Developmental Disturbances of the Teeth, Anomalies of Shape and Size

Developmental Disturbances of the Teeth, Anomalies of Shape and Size

Introduction

Odontogenesis is a complex, highly regulated biological process influenced by multiple factors. Disruptions can lead to anatomical changes and clinical complications, including altered tooth size, which can result in teeth that appear larger, smaller, or significantly different from their expected form. This activity reviews common anomalies affecting tooth shape and size, particularly microdontia, macrodontia, taurodontism, and fusion.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Microdontia is a rare dental anomaly characterized by teeth that appear smaller than expected. True generalized microdontia, a condition affecting all teeth, often occurs in individuals with systemic syndromes, such as pituitary dwarfism and orofaciodigital or oculomandibulofacial syndrome.[1][2][3] Younger patients who have undergone chemoradiotherapy may also develop microdontia due to disruptions in dental development.[4] True generalized microdontia rarely occurs in individuals without underlying genetic or developmental conditions.

Macrodontia, also known as megalodontia, has an unclear etiology, though both genetic and environmental factors have been implicated.[5][6] Generalized macrodontia, where larger-than-normal teeth appear throughout the dentition, has been associated with conditions such as insulin-resistant diabetes, otodental syndrome, and hypophyseal gigantism.[7] In contrast, isolated macrodontia typically occurs without syndromic associations or underlying systemic pathology.[8]

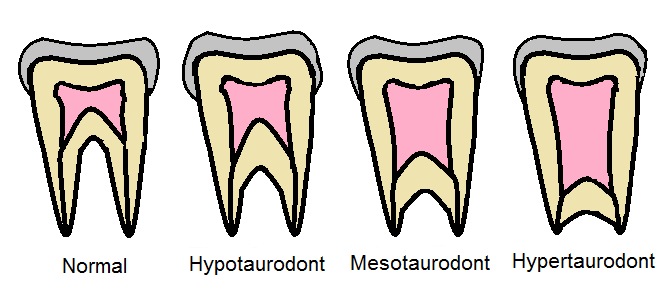

Taurodontism has been commonly attributed to the incomplete invagination of the epithelial root sheath during tooth development, leading to misplaced dentin deposition and an abnormally large pulp chamber (see Image. Dental Taurodontism).[9][10] This anomaly has been associated with several syndromes, including amelogenesis imperfecta, Klinefelter syndrome, and Down syndrome.

Fusion occurs when 2 developing tooth buds join, forming a larger tooth with 2 distinct tooth germs. This process may result from the proximity of adjacent tooth germs or the presence of a developing supernumerary tooth bud near a normally developing tooth.

Epidemiology

Microdontia occurs more frequently in female individuals, with an overall incidence of 1.5% to 2%.[11] The maxillary lateral incisor is most commonly affected, often referred to as a "peg lateral."[12] Macrodontia has no sex predilection and has been reported in permanent teeth, with a prevalence ranging from 0.03% to 1.9%.[13] This condition typically presents in individuals aged 8 to 13, coinciding with the eruption of permanent dentition.

Taurodontism occurs more frequently in male individuals and has been associated with X-linked syndromes.[14] The incidence of this condition is reportedly less than 1%, with a higher prevalence in Arctic and Native American populations.[15] Fusion has been observed in 0.21% of a population of 1,200 patients and has no known sex predilection.[16][17]

Pathophysiology

Microdontia arises from disruptions in normal dental development, where processes fail to progress to completion. These disturbances may have genetic, environmental, or multifactorial origins.

Macrodontia results from the overexpression of developmental signals, leading to hyperactivity in the tissues involved in tooth formation. This anomaly has been linked to systemic, syndromic, and environmental factors and produces teeth that are larger than normal.

Taurodontism has been attributed to 3 proposed pathological mechanisms: an atypical developmental pattern causing delayed calcification of the pulp chamber, a deficiency of odontoblasts causing alterations in the Hertwig epithelial root sheath, or a disruption in developmental homeostasis.[18]

Fusion occurs when 2 developing tooth buds are close enough to merge, forming a single unit. This process may result from the proximity of adjacent tooth buds or the presence of supernumerary teeth. Studies suggest that signaling mediated by the Jagged2 gene may influence tooth development and contribute to fusion.[19] Fusion should be distinguished from gemination, a process in which a single tooth bud attempts to divide, producing a tooth with a partially split crown that appears larger or bifid. In fusion, the total tooth count decreases because 2 teeth merge into 1, whereas in gemination, the overall number of teeth remains unchanged.

Histopathology

Microdontia presents histologically as a structurally normal tooth, but the enamel and dentin layers are thinner and less robust than those of a normal-sized tooth. Macrodontia also appears histologically unremarkable, but the enamel and dentin layers are thicker and more pronounced.

Taurodontism is characterized by a hyperplastic, abnormally large pulp chamber with excess pulpal tissue. Despite the increased volume, the tissue maintains normal histological features.

Teeth affected by fusion appear histologically normal, though the extent and location of fusion influence structural variations. Depending on the developmental stage at which fusion occurs, pulpal chambers, roots, or crowns may be fused or duplicated.[20]

History and Physical

Microdontia often produces teeth with a conical or peg-shaped appearance, most commonly associated with developmental or syndromic conditions. True generalized microdontia, affecting the entire dentition without an underlying syndrome, is rare and warrants further evaluation. Macrodontia presents as teeth that are larger than expected, with generalized cases often linked to syndromic or systemic conditions. A rare variant, polarization, refers to macrodontia affecting premolars, causing them to resemble molars. Only 36 cases have been documented in the literature.[21] Patients with generalized macrodontia should undergo evaluation for potential underlying systemic or syndromic conditions.

Taurodontism is typically diagnosed radiographically during routine dental visits, as patients are usually unaware of the condition.[22] Fusion presents as an enlarged clinical crown resulting from the union of 2 normally separate tooth germs during development (see Image. Dental Fusion in Primary Dentition).

The extent of fusion depends on the stage at which it occurs. Complete fusion arises when the entire tooth develops as a single unit, whereas incomplete fusion results in a fissure or cleft on the tooth surface.

Evaluation

Microdontia refers to teeth that appear smaller than expected, and it is classified based on severity. Localized microdontia affects a single tooth. Relative generalized microdontia occurs when teeth appear smaller due to a disproportionately large maxilla or mandible. True generalized microdontia involves the entire dentition.[23] Macrodontia is often identified on routine dental radiographs between the ages of 8 and 13 when the permanent dentition begins to erupt. Isolated larger-than-normal teeth typically require no intervention, whereas generalized macrodontia should prompt further evaluation for an underlying genetic or developmental condition.[24]

Taurodontism is identified radiographically by enlarged pulp chambers and shortened roots, features that are not clinically observable. Fusion is typically detected during routine dental examinations or when it affects the aesthetic zone, where a single large tooth occupies the space of 2. Patients may remain unaware of the condition unless it presents an aesthetic or functional concern.

Treatment / Management

Microdontia treatment is primarily cosmetic or functional. Patients with abnormally small teeth often present with diastemas between adjacent teeth, which are best managed with orthodontic therapy. In contrast, macrodontia typically requires an interprofessional treatment approach. The decision to retain a macrodont in the dental arch depends on its size and impact on oral anatomy. Exodontia, followed by orthodontic therapy, is the most common treatment strategy.[25](B3)

Taurodont teeth present challenges across multiple dental specialties. The large pulp chamber and prominent pulp horns increase the risk of pulp exposure due to decay. Variability in pulp chamber size and shape, including apically positioned canal orifices and accessory root canal systems, complicates endodontic therapy.[26](B3)

From a prosthodontic perspective, postplacement is highly challenging and often contraindicated due to the unpredictable pulp chamber and the inability to achieve an intimate fit between the post and surrounding tooth structure. Extractions are similarly complicated by the apical positioning of the furcation, which hinders the adaptation of forceps or elevators. However, from a periodontal standpoint, taurodontism may improve the prognosis of affected teeth. The apically positioned root furcation reduces the likelihood of furcation involvement, lowering the risk of periodontal complications.[27](B3)

To minimize further complications, patients should receive counseling on maintaining optimal oral hygiene and caring for these teeth. Dentists may recommend customized oral hygiene strategies based on individual risk factors.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for each anomalous condition is outlined below. Additional diagnostic tools, such as radiographic evaluation and genetic testing, may aid in distinguishing between these conditions.

Microdontia

- Pituitary dwarfism

- Hypopituitarism

- Growth hormone-related defects

Macrodontia

- Gemination

- Fusion

- Facial hemihypertrophy

Taurodontism

- Amelogenesis imperfecta

- Dentinogenesis imperfecta

- X-chromosomal Aneuploidy

Fusion

- Macrodontia

- Gemination

- Talon cusp

Prognosis

Microdontia generally has a good prognosis, as its developmental origin does not necessarily affect dental function. Restorative and orthodontic interventions typically address any functional or aesthetic concerns.[28] Macrodontia also has a favorable prognosis, as dental function usually remains intact. Restorative or orthodontic treatment is often sufficient to manage any associated problems.[29]

Taurodontism typically has a good prognosis if proper oral hygiene is maintained. However, dental interventions may be complicated by an enlarged and unpredictable pulp chamber or pulpal system.[30] Fusion typically has a good prognosis, provided the patient maintains optimal oral hygiene. These teeth are more likely to require restorative, periodontal, or endodontic therapy if not properly maintained.[31]

Complications

Depending on its severity and extent, microdontia may present aesthetic or functional challenges. In most cases, underlying syndromes cause greater difficulties than the dental condition itself.[32]

Macrodontia often presents an aesthetic concern in the anterior maxilla, while macrodonts in the posterior region may contribute to crowding and impede normal tooth eruption. Radiographic monitoring is essential to assess potential eruption abnormalities.

As mentioned, taurodontism presents restorative, prosthodontic, endodontic, and surgical management challenges. Despite these complications, patients are typically unaware of the condition unless dental intervention is required.

Fusion may pose an aesthetic concern due to the altered shape and size of the affected tooth. These teeth are also at an increased risk of decay and periodontal disease and may complicate endodontic therapy.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Microdontia and macrodontia are developmental or genetic in origin and cannot be prevented. Patients concerned about function or aesthetics should consult a licensed dental provider to explore restorative, surgical, or orthodontic treatment options. Fusion is another developmental condition that cannot be prevented. Patients should be counseled on maintaining excellent oral hygiene. If the fused tooth causes functional or aesthetic concerns, evaluation by a licensed dental provider is recommended. In all cases, patients should maintain meticulous oral hygiene, as teeth with developmental disturbances are more susceptible to caries and may require more complex treatment.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Developmental disturbances affecting the shape and size of teeth can significantly alter dental anatomy and necessitate tailored treatment. Some of these conditions primarily present as cosmetic concerns, while others complicate dental care, highlighting the importance of early diagnosis and management.

A collaborative approach among dental professionals enhances patient outcomes. General dentists play a crucial role in early detection, while specialists such as orthodontists, prosthodontists, and endodontists provide more advanced interventions. Coordination with medical professionals is essential when dental anomalies are associated with systemic conditions, ensuring comprehensive, patient-centered care.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Villa A, Albonico A, Villa F. Hypodontia and microdontia: clinical features of a rare syndrome. Journal (Canadian Dental Association). 2011:77():b115 [PubMed PMID: 21846459]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOpinya GN, Kaimenyi JT, Meme JS. Oral findings in Fanconi's anemia. A case report. Journal of periodontology. 1988 Jul:59(7):461-3 [PubMed PMID: 3166059]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBargale SD, Kiran SD. Non-syndromic occurrence of true generalized microdontia with mandibular mesiodens - a rare case. Head & face medicine. 2011 Oct 28:7():19. doi: 10.1186/1746-160X-7-19. Epub 2011 Oct 28 [PubMed PMID: 22035324]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLaverty DP, Thomas MB. The restorative management of microdontia. British dental journal. 2016 Aug 26:221(4):160-6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.595. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27561572]

Küchler EC, Risso PA, Costa Mde C, Modesto A, Vieira AR. Studies of dental anomalies in a large group of school children. Archives of oral biology. 2008 Oct:53(10):941-6. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2008.04.003. Epub 2008 May 19 [PubMed PMID: 18490001]

Acharya S, Kumar Mandal P, Ghosh C. Bilateral molariform mandibular second premolars. Case reports in dentistry. 2015:2015():809463. doi: 10.1155/2015/809463. Epub 2015 Jan 19 [PubMed PMID: 25685564]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePace A, Sandler PJ, Murray A. Macrodont management. Dental update. 2013 Jan-Feb:40(1):18-20, 23-6 [PubMed PMID: 23505854]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDugmore CR. Bilateral macrodontia of mandibular second premolars: a case report. International journal of paediatric dentistry. 2001 Jan:11(1):69-73 [PubMed PMID: 11309876]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWitkop CJ Jr. Manifestations of genetic diseases in the human pulp. Oral surgery, oral medicine, and oral pathology. 1971 Aug:32(2):278-316 [PubMed PMID: 4327157]

Goldstein E, Gottlieb MA. Taurodontism: familial tendencies demonstrated in eleven of fourteen case reports. Oral surgery, oral medicine, and oral pathology. 1973 Jul:36(1):131-44 [PubMed PMID: 4514516]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGuttal KS, Naikmasur VG, Bhargava P, Bathi RJ. Frequency of developmental dental anomalies in the Indian population. European journal of dentistry. 2010 Jul:4(3):263-9 [PubMed PMID: 20613914]

Fekonja A. Prevalence of dental developmental anomalies of permanent teeth in children and their influence on esthetics. Journal of esthetic and restorative dentistry : official publication of the American Academy of Esthetic Dentistry ... [et al.]. 2017 Jul 8:29(4):276-283. doi: 10.1111/jerd.12302. Epub 2017 May 16 [PubMed PMID: 28509361]

Canoglu E, Canoglu H, Aktas A, Cehreli ZC. Isolated bilateral macrodontia of mandibular second premolars: A case report. European journal of dentistry. 2012 Jul:6(3):330-4 [PubMed PMID: 22904663]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBhat SS, Sargod S, Mohammed SV. Taurodontism in deciduous Molars - A Case Report. Journal of the Indian Society of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry. 2004 Oct-Dec:22(4):193-6 [PubMed PMID: 15855716]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMohan RP, Verma S, Agarwal N, Singh U. Taurodontism. BMJ case reports. 2013 Apr 17:2013():. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-008490. Epub 2013 Apr 17 [PubMed PMID: 23598931]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBilge NH, Yeşiltepe S, Törenek Ağırman K, Çağlayan F, Bilge OM. Investigation of prevalence of dental anomalies by using digital panoramic radiographs. Folia morphologica. 2018:77(2):323-328. doi: 10.5603/FM.a2017.0087. Epub 2017 Sep 21 [PubMed PMID: 28933802]

Benediktsdottir IS, Hintze H, Petersen JK, Wenzel A. Accuracy of digital and film panoramic radiographs for assessment of position and morphology of mandibular third molars and prevalence of dental anomalies and pathologies. Dento maxillo facial radiology. 2003 Mar:32(2):109-15 [PubMed PMID: 12775665]

Dineshshankar J, Sivakumar M, Balasubramanium AM, Kesavan G, Karthikeyan M, Prasad VS. Taurodontism. Journal of pharmacy & bioallied sciences. 2014 Jul:6(Suppl 1):S13-5. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.137252. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25210354]

Mitsiadis TA, Regaudiat L, Gridley T. Role of the Notch signalling pathway in tooth morphogenesis. Archives of oral biology. 2005 Feb:50(2):137-40 [PubMed PMID: 15721140]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSultan N. Incidental finding of two rare developmental anomalies: Fusion and dilaceration: A case report and literature review. Journal of natural science, biology, and medicine. 2015 Aug:6(Suppl 1):S163-6. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.166129. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26604610]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceStolbizer F, Cripovich V, Paolini A. Macrodontia associated with growth-hormone therapy: a case report and review of the literature. European journal of paediatric dentistry. 2020 Mar:21(1):53-54. doi: 10.23804/ejpd.2020.21.01.10. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32183529]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePillai KG, Scipio JE, Nayar K, Louis N. Prevalence of taurodontism in premolars among patients at a tertiary care institution in Trinidad. The West Indian medical journal. 2007 Sep:56(4):368-71 [PubMed PMID: 18198744]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChen Y, Zhou F, Peng Y, Chen L, Wang Y. Non-syndromic occurrence of true generalized microdontia with hypodontia: A case report. Medicine. 2019 Jun:98(26):e16283. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000016283. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31261601]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChetty M, Beshtawi K, Roomaney I, Kabbashi S. MACRODONTIA: A brief overview and a case report of KBG syndrome. Radiology case reports. 2021 Jun:16(6):1305-1310. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2021.02.068. Epub 2021 Mar 28 [PubMed PMID: 33854669]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRootkin-Gray VF, Sheehy EC. Macrodontia of a mandibular second premolar: a case report. ASDC journal of dentistry for children. 2001 Sep-Dec:68(5-6):347-9, 302 [PubMed PMID: 11985197]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDurr DP, Campos CA, Ayers CS. Clinical significance of taurodontism. Journal of the American Dental Association (1939). 1980 Mar:100(3):378-81 [PubMed PMID: 6928171]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShifman A, Buchner A. Taurodontism. Report of sixteen cases in Israel. Oral surgery, oral medicine, and oral pathology. 1976 Mar:41(3):400-5 [PubMed PMID: 1061927]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKorkut B, Yanikoglu F, Tagtekin D. Direct Midline Diastema Closure with Composite Layering Technique: A One-Year Follow-Up. Case reports in dentistry. 2016:2016():6810984. doi: 10.1155/2016/6810984. Epub 2016 Jan 6 [PubMed PMID: 26881147]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMangla N, Singh Khinda VI, Kallar S, Singh Brar G. Molarization of mandibular second premolar. International journal of clinical pediatric dentistry. 2014 May:7(2):137-9. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10005-1251. Epub 2014 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 25356014]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMarques-da-Silva B, Baratto-Filho F, Abuabara A, Moura P, Losso EM, Moro A. Multiple taurodontism: the challenge of endodontic treatment. Journal of oral science. 2010 Dec:52(4):653-8 [PubMed PMID: 21206170]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGoh V, Tse OD. Management of Bilateral Mandibular Fused Teeth. Cureus. 2020 Apr 30:12(4):e7899. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7899. Epub 2020 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 32494514]

Ryu YH, Kyun Chae J, Kim JW, Lee S. Lacrimo-auriculo-dento-digital syndrome: A novel mutation in a Korean family and review of literature. Molecular genetics & genomic medicine. 2020 Oct:8(10):e1412. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.1412. Epub 2020 Jul 26 [PubMed PMID: 32715658]