Introduction

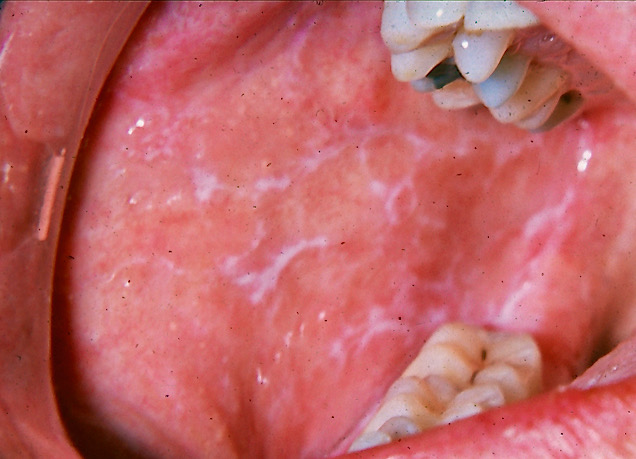

The name "lichen planus" was coined by British dermatologist Erasmus Wilson in 1869.[1] The term "lichen" originates from the Greek word leichen, referring to a moss, while planus is Latin for "flat." Lichen planus comprises a chronic inflammatory disease affecting the skin, hair follicles, nails, and mucosal surfaces, with predominant involvement of the skin and oral mucosa.[2][3] The oral variant, oral lichen planus (OLP), is a chronic condition characterized by periods of relapse and remission, requiring long-term symptomatic treatment and surveillance (see Image. Oral Lichen Planus). Approximately 15% of patients with OLP develop cutaneous lesions, and around 20% develop genital lesions.[4]

Cutaneous involvement is typically self-limiting and presents as violaceous, pruritic papules with overlying reticular white striae (Wickham striae), most commonly affecting the trunk or extremities, including the wrists and ankles.[5] Genital manifestations in women may include erythema, erosions, white reticulated plaques, labial resorption, or scarring.[6] In men, lesions may appear as annular, papulosquamous plaques on the glans penis, occasionally associated with dysuria and dyspareunia.[7]

Esophageal disease occurs in more than 1/4 of patients with OLP. Symptomatic individuals report dysphagia and odynophagia, with endoscopic examination revealing friable mucosa, white plaques, erythema, ulceration, erosions, or stricture formation.[8][9][10]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The precise etiology of lichen planus is unknown. Multiple factors have been implicated in the pathogenesis of this condition, including genetic predisposition, microbial agents, allergies, psychological stress, intestinal disturbances, systemic diseases, and mucosal trauma from sharp teeth. Psychological stress is a significant trigger. Oral lesions frequently worsen during periods of heightened stress or depression, potentially due to elevated oxidative stress markers in oral mucosal cells, saliva, and serum. This increase in oxidative stress may amplify the local immunological response, aggravating existing lesions.

Associations between thyroid dysfunction and OLP have been reported, with elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone and reduced free thyroxine levels observed in affected individuals. These findings suggest that autoimmune thyroid disease may contribute to OLP pathogenesis. Studies have likewise identified a correlation between hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and OLP.

Shifts in the oral microbiota have been associated with the onset of OLP, suggesting an interplay between microbial imbalance and immune dysregulation.[11] Alterations in the gut microbiota may compromise intestinal barrier integrity, permitting translocation of bacteria and their metabolites into the bloodstream, potentially activating T cells, and contributing to OLP pathogenesis.[12][13] Studies examining the oral microbiome in OLP have demonstrated dysbiosis within lesions compared to adjacent mucosa. However, the precise role of these microbial changes remains unclear. Research has also explored the salivary mycobiome, in which fungal imbalance may modulate bacterial communities and host immune responses. Overall, the relationship between microbial shifts and immune dysregulation in OLP requires further investigation.

Hormonal fluctuations, particularly during menopause, appear to influence OLP development. Endocrine alterations, including changes in sex steroid hormone levels, have been observed in affected individuals. Elevated estrogen levels have been correlated with increased lesion severity.[14] The specific contribution of hormonal variations to OLP pathogenesis remains uncertain, underscoring the need for further studies to clarify the complex interaction between hormones and disease expression.

Epidemiology

A 2020 meta-analysis reported that the estimated global prevalence of OLP is approximately 0.89% to 0.98%, with higher rates observed in clinical populations.[15] The condition occurs twice as frequently in women and is most often diagnosed between the 5th and 6th decades of life, although cases have also been documented in children and young adults.[16][17][18]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of OLP is not fully understood. However, 2 primary mechanisms have been proposed: antigen-specific and nonspecific.[19]

The antigen-specific mechanism involves triggering events that expose OLP-specific antigens, leading to activation and recruitment of CD4+ helper T cells and subsequent release of pro-inflammatory T-helper 1 cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor α and interferon γ.[20] CD8+ T cell-mediated cytotoxicity targets the basal cell layer of the epithelium, resulting in basement membrane disruption, T-cell migration into the epithelium, and keratinocyte apoptosis.

The nonspecific mechanism involves mast cell activation, releasing pro-inflammatory mediators, such as proteases and upregulated matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). This process promotes T-cell infiltration of the superficial lamina propria, basement membrane disruption, and subsequent keratinocyte apoptosis.

The chronic course of OLP has been linked to activation of nuclear factor κB and inhibition of the transforming growth factor β-Smad signaling pathway, contributing to hyperkeratosis and the formation of characteristic white lesions.[21][22] Genetic polymorphisms within the 1st intron of the interferon γ promoter gene have also been proposed as risk factors for OLP development.[23][24]

Histopathology

The first histopathologic diagnostic criteria for OLP were proposed by the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Oral Precancerous Lesions in 1978. OLP lesions may display the following microscopic features:

- Orthokeratosis or parakeratosis

- Sawtooth rete ridges

- Civatte bodies

- Narrow band of eosinophilic material in the basement membrane

- Band-like zone of lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial lamina propria

- Liquefaction degeneration in the basal cell layer[25]

Many of these features were later recognized as nonspecific to OLP. A recent position paper by the American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology proposed updated histopathologic criteria to exclude lichenoid mimics and improve diagnostic accuracy. The revised criteria include the following:

- Band-like zone of lymphocytic infiltrate at the epithelium-lamina propria interface

- Liquefactive degeneration in the basal cell layer

- Lymphocytic exocytosis

- Absence of epithelial dysplasia and verrucous epithelial architectural changes

Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) of OLP samples typically reveals fibrinogen deposition in a shaggy pattern along the basement membrane zone, without immunoglobulins or complement components.[26][27] Since histologic findings are not entirely specific, detailed patient history and clinical correlation are essential for a conclusive diagnosis.

History and Physical

Approximately 2/3 of patients with OLP are symptomatic, exhibiting alternating periods of exacerbation and quiescence. Symptom severity varies, but patients commonly report oral pain, sensitivity to spicy or acidic foods, and a sensation of mucosal roughness or tightness.[28]

OLP is classified into 6 clinical subtypes: reticular, papular, plaque, atrophic, erosive, and bullous.[29] These forms may occur independently or concurrently, with classification determined by the predominant subtype.

The reticular, erosive, and plaque forms are the most frequently encountered. Reticular OLP demonstrates the classic white lacy network of Wickham striae with hyperkeratotic plaques (see Image. Reticular Oral Lichen Planus). The erosive and atrophic OLP subtypes usually present with erythema and ulceration, often accompanied by pain and mucosal sensitivity. The peripheries of these lesions may show reticular keratotic striae. Papular and plaque variants manifest as white keratotic papules or plaques, potentially mimicking leukoplakia. In patients with darker skin tones, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may be observed as diffuse brown or black discoloration in association with the lesions.[30]

OLP usually demonstrates bilateral distribution, most commonly affecting the buccal mucosa, tongue, and gingiva, followed by the labial mucosa and lower lip. The Koebner phenomenon, characterized by lesion development at sites of mechanical trauma such as friction from sharp teeth, rough dental restorations, or lip and cheek biting, may explain this predilection for trauma-prone sites.[31][32] Approximately 10% of patients present with lesions limited to the gingiva, typically manifesting as desquamative gingivitis.

Evaluation

Correct diagnosis of OLP requires comprehensive history taking, detailed clinical examination, and histopathologic confirmation. In patients with the characteristic reticular form, clinical features alone may be sufficiently diagnostic. However, oral biopsy may still be considered to confirm the diagnosis and exclude dysplasia or malignancy.

In cases presenting with desquamative gingivitis, DIF is valuable for excluding autoimmune vesiculobullous disorders such as pemphigus and pemphigoid. Shaggy fibrinogen and complement deposition may be observed along the basement membrane zone, although this finding is not pathognomonic for OLP. Indirect immunofluorescence has limited diagnostic utility in evaluating this condition.

Treatment / Management

Mild OLP is frequently asymptomatic. When discomfort occurs, topical corticosteroids constitute the 1st-line treatment. Analgesic mouthwashes such as benzydamine provide pain relief, particularly before meals. Corticosteroids may be applied as an adhesive gel or administered as a mouth rinse. Topical therapy is preferred because of its efficacy and lower risk of systemic adverse effects. Although triamcinolone acetonide gel is widely used, higher-potency corticosteroids such as clobetasol propionate demonstrate superior symptomatic relief.[33]

Patients using topical gel should dry the oral mucosa before application and avoid eating or drinking for at least 30 minutes to ensure adequate mucosal contact. Dexamethasone mouth rinses are especially useful for patients with widespread or anatomically inaccessible lesions.[34][35](A1)

Intralesional corticosteroid injections may be administered for persistent erosive OLP.[36] Oropharyngeal candidiasis is one of the most common adverse effects of topical corticosteroids. Adjunctive topical or systemic antifungal therapy may be warranted when clinically indicated.[37] (A1)

Systemic corticosteroids are reserved for recalcitrant OLP unresponsive to topical treatment, severe disease with extensive ulceration and erythema, or lichen planus with multisite extraoral involvement. Short courses of systemic corticosteroids may achieve rapid control of persistent lesions. Dosage and frequency should be tapered as lesions resolve or symptoms improve to minimize adverse effects.

Second-line therapies may be considered for recalcitrant OLP unresponsive to topical corticosteroids. Options include calcineurin inhibitors (eg, cyclosporine, tacrolimus), retinoids, and steroid-sparing agents such as azathioprine, hydroxychloroquine, or mycophenolate mofetil. Transient burning sensation is the most frequently reported adverse effect associated with retinoids and cyclosporine, often limiting use in patients with erosive OLP.[38](A1)

Use of newer calcineurin inhibitors, including tacrolimus, requires caution because of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's black box warning citing a potential increased risk of squamous cell carcinoma and lymphoma. Retinoids are contraindicated in pregnancy owing to teratogenicity.[39] Steroid-sparing agents must be prescribed with care, as azathioprine carries a risk of bone marrow aplasia, and hydroxychloroquine is associated with retinal toxicity.(A1)

Differential Diagnosis

Several conditions mimic OLP both clinically and histologically, including oral lichenoid drug reactions, oral lichenoid contact hypersensitivity, mucous membrane pemphigoid, chronic graft-versus-host disease, lupus erythematosus, lichen planus pemphigoides, chronic ulcerative stomatitis, proliferative verrucous leukoplakia, and oral epithelial dysplasia.[40] Key clinical and histopathologic distinctions between OLP and its most significant differential diagnoses are outlined below.

Oral Lichenoid Drug Reaction

Numerous medications can precipitate oral lichenoid reactions, producing reticular or atrophic-erosive lesions with an onset ranging from several weeks to over a year after drug initiation. Frequently implicated medications include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antihypertensives, anticonvulsants, antimalarials, and antiretrovirals.[41][42] Additional agents include oral hypoglycemics, dapsone, gold salts, penicillamine, and phenothiazines. Diagnosis is challenging and relies heavily on a detailed medication history. Collaboration with the prescribing clinician may be warranted to determine the feasibility of replacing the suspected drug, followed by careful monitoring for lesion resolution, which may require several months.

Oral Lichenoid Contact Hypersensitivity Reaction

Oral lichenoid contact hypersensitivity reactions develop on mucosal surfaces in direct contact with the triggering agent. Implicated agents include dental restorative materials (eg, metals, composites, glass ionomer cement) and flavoring agents (eg, menthol, eugenol).[43] Amalgam restorations are the most frequently associated cause.[44][45][46] Lesions commonly occur on the buccal mucosa or lateral tongue adjacent to the restoration. Clinical resolution is typically observed within several months after replacement of the restoration or discontinuation of the flavoring agent.[47]

Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease

Oral involvement occurs in approximately 80% of patients undergoing allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Lichenoid lesions may affect any oral mucosal site, typically developing around 6 months posttransplantation. Diagnosis requires careful clinical correlation with transplantation history and systemic manifestations.

Lichen Planus Pemphigoides

Lichen planus pemphigoides is a rare mucocutaneous blistering disorder that exhibits both clinical and histopathologic features of OLP and mucous membrane pemphigoid. Oral involvement is reported in approximately 24% of patients, most commonly affecting the gingiva and buccal mucosa. DIF findings are indistinguishable from those of mucous membrane pemphigoid.

Chronic Ulcerative Stomatitis

This condition predominantly affects women in the 5th and 6th decades of life. Patients present with chronic oral ulcerations involving the gingiva, tongue, and buccal mucosa. Gingival involvement may manifest as desquamative gingivitis. Histopathologic findings closely resemble those of OLP, but perilesional tissue demonstrates deposition of immunoglobulin G autoantibodies within the nuclei of basal and parabasal epithelial cells in a characteristic speckled pattern.

Lupus Erythematosus

Both discoid and systemic lupus erythematosus can involve the oral mucosa. Lesions demonstrate central ulceration and atrophy with surrounding erythema and radiating white striae. The buccal mucosa, hard palate, and gingiva are common sites of involvement. Cutaneous lesions may coexist, and serologic evaluation frequently reveals positive antinuclear antibody titers.[48]

Prognosis

Lifestyle modifications and pharmacologic therapy can relieve symptoms and improve quality of life. Long-term clinical surveillance facilitates early detection of malignant transformation and supports a more favorable prognosis.

Complications

The malignant potential of OLP remains a subject of debate. Reported rates of transformation to squamous cell carcinoma range from 0% to 12.5%, reflecting substantial variability in study inclusion and exclusion criteria.[49][50][51][52][53] Most cases of malignant transformation are reported in patients with atrophic or erosive OLP.

A meta-analysis estimated the malignant transformation rate at 0.44%. Risk is increased in patients who smoke, consume alcohol, are seropositive for HCV, or present with the red subtypes of OLP.[54] Despite variability in reported rates, evidence consistently supports routine long-term follow-up for symptom management and surveillance for malignant change.

Several molecular and cellular factors have been associated with malignant transformation in OLP. Overexpression of MMPs (MMP-1, MMP-2, and MMP-9) and the c-Myc protein, altered salivary cortisol and nitric oxide levels, and dysregulated interleukin expression have been implicated in disease progression. Viral agents, including HCV, human papillomavirus, and Epstein–Barr virus, along with environmental carcinogens such as tobacco and alcohol, act as cofactors. At the molecular level, alterations in p16, p21, p53, and mRNA26 may contribute to malignant transformation. Whether malignant transformation develops as an intrinsic consequence of OLP or is primarily driven by these associated risk factors remains debated.

Chronic inflammation, similar to that seen in colitis-associated cancer, is considered a key driver of malignant transformation in OLP.[55] Inflammatory mediators can induce DNA damage, promote cell proliferation, inhibit apoptosis, and trigger protein alterations within oral epithelial cells.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with OLP should be counseled that treatment primarily targets symptomatic relief. Lifestyle modifications, including avoidance of acidic or spicy foods, can reduce symptom severity.[56] Eliminating potential local exacerbating factors, such as adjusting sharp teeth or defective dental restorations, along with patient education on optimal oral hygiene and stress management, is essential for long-term disease control.[57] Discussing the low but clinically significant risk of malignant transformation is important to underscore the need for ongoing clinical surveillance. Regular follow-up facilitates early detection of concerning changes, including persistent ulcerations or mucosal growths.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

OLP can pose a diagnostic challenge, as patients often present with nonspecific features that resemble other mucosal disorders. Accurate diagnosis requires a comprehensive history, clinical examination, and histopathologic assessment. Management is generally coordinated by a dentist, oral medicine specialist, or oral surgeon. Interprofessional collaboration with dermatologists, gynecologists, gastroenterologists, otorhinolaryngologists, or ophthalmologists may be warranted in patients with extraoral involvement. Pharmacotherapy, patient education, and lifestyle modification remain the cornerstone of OLP management and are critical for optimizing outcomes. Ongoing research is needed to elucidate the condition's pathogenesis and clinical course further.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Gururaj N, Hasinidevi P, Janani V, Divynadaniel T. Diagnosis and management of oral lichen planus - Review. Journal of oral and maxillofacial pathology : JOMFP. 2021 Sep-Dec:25(3):383-393. doi: 10.4103/jomfp.jomfp_386_21. Epub 2022 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 35281147]

Farhi D, Dupin N. Pathophysiology, etiologic factors, and clinical management of oral lichen planus, part I: facts and controversies. Clinics in dermatology. 2010 Jan-Feb:28(1):100-8. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2009.03.004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20082959]

Gorouhi F, Davari P, Fazel N. Cutaneous and mucosal lichen planus: a comprehensive review of clinical subtypes, risk factors, diagnosis, and prognosis. TheScientificWorldJournal. 2014:2014():742826. doi: 10.1155/2014/742826. Epub 2014 Jan 30 [PubMed PMID: 24672362]

Parashar P. Oral lichen planus. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2011 Feb:44(1):89-107, vi. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2010.09.004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21093625]

Eisen D. The evaluation of cutaneous, genital, scalp, nail, esophageal, and ocular involvement in patients with oral lichen planus. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology, oral radiology, and endodontics. 1999 Oct:88(4):431-6 [PubMed PMID: 10519750]

Eisen D. The clinical manifestations and treatment of oral lichen planus. Dermatologic clinics. 2003 Jan:21(1):79-89 [PubMed PMID: 12622270]

Rogers RS 3rd, Eisen D. Erosive oral lichen planus with genital lesions: the vulvovaginal-gingival syndrome and the peno-gingival syndrome. Dermatologic clinics. 2003 Jan:21(1):91-8, vi-vii [PubMed PMID: 12622271]

Abraham SC, Ravich WJ, Anhalt GJ, Yardley JH, Wu TT. Esophageal lichen planus: case report and review of the literature. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2000 Dec:24(12):1678-82 [PubMed PMID: 11117791]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFox LP, Lightdale CJ, Grossman ME. Lichen planus of the esophagus: what dermatologists need to know. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2011 Jul:65(1):175-83. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.03.029. Epub 2011 May 4 [PubMed PMID: 21536343]

Katzka DA, Smyrk TC, Bruce AJ, Romero Y, Alexander JA, Murray JA. Variations in presentations of esophageal involvement in lichen planus. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2010 Sep:8(9):777-82. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.04.024. Epub 2010 May 13 [PubMed PMID: 20471494]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJung W, Jang S. Oral Microbiome Research on Oral Lichen Planus: Current Findings and Perspectives. Biology. 2022 May 9:11(5):. doi: 10.3390/biology11050723. Epub 2022 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 35625451]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYu FY, Wang QQ, Li M, Cheng YH, Cheng YL, Zhou Y, Yang X, Zhang F, Ge X, Zhao B, Ren XY. Dysbiosis of saliva microbiome in patients with oral lichen planus. BMC microbiology. 2020 Apr 3:20(1):75. doi: 10.1186/s12866-020-01733-7. Epub 2020 Apr 3 [PubMed PMID: 32245419]

Chen J, Liu K, Sun X, Shi X, Zhao G, Yang Z. Microbiome landscape of lesions and adjacent normal mucosal areas in oral lichen planus patient. Frontiers in microbiology. 2022:13():992065. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.992065. Epub 2022 Oct 20 [PubMed PMID: 36338092]

Nukaly HY, Halawani IR, Alghamdi SMS, Alruwaili AG, Binhezaim A, Algahamdi RAA, Alzahrani RAJ, Alharamlah FSS, Aldumkh SHS, Alasqah HMA, Alamri A, Jfri A. Oral Lichen Planus: A Narrative Review Navigating Etiologies, Clinical Manifestations, Diagnostics, and Therapeutic Approaches. Journal of clinical medicine. 2024 Sep 5:13(17):. doi: 10.3390/jcm13175280. Epub 2024 Sep 5 [PubMed PMID: 39274493]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLi C, Tang X, Zheng X, Ge S, Wen H, Lin X, Chen Z, Lu L. Global Prevalence and Incidence Estimates of Oral Lichen Planus: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA dermatology. 2020 Feb 1:156(2):172-181. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3797. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31895418]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCarrozzo M, Gandolfo S. The management of oral lichen planus. Oral diseases. 1999 Jul:5(3):196-205 [PubMed PMID: 10483064]

Eisen D. The clinical features, malignant potential, and systemic associations of oral lichen planus: a study of 723 patients. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2002 Feb:46(2):207-14 [PubMed PMID: 11807431]

Eisen D, Carrozzo M, Bagan Sebastian JV, Thongprasom K. Number V Oral lichen planus: clinical features and management. Oral diseases. 2005 Nov:11(6):338-49 [PubMed PMID: 16269024]

Roopashree MR, Gondhalekar RV, Shashikanth MC, George J, Thippeswamy SH, Shukla A. Pathogenesis of oral lichen planus--a review. Journal of oral pathology & medicine : official publication of the International Association of Oral Pathologists and the American Academy of Oral Pathology. 2010 Nov:39(10):729-34. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2010.00946.x. Epub 2010 Oct 4 [PubMed PMID: 20923445]

Olson MA, Rogers RS 3rd, Bruce AJ. Oral lichen planus. Clinics in dermatology. 2016 Jul-Aug:34(4):495-504. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.02.023. Epub 2016 Mar 2 [PubMed PMID: 27343965]

Santoro A, Majorana A, Bardellini E, Festa S, Sapelli P, Facchetti F. NF-kappaB expression in oral and cutaneous lichen planus. The Journal of pathology. 2003 Nov:201(3):466-72 [PubMed PMID: 14595759]

Karatsaidis A, Schreurs O, Axéll T, Helgeland K, Schenck K. Inhibition of the transforming growth factor-beta/Smad signaling pathway in the epithelium of oral lichen. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2003 Dec:121(6):1283-90 [PubMed PMID: 14675171]

Carrozzo M, Uboldi de Capei M, Dametto E, Fasano ME, Arduino P, Broccoletti R, Vezza D, Rendine S, Curtoni ES, Gandolfo S. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma polymorphisms contribute to susceptibility to oral lichen planus. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2004 Jan:122(1):87-94 [PubMed PMID: 14962095]

Scully C, Carrozzo M. Oral mucosal disease: Lichen planus. The British journal of oral & maxillofacial surgery. 2008 Jan:46(1):15-21 [PubMed PMID: 17822813]

Kramer IR, Lucas RB, Pindborg JJ, Sobin LH. Definition of leukoplakia and related lesions: an aid to studies on oral precancer. Oral surgery, oral medicine, and oral pathology. 1978 Oct:46(4):518-39 [PubMed PMID: 280847]

Abell E, Presbury DG, Marks R, Ramnarain D. The diagnostic significance of immunoglobulin and fibrin deposition in lichen planus. The British journal of dermatology. 1975 Jul:93(1):17-24 [PubMed PMID: 1191524]

Crincoli V, Di Bisceglie MB, Scivetti M, Lucchese A, Tecco S, Festa F. Oral lichen planus: update on etiopathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Immunopharmacology and immunotoxicology. 2011 Mar:33(1):11-20. doi: 10.3109/08923973.2010.498014. Epub 2010 Jul 6 [PubMed PMID: 20604639]

Ismail SB, Kumar SK, Zain RB. Oral lichen planus and lichenoid reactions: etiopathogenesis, diagnosis, management and malignant transformation. Journal of oral science. 2007 Jun:49(2):89-106 [PubMed PMID: 17634721]

Andreasen JO. Oral lichen planus. 1. A clinical evaluation of 115 cases. Oral surgery, oral medicine, and oral pathology. 1968 Jan:25(1):31-42 [PubMed PMID: 5235654]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMergoni G, Ergun S, Vescovi P, Mete Ö, Tanyeri H, Meleti M. Oral postinflammatory pigmentation: an analysis of 7 cases. Medicina oral, patologia oral y cirugia bucal. 2011 Jan 1:16(1):e11-4 [PubMed PMID: 20526252]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRamón-Fluixá C, Bagán-Sebastián J, Milián-Masanet M, Scully C. Periodontal status in patients with oral lichen planus: a study of 90 cases. Oral diseases. 1999 Oct:5(4):303-6 [PubMed PMID: 10561718]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAl-Hashimi I, Schifter M, Lockhart PB, Wray D, Brennan M, Migliorati CA, Axéll T, Bruce AJ, Carpenter W, Eisenberg E, Epstein JB, Holmstrup P, Jontell M, Lozada-Nur F, Nair R, Silverman B, Thongprasom K, Thornhill M, Warnakulasuriya S, van der Waal I. Oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid lesions: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology, oral radiology, and endodontics. 2007 Mar:103 Suppl():S25.e1-12 [PubMed PMID: 17261375]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDavari P, Hsiao HH, Fazel N. Mucosal lichen planus: an evidence-based treatment update. American journal of clinical dermatology. 2014 Jul:15(3):181-95. doi: 10.1007/s40257-014-0068-6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24781705]

Schlosser BJ. Lichen planus and lichenoid reactions of the oral mucosa. Dermatologic therapy. 2010 May-Jun:23(3):251-67. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2010.01322.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20597944]

Carbone M, Goss E, Carrozzo M, Castellano S, Conrotto D, Broccoletti R, Gandolfo S. Systemic and topical corticosteroid treatment of oral lichen planus: a comparative study with long-term follow-up. Journal of oral pathology & medicine : official publication of the International Association of Oral Pathologists and the American Academy of Oral Pathology. 2003 Jul:32(6):323-9 [PubMed PMID: 12787038]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceXia J, Li C, Hong Y, Yang L, Huang Y, Cheng B. Short-term clinical evaluation of intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injection for ulcerative oral lichen planus. Journal of oral pathology & medicine : official publication of the International Association of Oral Pathologists and the American Academy of Oral Pathology. 2006 Jul:35(6):327-31 [PubMed PMID: 16762012]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceVincent SD, Fotos PG, Baker KA, Williams TP. Oral lichen planus: the clinical, historical, and therapeutic features of 100 cases. Oral surgery, oral medicine, and oral pathology. 1990 Aug:70(2):165-71 [PubMed PMID: 2290644]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGiustina TA, Stewart JC, Ellis CN, Regezi JA, Annesley T, Woo TY, Voorhees JJ. Topical application of isotretinoin gel improves oral lichen planus. A double-blind study. Archives of dermatology. 1986 May:122(5):534-6 [PubMed PMID: 3518638]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHersle K, Mobacken H, Sloberg K, Thilander H. Severe oral lichen planus: treatment with an aromatic retinoid (etretinate). The British journal of dermatology. 1982 Jan:106(1):77-80 [PubMed PMID: 7037037]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCheng YS, Gould A, Kurago Z, Fantasia J, Muller S. Diagnosis of oral lichen planus: a position paper of the American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology and oral radiology. 2016 Sep:122(3):332-54. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2016.05.004. Epub 2016 Jul 9 [PubMed PMID: 27401683]

Khudhur AS, Di Zenzo G, Carrozzo M. Oral lichenoid tissue reactions: diagnosis and classification. Expert review of molecular diagnostics. 2014 Mar:14(2):169-84. doi: 10.1586/14737159.2014.888953. Epub 2014 Feb 13 [PubMed PMID: 24524807]

Müller S. Oral manifestations of dermatologic disease: a focus on lichenoid lesions. Head and neck pathology. 2011 Mar:5(1):36-40. doi: 10.1007/s12105-010-0237-8. Epub 2011 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 21221868]

Issa Y, Duxbury AJ, Macfarlane TV, Brunton PA. Oral lichenoid lesions related to dental restorative materials. British dental journal. 2005 Mar 26:198(6):361-6; disussion 549; quiz 372 [PubMed PMID: 15789104]

Thornhill MH, Pemberton MN, Simmons RK, Theaker ED. Amalgam-contact hypersensitivity lesions and oral lichen planus. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology, oral radiology, and endodontics. 2003 Mar:95(3):291-9 [PubMed PMID: 12627099]

Laeijendecker R, Dekker SK, Burger PM, Mulder PG, Van Joost T, Neumann MH. Oral lichen planus and allergy to dental amalgam restorations. Archives of dermatology. 2004 Dec:140(12):1434-8 [PubMed PMID: 15611418]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLópez-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F, Gomez-Garcia F, Bermejo Fenoll A. The clinicopathological characteristics of oral lichen planus and its relationship with dental materials. Contact dermatitis. 2004 Oct:51(4):210-1 [PubMed PMID: 15500671]

Thornhill MH, Sankar V, Xu XJ, Barrett AW, High AS, Odell EW, Speight PM, Farthing PM. The role of histopathological characteristics in distinguishing amalgam-associated oral lichenoid reactions and oral lichen planus. Journal of oral pathology & medicine : official publication of the International Association of Oral Pathologists and the American Academy of Oral Pathology. 2006 Apr:35(4):233-40 [PubMed PMID: 16519771]

Chiang CP, Yu-Fong Chang J, Wang YP, Wu YH, Lu SY, Sun A. Oral lichen planus - Differential diagnoses, serum autoantibodies, hematinic deficiencies, and management. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association = Taiwan yi zhi. 2018 Sep:117(9):756-765. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2018.01.021. Epub 2018 Feb 19 [PubMed PMID: 29472048]

Lodi G, Scully C, Carrozzo M, Griffiths M, Sugerman PB, Thongprasom K. Current controversies in oral lichen planus: report of an international consensus meeting. Part 2. Clinical management and malignant transformation. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology, oral radiology, and endodontics. 2005 Aug:100(2):164-78 [PubMed PMID: 16037774]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGiuliani M, Troiano G, Cordaro M, Corsalini M, Gioco G, Lo Muzio L, Pignatelli P, Lajolo C. Rate of malignant transformation of oral lichen planus: A systematic review. Oral diseases. 2019 Apr:25(3):693-709. doi: 10.1111/odi.12885. Epub 2018 Jun 25 [PubMed PMID: 29738106]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFitzpatrick SG, Hirsch SA, Gordon SC. The malignant transformation of oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid lesions: a systematic review. Journal of the American Dental Association (1939). 2014 Jan:145(1):45-56. doi: 10.14219/jada.2013.10. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24379329]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGonzález-Moles MÁ, Ruiz-Ávila I, González-Ruiz L, Ayén Á, Gil-Montoya JA, Ramos-García P. Malignant transformation risk of oral lichen planus: A systematic review and comprehensive meta-analysis. Oral oncology. 2019 Sep:96():121-130. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2019.07.012. Epub 2019 Jul 22 [PubMed PMID: 31422203]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGonzalez-Moles MA, Scully C, Gil-Montoya JA. Oral lichen planus: controversies surrounding malignant transformation. Oral diseases. 2008 Apr:14(3):229-43. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2008.01441.x. Epub 2008 Feb 22 [PubMed PMID: 18298420]

Idrees M, Kujan O, Shearston K, Farah CS. Oral lichen planus has a very low malignant transformation rate: A systematic review and meta-analysis using strict diagnostic and inclusion criteria. Journal of oral pathology & medicine : official publication of the International Association of Oral Pathologists and the American Academy of Oral Pathology. 2021 Mar:50(3):287-298. doi: 10.1111/jop.12996. Epub 2020 Feb 8 [PubMed PMID: 31981238]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceManchanda Y, Rathi SK, Joshi A, Das S. Oral Lichen Planus: An Updated Review of Etiopathogenesis, Clinical Presentation, and Management. Indian dermatology online journal. 2024 Jan-Feb:15(1):8-23. doi: 10.4103/idoj.idoj_652_22. Epub 2023 Dec 22 [PubMed PMID: 38283029]

Lodi G, Scully C, Carrozzo M, Griffiths M, Sugerman PB, Thongprasom K. Current controversies in oral lichen planus: report of an international consensus meeting. Part 1. Viral infections and etiopathogenesis. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology, oral radiology, and endodontics. 2005 Jul:100(1):40-51 [PubMed PMID: 15953916]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceStone SJ, McCracken GI, Heasman PA, Staines KS, Pennington M. Cost-effectiveness of personalized plaque control for managing the gingival manifestations of oral lichen planus: a randomized controlled study. Journal of clinical periodontology. 2013 Sep:40(9):859-67. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12126. Epub 2013 Jun 25 [PubMed PMID: 23800196]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence