Introduction

Physical and chemical lesions of the oral cavity are frequently identified during routine examinations, as the oral cavity is continuously subjected to trauma and chemical agents. Oral cavity lesions can result from various etiologies, including traumatic occlusion, sharp occlusal anatomy, acidic and alkaline substances or medications, thermal or chemical exposures, and improper oral habits, such as using poorly fitted dentures and displaying parafunctional activities.[1]

The evolution of these lesions varies, with some resolving spontaneously following removal of the irritant. Others may progress to chronic conditions requiring medical intervention. Prompt identification and removal of the offending agent are critical to prevent further tissue damage and facilitate healing. Management generally involves addressing the underlying cause, symptomatic treatment with topical or systemic medications, and, in some cases, surgical intervention to remove persistent lesions or promote healing. This activity examines the most common oral mucosal lesions caused by physical or chemical trauma, including traumatic fibroma, traumatic ulcerative granuloma with stromal eosinophilia, inflammatory papillary hyperplasia, thermal injury, and chemical burns, such as aspirin-induced oral lesions.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Traumatic fibromas are hyperplastic, tumor-like lesions that develop in response to local trauma or irritation. These growths belong to a group of lesions known as reactive hyperplastic lesions of the oral cavity. Traumatic fibromas typically occur in the buccal mucosa and tongue, which are repetitively subjected to trauma, specifically occlusal trauma.[2] Reactive hyperplastic lesions of the oral cavity may also be found on the gingiva.[3]

Traumatic ulcerative granulomas with stromal eosinophilia (TUGSE) are very rare, benign, longstanding ulcerative lesions that arise from mucosal trauma. These growths resemble lymphomas clinically and morphologically due to their sudden onset and delayed healing.[4]

Inflammatory papillary hyperplasia is a benign lesion that develops almost exclusively in the palate of denture wearers.[5] Although rare, this condition has also been described in nondenture wearers and mandibles. Inflammatory papillary hyperplasia is generally classified as a type of denture stomatitis resulting from poor oral hygiene beneath an existing denture, denture misalignment, or continuous use of dentures throughout the day and night.[6]

Thermal injuries result from direct oral mucosal contact with foods and liquids at extreme temperatures, either high or low. Accidental ingestion of hot substances, such as microwaved food, which is normally overheated, is a common cause of thermal injuries.[7]

Aspirin-induced oral lesions are chemical burns caused by placing acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) directly on the oral mucosa to alleviate pain. Aspirin induces the coagulation of proteins and is acidic, burning the surrounding mucosa when applied topically.

Epidemiology

Traumatic fibromas can occur in any patient population. However, these benign growths have a predilection for middle-aged women.[8] A retrospective epidemiological analysis of benign tumors and tumor-like lesions in the maxillofacial region, including the oral cavity, by Sonkodi et al found that 32.4% of the 14,661 biopsies analyzed over 54 years were traumatic fibromas, making them the most prevalent lesions in the study.[9]

TUGSE can occur in any patient population but has a slight predilection for women in the 6th and 7th decades of life.[10] In infants, the presence of natal teeth at birth can lead to tongue ulceration, known as Riga Fede disease, a variant of TUGSE.[11] Kanumuri found the incidence of neonatal teeth at birth to range from 1 in 2,000 to 1 in 3,500 births, highlighting the high likelihood of TUGSE in infants.[12]

Inflammatory papillary hyperplasia primarily affects patients with removable dental prostheses, though some case reports suggest it may also occur in dentate individuals.[13] A 2017 study by Gual-Vaqués et al identified the prevalence of inflammatory papillary hyperplasia at 4.4% among denture wearers, with ill-fitting dentures and smoking as the leading risk factors for its development.

Thermal injury to the oral mucosa is a frequent finding and can occur in any patient population, with no gender or age predilection. Aspirin-induced oral lesions can affect any cohort with access to aspirin. Chemical injury to the oral mucosa is common and has no gender predilection.

Pathophysiology

Traumatic fibromas develop due to local irritation or injury, leading to progressive fibrosis as the tissue attempts to protect itself. An inflammatory infiltrate, localized ulceration, or edema may accompany this process.

TUGSE arises from severe chronic irritation or trauma. The deep ulcerations provoke a strong eosinophilic response, with the cytotoxic byproducts of these cells causing mucosal degeneration and lesion formation.

The pathogenesis of inflammatory papillary hyperplasia remains unclear, but it is likely triggered by poor oral hygiene, leading to Candida infiltration and an inflammatory response beneath a denture. Prolonged denture contact with the tissue further exacerbates this inflammatory reaction.

Thermal injury results from exposure to extreme temperatures, damaging the tissue. Consequently, the epithelium sloughs and the highly vascularized connective tissue is exposed, contributing to the erythematous appearance.

Chemical burns occur due to the cytotoxic effects of alkaline and acidic substances, which disrupt tissue integrity. As necrosis develops, the tissue sloughs off, exposing highly vascularized connective tissue, which results from the heightened inflammatory response in the affected area.

Histopathology

Traumatic fibromas histologically exhibit stratified squamous epithelium, often with hyperkeratosis, overlying dense fibrous connective tissue. TUGSE typically shows granulomatous tissue extending deeply into the mucosal layers.[14] Heavy inflammatory infiltrates, including numerous eosinophils, are observed, along with small lymphocytes, histiocytes, and large lymphoid cells.

Histologically, inflammatory papillary hyperplasia is characterized by epithelial hyperplasia with papillary projections, accompanied by varying degrees of subepithelial chronic inflammation and fibrosis. Thermal injuries and chemical burns are typically diagnosed based on patient history and generally resolve before a biopsy becomes necessary.

History and Physical

Traumatic fibromas present with varying clinical features but are always preceded by localized irritation or trauma. These lesions typically appear as smooth, nodular, sessile growths up to 2 cm in diameter.[15] Traumatic fibromas are firm, usually match the color of the surrounding oral mucosa, and have well-defined borders, occasionally accompanied by a traumatic ulcer (see Image. Traumatic Fibroma).[16]

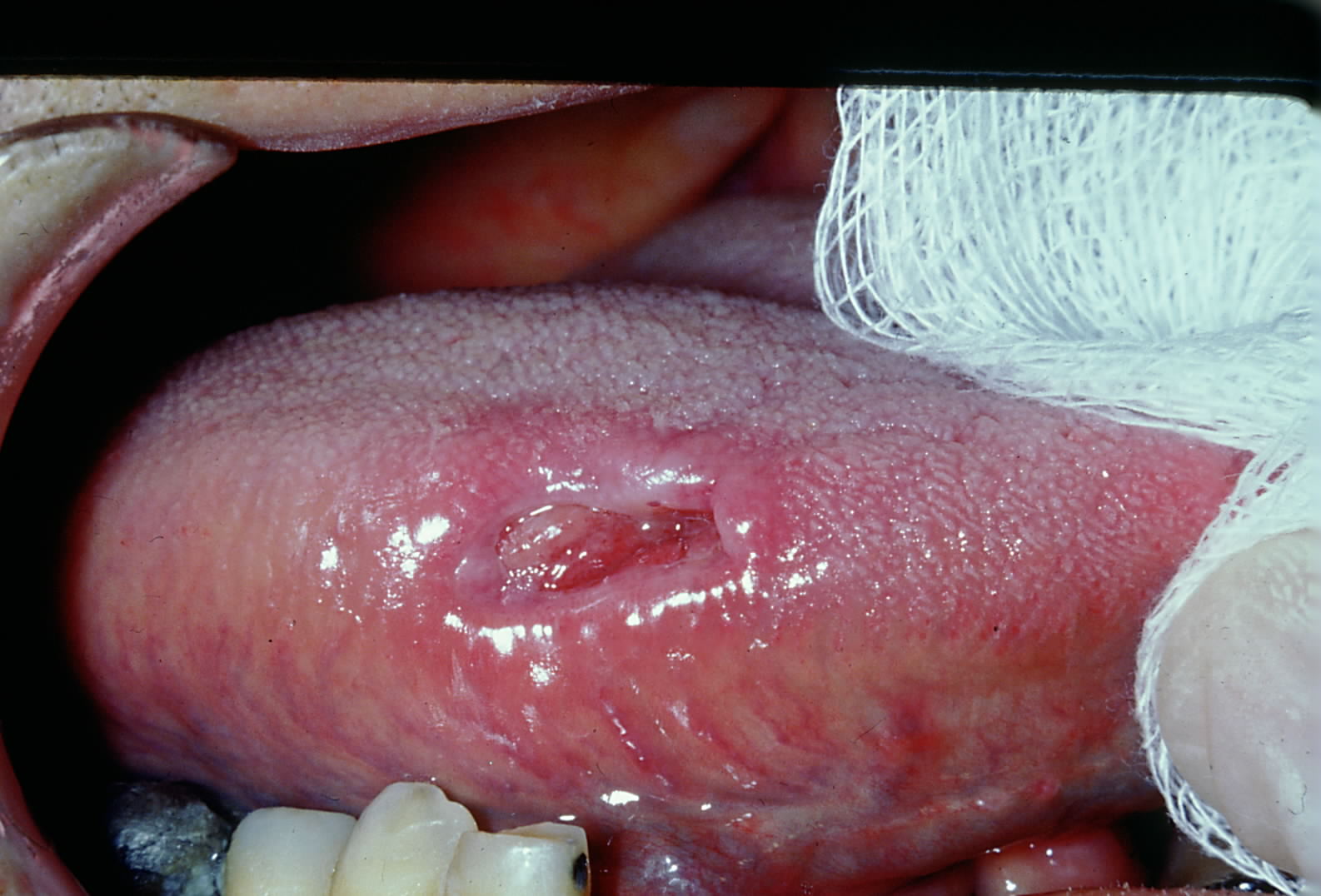

TUGSE typically presents as a self-limiting, solitary ulceration with a fibrinopurulent membrane and elevated, indurated margins (see Image. Traumatic Ulcerative Granuloma with Stromal Eosinophilia).[17][18] These lesions may resemble squamous cell carcinoma, warranting a biopsy.[19][20]

Inflammatory papillary hyperplasia manifests as small, reddened, concentric papillomas on the hard palate. These lesions are often described as "mulberry-like" in form, with their number and appearance varying depending on the degree of inflammation (see Image. Inflammatory Papillary Hyperplasia).

Thermal injuries typically present with localized or diffuse tissue damage.[21] Depending on the severity, these lesions may manifest as ulcerations or erosions on the affected tissues, usually appearing pink to red with an ulcerated or diffuse border (see Image. Thermal Burn).

Aspirin-induced oral lesions present as ulcerated, aphthous-like white lesions and are triggered by an immune response to aspirin's acidic components. The tissue surrounding the lesion often sloughs off, leaving localized erythema (see Image. Aspirin-Induced Chemical Burn).

Evaluation

Histological analysis is used to diagnose traumatic fibromas definitively. Findings typically include hyperplastic and hyperkeratotic epithelium overlying dense fibrous tissue.

TUGSE can mimic several malignant conditions and should, therefore, be biopsied if the lesion persists for 2 weeks after any irritants are removed.[22] Histologically, these lesions exhibit ulcerated epithelium with a fibrinopurulent exudate over an inflamed stroma.[23] A granulomatous infiltrate rich in lymphocytes, histiocytes, and eosinophils is also often observed.

Inflammatory papillary hyperplasia may present as a few or multiple lesions requiring evaluation. A detailed history of denture care is essential to identify potential causative factors, including the duration of denture wear, with particular emphasis on nighttime use, frequency, and the patient’s denture hygiene practices. The prosthesis should also be assessed for proper fit.

Thermal injuries should be evaluated through patient history to determine the lesion's etiology. Aspirin-induced oral lesions require evaluation based on the patient's history to identify the underlying cause, as mucosal sloughing may mimic autoimmune or malignant processes.

Treatment / Management

Traumatic fibromas are typically removed by excisional biopsy and enucleation to prevent recurrence. This procedure is ideally performed under local anesthesia. Identifying and eliminating the source of irritation can further reduce the likelihood of recurrence.[24](B3)

TUGSE may be treated with antibiotics to reduce the microbial load on the lesion surface.[25] The lesion should be closely monitored, and any etiologic traumatic agents, such as malocclusion, sharp cusps on teeth, and local irritants, should be addressed. If the lesion does not resolve within 2 weeks, a biopsy is necessary for a definitive diagnosis. In infants, neonatal teeth may be smoothed or reshaped under local anesthesia if indicated.

Inflammatory papillary hyperplasia may not require treatment in some cases, while others may necessitate surgical excision of the inflamed papillary tissue. Additionally, relining, rebasing, or fabricating a new removable dental prosthesis may be indicated.

Thermal injuries are generally self-limiting and will resolve with protection from further trauma or exposure to extreme temperatures. Palliative treatments, such as topical benzocaine cream or petroleum jelly, can be used to protect the ulcerated mucosa. While no standardized treatment has been established for intraoral burns, managing inflammation or pain is always recommended.

Aspirin-induced oral lesions are a form of chemical burn that, like other chemical burns, typically require only local palliative measures for healing.[26] The key aspect of treatment and management is patient education, emphasizing that aspirin provides analgesia only when ingested, not when applied to the mucosa.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for physical and chemical oral mucosal lesions includes a variety of conditions with overlapping clinical presentations. Early and correct diagnosis not only helps in managing symptoms but also prevents complications due to misdiagnosis.

Traumatic Fibroma

- Any benign mesenchymal tumor (lipoma, neuroma, neurilemmoma)

- Pyogenic granuloma

- Peripheral ossifying fibroma, if on the gingiva

Traumatic Ulcer

- Recurrent aphthous ulcer

- Herpetic ulceration

- Traumatic eosinophilic granuloma

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Ulcerative mucosal disease, e.g., lichen planus

Inflammatory Papillary Hyperplasia

- Secondary pseudomembranous candidiasis

- HPV-associated papillary lesions

- Erythema migrans

Thermal Injury

- Recurrent aphthous ulcer

- Herpes simplex virus

- Behçet’s disease

Aspirin-Induced Oral Lesions

- TUGSE

- Traumatic ulceration

- Recurrent aphthous ulcer

Prognosis

Traumatic fibromas have an excellent prognosis, as they comprise a reactive overgrowth of normal tissue. Recurrence is rare with appropriate surgical excision and removal of the irritant.[27] TUGSE also has a favorable prognosis, as the lesion is self-limiting and typically does not require aggressive treatment.[28] However, recurrence of the lesion or a traumatic ulcer is likely if the offending agent is not removed.

Inflammatory papillary hyperplasia generally has a good prognosis. Discontinuing the use of ill-fitting dentures and allowing sufficient time for tissue healing can lead to the resolution of the condition.[29] Patient education is essential to reduce the risk of recurrence, emphasizing the need for daily denture removal to facilitate proper cleansing and allow rest for the oral tissues.

Thermal injuries also have an excellent prognosis, as the oral mucosa is highly resilient and typically heals on its own, provided no further thermal exposure occurs. Aspirin-induced oral lesions typically have a favorable prognosis, with healing occurring once the aspirin is removed from the tissue. However, recurrence depends on the patient discontinuing the practice of placing aspirin on the mucosa.

Complications

Traumatic fibromas typically arise from parafunctional habits, such as chewing the cheek or tongue, along with local irritants and trauma.[30] Without addressing these habits or sources of trauma, traumatic fibromas are likely to recur. Since these lesions are generally treated through surgical excision, encouraging the patient to maintain optimal oral hygiene is essential to promoting healing.

TUGSE can present as a painful lesion that shares many features with squamous cell carcinoma. Therefore, lesions that do not resolve within 2 weeks of removing the etiologic agent should be biopsied for a definitive diagnosis. The management of Riga Fede disease in infants can be challenging and should involve referral to a pediatric dentist.

Inflammatory papillary hyperplasia does not carry malignant potential but can be mistaken for a potentially malignant process.[31] Patients with this condition should be encouraged to allow proper healing time for their oral tissues. Treatment is highly patient-dependent, as meticulous oral hygiene is essential for resolution.

Thermal injuries are typically painful and may be further irritated by the patient’s tongue or other oral tissues. Patients should be advised to minimize additional trauma to the area.

Aspirin-induced oral lesions are painful and may worsen if the habit persists. Therefore, patients should be encouraged to minimize further trauma to the area.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Traumatic fibromas should be brought to the patient’s attention once identified and biopsied for a definitive diagnosis. Patients should be informed of the potential causes of these lesions.

TUGSE is a self-limiting condition that requires immediate attention, as it is a reactive inflammatory process that can mimic malignant conditions. Patients should be counseled on parafunctional habits or potential local irritants that may increase the risk of recurrence.

Inflammatory papillary hyperplasia is most commonly observed in patients who leave their dentures in place overnight. Patients should be instructed to take off their removable dental prosthesis for 6 to 8 hours each day to properly clean the oral tissues and relieve the pressure that the prosthesis may exert.

Thermal injuries may be prevented through patient education and compliance. Patients should be encouraged to ensure that foods and liquids are at a safe temperature before consumption to avoid potential harm to the oral tissues.

Aspirin-induced oral lesions typically resolve once the patient discontinues use. Patients should be educated on the ineffectiveness of placing aspirin directly on the oral mucosa, as it does not provide analgesia and can instead cause damage and pain.

Pearls and Other Issues

Though not exhaustive, the information presented in this activity provides the practitioner with a baseline understanding of the possible etiologies and tools for differentiating between common physical and chemical lesions of the oral mucosa. A biopsy must be performed if a lesion is suspected to be malignant or if the etiology cannot be determined.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Physical and chemical lesions of the oral mucosa are common and should be managed by an interprofessional healthcare team. Identifying the lesion's etiology is crucial in determining the appropriate treatment. If the etiology remains unclear or the lesion persists for more than 2 weeks, a referral to a specialist for further diagnostic evaluation is recommended. Each team member plays a vital role in promptly identifying these lesions, initiating treatment, making referrals, and providing patient education to ensure optimal care. This collaborative approach contributes to improved patient outcomes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

da Silveira Teixeira D, de Figueiredo MAZ, Cherubini K, de Oliveira SD, Salum FG. The topical effect of chlorhexidine and povidone-iodine in the repair of oral wounds. A review. Stomatologija. 2019:21(2):35-41 [PubMed PMID: 32108654]

Panta P. Traumatic fibroma. The Pan African medical journal. 2015:21():220. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2015.21.220.7498. Epub 2015 Jul 27 [PubMed PMID: 26448815]

Sangle VA, Pooja VK, Holani A, Shah N, Chaudhary M, Khanapure S. Reactive hyperplastic lesions of the oral cavity: A retrospective survey study and literature review. Indian journal of dental research : official publication of Indian Society for Dental Research. 2018 Jan-Feb:29(1):61-66. doi: 10.4103/ijdr.IJDR_599_16. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29442089]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWright KT, Pozdnyakova O. Say hello to TUGSE! Blood. 2019 Oct 17:134(16):1360. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019002505. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31698439]

Gual-Vaqués P, Jané-Salas E, Egido-Moreno S, Ayuso-Montero R, Marí-Roig A, López-López J. Inflammatory papillary hyperplasia: A systematic review. Medicina oral, patologia oral y cirugia bucal. 2017 Jan 1:22(1):e36-e42 [PubMed PMID: 27918740]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTucker KM, Heget HS. The incidence of inflammatory papillary hyperplasia. Journal of the American Dental Association (1939). 1976 Sep:93(3):610-3 [PubMed PMID: 1066391]

Kang S, Kufta K, Sollecito TP, Panchal N. A treatment algorithm for the management of intraoral burns: A narrative review. Burns : journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 2018 Aug:44(5):1065-1076. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2017.09.006. Epub 2017 Oct 9 [PubMed PMID: 29032979]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZarei MR, Chamani G, Amanpoor S. Reactive hyperplasia of the oral cavity in Kerman province, Iran: a review of 172 cases. The British journal of oral & maxillofacial surgery. 2007 Jun:45(4):288-92 [PubMed PMID: 17097201]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSonkodi I, Boda K, Decsi G, Buzás K, Nagy K. [A clinicopathological retrospective epidemiological analysis of benign tumors and tumor-like lesions in the oral and maxillofacial region, diagnosed at the University of Szeged, Department of Oral Medicine (1960-2014)]. Orvosi hetilap. 2018 Sep:159(37):1516-1524. doi: 10.1556/650.2018.31164. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30196718]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSethi A, Banga A, Raja R, Raina R. Traumatic ulcerative granuloma with stromal eosinophilia. Indian journal of dental research : official publication of Indian Society for Dental Research. 2020 Jul-Aug:31(4):636-639. doi: 10.4103/ijdr.IJDR_330_18. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33107469]

Costacurta M, Maturo P, Docimo R. Riga-Fede disease and neonatal teeth. ORAL & implantology. 2012 Jan:5(1):26-30 [PubMed PMID: 23285403]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKanumuri PK. Riga Fede Disease. Journal of neonatal surgery. 2017 Jan-Mar:6(1):20. doi: 10.21699/jns.v6i1.475. Epub 2017 Jan 1 [PubMed PMID: 28083506]

Gual-Vaqués P, Jané-Salas E, Marí-Roig A, López-López J. Inflammatory Papillary Hyperplasia in a Non-Denture-Wearing Patient: A Case History Report. The International journal of prosthodontics. 2017 Jan/Feb:30(1):80-82. doi: 10.11607/ijp.4955. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28085987]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBenitez B, Mülli J, Tzankov A, Kunz C. Traumatic ulcerative granuloma with stromal eosinophilia - clinical case report, literature review, and differential diagnosis. World journal of surgical oncology. 2019 Nov 9:17(1):184. doi: 10.1186/s12957-019-1736-z. Epub 2019 Nov 9 [PubMed PMID: 31706333]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceValério RA, de Queiroz AM, Romualdo PC, Brentegani LG, de Paula-Silva FW. Mucocele and fibroma: treatment and clinical features for differential diagnosis. Brazilian dental journal. 2013 Sep-Oct:24(5):537-41. doi: 10.1590/0103-6440201301838. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24474300]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJiang M, Bu W, Chen X, Gu H. A case of irritation fibroma. Postepy dermatologii i alergologii. 2019 Feb:36(1):125-126. doi: 10.5114/ada.2019.82834. Epub 2019 Feb 22 [PubMed PMID: 30858793]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSharma B, Koshy G, Kapoor S. Traumatic Ulcerative Granuloma with Stromal Eosinophila: A Case Report and Review of Pathogenesis. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR. 2016 Oct:10(10):ZD07-ZD09 [PubMed PMID: 27891480]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMarszałek A, Neska-Długosz I. Traumatic ulcerative granuloma with stromal eosinophilia. A case report and short literature review. Polish journal of pathology : official journal of the Polish Society of Pathologists. 2011 Sep:62(3):172-5 [PubMed PMID: 22102076]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSarangarajan R, Vaishnavi Vedam VK, Sivadas G, Sarangarajan A, Meera S. Traumatic ulcerative granuloma with stromal eosinophilia - Mystery of pathogenesis revisited. Journal of pharmacy & bioallied sciences. 2015 Aug:7(Suppl 2):S420-3. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.163474. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26538890]

Banerjee A, Misra SR, Kumar V, Mohanty N. Traumatic ulcerative granuloma with stromal eosinophilia (TUGSE): a rare self-healing oral mucosal lesion. BMJ case reports. 2021 Aug 13:14(8):. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2021-245097. Epub 2021 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 34389602]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKannan S, Chandrasekaran B, Muthusamy S, Sidhu P, Suresh N. Thermal burn of palate in an elderly diabetic patient. Gerodontology. 2014 Jun:31(2):149-52. doi: 10.1111/ger.12010. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24797620]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTaghi A, Motamedi MH. Riga-Fede disease: a histological study and case report. Indian journal of dental research : official publication of Indian Society for Dental Research. 2009 Apr-Jun:20(2):227-9. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.52893. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19553727]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChandra S, Raju S, Sah K, Anand P. Traumatic ulcerative granuloma with stromal eosinophilia. Archives of Iranian medicine. 2014 Jan:17(1):91-4 [PubMed PMID: 24444070]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFerrer Angelini C, Salvà Siquier A, Pallarés García H, Baselga Torres E. [Fibroma due to irritation]. Anales de pediatria (Barcelona, Spain : 2003). 2012 Jun:76(6):377-8. doi: 10.1016/j.anpedi.2012.01.023. Epub 2012 Mar 8 [PubMed PMID: 22406160]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChavan SS, Reddy P. Traumatic ulcerative eosinophillic granuloma with stromal eosinophilia of tongue. South Asian journal of cancer. 2013 Jul:2(3):144. doi: 10.4103/2278-330X.114128. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24455596]

Jolly M. White lesions of the mouth. International journal of dermatology. 1977 Nov:16(9):713-25 [PubMed PMID: 336562]

Babu B, Hallikeri K. Reactive lesions of oral cavity: A retrospective study of 659 cases. Journal of Indian Society of Periodontology. 2017 Jul-Aug:21(4):258-263. doi: 10.4103/jisp.jisp_103_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29456298]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceShen WR, Chang JY, Wu YC, Cheng SJ, Chen HM, Wang YP. Oral traumatic ulcerative granuloma with stromal eosinophilia: A clinicopathological study of 34 cases. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association = Taiwan yi zhi. 2015 Sep:114(9):881-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2013.09.012. Epub 2013 Oct 23 [PubMed PMID: 24269143]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFISHER AK, RASHID PJ. Inflammatory papillary hyperplasia of the palatal mucosa. Oral surgery, oral medicine, and oral pathology. 1952 Feb:5(2):191-8 [PubMed PMID: 14891213]

Gonsalves WC, Chi AC, Neville BW. Common oral lesions: Part II. Masses and neoplasia. American family physician. 2007 Feb 15:75(4):509-12 [PubMed PMID: 17323711]

Bhaskar SN, Beasley JD, Cutright DE. Inflammatory papillary hyperplasia of the oral mucosa: report of 341 cases. Journal of the American Dental Association (1939). 1970 Oct:81(4):949-52 [PubMed PMID: 4917113]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence