Introduction

Extraction of unerupted teeth is a standard dental procedure performed by various dental specialties, from general dentistry to oral surgery. Dental impaction is common and can occur with all maxillary and mandibular teeth.[1] Contrary to popular belief, not all unerupted teeth are considered impacted. A tooth that has failed to erupt within its timeframe can be either retained or impacted. The difference is that a retained tooth has no physical obstruction on its pathway and appears to have eruption potential on radiographic examination. In contrast, an impacted tooth denotes a physical obstruction, such as an adjacent tooth, bone, or soft tissue.[2] Impaction can be partial or complete, single or multiple, depending on the degree of impaction and the number of impacted teeth.

Diagnosis relies on clinical examination and radiographic imaging techniques such as periapical radiographs, panoramic radiographs, and cone beam computed tomography (CBCT). These imaging methods provide insights into the tooth's position and adjacent structures, aiding treatment planning. This activity reviews the management and extraction techniques for teeth that have failed to erupt.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Tooth eruption is the movement of the developing tooth from its position in the alveolar bone to the occlusal plane. For a tooth to erupt, it has to remove the alveolar bone and primary roots in its pathway and, later, the soft tissues. A propulsive force that moves the tooth in an occlusal direction along this eruption pathway is also required. Bone resorption occlusal to the unerupted tooth is believed to create an eruption pathway first. Then, bone apposition apical to the tooth generates propulsive occlusal movements, following the path. Various theories have been described to explain the physiology of dental eruption. The most widely accepted theory advocates that the dental follicle regulates bone remodeling mechanisms necessary for translocating the tooth through the eruption pathway to the alveolar crest.[3]

Tooth impaction may affect anyone, with incidence rates varying from 5.6% to 18.8%, and it tends to be more common in female individuals. The frequency of tooth impaction follows a pattern opposite to the typical chronological eruption sequence. Teeth that erupt later are more likely to be impacted due to insufficient arch space. The mandibular 3rd molar is the most commonly impacted tooth, followed by the maxillary 3rd molar, maxillary canine, mandibular premolars, maxillary premolars, and 2nd molar. The teeth with the lowest impaction rates are the mandibular incisors, 1st molars, and primary teeth. Impaction of these teeth is relatively rare and is typically associated with specific conditions, such as retained deciduous teeth or abnormalities like an odontoma.

Inadequate arch length and space are the main reasons for eruption failure of individual teeth.[4] Various conditions may present with multiple dental impactions, including Gardner and Gorlin syndromes and cleidocranial dysostosis.[5] Other causes of multiple impactions are metabolic and hormonal disorders. Impacted teeth often promote the development of pathologies such as cysts or tumors, dental caries, root resorption, and periodontal disease.

Vital anatomical structures in the oral cavity should be considered when assessing impacted teeth. A basic understanding of these structures is necessary to avoid untoward complications.

Mandibular Third Molar

Extraction of impacted mandibular 3rd molars is a routine procedure in dental practice, as these teeth are most likely to develop some degree of impaction. The position of the mandibular 3rd molar serves as a key indicator of extraction complexity. Several classification systems, including Winter and Pell and Gregory, have been created to anticipate the difficulty of extracting the 3rd molar.

Winter classification

The Winter classification describes mandibular 3rd molars based on the angulation of the crown with respect to the long axis of the 2nd molar. The Winter classification is as follows:

- Vertical

- Mesioangular

- Distoangular

- Horizontal

- Buccolingual

- Inverted

- Other Orientation

Horizontal and distoangular impactions are more difficult to extract, as the path of delivery of the tooth is obstructed by overlying bone and the ascending ramus.

Pell and Gregory classification

The classification by Pell and Gregory describes impacted mandibular 3rd molars on the vertical and horizontal planes. The vertical relation of the impacted 3rd molar to the occlusal plane of the mandibular 2nd molar is classified as levels A, B, and C. The horizontal relation of the impacted molar with the anterior border of the mandibular ramus is classified as classes 1, 2, and 3.[6] The Pell and Gregory classification is as follows:

- Level A: The occlusal plane of the 3rd molar is above or at the level of the occlusal plane of the 2nd molar.

- Level B: The occlusal plane of the 3rd molar is between the occlusal plane and the cementoenamel junction of the 2nd molar.

- Level C: The occlusal plane of the 3rd molar is below the cementoenamel junction of the 2nd molar.

- Class 1: The crown of the 3rd molar is completely anterior to the ascending ramus.

- Class 2: The crown of the 3rd molar is partially within the mandibular ramus.

- Class 3: The crown of the 3rd molar is completely within the mandibular ramus.

Class 3 and level C are the most complex cases, as more bone must be removed to access the tooth.

Inferior Alveolar Nerve

The inferior alveolar nerve (IAN) is a branch of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve and is responsible for sensory innervation to the mandibular teeth, gingiva, lower lip, and chin. The IAN lies near the apices of mandibular molars. Therefore, the proximity of the 3rd molar to the IAN must be carefully assessed to determine the risk of postoperative sensory complications. Sensory alterations from IAN injuries tend to be temporary, with a 1% to 5% risk. The risk of permanent sensory disturbances is less, estimated to lie between 0% and 0.9%.[7]

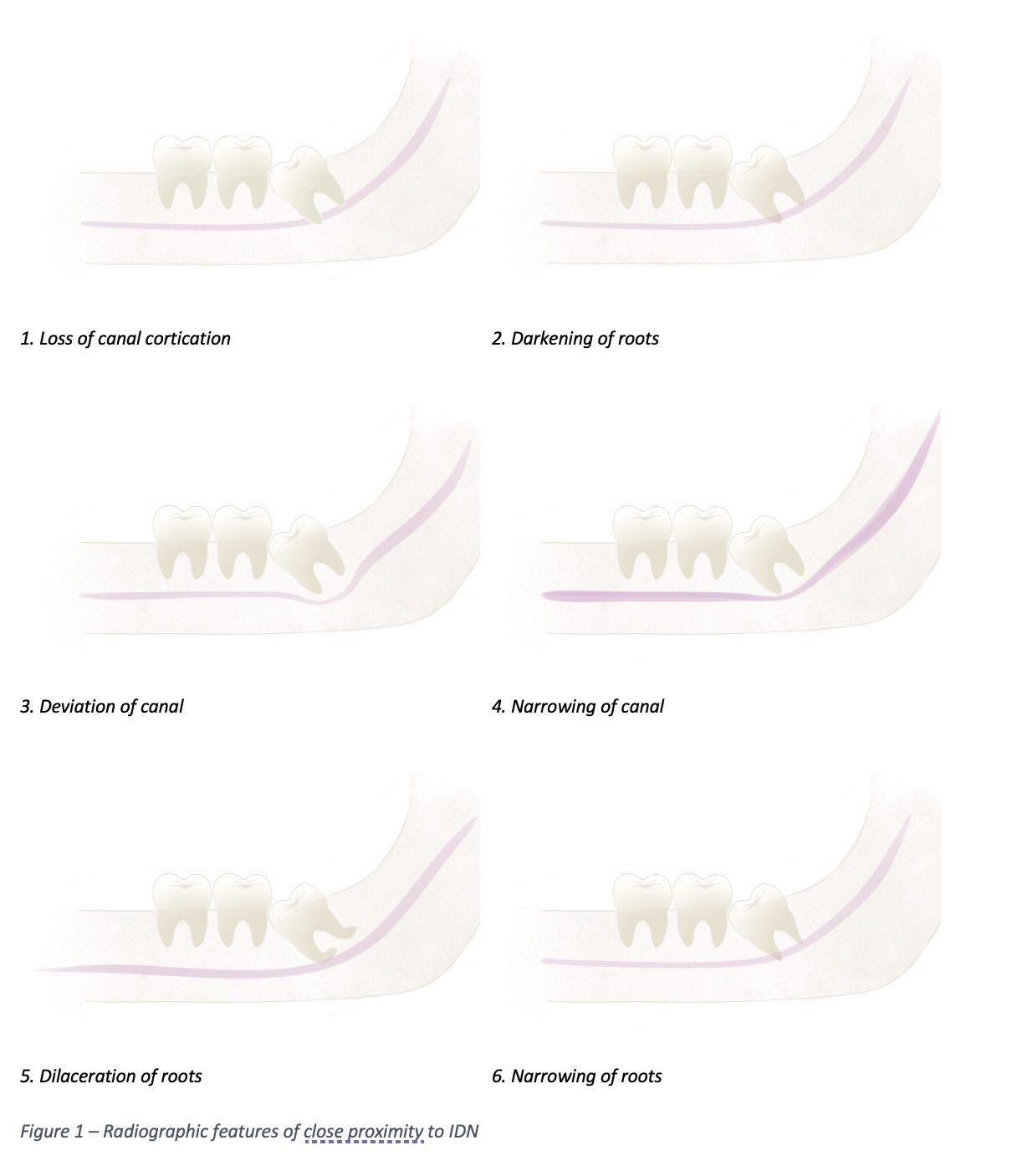

The Rood classification is a valuable assessment tool that uses radiographs to predict IAN injury in 3rd molar extractions.[8] Several radiographic features on panoramic radiographs suggest proximity to the IAN, and the presence of 1 or more of these signs warrants a more complex imaging examination by CBCT. Signs to watch for include the loss of cortication of the inferior dental canal (IDC), seen as an interruption of the radiopaque line that lies above and below the IAN canal narrowing, alongside deviation of the IDC, darkening or narrowing of the roots, and dilaceration of the roots (see Image. Radiographic Features Suggestive of Close Proximity to the Inferior Dental Canal).[9]

Mental Nerve

The mental nerve is the terminal branch of the IAN. This nerve is responsible for the sensory innervation of the gingiva, lower lip, and skin of the chin ventral to the mental foramen.[10] The mental nerve may also provide some innervation to the mandibular incisors.[11]

The IAN becomes the mental nerve as it leaves the mental foramen and is found to branch either into 1, 2, or 3 branches at, or immediately after, it exits the mental foramen.[12] Before exiting the mental foramen, the IAN may pass beyond this foramen and create a loop in an anteroinferior direction of variable distance.[13] The mental foramen lies between the 2 mandibular premolars in 50.4% to 61.95% of cases and apical to the 2nd premolar in 50.3% to 57.9% of cases.[14] Careful consideration of the mental nerve and the anterior loop of the IAN with appropriate imaging is critical when planning the extraction of an impacted mandibular tooth.

Lingual Nerve

The lingual nerve is a branch of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve and is joined by the chorda tympani nerve, a branch of the facial nerve, to give sensory innervation and taste sensation to the anterior 2/3 of the tongue. As the lingual nerve branches off the mandibular nerve inferiorly, it passes between the lateral surface of the medial pterygoid and the lingual surface of the ramus in the retromolar pad region, where it is at risk of injury during the extraction of mandibular molars.[15]

Studies on the position of the lingual nerve found it lying below the alveolar crest in 77.87% of examined nerves and above the alveolar crest in 8.21%.[16] Furthermore, the lingual nerve was found to be located an average of 2.06 mm horizontally from the lingual plate, 3.01 mm vertically from the lingual crest, and in direct contact with the lingual plate in 22.27% of cases.[17]

Maxillary Sinus

The maxillary sinus is a pyramidal air-filled cavity confined by the nasal cavity medially, the infraorbital rim superiorly, the alveolar process inferiorly, and the zygomatic process laterally. The floor of the maxillary sinus extends anteriorly to the premolar-canine region and posteriorly to the maxillary tuberosity, which can complicate extractions of impacted maxillary teeth.[18]

Indications

Not all impacted teeth require surgical intervention. Extractions should prioritize minimizing injury to teeth and surrounding tissues. Indications for removing unerupted or impacted teeth include infections causing pain, caries, periodontal disease, apical pathology, insufficient arch space for eruption, ectopic eruption, and damage to adjacent teeth. Additional indications include performing prophylactic extractions for medical or surgical purposes, extracting teeth in the line of a bony fracture, addressing traumatic injuries, and facilitating trauma management or orthognathic surgery.[19]

Unerupted teeth are often asymptomatic and disease-free but still extracted prophylactically in healthy patients despite limited evidence supporting the effectiveness of this approach.[20] In cases where repositioning impacted teeth within the alveolar bone is not feasible, extraction may be the only treatment option. Factors such as age, tooth position and health, adjacent teeth, arch length, and occlusal relationship should be carefully evaluated before extraction.

Research indicates that certain factors, such as being female, having retained lower primary canines, delaying treatment, and having maxillary peg lateral incisors, can increase the severity of impaction.[21] These factors should be considered when planning preventive or interceptive procedures in young patients. If left untreated, unerupted or impacted teeth can lead to numerous complications, such as pain, infection, crown resorption, root resorption and displacement of neighboring teeth, ankylosis, and infraocclusion.

Contraindications

Some limitations of extracting unerupted teeth include systemic conditions, intake of certain medications, and tooth-related factors. Careful assessment of patient-specific factors is essential to minimize risks and complications.

Epilepsy

Patients with epilepsy are at risk of aspiration and self-harm, including potential seizure activity during dental extraction.[22] Close collaboration with the patient’s neurologist may help optimize seizure control prior to the procedure.

Cerebrovascular Diseases

A recent history of transient ischemic attack increases the risk of stroke during dental procedures. A thorough medical evaluation is necessary to mitigate these risks.

Cardiovascular Diseases

Further evaluation is necessary for patients with preexisting cardiovascular disease, including ischemic heart disease, dysrhythmias, infective endocarditis, uncontrolled hypertension, and severe coronary artery disease.[23] Uncontrolled cardiovascular disease can precipitate tissue infarction or a stroke.

Patients who have a high risk of developing infective endocarditis or have had it in the past may need antibiotic prophylaxis. Consultation with a cardiologist or primary care provider is recommended.[24]

Renal and Liver Disease

Patients with severe renal impairment or liver disease are at increased risk of bleeding and infection.[25] Surgical procedures should be avoided in these patients whenever feasible.

Immunosuppression

Recipients of organ transplants and other patients with poor immune status have a greater risk of systemic infections following invasive dental treatment. The efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis is unclear in these patients. Careful evaluation and personalized recommendations are necessary.

Bleeding Disorders and Anticoagulant Therapy Use

Patients who have bleeding disorders or take anticoagulants are at increased risk of excessive bleeding during dental extractions. Studies recommend continuing anticoagulant therapy for invasive procedures, as the risks associated with discontinuation outweigh the benefits of bleeding control.

The international normalized ratio (INR) measures bleeding tendency and is monitored in individuals taking warfarin. An INR below 4.0 is generally acceptable.[26] INR should be measured within 72 hours of the procedure. Local hemostatic measures are advised.

Use of Radiation Therapy and Antiresorptive Agents

Ongoing or recent radiation therapy in the head and neck increases the risk of developing osteoradionecrosis after extraction. Osteoradionecrosis manifests as nonhealing bone exposed to the oral cavity.[27] Preventing such complications requires a thorough dental examination and addressing any active infections before initiating radiotherapy.

Antiresorptive agents such as bisphosphonates are prescribed for managing bone conditions, such as osteoporosis, multiple myeloma, Paget disease of bone, and hypercalcemia of malignancy.[28] Patients taking antiresorptive agents have a higher risk of developing osteonecrosis, a condition known as medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws (MRONJ). Similar to osteoradionecrosis, MRONJ presents as a nonhealing extraction socket with or without exposed bone due to inhibition of bone remodeling.[29] Risk factors for developing MRONJ include concurrent steroid use, advanced age, and use of antiresorptive agents for over 5 years.[30] A drug holiday, which involves discontinuing antiresorptive medication, is not indicated.

Tooth Proximity to Vital Structures

Tooth proximity to vital structures is another limitation to the extraction of unerupted teeth. Mandibular 3rd molar roots are often too close to the IAN. The Roods criteria demonstrate the radiographic prediction of IAN injury during mandibular 3rd molar extractions. A coronectomy may be indicated as an alternative to extraction to prevent nerve damage.[31]

Extraction of unerupted maxillary teeth can lead to an oroantral communication (OAC) if the tooth is in close proximity to the floor of the maxillary sinus. Radiographic images are required for a proper evaluation of impacted tooth-sinus proximity.

Preparation

A thorough clinical examination and detailed medical history are essential for diagnosing and planning the extraction of an impacted tooth. Radiographic imaging, such as panoramic, periapical, occlusal x-rays, computed tomography, or CBCT, determines the tooth's position, inclination, and relationship to adjacent anatomical structures. The 3-dimensional reconstruction offered by CBCT provides the most accurate evaluation, making it the preferred diagnostic tool when a more detailed visualization is needed. Radiographs of the surgical site must also include key anatomical landmarks. Panoramic images may be supplemented with periapical images using the Same Lingual Opposite Buccal (SLOB) technique to accurately determine the position of impacted teeth that overlap with adjacent teeth.

Before extraction, the surgeon must conduct a comprehensive evaluation, including medical history, physical examination, and appropriate imaging. Patients should be informed about the procedure's risks, benefits, and alternatives and provide written consent.

Technique or Treatment

The general technique for extracting unerupted or impacted teeth can be divided into 3 main steps:

- Reflection of an adequately sized flap to allow access

- Removal of the bone surrounding the impacted tooth

- Luxation and removal of the tooth

The 2 basic surgical flap designs used in dentoalveolar surgery are full-thickness mucoperiosteal flap and split-thickness mucoperiosteal flap.[32] Maintenance of flap perfusion is critical. The tissue flap should have a broad base to ensure proper blood supply to the flap margins.

When designing a flap, releasing incisions must be incorporated with care, as they are not always indicated and can complicate healing. Releasing incisions are contraindicated in the palate, the lingual surface of the mandible, the canine eminence, and near the mental foramen.

The envelope flap is one of the more commonly used for extracting impacted mandibular molars. This flap should extend from the 1st molar to the posterior aspect of the impacted tooth. The flap should also reflect laterally toward the external oblique ridge.

The surgical handpiece used for bone removal must exhaust air pressure away from the surgical site to avoid air embolism or tissue emphysema. Lingual bone removal must be avoided to prevent injury to the lingual nerve when extracting mandibular teeth. A common practice after exposing the tooth is to section it to facilitate removal. The tooth is typically sectioned 3/4 of the way toward the lingual aspect using the surgical handpiece and bur, and the remaining union is split using an elevator. The surgical bur is placed parallel to the buccal groove in impacted molars.

The 1st step in extracting an impacted tooth involves identifying the surgical site. Then, the patient should be placed in an appropriate position in the surgical chair to optimize visualization of the surgical site. A bite block and, if necessary, an appropriate throat screen may be placed to prevent aspiration, depending on the surgeon's judgment. A Weider retractor may be used to retract the tongue, and a Minnesota retractor may be used to retract the cheek and expose the area. A local anesthetic is then injected in appropriate regions. The patient must be adequately anesthetized before the first incisions are made.

Using a 15-blade and a periosteal elevator, a sulcular incision is created with appropriate releasing incisions to raise a subperiosteal flap of adequate size to allow visualization, access, and delivery of the tooth. When creating a flap for extracting a 3rd molar, a distal release incision toward the lingual aspect of the mandible should be avoided, as the lingual nerve may lie on the alveolar bone in this location.[33]

If the tooth is not visualized upon flap reflection, a surgical handpiece with a round or straight tapered fissure bur should be used to remove bone, uncover the tooth, and create a trough around the crown of the tooth to the level of the cementoenamel junction. When using the surgical handpiece, care should be taken not to damage neighboring tooth roots or, in the 3rd molar site, the lingual plate, as the lingual nerve may be in direct contact with the lingual plate in this area. Copious irrigation is also needed when using the surgical handpiece to prevent overheating the bone and removal of debris in the surgical site, as temperatures above 47 °C could cause irreversible osteonecrosis.[34]

At this point, a surgical elevator may be used to attempt delivery of the tooth. However, the adjacent teeth must not be used as a fulcrum to prevent damage to these teeth.

If attempts are unsuccessful, the surgeon may either remove more bone or section the crown or roots of the tooth. When sectioning the roots of a molar, an attempt should be made to cut parallel to the long access of the tooth at the buccal groove. The tooth may be sectioned 3/4 of the way through, keeping the bur parallel, and the remaining 1/4 should be fractured by placing and twisting a thick surgical elevator in the cut. This technique prevents inadvertently cutting through structures posterior to the tooth, such as the lingual plate of the 3rd molar site.

Upon sectioning the tooth, delivery can be attempted using surgical elevators and forceps. Once the tooth is delivered, the extraction site should be irrigated and visualized for the presence of pathology, tooth fragments, IAN or lingual nerve exposure or injury, lingual plate perforation, damaged tooth roots, significant bleeding, and sinus perforations. In the absence of these complications, the flap may be closed with sutures to achieve primary closure or left open for secondary closure, as evidence is insufficient to prove that the risk of alveolar osteitis, wound infection, or adverse effects increases with either technique.[35]

When alveolar ridge preservation is desired, the socket may be filled with bone grafting material and closed to minimize loss of alveolar ridge volume.[36] At the end of the procedure, gauze is placed at the surgical site, and the patient is instructed to apply pressure until hemostasis is achieved.

Complications

The extraction of unerupted teeth carries a risk of intraoperative and postoperative complications. Frequent issues that can arise during the surgical removal of these teeth are alveolar osteitis, bleeding, nerve injury, root displacement, and OAC.

Alveolar Osteitis

Alveolar osteitis, or a dry socket, is the inflammation of the postextraction socket, which occurs when a blood clot fails to form or is dislodged from the wound. Granulation tissue develops instead, impairing the normal healing process. The exact etiology of alveolar osteitis is unknown, though it is thought to occur due to increased fibrinolytic activity.[37] Common signs of alveolar osteitis include foul taste, malodor, and throbbing pain. This condition is more common in female patients. Associated risk factors include smoking, oral contraceptives, lengthy procedures, inexperienced operators, and premature mouth rinsing.[38] Treatment options include irrigation of the wound site with saline or chlorhexidine, sedative dressing placement, and over-the-counter analgesics. Antibiotics are only indicated for patients presenting with fever or swelling.

Postoperative Bleeding

Postoperative bleeding is a common complication after surgical extraction. When bleeding is suspected, the surgeon should carefully examine the surgical site and determine the source. Direct pressure with a gauze may be sufficient to control simple oozing. Hemostatic agents, such as local anesthesia with vasoconstrictor, silver nitrate, and tranexamic acid rinse, can also promote hemostasis.[39] Redressing the surgical site with a collagen plug or an absorbable gelatin sponge may also be considered.

Nerve Injury

IAN and lingual nerve injury can complicate the extraction of impacted mandibular 3rd molars. Damage to these nerves can result in temporary or permanent paresthesia. Paresthesia is relatively rare but may arise as a temporary condition.[40] A patient with a nerve injury should be closely followed up. Recovery from an IAN injury starts at around 6 to 8 weeks, but full recovery may take up to 2 years.[41] Local anesthesia injection can also cause nerve injuries. Neurotoxicity, rather than direct needle trauma, is believed to contribute more significantly to injection injury.

Root Fragments

When a root fragment or a root tip is left in the socket, retrieval must be attempted if possible. A root tip can be left in the socket if it is less than 5 mm long, the root is embedded in bone, and the tooth involved is not infected. Retained roots require a postoperative image and close follow-up to evaluate healing. Attempting to retrieve a root fragment can displace it to adjacent anatomical landmarks. A mandibular root tip is commonly dislodged to the cancellous bone space, the inferior alveolar canal, or the submandibular space. A maxillary root tip is commonly dislodged to the maxillary sinus and the infratemporal fossa.[42]

If displacement is suspected, a CBCT must be obtained to determine its size and location. The retrieval may be delayed if the root cannot be visualized.[43]

OAC is a common complication associated with the extraction of impacted maxillary molars. The most significant risk factor for developing this condition is the proximity of a tooth apex to the antral floor or the presence of maxillary roots projecting into the maxillary sinus.[44] No intervention is needed in small perforations of less than 2 mm. Perforations of 2 to 6 mm can be closed with a collagen plug or resorbable collagen membrane. A buccal or a palatal advancement flap may be used if a large perforation with a defect greater than 6 mm in size is discovered. Antibiotics and nasal decongestants may be prescribed if a patient presents with signs and symptoms of acute or chronic sinusitis.

Clinical Significance

Surgical extraction of unerupted or impacted teeth is a common dentoalveolar procedure performed by various dental specialties. Like most other surgical procedures, extraction is irreversible. Therefore, a surgeon must have proper knowledge of anatomy and pathophysiology and the appropriate skills to extract teeth. The surgeon must also be prepared to manage complications. A comprehensive evaluation is necessary before surgery, followed by the development of a surgical plan that reflects the patient's specific therapeutic goals. The surgeon must also be able to provide risks, benefits, and alternatives to proposed surgical plans to help patients make informed decisions.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Delivering patient-centered care for patients with impacted teeth often necessitates collaboration among various healthcare professionals, including physicians, orthodontists, and prosthodontists, as well as anesthesiologists for cases requiring general anesthesia. Consulting with relevant physicians is essential for patients with medical comorbidities.

In elective extractions, surgery may be postponed until the risk of complications is minimized, giving time for medical management. Coordination with anesthesiologists is critical in complex cases requiring general anesthesia. Case selection and treatment planning for patients with impacted teeth frequently involve orthodontists and prosthodontists.

Since orthodontists and prosthodontists oversee the patient’s ongoing care after the extraction, maintaining regular communication among all professionals is vital. This collaborative approach ensures that treatment decisions are well-informed and the best patient outcomes are achieved.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Grover PS, Lorton L. The incidence of unerupted permanent teeth and related clinical cases. Oral surgery, oral medicine, and oral pathology. 1985 Apr:59(4):420-5 [PubMed PMID: 3858781]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTecco S, Lacarbonara M, Dinoi MT, Gallusi G, Marchetti E, Mummolo S, Campanella V, Marzo G. The retrieval of unerupted teeth in pedodontics: two case reports. Journal of medical case reports. 2014 Oct 9:8():334. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-8-334. Epub 2014 Oct 9 [PubMed PMID: 25301242]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJain P, Rathee M. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Tooth Eruption. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31751068]

Msagati F, Simon EN, Owibingire S. Pattern of occurrence and treatment of impacted teeth at the Muhimbili National Hospital, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. BMC oral health. 2013 Aug 6:13():37. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-13-37. Epub 2013 Aug 6 [PubMed PMID: 23914842]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBayar GR, Ortakoglu K, Sencimen M. Multiple impacted teeth: report of 3 cases. European journal of dentistry. 2008 Jan:2(1):73-8 [PubMed PMID: 19212513]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJaroń A, Trybek G. The Pattern of Mandibular Third Molar Impaction and Assessment of Surgery Difficulty: A Retrospective Study of Radiographs in East Baltic Population. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2021 Jun 3:18(11):. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18116016. Epub 2021 Jun 3 [PubMed PMID: 34205078]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWilliams M,Tollervey D, Lower third molar surgery - consent and coronectomy. British dental journal. 2016 Mar 25; [PubMed PMID: 27012340]

Rood JP, Shehab BA. The radiological prediction of inferior alveolar nerve injury during third molar surgery. The British journal of oral & maxillofacial surgery. 1990 Feb:28(1):20-5 [PubMed PMID: 2322523]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMuhsin H, Brizuela M. Oral Surgery, Extraction of Mandibular Third Molars. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 36508551]

Nguyen JD, Duong H. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Mental Nerve. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31536237]

Pogrel MA, Smith R, Ahani R. Innervation of the mandibular incisors by the mental nerve. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 1997 Sep:55(9):961-3 [PubMed PMID: 9294506]

Çorumlu U, Kopuz C, Aydar Y. Branching Patterns of Mental Nerve in Newborns. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2020 Oct:31(7):2025-2028. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000006611. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32569042]

do Nascimento EH, Dos Anjos Pontual ML, Dos Anjos Pontual A, da Cruz Perez DE, Figueiroa JN, Frazão MA, Ramos-Perez FM. Assessment of the anterior loop of the mandibular canal: A study using cone-beam computed tomography. Imaging science in dentistry. 2016 Jun:46(2):69-75. doi: 10.5624/isd.2016.46.2.69. Epub 2016 Jun 23 [PubMed PMID: 27358813]

Pelé A, Berry PA, Evanno C, Jordana F. Evaluation of Mental Foramen with Cone Beam Computed Tomography: A Systematic Review of Literature. Radiology research and practice. 2021:2021():8897275. doi: 10.1155/2021/8897275. Epub 2021 Jan 6 [PubMed PMID: 33505723]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLin SXY, Sim PR, Lai WMC, Lu JX, Chew JRJ, Wong RCW. Mapping out the surgical anatomy of the lingual nerve: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the Korean Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 2023 Aug 31:49(4):171-183. doi: 10.5125/jkaoms.2023.49.4.171. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37641899]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceOstrowski P, Bonczar M, Wilk J, Michalczak M, Czaja J, Niziolek M, Sienkiewicz J, Szczepanek E, Chmielewski P, Iskra T, Gregorczyk-Maga I, Walocha J, Koziej M. The complete anatomy of the lingual nerve: A meta-analysis with implications for oral and maxillofacial surgery. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2023 Sep:36(6):905-914. doi: 10.1002/ca.24033. Epub 2023 Mar 9 [PubMed PMID: 36864652]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBehnia H, Kheradvar A, Shahrokhi M. An anatomic study of the lingual nerve in the third molar region. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 2000 Jun:58(6):649-51; discussion 652-3 [PubMed PMID: 10847287]

Danesh-Sani SA, Loomer PM, Wallace SS. A comprehensive clinical review of maxillary sinus floor elevation: anatomy, techniques, biomaterials and complications. The British journal of oral & maxillofacial surgery. 2016 Sep:54(7):724-30. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2016.05.008. Epub 2016 May 25 [PubMed PMID: 27235382]

Ghaeminia H, Nienhuijs ME, Toedtling V, Perry J, Tummers M, Hoppenreijs TJ, Van der Sanden WJ, Mettes TG. Surgical removal versus retention for the management of asymptomatic disease-free impacted wisdom teeth. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2020 May 4:5(5):CD003879. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003879.pub5. Epub 2020 May 4 [PubMed PMID: 32368796]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHounsome J, Pilkington G, Mahon J, Boland A, Beale S, Kotas E, Renton T, Dickson R. Prophylactic removal of impacted mandibular third molars: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health technology assessment (Winchester, England). 2020 Jun:24(30):1-116. doi: 10.3310/hta24300. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32589125]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSarica I, Derindag G, Kurtuldu E, Naralan ME, Caglayan F. A retrospective study: Do all impacted teeth cause pathology? Nigerian journal of clinical practice. 2019 Apr:22(4):527-533. doi: 10.4103/njcp.njcp_563_18. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30975958]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePick L, Bauer J. [Dentistry and epilepsy]. Der Nervenarzt. 2001 Dec:72(12):946-9 [PubMed PMID: 11789440]

Chaudhry S, Jaiswal R, Sachdeva S. Dental considerations in cardiovascular patients: A practical perspective. Indian heart journal. 2016 Jul-Aug:68(4):572-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2015.11.034. Epub 2016 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 27543484]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceThornhill MH, Gibson TB, Yoon F, Dayer MJ, Prendergast BD, Lockhart PB, O'Gara PT, Baddour LM. Antibiotic Prophylaxis Against Infective Endocarditis Before Invasive Dental Procedures. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2022 Sep 13:80(11):1029-1041. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.06.030. Epub 2022 Aug 17 [PubMed PMID: 35987887]

Rodríguez Martínez S, Talaván Serna J, Silvestre FJ. [Dental management in patients with cirrhosis]. Gastroenterologia y hepatologia. 2016 Mar:39(3):224-32. doi: 10.1016/j.gastrohep.2015.07.005. Epub 2015 Nov 2 [PubMed PMID: 26541210]

Carter G, Goss AN, Lloyd J, Tocchetti R. Current concepts of the management of dental extractions for patients taking warfarin. Australian dental journal. 2003 Jun:48(2):89-96; quiz 138 [PubMed PMID: 14649397]

Chronopoulos A, Zarra T, Ehrenfeld M, Otto S. Osteoradionecrosis of the jaws: definition, epidemiology, staging and clinical and radiological findings. A concise review. International dental journal. 2018 Feb:68(1):22-30. doi: 10.1111/idj.12318. Epub 2017 Jun 25 [PubMed PMID: 28649774]

Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Aghaloo T, Carlson ER, Ward BB, Kademani D. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons' Position Paper on Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaws-2022 Update. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 2022 May:80(5):920-943. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2022.02.008. Epub 2022 Feb 21 [PubMed PMID: 35300956]

Nicolatou-Galitis O, Schiødt M, Mendes RA, Ripamonti C, Hope S, Drudge-Coates L, Niepel D, Van den Wyngaert T. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: definition and best practice for prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology and oral radiology. 2019 Feb:127(2):117-135. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2018.09.008. Epub 2018 Oct 9 [PubMed PMID: 30393090]

Bansal H. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: An update. National journal of maxillofacial surgery. 2022 Jan-Apr:13(1):5-10. doi: 10.4103/njms.NJMS_236_20. Epub 2022 Apr 20 [PubMed PMID: 35911799]

Martin A, Perinetti G, Costantinides F, Maglione M. Coronectomy as a surgical approach to impacted mandibular third molars: a systematic review. Head & face medicine. 2015 Apr 10:11():9. doi: 10.1186/s13005-015-0068-7. Epub 2015 Apr 10 [PubMed PMID: 25890111]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceJephcott A. The surgical management of the oral soft tissues: 1. Flap design. Dental update. 2007 Oct:34(8):518-20, 522 [PubMed PMID: 18019490]

Pippi R, Spota A, Santoro M. Prevention of Lingual Nerve Injury in Third Molar Surgery: Literature Review. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 2017 May:75(5):890-900. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2016.12.040. Epub 2017 Jan 4 [PubMed PMID: 28142010]

Augustin G, Davila S, Mihoci K, Udiljak T, Vedrina DS, Antabak A. Thermal osteonecrosis and bone drilling parameters revisited. Archives of orthopaedic and trauma surgery. 2008 Jan:128(1):71-7 [PubMed PMID: 17762937]

Bailey E, Kashbour W, Shah N, Worthington HV, Renton TF, Coulthard P. Surgical techniques for the removal of mandibular wisdom teeth. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2020 Jul 26:7(7):CD004345. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004345.pub3. Epub 2020 Jul 26 [PubMed PMID: 32712962]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAvila-Ortiz G, Elangovan S, Kramer KW, Blanchette D, Dawson DV. Effect of alveolar ridge preservation after tooth extraction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of dental research. 2014 Oct:93(10):950-8. doi: 10.1177/0022034514541127. Epub 2014 Jun 25 [PubMed PMID: 24966231]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNitzan DW. On the genesis of "dry socket". Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 1983 Nov:41(11):706-10 [PubMed PMID: 6579255]

Sweet JB, Butler DP. The relationship of smoking to localized osteitis. Journal of oral surgery (American Dental Association : 1965). 1979 Oct:37(10):732-5 [PubMed PMID: 289736]

Jaiswal P, Agrawal R, Gandhi A, Jain A, Kumar A, Rela R. Managing Anticoagulant Patients Undergoing Dental Extraction by using Hemostatic Agent: Tranexamic Acid Mouthrinse. Journal of pharmacy & bioallied sciences. 2021 Jun:13(Suppl 1):S469-S472. doi: 10.4103/jpbs.JPBS_639_20. Epub 2021 Jun 5 [PubMed PMID: 34447136]

Sarikov R, Juodzbalys G. Inferior alveolar nerve injury after mandibular third molar extraction: a literature review. Journal of oral & maxillofacial research. 2014 Oct-Dec:5(4):e1. doi: 10.5037/jomr.2014.5401. Epub 2014 Dec 29 [PubMed PMID: 25635208]

Bhat P, Cariappa KM. Inferior alveolar nerve deficits and recovery following surgical removal of impacted mandibular third molars. Journal of maxillofacial and oral surgery. 2012 Sep:11(3):304-8. doi: 10.1007/s12663-012-0335-0. Epub 2012 Feb 19 [PubMed PMID: 23997481]

Oishi S, Ishida Y, Matsumura T, Kita S, Sakaguchi-Kuma T, Imamura T, Ikeda Y, Kawabe A, Okuzawa M, Ono T. A cone-beam computed tomographic assessment of the proximity of the maxillary canine and posterior teeth to the maxillary sinus floor: Lessons from 4778 roots. American journal of orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics : official publication of the American Association of Orthodontists, its constituent societies, and the American Board of Orthodontics. 2020 Jun:157(6):792-802. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2019.06.018. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32487309]

Jolly SS, Rattan V, Rai SK. Intraoral management of displaced root into submandibular space under local anaesthesia -A case report and review of literature. The Saudi dental journal. 2014 Oct:26(4):181-4. doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2014.05.004. Epub 2014 Jul 15 [PubMed PMID: 25382952]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKhandelwal P, Hajira N. Management of Oro-antral Communication and Fistula: Various Surgical Options. World journal of plastic surgery. 2017 Jan:6(1):3-8 [PubMed PMID: 28289607]