Introduction

Activities of daily living (ADLs) refer to the basic skills necessary for individuals to independently care for themselves, such as eating, bathing, and mobility. The term was first coined by Sidney Katz in 1950.[1][2] ADLs is used as an indicator of a person's functional status. The inability to perform ADLs leads to a patient's dependence on others or assistive devices, significantly increasing their risk of adverse health outcomes. The inability to perform essential ADLs may lead to unsafe living conditions and a poor quality of life. Assessing an individual's ability to perform ADLs is crucial, as these are predictors of admission to nursing homes, the need for alternative living arrangements, hospitalization, and paid home care. The outcome of a treatment program can also be assessed by reviewing a patient's ADLs.[3][4][5][6]

Nurses are often the first members of the interprofessional team to recognize a decline in a patient's functional status during hospitalization; therefore, routine screening of ADLs is essential, and nursing assessments of ADLs should be conducted for all hospitalized patients. Hospitalization for an acute or chronic illness can impact a person's ability to achieve personal goals and maintain independent living. Chronic diseases progress over time, resulting in a physical decline that may lead to a loss of ability to perform ADLs. In 2011, the United States National Health Interview Survey found that 20.7% of adults aged 85 or older, 7% of those aged 75 to 84, and 3.4% of those aged 65 to 74 required assistance with ADLs.[7][8]

Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Function

Types of Activities of Daily Living

ADLs are classified into basic and instrumental ADLs. Basic ADLs or physical ADLs are skills required to manage one's basic physical needs, including personal hygiene and grooming, dressing, toileting, transferring or ambulating, and eating. In contrast, instrumental ADLs include more complex activities related to living independently in the community. These activities include managing finances and medications, preparing food, performing housekeeping tasks, and doing laundry.

Basic Activities of Daily Living: The basic ADLs include the following:

- Ambulating: The Extent of an individual's ability to move from 1 position to another and walk independently.

- Feeding: The Ability of an individual to feed oneself.

- Dressing: The ability to select appropriate clothes and to put them on.

- Personal hygiene: The ability to bathe and groom oneself and maintain dental hygiene, nail, and hair care.

- Continence: The ability to control bladder and bowel function.

- Toileting: The ability to get to and from the toilet, use it appropriately, and clean oneself afterward.

Assessing an individual's ability to complete each ADL can help determine whether a patient needs daily assistance. The assessment can also help older individuals and those with disabilities determine their eligibility for state and federal assistance programs.

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living: Instrumental ADLs require more complex thinking skills, including organizational skills. These activities are as follows:

- Transportation: The ability to plan for and manage transportation, either by driving or by organizing other means of transport.

- Managing finances: The ability to pay bills and manage financial assets.

- Shopping: The ability to organize and be aware of needed items and procure them, such as maintaining adequate groceries in the home for sustenance or shopping for necessary clothing and other products.

- Meal preparation: The ability to manage everything required to prepare a meal, including safely operating cooking devices and food storage needs.

- Housecleaning and home maintenance: The ability to clean dishes after eating, maintain living areas in a reasonably clean and tidy state, and keep up with home maintenance.

- Managing communication with others: The ability to manage telephone and mail.

- Managing medications: The ability to obtain medications and take them correctly as directed.

As individuals age and their functional status declines, they often need assistance with instrumental ADLs before requiring assistance with basic ADLs. Assisting with instrumental ADLs can be a more intermittent task than assisting with basic ADLs.[9]

Causes for Limitations in Activities of Daily Living

Decline or impairment in physical function can arise from various conditions. Aging is a natural process that often leads to a decline in the functional status of patients and is a common cause of progressive loss of ADLs.[10] Musculoskeletal, neurological, circulatory, or sensory conditions can lead to decreased physical function and impairment in ADLs.[11] A cognitive or mental decline can also lead to impaired ADLs.[12] Severe cognitive fluctuations in patients with dementia have a significant association with impaired engagement in ADLs that negatively affect their quality of life. Impairment in instrumental ADLs often leads to social isolation, which can lead to worsening cognition, general health, and mood. Other factors, such as adverse effects of medications or the patient's home environment, can influence the ability to perform ADLs. Acute injuries can suddenly reduce an individual's ability to perform ADLs. The severity of the injury and the patient's prior health status ultimately determine their capacity for compensation or the level of dependence on others.[13][14]

Hospitalization and acute illnesses have also been associated with a decline in ADLs. Sands et al reported that loss of ADL functioning over 1 year is independently associated with acute hospital admission for acute illness and cognitive impairment among frail older adults.[15] Similarly, Cinvinsky et al performed a prospective observational study that evaluated the changes in ADL function occurring before and after hospital admission. They found that many hospitalized older individuals are discharged with ADL functions that are worse than their baseline function.[16]

Assessment of Activities of Daily Living

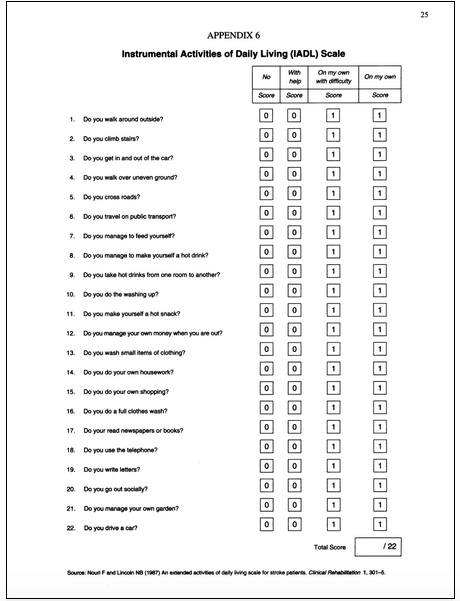

Defining the extent of loss of basic and instrumental ADLs is crucial for defining and providing appropriate care and support. Several checklists have been developed by various entities. Although there is some consensus on what ADLs should be included, there is significant variability in how these questionnaires ask about ADL skills.[17][18]

The most frequently used checklists include the Katz Index of Independence in ADL and the Lawton Instrumental ADL Scale. The Katz scale assesses basic ADLs but does not assess instrumental ADLs. The Katz ADL scale is sensitive to changes in declining health status; however, it is limited in its ability to measure small increments of change observed during the rehabilitation of older adults. Despite this, the Katz scale is highly useful in establishing a common language for healthcare providers involved in overall care and discharge planning regarding patient function.[1][19][1]

The Lawton Instrumental ADL Scale is used to evaluate independent living skills and is most useful for identifying fluctuations in a person's improvement or deterioration over time. The scale assesses 8 functional domains—food preparation, housekeeping, telephone use, transportation, medication management, finance management, shopping, and laundry. Individuals are scored based on their highest level of functioning in each category. The overall score ranges from 0, indicating low functioning and dependence, to 8, indicating high functioning and independence. The scale is an easy-to-administer assessment instrument that provides self-reported information about functional skills necessary to live in the community. Specific deficits identified can help nurses and other interprofessional team members plan for safe patient discharge. The limitations of this scale are that it is a self-administered test rather than an observation of actual demonstration of the functional task. This limitation may lead to overestimation or underestimation of the ability to perform the activity.[20][21]

The Kohlman Evaluation of Living Skills is a tool that uses observation of task performance and self-reported data. This provision makes it more appropriate for use in patients with cognitive decline or dementia, as their self-reported abilities are often inaccurate. This evaluation specifically assesses 17 individual skills, categorized into 5 assessment categories—ADL, cognition, life participation, occupational performance, and communication.[22]

Clinical Significance

The assessment of ADLs is an essential aspect of routine patient assessment. The information assists the interdisciplinary team in assessing the patient's status, prognosis, and treatment plan.[4] An ADL assessment helps determine whether a patient requires further rehabilitation, home assistance, or a safer environment such as a skilled nursing or long-term care facility. The inability to ambulate may increase the risk of falls. Falls are associated with an increased mortality rate. Individuals aged 65 or older who experience recurrent falls often have a poor prognosis after a fall. Such falls and subsequent hospitalization also burden healthcare utilization and costs.[23]

Other important factors to consider before transitioning a patient from independent living to assisted living or a nursing home include their ability to prepare meals, maintain household cleanliness, shop, use public transportation, or drive.[24] The impact of a loss of ADL on the patient should be recognized. Independent living is highly encouraged and advocated in American society, and many aging individuals fear losing their autonomy.[24][25]

Occupational therapists conduct ADL assessments to determine benefits for disability insurance and long-term care insurance policies. The cost of home care, skilled care, assisted living, and nursing homes is a concern for many families. Not all supportive care is covered by Medicare or private insurance, resulting in financial concerns for patients and their caregivers. The high cost of care may lead to decisions that preclude patients from receiving the necessary support for ADLs.[26]

Access to care is also a significant concern, as individuals from lower socioeconomic backgrounds or disadvantaged groups often face challenges in obtaining quality care for older adults. Access can be difficult due to transportation, distance, and availability.[27] Although many placements in care facilities are short-term, most patients stay longer than a year if they are unable to perform more than 2 of 6 ADLs.[28]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Although many healthcare professionals can assess ADLs, clinicians, advanced practice providers, nurses, occupational therapists, and physical therapists are most commonly involved in these evaluations. Effective communication among team members is critical for safe discharge planning and ongoing care support. Patients who are unable to perform ADLs may require rehabilitation services or in-home assistance. Impairments such as difficulty dressing or toileting can lead to poor hygiene and a reduced quality of life. Difficulty ambulating or transferring increases the risk of falls and social isolation, potentially leading to further complications. An inability to eat independently can result in malnutrition, dehydration, and further decline. Referrals to occupational therapists, physical therapists, and dietitians should be made as appropriate.

Routine assessment of functionality should be standard practice for patients of all ages. An interprofessional team that communicates and collaborates effectively ensures optimal patient evaluation, discharge planning, and follow-up care. Nursing staff should promptly report ADL concerns to the medical team, and the broader clinical team should coordinate with home health and social work services to provide necessary support. Home health nursing staff must monitor for any deterioration in ADLs and communicate changes to the clinical team. Accurate ADL assessment is crucial for ensuring patient safety, effective care planning, qualification for paid services, and efficient healthcare cost management.[5][29]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

The implications and significance of changes in a patient's ADLs vary among the different stakeholders involved in the patient’s care, including the following:

- Case managers, nurses, and social workers

- Primary care clinicians

- Home health or skilled nursing agencies

- Physical and occupational therapists

- Long-term care insurance providers

- Government agencies

Nurses and care managers assess and collect information on a person's ability to perform ADLs. The data enable them to plan for each individual's continuum of care. Clinicians use these assessments to formulate and develop a care plan, which is then provided to the home health agency or skilled nursing agencies. These agencies then select the appropriate staff needed for each client. Physical and occupational therapists work according to the care plan and document the patient's progress in ADLs to ensure that rehabilitation goals are achieved to the greatest possible extent. Insurance providers and government agencies use ADL assessments to determine the patient's qualifications and pay for the services rendered.[5][30]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

Nurses and occupational therapists assess basic and instrumental ADLs daily in all hospitalized patients. Accurate assessment, planning, intervention, and evaluation of ADLs can be the deciding factor between a patient maintaining independence or requiring daily assistance.

Although various tools are available for use during daily shift assessments, nurses should be aware of each patient's specific needs for assistance with ADLs. When a patient is at risk for a change in ADLs, nurses should assist the patient and report to interprofessional team members to establish a new care plan.

Possible nursing diagnoses recognized by the North American Nursing Diagnosis Association International include altered health maintenance, defined as a state in which an individual lacks sufficient physiological or psychological energy to resist or complete required or desired daily activities. Other possible nursing diagnoses include risk of injury, activity intolerance, social isolation, or ineffective family coping.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Katz S. Assessing self-maintenance: activities of daily living, mobility, and instrumental activities of daily living. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1983 Dec:31(12):721-7 [PubMed PMID: 6418786]

Bieńkiewicz MM, Brandi ML, Goldenberg G, Hughes CM, Hermsdörfer J. The tool in the brain: apraxia in ADL. Behavioral and neurological correlates of apraxia in daily living. Frontiers in psychology. 2014:5():353. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00353. Epub 2014 Apr 23 [PubMed PMID: 24795685]

Guidet B, de Lange DW, Boumendil A, Leaver S, Watson X, Boulanger C, Szczeklik W, Artigas A, Morandi A, Andersen F, Zafeiridis T, Jung C, Moreno R, Walther S, Oeyen S, Schefold JC, Cecconi M, Marsh B, Joannidis M, Nalapko Y, Elhadi M, Fjølner J, Flaatten H, VIP2 study group. The contribution of frailty, cognition, activity of daily life and comorbidities on outcome in acutely admitted patients over 80 years in European ICUs: the VIP2 study. Intensive care medicine. 2020 Jan:46(1):57-69. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05853-1. Epub 2019 Nov 29 [PubMed PMID: 31784798]

Costenoble A, Knoop V, Vermeiren S, Vella RA, Debain A, Rossi G, Bautmans I, Verté D, Gorus E, De Vriendt P. A Comprehensive Overview of Activities of Daily Living in Existing Frailty Instruments: A Systematic Literature Search. The Gerontologist. 2021 Apr 3:61(3):e12-e22. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnz147. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31872238]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCagle JG, Lee J, Ornstein KA, Guralnik JM. Hospice Utilization in the United States: A Prospective Cohort Study Comparing Cancer and Noncancer Deaths. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2020 Apr:68(4):783-793. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16294. Epub 2019 Dec 27 [PubMed PMID: 31880312]

Rosenberg T, Montgomery P, Hay V, Lattimer R. Using frailty and quality of life measures in clinical care of the elderly in Canada to predict death, nursing home transfer and hospitalisation - the frailty and ageing cohort study. BMJ open. 2019 Nov 12:9(11):e032712. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032712. Epub 2019 Nov 12 [PubMed PMID: 31722953]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWolff JL, Feder J, Schulz R. Supporting Family Caregivers of Older Americans. The New England journal of medicine. 2016 Dec 29:375(26):2513-2515. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1612351. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28029922]

Adams PF, Kirzinger WK, Martinez ME. Summary health statistics for the u.s. Population: national health interview survey, 2011. Vital and health statistics. Series 10, Data from the National Health Survey. 2012 Dec:(255):1-110 [PubMed PMID: 25116371]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCahn-Weiner DA, Boyle PA, Malloy PF. Tests of executive function predict instrumental activities of daily living in community-dwelling older individuals. Applied neuropsychology. 2002:9(3):187-91 [PubMed PMID: 12584085]

Geriatric Medicine Research Collaborative. Delirium is prevalent in older hospital inpatients and associated with adverse outcomes: results of a prospective multi-centre study on World Delirium Awareness Day. BMC medicine. 2019 Dec 14:17(1):229. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1458-7. Epub 2019 Dec 14 [PubMed PMID: 31837711]

Wang LY, Chen HX, Zhu H, Hu ZY, Zhou CF, Hu XY. Physical activity as a predictor of activities of daily living in older adults: a longitudinal study in China. Frontiers in public health. 2024:12():1444119. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1444119. Epub 2024 Oct 25 [PubMed PMID: 39525460]

Farias ST, Park LQ, Harvey DJ, Simon C, Reed BR, Carmichael O, Mungas D. Everyday cognition in older adults: associations with neuropsychological performance and structural brain imaging. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society : JINS. 2013 Apr:19(4):430-41. doi: 10.1017/S1355617712001609. Epub 2013 Feb 1 [PubMed PMID: 23369894]

Farias ST, Harrell E, Neumann C, Houtz A. The relationship between neuropsychological performance and daily functioning in individuals with Alzheimer's disease: ecological validity of neuropsychological tests. Archives of clinical neuropsychology : the official journal of the National Academy of Neuropsychologists. 2003 Aug:18(6):655-72 [PubMed PMID: 14591439]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChu NM, Sison S, Muzaale AD, Haugen CE, Garonzik-Wang JM, Brennan DC, Norman SP, Segev DL, McAdams-DeMarco M. Functional independence, access to kidney transplantation and waitlist mortality. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2020 May 1:35(5):870-877. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfz265. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31860087]

Sands LP, Yaffe K, Lui LY, Stewart A, Eng C, Covinsky K. The effects of acute illness on ADL decline over 1 year in frail older adults with and without cognitive impairment. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2002 Jul:57(7):M449-54 [PubMed PMID: 12084807]

Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, Counsell SR, Stewart AL, Kresevic D, Burant CJ, Landefeld CS. Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003 Apr:51(4):451-8 [PubMed PMID: 12657063]

Desai AK, Grossberg GT, Sheth DN. Activities of daily living in patients with dementia: clinical relevance, methods of assessment and effects of treatment. CNS drugs. 2004:18(13):853-75 [PubMed PMID: 15521790]

Fields JA, Machulda M, Aakre J, Ivnik RJ, Boeve BF, Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Smith GE. Utility of the DRS for predicting problems in day-to-day functioning. The Clinical neuropsychologist. 2010 Oct:24(7):1167-80. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2010.514865. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20924981]

Katz S, Downs TD, Cash HR, Grotz RC. Progress in development of the index of ADL. The Gerontologist. 1970 Spring:10(1):20-30 [PubMed PMID: 5420677]

Graf C. The Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) Scale. Medsurg nursing : official journal of the Academy of Medical-Surgical Nurses. 2009 Sep-Oct:18(5):315-6 [PubMed PMID: 19927971]

Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. The Gerontologist. 1969 Autumn:9(3):179-86 [PubMed PMID: 5349366]

Burnett J, Dyer CB, Naik AD. Convergent validation of the Kohlman Evaluation of Living Skills as a screening tool of older adults' ability to live safely and independently in the community. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2009 Nov:90(11):1948-52. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.05.021. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19887222]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWong MM, Pang PF. Factors Associated with Falls in Psychogeriatric Inpatients and Comparison of Two Fall Risk Assessment Tools. East Asian archives of psychiatry : official journal of the Hong Kong College of Psychiatrists = Dong Ya jing shen ke xue zhi : Xianggang jing shen ke yi xue yuan qi kan. 2019 Mar:29(1):10-14 [PubMed PMID: 31237251]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceVaughan L, Leng X, La Monte MJ, Tindle HA, Cochrane BB, Shumaker SA. Functional Independence in Late-Life: Maintaining Physical Functioning in Older Adulthood Predicts Daily Life Function after Age 80. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2016 Mar:71 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S79-86. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glv061. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26858328]

Warmoth K, Tarrant M, Abraham C, Lang IA. Relationship between perceptions of ageing and frailty in English older adults. Psychology, health & medicine. 2018 Apr:23(4):465-474. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2017.1349325. Epub 2017 Jul 4 [PubMed PMID: 28675053]

Damukaitis C, Schirm V. Program planning for long-term care: meeting the demand for nursing services. Nursing homes and senior citizen care. 1989 Nov:38(3):23-4 [PubMed PMID: 10296792]

Gorges RJ, Sanghavi P, Konetzka RT. A National Examination Of Long-Term Care Setting, Outcomes, And Disparities Among Elderly Dual Eligibles. Health affairs (Project Hope). 2019 Jul:38(7):1110-1118. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05409. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31260370]

Abrahamson K, Hass Z, Arling G. Shall I Stay or Shall I Go? The Choice to Remain in the Nursing Home Among Residents With High Potential for Discharge. Journal of applied gerontology : the official journal of the Southern Gerontological Society. 2020 Aug:39(8):863-870. doi: 10.1177/0733464818807818. Epub 2018 Oct 26 [PubMed PMID: 30366510]

Wang J, Caprio TV, Simning A, Shang J, Conwell Y, Yu F, Li Y. Association Between Home Health Services and Facility Admission in Older Adults With and Without Alzheimer's Disease. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2020 May:21(5):627-633.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.11.002. Epub 2019 Dec 24 [PubMed PMID: 31879184]

Fong JH, Mitchell OS, Koh BS. Disaggregating activities of daily living limitations for predicting nursing home admission. Health services research. 2015 Apr:50(2):560-78. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12235. Epub 2014 Sep 26 [PubMed PMID: 25256014]