panel may be warranted to assess the potential tolerance of chemotherapy. Liver enzyme evaluation may identify underlying alcoholic cirrhosis or liver metastases, and serum albumin and prealbumin will help to determine the patient's overall nutritional status, which is a significant prognostic factor for healing after surgery and tolerance of chemotherapy.

Treatment / Management

An interprofessional team of head and neck surgeons, medical and radiation oncologists, dieticians, speech therapists, and case managers is necessary to provide standard-of-care treatment.[22] Each patient should be presented at an interprofessional tumor board, which may also include radiology, nuclear medicine, and pathology services members. The overall treatment goal is to achieve locoregional control while minimizing functional morbidity by preserving phonation, deglutition, and oronasal respiratory function. Treatment options include surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or a combination of these.[23][24] According to the following National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2025 guidelines, the treatment approach is dictated by disease stage at presentation:

-

T1, N0 and T2, N0 lesions amenable to larynx-preserving surgery: Options include primary radiation therapy (XRT), or partial laryngopharyngectomy with ipsilateral or bilateral selective neck dissection (SND) ± hemi/total thyroidectomy. Patients who undergo primary surgery and are found to have a single positive lymph node should be considered for postoperative adjuvant XRT. Patients with extranodal extension (ENE) should be given concurrent chemoradiotherapy, while patients with positive margins after surgery should be provided reresection, XRT, or chemoradiotherapy. Patients with close margins, perineural invasion, or lymphovascular invasion should receive postoperative XRT or chemoradiotherapy.

-

T1, N+ and T2-3, N0-3 tumors: Treatment options include primary chemoradiotherapy, or induction chemotherapy with subsequent response assessment, or partial/total laryngopharyngectomy with ipsilateral or bilateral selective neck dissection (if N0) or modified radical neck dissection (MRND) if cervical lymph node metastasis is present, with or without hemi/total thyroidectomy. If a single lymph node metastasis is identified on histopathologic examination of the specimen but no other adverse features are present, postoperative XRT should be considered. If there is ENE or the margins are positive, chemoradiotherapy is recommended, and either XRT alone or chemoradiotherapy is provided if only close margins, perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, or multiple lymph node involvement is encountered.

-

T4a tumors: Therapeutic options include primary chemoradiotherapy, induction chemotherapy with subsequent response assessment, or total laryngopharyngectomy with ipsilateral or bilateral SND/MRND with or without hemi/total thyroidectomy. If ENE or positive margins are identified postoperatively, chemoradiotherapy should be provided. If only close margins, perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, or multiple lymph node involvement are identified, postoperative XRT or chemoradiotherapy are given.

-

T4b, N0-3 lesions: Treatment options include concurrent chemoradiotherapy or induction chemotherapy followed by XRT or chemoradiotherapy. For patients unable to tolerate aggressive measures, palliative XRT or single-agent chemotherapy may be offered.

-

M1 lesions: Chemotherapy remains the primary treatment option, although surgical resection or radiation therapy may be considered when distant metastases are minimal. For those who cannot undergo chemotherapy, palliative surgery or radiation therapy should be explored.

After induction chemotherapy, a complete response at the primary tumor with no worsening of the cervical lymphadenopathy may be followed with either definitive XRT or chemoradiotherapy. A partial response with no further deterioration of neck disease should receive chemoradiotherapy or surgery. If no concerning features are found postoperatively, XRT should be provided. If ENE or positive margins are present, chemoradiotherapy should follow; however, if only close margins, perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, or multiple lymph node involvement is present, either XRT or chemoradiotherapy is provided.

If the primary tumor fails to respond or the neck disease worsens, surgery may be offered for a partial response unless the nodal disease is unresectable. In that case, options include concurrent chemoradiotherapy or induction chemotherapy followed by XRT if no distant metastases are present. If distant metastases are present, chemotherapy is the mainstay of treatment, although surgical resection or XRT may be offered if the metastases are limited. For patients unable to tolerate aggressive measures, palliation with surgery, XRT, or single-agent chemotherapy may be offered. Induction chemotherapy followed by definitive radiation therapy has similar survival outcomes compared to primary surgery.[25]

Should disease recur or persist locoregionally after treatment is complete, surgery with or without postoperative XRT or chemoradiation may be offered if the cancer is deemed resectable. For unresectable disease, the patient may opt for XRT, chemotherapy, or chemoradiation. For patients who have distant metastases after completion of treatment, a combination of XRT, chemotherapy, and surgery may be provided with curative intent if metastases are limited or for palliation if not. Of note, while typically only considered for unresectable, persistent, or recurrent disease, clinical trials may be viable options for patients with hypopharyngeal cancer at any stage.

Surgical Management

With respect to surgical options, the approach employed depends upon the location and extent of the tumor. Options for pyriform sinus tumors are determined by their specific anatomy. Early tumors of the lateral wall of the pyriform sinus are amenable to partial pharyngectomy with partial resection of the lateral thyroid cartilage, usually the superior portion of the ala. Lesions of the medial wall of the pyriform sinus are also potentially suitable for partial laryngopharyngectomy. Tumors extending into the pyriform apex, posterior pharyngeal wall, or post-cricoid space typically require total laryngopharyngectomy.[26][27][28](A1)

Tumors in the postcricoid region tend to be more challenging to detect clinically, present later than other hypopharyngeal cancers, and are often more advanced at the time of treatment. They, therefore, typically require more extensive resection, reconstruction, and adjuvant therapy. Laryngopharyngectomy is usually required due to significant submucosal extension and limited surgical exposure. Partial esophagectomy may be required if esophageal invasion is present. Given the substantial morbidity of these more extensive operations, the patient’s fitness for surgery must be carefully considered, particularly in cases where a free flap may be required to repair the defect. Radial forearm-free flaps are often used to repair a partial esophagectomy defect.[22]

The extent of local invasion dictates posterior pharyngeal wall tumor management. Superficial mucosal lesions may be amenable to wide local excision with primary closure. Lesions with more extensive spread and prevertebral tissue invasion may not be suitable for surgical management, as it may be impossible to achieve clear margins with a pharyngectomy in these cases. The type of reconstruction required also significantly impacts outcomes; intuitively, morbidity and in-hospital mortality are proportional to the extent of the tissue resection. Laryngopharyngectomy patients requiring a radial forearm or anterolateral thigh free flap have considerably lower mortality than jejunal graft recipients. Patients who undergo gastric pull-ups to reconstruct larger esophageal defects have a worse prognosis, with an in-hospital mortality rate of around 11%.[29]

Transoral laser microsurgery (TLM) and transoral robotic surgery (TORS) can be options for T1, T2, and select T3 lesions.[23][30] Transoral laser microsurgery for T1 to T2 tumors produces outcomes comparable to those of radiation and open surgery, with the potential for less morbidity and improved functional outcomes, although data are limited, and the role of TORS for more advanced hypopharyngeal tumors remains to be determined.[31][32] Limitations to TLM include the potential for a limited line of sight with a lack of 3-dimensional appreciation of the lesion, the need for piecemeal resection of larger lesions, and the potential difficulty accurately identifying tumor margins due to tissue alteration by the CO2 laser.

TORS has the potential to overcome some of the disadvantages of TLM while also achieving comparable oncologic outcomes to other modalities and minimizing morbidity. Exclusion criteria for TORS include cases with an inadequate view due to retrognathia or trismus, thyroid cartilage or prevertebral fascia involvement, or unresectable nodal disease (eg, carotid artery invasion).[33] Minimally invasive approaches, such as TLM and TORS, also have disadvantages. Not only do they require costly equipment, but they take much longer to set up than open surgery, require learning an entirely new set of techniques, and significantly limit surgical site exposure if emergency access is needed, as in the case of an expanding hematoma, for example.

Given the high rate of occult nodal metastasis of hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma, a prophylactic level 2 to 4 SND that may include pre- and paratracheal lymph nodes and a hemithyroidectomy is recommended for patients with no clinical evidence of cervical lymphadenopathy (N0 neck) who undergo primary surgery. A comprehensive level 1 to 5 MRND with or without pre/paratracheal lymph node dissection and hemi- or total thyroidectomy is warranted for node-positive patients.[34][35] Data on the treatment of the N0 contralateral neck are limited, although some evidence supports the need for contralateral neck dissection for medial pyriform wall tumors.[36]

Radiotherapeutic Management

Radiation therapy may be employed as a primary definitive treatment by itself, combined with chemotherapy, used as a salvage option, or provided as an adjuvant after surgery when close margins, perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, or multiple lymph node involvement is encountered. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), or variants thereof, eg, helical tomotherapy and volumetric modulated arc therapy, is the preferred means of delivering radiation because it spares the salivary glands, temporal lobes, cochleae, auditory nerves, and optic nerves.

Irradiating cervical lymph node levels II to IV and the lateral retropharyngeal nodes bilaterally are recommended for all hypopharyngeal tumors. The inclusion of level 5 adds minimal further risk of complications or adverse effects, and level 6 should be added as well under the following conditions: involvement of the pyriform sinus apex, advanced T stage, primary tumor located in the postcricoid region, and presence of cervical nodal involvement. For definitive XRT, 66 to 82 Gy are administered over 6 to 7 weeks, depending upon the fractionation schedule, but typically with no more than 2 Gy per day. For adjuvant therapy, the dose is somewhat smaller, at 44 to 63 Gy; however, if positive margins or ENE are identified, the dose is increased to 60 to 66 Gy. When combined with chemotherapy, 70 Gy is given for primary treatment and 44 to 63 Gy for adjuvant therapy. Ideally, XRT should be provided within 6 weeks after surgery.

Chemotherapy and Chemoradiation Management

Chemoradiation may be performed as primary therapy for advanced tumors with the intent of laryngeal conservation, as postoperative adjuvant therapy, or in a palliative setting for unresectable tumors. The concurrent administration of chemotherapeutic agents sensitizes head and neck cancers to radiation, thus improving treatment efficacy and survival compared to radiation alone. Cisplatin is often the systemic therapy of choice and is routinely combined with 5-fluorouracil.[37][38] As with other head and neck squamous cell carcinomas, postoperative chemotherapy with radiation is recommended for extranodal extension and/or positive or close mucosal margins. Definitive chemoradiation is an organ preservation strategy that has similar survival outcomes to primary surgery for patients with hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma.[25] Salvage laryngopharyngectomy is typically performed in cases where primary chemoradiation fails.[39] (A1)

Systemic chemotherapy, when administered without concurrent XRT, is generally provided as either induction therapy or as an option for patients with recurrent, unresectable, or metastatic disease. A regimen of docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil is preferred for induction therapy, although paclitaxel may be substituted for docetaxel. Cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil may be combined with immunotherapy, such as the PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab, for patients with recurrent, unresectable, or metastatic disease. If pembrolizumab fails, nivolumab, another PD-1 inhibitor, may used as second-line treatment.[40][41] Outcomes specific to hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma are comparable to those for PD-1 inhibitors in the broader context of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.[42]

Although data demonstrate improved overall survival with either adjuvant pembrolizumab or nivolumab compared to standard single-agent chemotherapy, salvage surgery results in an improved prognosis compared to immunotherapy alone in cases of recurrent or residual hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma.[43][44] The role of adjuvant immunotherapy in the setting of salvage surgery is currently being investigated in clinical trials.[39] Moreover, data to support the combination of PD-1 inhibitors with paclitaxel and cisplatin as a feasible laryngeal preservation strategy for primary treatment of locally advanced hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma have been documented.[45](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

Presenting symptoms of hypopharyngeal cancer can be vague and seemingly innocuous, such as globus sensation or dysphagia, giving rise to a broad differential diagnosis that includes benign conditions like reflux, cricopharyngeal bar, and esophageal dysmotility. When a patient presents with these symptoms, a thorough physical examination and routine flexible laryngopharyngoscopy are critical to rule out a malignant process.

Many patients with hypopharyngeal cancer will initially present with a new neck mass, which also has a broad differential diagnosis. While pediatric neck masses are typically due to infection or, less commonly, congenital anomalies, a neck mass in an adult should always be presumed to represent a malignant process until proven otherwise. The differential diagnosis for a new neck mass in an adult includes metastasis from other head and neck subsites (eg, the oral cavity, oropharynx, nasopharynx and larynx), metastatic thyroid cancer, a metastatic cutaneous malignancy, and lymphoma. More benign considerations include infectious processes like mononucleosis from Epstein-Barr virus or cytomegalovirus, cat scratch disease, toxoplasmosis or tuberculosis, an inflammatory autoimmune process (eg, sarcoidosis), a benign neoplasm (eg, a lipoma), or acute infection of a previously unrecognized congenital lesion (eg, a branchial cleft cyst). Thorough examination, flexible laryngopharyngoscopy, ultrasonography, fine needle aspiration, cross-sectional imaging, and panendoscopy are all valuable methods of determining an accurate diagnosis.

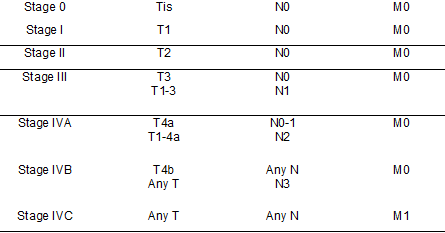

Staging

Tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging, developed by the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), is the standard system used to describe the progression of hypopharyngeal cancer. The latest version is the 8th edition, released in 2018 (see Image. Hypopharyngeal Cancer Staging).[46]

According to the AJCC UICC TNM 8th edition, hypopharyngeal cancers are assigned a clinical stage as follows:

Extent of the primary tumor (T)

- TX: Primary tumor cannot be assessed

- Tis: Carcinoma in situ

- T1: Tumor limited to 1 subsite (pyriform sinus, posterior pharyngeal wall, post-cricoid region) of the hypopharynx and/or 2 cm or less in greatest dimension

- T2: Tumor invades >1 subsite of the hypopharynx or an adjacent site or measures >2 cm but not >4 cm in greatest dimension without causing impairment of vocal cord mobility

- T3: Tumor >4 cm in greatest dimension, or with extension into the esophageal mucosa or impairment of vocal cord mobility

- T4

- T4a: Moderately advanced local disease; tumor invades any of the following:

- Thyroid or cricoid cartilage

- Hyoid bone

- Thyroid gland

- Esophagus

- Central cervical compartment soft tissue

- T4b: Very advanced local disease: tumor invades prevertebral fascia, encases carotid artery, or invades mediastinum

- T4a: Moderately advanced local disease; tumor invades any of the following:

Cervical lymph node involvement (N)

- NX: Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed

- N0: No regional lymph node metastasis

- N1: Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node ≤3 cm in greatest dimension and without ENE

- N2

- N2a: Single ipsilateral lymph node ≤3 cm and ENE+ or single ipsilateral lymph node >3 cm but ≤6 cm in greatest dimension and ENE negative

- N2b: Metastases in multiple ipsilateral lymph nodes, none >6 cm in greatest dimension and ENE negative

- N2c: Metastases in bilateral or contralateral lymph node(s), none >6 cm in greatest dimension and ENE negative

- N3

- N3a: Metastasis in a lymph node that is >6 cm in greatest dimension and ENE negative

- N3b: Metastasis in any of the following:

- Single ipsilateral lymph node, >3 cm with ENE

- Multiple ipsilateral, contralateral, or bilateral lymph nodes, any with ENE

- Single contralateral lymph node of any size and ENE

Extent of distant metastases (M)

- M0: No distant metastasis

- M1: Distant metastasis

Prognosis

Hypopharyngeal cancer has a poorer prognosis than other head and neck cancers owing to its typically advanced presentation and early nodal metastasis. While patients who present with early-stage lesions and no nodal metastases can expect a 5-year survival of up to 70%, late presentation is the norm, and therefore, the overall 5-year survival rate for hypopharyngeal cancer is as low as 20%.

Cervical nodal metastasis is common in hypopharyngeal cancer, contributing to poorer prognosis. The proportion of nodal disease at presentation by tumor stage is as follows:

- T1: 60%

- T2: 65% to 70%

- T3: 84%

- T4: 85%

The 5-year survival based on overall stage is 63% for stage I, 57.5% for stage II, 42% for stage III, and 22% for stage IV.[2] Tumors of the postcricoid region and pyriform apex have worse survival rates than lesions involving the lateral wall of the pyriform sinus or the aryepiglottic fold. Tumor volume and radiologic cross-sectional area are proportional to poor outcomes.[47] Extranodal extension, lymphovascular invasion, T3 to T4 tumors, and involvement of lower lymph nodes are associated with lower recurrence-free survival rates.[25] Lymphovascular invasion portends a particularly poor prognosis, with an adverse impact on 5-year overall survival and recurrence-free survival.[48]

Complications

Morbidity from the treatment of hypopharyngeal cancer can be substantial.

Surgical Complications

Intraoperative and immediate postoperative complications include hemorrhage, spinal accessory nerve injury, hypoglossal nerve injury, vagus nerve injury, and phrenic nerve injury. Hypocalcemia secondary to parathyroid gland explantation, revascularization, or injury is a risk if concomitant thyroidectomy is performed. Failure of free flap reconstruction can occur due to venous or arterial thrombosis, which may lead to additional sequelae. Pharyngocutaneous fistula is the most common risk, especially in more extensive resections, salvage surgery, or postoperative radiotherapy. Carotid artery blowout is a reported risk in the setting of salvage surgery as well.[39]

Depending on the extent of surgery, patients may suffer from long-term dysphagia, and aspiration pneumonia is a risk if the larynx is spared. Other long-term complications include pharyngeal stenosis requiring dilatation procedures and late fistula formation.[2]

Radiotherapy Complications

With the advent of targeted IMRT, adverse effects of radiation have decreased in severity but can still be severe. Mucositis is a common complication that can cause significant pain and compromise salivary function, resulting in xerostomia, dysgeusia, and dermatitis.[49] Patients often require preoperative gastrostomy tube placement to avoid malnutrition and to lower the risk of aspiration. Late radiotherapy complications include stricture formation, long-term dysphagia, spinal cord lesions, brachial plexus injuries, and osteoradionecrosis of the mandible or vertebral bodies.

Chemotherapy Complications

The complications of chemotherapy can be severe and life-threatening. Myelosuppression and concurrent immunosuppression from systemic therapy increase the risk of neutropenic sepsis. Other complications include alopecia, peripheral neuropathy, severe lethargy, fatigue, nausea, and vomiting. Inadvertent extravasation of chemotherapeutic agents during infusion can be excruciating and limb-threatening. Chemotherapy can also prolong and potentiate the acute complications of radiotherapy, such as mucositis.[50]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Hypopharyngeal cancer is strongly associated with heavy consumption of alcohol and tobacco in both chewed and smoked forms. Public health programs that increase awareness of the dangers of alcohol and tobacco consumption in developed countries may contribute to their lower incidences of hypopharyngeal cancer relative to those of developing countries.[51] Campaigns to reduce the consumption of areca nuts in South Asia, Southeast Asia, and East Africa have been shown to reduce head and neck cancer incidence, including hypopharyngeal cancer.[52]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective management of hypopharyngeal cancer requires a collaborative, interprofessional approach to ensure timely diagnosis, appropriate treatment, and comprehensive patient support. Physicians and advanced practitioners play a critical role in recognizing early symptoms such as dysphagia, odynophagia, or globus sensation and referring patients for further evaluation. Otolaryngologists must perform flexible laryngopharyngoscopy to rule out malignancy, while radiologists and pathologists contribute to accurate diagnosis and staging. Once a diagnosis is confirmed, oncologists develop individualized treatment plans incorporating surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy, with input from multiple specialists to balance therapeutic efficacy with quality-of-life considerations. Coordinated decision-making among all team members ensures a streamlined, evidence-based approach to care.

Beyond diagnosis and treatment, patient-centered care for hypopharyngeal cancer extends to rehabilitation and long-term management. Nurses, clinical nurse specialists, and pharmacists provide essential support, ensuring patients adhere to treatment regimens while managing side effects and complications. Speech and language pathologists, along with physiotherapists, assist in restoring phonation and swallowing function, mitigating the impact of therapy on daily life. Strong interprofessional communication is vital to coordinating these efforts, reducing delays, and enhancing patient safety. Regular follow-ups by the interprofessional team help monitor for recurrence, address treatment-related morbidity, and provide ongoing psychosocial support, ultimately improving patient outcomes and optimizing long-term well-being.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

MRI Demonstrating Hypopharyngeal Cancer. T2 MRI demonstrating hypopharyngeal cancer involving the right pyriform sinus and posterior pharyngeal wall.

Gődény M. Prognostic factors in advanced pharyngeal and oral cavity cancer; significance of multimodality imaging in terms of 7th edition of TNM. Cancer Imaging. 2014;14(1):15. doi: 10.1186/1470-7330-14-15.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Unknown Primary Cancer Detection. PET/CT to detect unknown primary demonstrating (A) hypopharyngeal cancer involving the posterior pharyngeal wall and (B and C) metastatic lymph nodes.

Gődény M. Prognostic factors in advanced pharyngeal and oral cavity cancer; significance of multimodality imaging in terms of 7th edition of TNM. Cancer Imaging. 2014;14(1):15. doi: 10.1186/1470-7330-14-15.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

The Larynx. The entrance to the larynx. The tongue and epiglottis are seen in the posterior view.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Kwon DI, Miles BA, Education Committee of the American Head and Neck Society (AHNS). Hypopharyngeal carcinoma: Do you know your guidelines? Head & neck. 2019 Mar:41(3):569-576. doi: 10.1002/hed.24752. Epub 2018 Dec 20 [PubMed PMID: 30570183]

Hoffman HT, Karnell LH, Shah JP, Ariyan S, Brown GS, Fee WE, Glass AG, Goepfert H, Ossoff RH, Fremgen AM. Hypopharyngeal cancer patient care evaluation. The Laryngoscope. 1997 Aug:107(8):1005-17 [PubMed PMID: 9260999]

Hall SF, Groome PA, Irish J, O'Sullivan B. The natural history of patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the hypopharynx. The Laryngoscope. 2008 Aug:118(8):1362-71. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e318173dc4a. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18496152]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePracy P, Loughran S, Good J, Parmar S, Goranova R. Hypopharyngeal cancer: United Kingdom National Multidisciplinary Guidelines. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 2016 May:130(S2):S104-S110 [PubMed PMID: 27841124]

Kuo P, Chen MM, Decker RH, Yarbrough WG, Judson BL. Hypopharyngeal cancer incidence, treatment, and survival: temporal trends in the United States. The Laryngoscope. 2014 Sep:124(9):2064-9 [PubMed PMID: 25295351]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSimard EP, Torre LA, Jemal A. International trends in head and neck cancer incidence rates: differences by country, sex and anatomic site. Oral oncology. 2014 May:50(5):387-403. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.01.016. Epub 2014 Feb 13 [PubMed PMID: 24530208]

Bakshi SS. PLUMMER VINSON SYNDROME--is it common in males? Arquivos de gastroenterologia. 2015 Jul-Sep:52(3):250-2. doi: 10.1590/S0004-28032015000300018. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26486296]

Marchand JL, Luce D, Leclerc A, Goldberg P, Orlowski E, Bugel I, Brugère J. Laryngeal and hypopharyngeal cancer and occupational exposure to asbestos and man-made vitreous fibers: results of a case-control study. American journal of industrial medicine. 2000 Jun:37(6):581-9 [PubMed PMID: 10797501]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRiley CA, Wu EL, Hsieh MC, Marino MJ, Wu XC, McCoul ED. Association of Gastroesophageal Reflux With Malignancy of the Upper Aerodigestive Tract in Elderly Patients. JAMA otolaryngology-- head & neck surgery. 2018 Feb 1:144(2):140-148. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2017.2561. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29270624]

Secretan B, Straif K, Baan R, Grosse Y, El Ghissassi F, Bouvard V, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Guha N, Freeman C, Galichet L, Cogliano V, WHO International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group. A review of human carcinogens--Part E: tobacco, areca nut, alcohol, coal smoke, and salted fish. The Lancet. Oncology. 2009 Nov:10(11):1033-4 [PubMed PMID: 19891056]

Combes JD, Franceschi S. Role of human papillomavirus in non-oropharyngeal head and neck cancers. Oral oncology. 2014 May:50(5):370-9. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.11.004. Epub 2013 Dec 9 [PubMed PMID: 24331868]

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2018 Nov:68(6):394-424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. Epub 2018 Sep 12 [PubMed PMID: 30207593]

Shield KD, Ferlay J, Jemal A, Sankaranarayanan R, Chaturvedi AK, Bray F, Soerjomataram I. The global incidence of lip, oral cavity, and pharyngeal cancers by subsite in 2012. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2017 Jan:67(1):51-64. doi: 10.3322/caac.21384. Epub 2016 Oct 19 [PubMed PMID: 28076666]

Perdomo S, Martin Roa G, Brennan P, Forman D, Sierra MS. Head and neck cancer burden and preventive measures in Central and South America. Cancer epidemiology. 2016 Sep:44 Suppl 1():S43-S52. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2016.03.012. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27678322]

PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board. Hypopharyngeal Cancer Treatment (PDQ®): Health Professional Version. PDQ Cancer Information Summaries. 2002:(): [PubMed PMID: 26389199]

Pignon JP, Bourhis J, Domenge C, Designé L. Chemotherapy added to locoregional treatment for head and neck squamous-cell carcinoma: three meta-analyses of updated individual data. MACH-NC Collaborative Group. Meta-Analysis of Chemotherapy on Head and Neck Cancer. Lancet (London, England). 2000 Mar 18:355(9208):949-55 [PubMed PMID: 10768432]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKrstevska V. Early stage squamous cell carcinoma of the pyriform sinus: a review of treatment options. Indian journal of cancer. 2012 Apr-Jun:49(2):236-44. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.102920. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23107977]

Wycliffe ND, Grover RS, Kim PD, Simental A Jr. Hypopharyngeal cancer. Topics in magnetic resonance imaging : TMRI. 2007 Aug:18(4):243-58 [PubMed PMID: 17893590]

Lefebvre JL, Castelain B, De la Torre JC, Delobelle-Deroide A, Vankemmel B. Lymph node invasion in hypopharynx and lateral epilarynx carcinoma: a prognostic factor. Head & neck surgery. 1987 Sep-Oct:10(1):14-8 [PubMed PMID: 3449476]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGarneau JC, Bakst RL, Miles BA. Hypopharyngeal cancer: A state of the art review. Oral oncology. 2018 Nov:86():244-250. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2018.09.025. Epub 2018 Oct 4 [PubMed PMID: 30409307]

Schmalfuss IM. Imaging of the hypopharynx and cervical esophagus. Magnetic resonance imaging clinics of North America. 2002 Aug:10(3):495-509, vi [PubMed PMID: 12530231]

Adelstein D, Gillison ML, Pfister DG, Spencer S, Adkins D, Brizel DM, Burtness B, Busse PM, Caudell JJ, Cmelak AJ, Colevas AD, Eisele DW, Fenton M, Foote RL, Gilbert J, Haddad RI, Hicks WL, Hitchcock YJ, Jimeno A, Leizman D, Lydiatt WM, Maghami E, Mell LK, Mittal BB, Pinto HA, Ridge JA, Rocco J, Rodriguez CP, Shah JP, Weber RS, Witek M, Worden F, Yom SS, Zhen W, Burns JL, Darlow SD. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Head and Neck Cancers, Version 2.2017. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. 2017 Jun:15(6):761-770. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0101. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28596256]

Takes RP, Strojan P, Silver CE, Bradley PJ, Haigentz M Jr, Wolf GT, Shaha AR, Hartl DM, Olofsson J, Langendijk JA, Rinaldo A, Ferlito A, International Head and Neck Scientific Group. Current trends in initial management of hypopharyngeal cancer: the declining use of open surgery. Head & neck. 2012 Feb:34(2):270-81. doi: 10.1002/hed.21613. Epub 2010 Nov 10 [PubMed PMID: 22228621]

Posner M. Evolving strategies for combined-modality therapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer. The oncologist. 2007 Aug:12(8):967-74 [PubMed PMID: 17766656]

Lin H, Wang T, Heng Y, Zhu X, Zhou L, Zhang M, Shi Y, Cao P, Tao L. Risk stratification of postoperative recurrence in hypopharyngeal squamous-cell carcinoma patients with nodal metastasis. Journal of cancer research and clinical oncology. 2021 Mar:147(3):803-811. doi: 10.1007/s00432-020-03337-0. Epub 2020 Jul 29 [PubMed PMID: 32728810]

Forastiere AA, Ismaila N, Lewin JS, Nathan CA, Adelstein DJ, Eisbruch A, Fass G, Fisher SG, Laurie SA, Le QT, O'Malley B, Mendenhall WM, Patel S, Pfister DG, Provenzano AF, Weber R, Weinstein GS, Wolf GT. Use of Larynx-Preservation Strategies in the Treatment of Laryngeal Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2018 Apr 10:36(11):1143-1169. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.7385. Epub 2017 Nov 27 [PubMed PMID: 29172863]

Lefebvre JL, Chevalier D, Luboinski B, Kirkpatrick A, Collette L, Sahmoud T. Larynx preservation in pyriform sinus cancer: preliminary results of a European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer phase III trial. EORTC Head and Neck Cancer Cooperative Group. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1996 Jul 3:88(13):890-9 [PubMed PMID: 8656441]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHolsinger FC, Motamed M, Garcia D, Brasnu D, Ménard M, Laccourreye O. Resection of selected invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the pyriform sinus by means of the lateral pharyngotomy approach: the partial lateral pharyngectomy. Head & neck. 2006 Aug:28(8):705-11 [PubMed PMID: 16786602]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNouraei SA, Dias A, Kanona H, Vokes D, O'Flynn P, Clarke PM, Middleton SE, Darzi A, Aylin P, Jallali N. Impact of the method and success of pharyngeal reconstruction on the outcome of treating laryngeal and hypopharyngeal cancers with pharyngolaryngectomy: A national analysis. Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic surgery : JPRAS. 2017 May:70(5):628-638. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2016.12.009. Epub 2017 Jan 9 [PubMed PMID: 28325565]

Steiner W, Ambrosch P, Hess CF, Kron M. Organ preservation by transoral laser microsurgery in piriform sinus carcinoma. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2001 Jan:124(1):58-67 [PubMed PMID: 11228455]

Casanueva R, López F, García-Cabo P, Álvarez-Marcos C, Llorente JL, Rodrigo JP. Oncological and functional outcomes of transoral laser surgery for hypopharyngeal carcinoma. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2023 Feb:280(2):829-837. doi: 10.1007/s00405-022-07622-1. Epub 2022 Sep 3 [PubMed PMID: 36056169]

Kuo CL, Lee TL, Chu PY. Conservation surgery for hypopharyngeal cancer: changing paradigm from open to endoscopic. Acta oto-laryngologica. 2013 Oct:133(10):1096-103. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2013.805341. Epub 2013 Jul 22 [PubMed PMID: 23869670]

Park YM, Kim WS, De Virgilio A, Lee SY, Seol JH, Kim SH. Transoral robotic surgery for hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: 3-year oncologic and functional analysis. Oral oncology. 2012 Jun:48(6):560-6. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.12.011. Epub 2012 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 22265334]

Shah JP. Patterns of cervical lymph node metastasis from squamous carcinomas of the upper aerodigestive tract. American journal of surgery. 1990 Oct:160(4):405-9 [PubMed PMID: 2221244]

Biau J, Lapeyre M, Troussier I, Budach W, Giralt J, Grau C, Kazmierska J, Langendijk JA, Ozsahin M, O'Sullivan B, Bourhis J, Grégoire V. Selection of lymph node target volumes for definitive head and neck radiation therapy: a 2019 Update. Radiotherapy and oncology : journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 2019 May:134():1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2019.01.018. Epub 2019 Jan 30 [PubMed PMID: 31005201]

Johnson JT, Bacon GW, Myers EN, Wagner RL. Medial vs lateral wall pyriform sinus carcinoma: implications for management of regional lymphatics. Head & neck. 1994 Sep-Oct:16(5):401-5 [PubMed PMID: 7960736]

Bourhis J, Guigay J, Temam S, Pignon JP. Chemo-radiotherapy in head and neck cancer. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. 2006 Sep:17 Suppl 10():x39-41 [PubMed PMID: 17018748]

Vermorken JB, Remenar E, van Herpen C, Gorlia T, Mesia R, Degardin M, Stewart JS, Jelic S, Betka J, Preiss JH, van den Weyngaert D, Awada A, Cupissol D, Kienzer HR, Rey A, Desaunois I, Bernier J, Lefebvre JL, EORTC 24971/TAX 323 Study Group. Cisplatin, fluorouracil, and docetaxel in unresectable head and neck cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2007 Oct 25:357(17):1695-704 [PubMed PMID: 17960012]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCooke PV, Wu MP, Rathi VK, Chen S, Kappauf C, Roof SA, Lin DT, Deschler DG. Salvage surgery for recurrent or residual hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: A systematic review. Head & neck. 2024 Nov:46(11):2725-2736. doi: 10.1002/hed.27794. Epub 2024 May 8 [PubMed PMID: 38716810]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHarrington KJ, Burtness B, Greil R, Soulières D, Tahara M, de Castro G Jr, Psyrri A, Brana I, Basté N, Neupane P, Bratland Å, Fuereder T, Hughes BGM, Mesia R, Ngamphaiboon N, Rordorf T, Wan Ishak WZ, Lin J, Gumuscu B, Swaby RF, Rischin D. Pembrolizumab With or Without Chemotherapy in Recurrent or Metastatic Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Updated Results of the Phase III KEYNOTE-048 Study. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2023 Feb 1:41(4):790-802. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.02508. Epub 2022 Oct 11 [PubMed PMID: 36219809]

Oliveira G, Egloff AM, Afeyan AB, Wolff JO, Zeng Z, Chernock RD, Zhou L, Messier C, Lizotte P, Pfaff KL, Stromhaug K, Penter L, Haddad RI, Hanna GJ, Schoenfeld JD, Goguen LA, Annino DJ, Jo V, Oppelt P, Pipkorn P, Jackson R, Puram SV, Paniello RC, Rich JT, Webb J, Zevallos JP, Mansour M, Fu J, Dunn GP, Rodig SJ, Ley J, Morris LGT, Dunn L, Paweletz CP, Kallogjeri D, Piccirillo JF, Adkins DR, Wu CJ, Uppaluri R. Preexisting tumor-resident T cells with cytotoxic potential associate with response to neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 in head and neck cancer. Science immunology. 2023 Sep 8:8(87):eadf4968. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.adf4968. Epub 2023 Sep 8 [PubMed PMID: 37683037]

Fang Q, Li X, Xu P, Cao F, Wu D, Zhang X, Chen C, Gao J, Su Y, Liu X. PD-1 inhibitor combined with paclitaxel and cisplatin in the treatment of recurrent and metastatic hypopharyngeal/laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma: efficacy and survival outcomes. Frontiers in immunology. 2024:15():1353435. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1353435. Epub 2024 May 17 [PubMed PMID: 38827739]

Burtness B, Harrington KJ, Greil R, Soulières D, Tahara M, de Castro G Jr, Psyrri A, Basté N, Neupane P, Bratland Å, Fuereder T, Hughes BGM, Mesía R, Ngamphaiboon N, Rordorf T, Wan Ishak WZ, Hong RL, González Mendoza R, Roy A, Zhang Y, Gumuscu B, Cheng JD, Jin F, Rischin D, KEYNOTE-048 Investigators. Pembrolizumab alone or with chemotherapy versus cetuximab with chemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (KEYNOTE-048): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet (London, England). 2019 Nov 23:394(10212):1915-1928. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32591-7. Epub 2019 Nov 1 [PubMed PMID: 31679945]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKonuthula N, Do OA, Gobillot T, Rodriguez CP, Futran ND, Houlton J, Barber BR. Oncologic outcomes of salvage surgery and immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in recurrent head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: A single-institution retrospective study. Head & neck. 2022 Nov:44(11):2465-2472. doi: 10.1002/hed.27162. Epub 2022 Aug 5 [PubMed PMID: 35930296]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFang Q, Xu P, Cao F, Wu D, Liu X. PD-1 Inhibitors combined with paclitaxel (Albumin-bound) and cisplatin for larynx preservation in locally advanced laryngeal and hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: a retrospective study. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy : CII. 2023 Dec:72(12):4161-4168. doi: 10.1007/s00262-023-03550-z. Epub 2023 Oct 7 [PubMed PMID: 37804437]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceZanoni DK, Patel SG, Shah JP. Changes in the 8th Edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Staging of Head and Neck Cancer: Rationale and Implications. Current oncology reports. 2019 Apr 17:21(6):52. doi: 10.1007/s11912-019-0799-x. Epub 2019 Apr 17 [PubMed PMID: 30997577]

Martin SA, Marks JE, Lee JY, Bauer WC, Ogura JH. Carcinoma of the pyriform sinus: predictors of TNM relapse and survival. Cancer. 1980 Nov 1:46(9):1974-81 [PubMed PMID: 7427903]

Gang G, Xinwei C, LiXiao C, Yu Z, Cheng Z, Pin D. Risk factors of lymphovascular invasion in hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma and its influence on prognosis. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2022 Mar:279(3):1473-1479. doi: 10.1007/s00405-021-06906-2. Epub 2021 Jun 2 [PubMed PMID: 34076727]

Siddiqui F, Movsas B. Management of Radiation Toxicity in Head and Neck Cancers. Seminars in radiation oncology. 2017 Oct:27(4):340-349. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2017.04.008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28865517]

Iglesias Docampo LC, Arrazubi Arrula V, Baste Rotllan N, Carral Maseda A, Cirauqui Cirauqui B, Escobar Y, Lambea Sorrosal JJ, Pastor Borgoñón M, Rueda A, Cruz Hernández JJ. SEOM clinical guidelines for the treatment of head and neck cancer (2017). Clinical & translational oncology : official publication of the Federation of Spanish Oncology Societies and of the National Cancer Institute of Mexico. 2018 Jan:20(1):75-83. doi: 10.1007/s12094-017-1776-1. Epub 2017 Nov 20 [PubMed PMID: 29159792]

Lechner M, Breeze CE, Vaz F, Lund VJ, Kotecha B. Betel nut chewing in high-income countries-lack of awareness and regulation. The Lancet. Oncology. 2019 Feb:20(2):181-183. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30911-2. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30723038]

Petersen PE. Oral cancer prevention and control--the approach of the World Health Organization. Oral oncology. 2009 Apr-May:45(4-5):454-60. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.05.023. Epub 2008 Sep 18 [PubMed PMID: 18804412]