Introduction

The Bartholin glands, or greater vestibular glands, are homologs of the bulbourethral glands in the male.[1] They are 2 pea-sized (about 0.5 cm) mucus-secreting glands positioned at the lower posterior sides of the vaginal opening, typically near the 4 o’clock and 8 o’clock positions, that help provide moisture to the vulva and vagina. They drain through ducts that are 2.0 to 2.5 cm long and are located between the labia minora and the hymenal edge.[2] In a healthy state, these glands are typically not palpable during a physical examination.[3]

A Bartholin gland cyst forms when the duct becomes obstructed, allowing fluid to accumulate underneath the skin (see Image. Bartholin Gland Cyst). Cysts and abscesses often occur after the onset of puberty. The incidence decreases after menopause, at which time the risk of malignant transformation must be considered, especially in recurrent or complex cases.[4]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

A Bartholin gland cyst is a benign blockage of the Bartholin gland that is usually unilateral, asymptomatic, and may be incidentally found during a pelvic exam or imaging study. Bartholin gland obstruction may occur after trauma to the area, episiotomy, or childbirth; however, it usually occurs without an identifiable cause.[5] One causative theory is that ductal obstruction is due to friction during sexual intercourse.[1] Bartholin cyst formation is the most common complication after surgical treatment for provoked vulvodynia, including procedures, eg, perineoplasty, vestibuloplasty, and various forms of vestibulectomy (eg, simplified, modified, posterior, or radical), with an incidence of up to 9%.[6]

Epidemiology

Bartholin cysts and abscesses most commonly occur in individuals of childbearing age. Symptomatic cases account for about 2% of all gynecologic visits each year. An abscess can develop without a preceding cyst, and abscesses are approximately 3 times more common than cysts. A cyst does not always precede an abscess.[7][8] Bartholin gland carcinoma is extremely rare and accounts for less than 2% of vulvar cancers, usually diagnosed after menopause.[2]

Pathophysiology

A Bartholin cyst forms when the duct of the Bartholin gland becomes obstructed, preventing normal drainage of glandular secretions. This leads to fluid accumulation. A Bartholin cyst is usually 2 to 4 cm in diameter and may cause dyspareunia, urinary irritation, and vague pelvic pain or pressure. When bacteria enter the blocked duct, the cyst can become infected, forming an abscess. These abscesses are usually polymicrobial, containing normal vaginal and cervical flora, eg, Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and Escherichia coli.[8]

History and Physical

When taking a history from a patient with a suspected Bartholin gland cyst or abscess, clinicians should inquire about the duration of symptoms, tenderness with activities, eg, walking, sitting, standing, or sexual intercourse, presence of purulent drainage, a history of previous Bartholin gland cyst or abscess, vaginal bleeding or discharge, and sexually transmitted infections.

The physical exam will often reveal asymmetry with a protrusion of 1 side (left or right) of the inferior aspect of the vulva and vagina. Bartholin gland abscesses, unlike Bartholin cysts, are very painful. While both are primarily unilateral, Bartholin abscesses are often tender to palpation, erythematous, indurated, and may have an area of fluctuance or purulent drainage.[8] Bartholin cysts frequently have a prolonged course, as they are typically asymptomatic. Malignancy, while rare, may have a similar presentation and is most commonly a squamous cell carcinoma.[2]

Evaluation

Bartholin cysts and abscesses do not frequently require further laboratory or radiographic studies; however, wound cultures and biopsy may be performed during incision and drainage of an abscess. If sexually transmitted infections are suspected, then a full sexually transmitted infection screen should be considered and appropriate treatment initiated.

If malignancy is suspected due to an atypical presentation of the mass or if the patient is older than 40, then a biopsy should be considered.[9] In 1897, diagnostic criteria were developed for Bartholin gland cancer. They were later revised by Chamlian and Taylor in 1972 and include the following 3 criteria

- The lesion involves the area of the Bartholin gland and is histologically compatible with the origin from the organ.

- Pathological examination shows transition areas from normal to neoplastic elements.

- No evidence of other primary tumors as an etiology of the malignancy is noted.[2]

Treatment / Management

The size of the cyst, the patient´s age, and history of recurrence are all factored in to determine the appropriate management of a Bartholin cyst. Asymptomatic Bartholin cysts do not require treatment. Bartholin cysts or abscesses that are spontaneously draining may be managed conservatively with sitz baths and analgesics. With incision and drainage only, high recurrence rates are unacceptably high. Therefore, this is not recommended for treatment.[10]

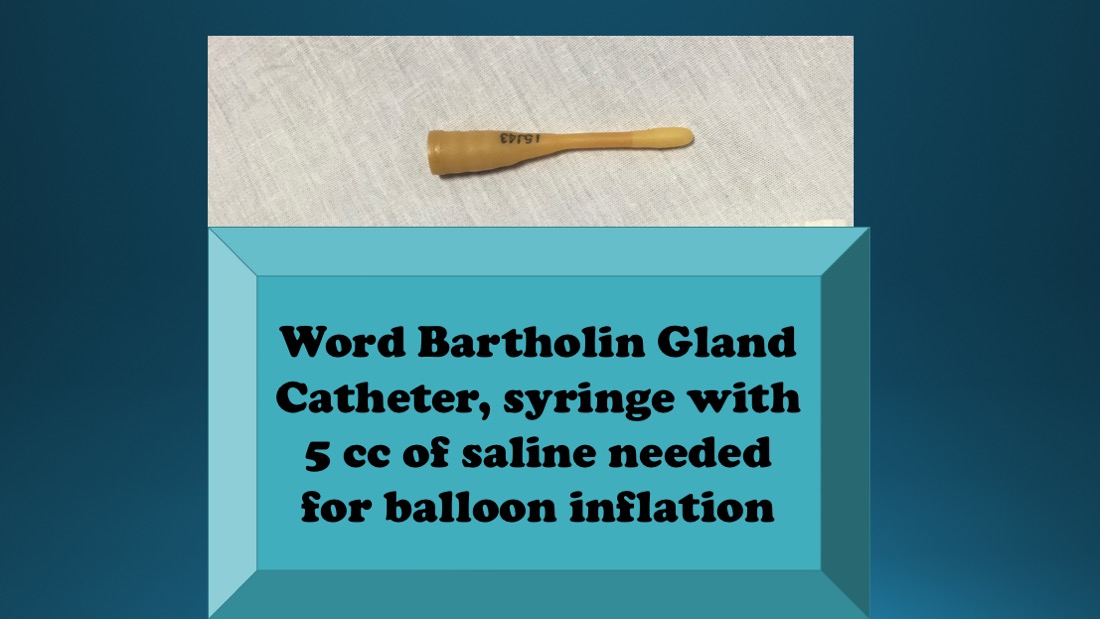

No one method of treatment is superior to any other in terms of recurrence rates.[11] First-time Bartholin abscesses or symptomatic cysts may be treated with incision and drainage with Word catheter placement due to the ease and effectiveness of this treatment. The Word catheter, first introduced in 1968, is commonly used in the United States and Europe to treat symptomatic Bartholin cysts or abscesses. Word catheters are a small, 5.5 cm silicone tube with an inflatable balloon on the end. The catheter is placed into the cyst or abscess to allow continued drainage and help form a new duct, reducing the need for surgery. The procedure is simple, quick, and can be done in an office setting. In Germany, the usual treatment is marsupialization, typically done under general anesthesia, as the use of the Word catheter is uncommon and not widely practiced.[1](A1)

Catheter Drainage Therapy

Incision and drainage with a Word catheter are performed by first cleaning the region with povidone-iodine and anesthetizing the location where the incision will be made with at least 3 mL of 1% lidocaine. A small, approximately 3 to 5 mm, vertical stab incision should be made with a #11 scalpel along the mucosal surface of the labia minora to avoid noticeable scarring and to reduce the risk of Word catheter displacement (see Image. Bartholin Gland Word Catheter). Purulent discharge evacuated may be sent to the lab for cultures, and a biopsy may also be performed at this time. The Word catheter is then inserted with the balloon tip sitting within the abscess cavity. The balloon tip is inflated with 3 to 5 mL of saline. For comfort and to reduce the chance of displacement, the external portion of the Word catheter is tucked into the vagina. Word catheters should be left in place for at least 4 weeks for appropriate drainage and tract epithelialization.[12] Patients do not need to follow any activity restrictions, including sexual activity.

Placing a Word catheter can present challenges. A small incision may make insertion difficult, while a larger incision increases the risk of the catheter dislodging prematurely. Additionally, patients may experience discomfort if the catheter balloon is inflated excessively.[13]

A similar procedure may be used to treat a symptomatic Bartholin cyst or abscess, especially in resource-poor settings. This involves the use of a Jacobi ring, a ring made from butterfly needle tubing and suture. The tubing is threaded with an approximately 20-cm length of 2-0 silk suture. The Jacobi ring enters and exits the abscess through 2 separate incisions. When the suture ends are tied, a closed rubber ring is formed.[13] In this technique, a small incision is made on the mucosal surface of the abscess to allow lysis of adhesions and drainage. A Kelly forceps is then inserted into the cavity, where a second small incision is created. The forceps are used to thread one end of the Jacobi ring, a 5-cm segment of butterfly venipuncture tubing, through the abscess or cyst cavity. An absorbable suture previously placed within the lumen is tied at both ends to form a loop or ring. Unlike balloon catheters, this method has a lower risk of early dislodgment and better patient satisfaction. The tube can remain in place for 4 to 6 weeks. Removal is simple and involves cutting the suture and withdrawing the tubing.

Surgical Therapies

Incision and drainage with Word catheter or Jacobi ring placement may be attempted a second time for recurrent Bartholin cysts. Antibiotic therapy should be considered for those who have failed initial incision and drainage with a Word catheter placement, patients with systemic symptoms including fever, patients who have suspected sepsis, and those considered at high risk for recurrence.

Marsupialization is generally used for recurrent cases and is usually performed by a gynecologist in the operating room.[10] Marsupialization is performed by creating a 2-cm incision lateral to the hymenal ring, everting the edges with forceps, and suturing the edges onto the epithelial surface with interrupted absorbable sutures.[14] Treatment with marsupialization is 7 times more costly than treatment with a Word catheter.[14] Other less common procedures include silver nitrate or alcohol sclerotherapy [15][10], carbon dioxide laser vaporization [16], Jacobi ring placement [17], and Bartholin gland excision as a last resort when other modalities have failed.(A1)

Pregnant Patients

Women who are pregnant and have Bartholin abscesses should be treated in the same manner as nonpregnant women, except Bartholin gland excision, which should be avoided if possible due to the increased risk of bleeding.

Differential Diagnosis

Most benign vaginal cysts are embryological remnants or the result of trauma. The Müllerian ducts develop into the fallopian tubes, uterus, cervix, broad ligament, and upper vagina. Normally, the vaginal lining changes to squamous epithelium from the urogenital sinus. However, some Müllerian epithelium may remain along the vaginal wall. As a result, Müllerian cysts can form anywhere in the vagina.[18]

Differential diagnoses of Bartholin cyst include:

- Other cysts (eg, inclusion, Müllerian, or Gartner, Skene, sebaceous, and canal of Nuck)

- Vaginal prolapse

- Vulvar angiomyofibroblastoma

- Endometriosis

- Epidermal inclusion cyst

- Choriocarcinoma

- Myeloid sarcoma

- Leiomyoma

- Myxoid leiomyosarcoma

- Fibroma

- Angiomyxoma

- Adenosis

- Hematoma

- Myoblastoma

- Ischiorectal abscess

- Folliculitis

- Fibroadenoma

- Lipoma

- Papillary hidradenoma

- Syringoma

- Urethral diverticulum

- Adenocarcinoma

- Squamous cell carcinoma

Pertinent Studies and Ongoing Trials

In the WoMan-trial (World Catheter and Marsupialization in Women With a Cyst or Abscess of the Bartholin Gland), a randomized controlled trial in the Netherlands and England between August 2010 and May 2014, 161 women were randomly allocated to treatment by Word catheter or marsupialization to compare the recurrence of a cyst or abscess within 1 year. Recurrence occurred in 10 women (12%) in the Word catheter group and 8 women (10%) in the marsupialization group. Within the first 24 hours after treatment, 33% used analgesics in the Word catheter group versus 74% in the marsupialization group. Time from diagnosis to treatment was 1 hour for placement of Word catheter versus 4 hours for marsupialization. Recurrence rates were found to be comparable within the 2 groups; however, the marsupialization group had increased use of analgesics within the first 24 hours and also had increased duration of treatment.[11]

Treatment Planning

Imaging may be helpful when evaluating a vaginal cyst, and it may help in planning surgical excision, particularly when the etiology or presentation is unclear.[18]

Toxicity and Adverse Effect Management

Placement of the Word catheter is generally described as a painful procedure. But, the catheter is well tolerated thereafter with few adverse effects, including interference with the patient’s sexual activity.[1]

Prognosis

The prognosis of a Bartholin cyst is excellent, but if the cyst is just aspirated, high recurrence rates have been reported. The healing and recurrence rates are similar among fistulization with Word catheter, marsupialization, and silver nitrate and alcohol sclerotherapy. Needle aspiration and incision and drainage, the 2 simplest procedures, are not recommended due to their relatively increased recurrence rate.[19]

Complications

The treatment of Bartholin gland cysts by traditional surgery is characterized by some disadvantages and complications, eg, hemorrhage, postoperative dyspareunia, infections, and the necessity for general anesthesia. CO2 laser surgery may be less invasive.[20]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Sitz baths are recommended for a few days postoperatively. Early ambulation is highly recommended.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Deterrence of Bartholin cysts involves minimizing factors that contribute to duct blockage and infection. Encouraging good perineal hygiene with wiping front to back, avoiding harsh soaps or douching, and wearing breathable cotton underwear can help reduce irritation and bacterial contamination. Safe sexual practices, including the use of barrier protection and limiting the number of sexual partners, may also lower the risk of sexually transmitted infections that can cause gland duct obstruction or abscess formation. Patients should be educated to recognize early symptoms and seek prompt care if swelling, pain, or signs of infection develop. For patients with a history of recurrent cysts, regular sitz baths and early medical attention for any vulvar discomfort may help prevent progression to abscess.

Pearls and Other Issues

Bartholin cysts are usually painless unless they become large or infected, at which point they can present with unilateral vulvar pain, swelling, and difficulty sitting or walking. Asymptomatic cysts can often be managed conservatively with sitz baths and observation, while symptomatic large cysts or abscesses typically require drainage and placement of a Word catheter, with antibiotics reserved for select cases. Distinguishing between a simple cyst, abscess, and potential malignancy is essential, particularly in postmenopausal patients, where any Bartholin mass warrants further evaluation. Common pitfalls include inadequate drainage, failure to place a catheter leading to recurrence, and unnecessary antibiotic use. Prevention strategies focus on maintaining good perineal hygiene, avoiding irritants, practicing safe sex, and seeking early medical care for symptoms. Patients with recurrent cysts should be referred to gynecology for definitive treatment, such as marsupialization or gland excision.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Bartholin gland cysts and abscesses develop when the duct becomes obstructed, preventing normal drainage of glandular secretions. While cysts are often asymptomatic, abscesses cause pain, swelling, and tenderness. Diagnosis relies on history and physical examination, with biopsy indicated in patients older than 40 or with atypical presentations to exclude malignancy. Evidence supports Word catheter or Jacobi ring placement over simple incision and drainage to reduce recurrence and promote healing, with marsupialization or other modalities reserved for recurrent or complex cases.

Effective management requires clinicians to integrate procedural skills, accurate diagnosis, and individualized treatment selection. Physicians, general practitioners, and advanced practitioners must coordinate with nurses for peri-procedural care and patient education, while pharmacists ensure appropriate analgesia and antibiotic stewardship when indicated. Interprofessional communication facilitates timely follow-up, monitoring for recurrence, and escalation for surgical referral when necessary. This collaborative approach improves patient-centered care, optimizes clinical outcomes, enhances safety, and strengthens team performance in managing Bartholin gland disorders.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Psilopatis I, Emons J, Levidou G, Hildebrandt T, Pretscher J, Kehl S. Feasibility and Satisfaction With the Word Catheter in Treatment of Bartholin's Cyst and Abscess. In vivo (Athens, Greece). 2024 May-Jun:38(3):1292-1299. doi: 10.21873/invivo.13568. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38688643]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTuretta C, Mazzeo R, Capalbo G, Miano S, Fruscio R, Di Donato V, Falcone F, Mangili G, Pignata S, Palaia I. Management of primary and recurrent Bartholin's gland carcinoma: A systematic review on behalf of MITO Rare Cancer Group. Tumori. 2024 Apr:110(2):96-108. doi: 10.1177/03008916231208308. Epub 2023 Nov 13 [PubMed PMID: 37953636]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBawankar P, Ankar R. Bartholin gland cyst: a clinical image. The Pan African medical journal. 2022:43():174. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2022.43.174.38017. Epub 2022 Dec 5 [PubMed PMID: 36879636]

Lee WA, Wittler M. Bartholin Gland Cyst. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30335304]

Pundir J, Auld BJ. A review of the management of diseases of the Bartholin's gland. Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology : the journal of the Institute of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2008 Feb:28(2):161-5. doi: 10.1080/01443610801912865. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18393010]

Saçıntı KG, Razeghian H, Bornstein J. Surgical Treatment for Provoked Vulvodynia: A Systematic Review. Journal of lower genital tract disease. 2024 Oct 1:28(4):379-390. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000834. Epub 2024 Aug 6 [PubMed PMID: 39105455]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMarzano DA, Haefner HK. The bartholin gland cyst: past, present, and future. Journal of lower genital tract disease. 2004 Jul:8(3):195-204 [PubMed PMID: 15874863]

Elkins JM, Hamid OS, Simon LV, Sheele JM. Association of Bartholin cysts and abscesses and sexually transmitted infections. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2021 Jun:44():323-327. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.04.027. Epub 2020 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 32321682]

Visco AG, Del Priore G. Postmenopausal bartholin gland enlargement: a hospital-based cancer risk assessment. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1996 Feb:87(2):286-90 [PubMed PMID: 8559540]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLong N, Morris L, Foster K. Bartholin Gland Abscess Diagnosis and Office Management. Primary care. 2021 Dec:48(4):569-582. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2021.07.013. Epub 2021 Oct 14 [PubMed PMID: 34752270]

Kroese JA, van der Velde M, Morssink LP, Zafarmand MH, Geomini P, van Kesteren P, Radder CM, van der Voet LF, Roovers J, Graziosi G, van Baal WM, van Bavel J, Catshoek R, Klinkert ER, Huirne J, Clark TJ, Mol B, Reesink-Peters N. Word catheter and marsupialisation in women with a cyst or abscess of the Bartholin gland (WoMan-trial): a randomised clinical trial. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2017 Jan:124(2):243-249. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14281. Epub 2016 Sep 19 [PubMed PMID: 27640367]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceReif P, Ulrich D, Bjelic-Radisic V, Häusler M, Schnedl-Lamprecht E, Tamussino K. Management of Bartholin's cyst and abscess using the Word catheter: implementation, recurrence rates and costs. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology. 2015 Jul:190():81-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.04.008. Epub 2015 Apr 29 [PubMed PMID: 25963974]

Gennis P, Li SF, Provataris J, Shahabuddin S, Schachtel A, Lee E, Bobby P. Jacobi ring catheter treatment of Bartholin's abscesses. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2005 May:23(3):414-5 [PubMed PMID: 15915435]

JACOBSON P. Vulvovaginal (Bartholin) cyst treatment by marsupialization. Western journal of surgery, obstetrics, and gynecology. 1950 Dec:58(12):704-8 [PubMed PMID: 14798829]

Ozdegirmenci O, Kayikcioglu F, Haberal A. Prospective Randomized Study of Marsupialization versus Silver Nitrate Application in the Management of Bartholin Gland Cysts and Abscesses. Journal of minimally invasive gynecology. 2009 Mar-Apr:16(2):149-52 [PubMed PMID: 19598336]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFambrini M, Penna C, Pieralli A, Fallani MG, Andersson KL, Lozza V, Scarselli G, Marchionni M. Carbon-dioxide laser vaporization of the Bartholin gland cyst: a retrospective analysis on 200 cases. Journal of minimally invasive gynecology. 2008 May-Jun:15(3):327-31. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2008.02.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18439506]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKushnir VA, Mosquera C. Novel technique for management of Bartholin gland cysts and abscesses. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2009 May:36(4):388-90. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2008.05.019. Epub 2008 Nov 26 [PubMed PMID: 19038518]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTrikhacheva A, Dengler K, Murdock TA, Gruber D. Vaginal Bulge is Not Always Prolapse. Journal of minimally invasive gynecology. 2025 Mar:32(3):219. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2024.11.008. Epub 2024 Nov 17 [PubMed PMID: 39551438]

Omole F, Kelsey RC, Phillips K, Cunningham K. Bartholin Duct Cyst and Gland Abscess: Office Management. American family physician. 2019 Jun 15:99(12):760-766 [PubMed PMID: 31194482]

Frega A, Schimberni M, Ralli E, Verrone A, Manzara F, Schimberni M, Nobili F, Caserta D. Complication and recurrence rate in laser CO2 versus traditional surgery in the treatment of Bartholin's gland cyst. Archives of gynecology and obstetrics. 2016 Aug:294(2):303-9. doi: 10.1007/s00404-016-4045-6. Epub 2016 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 26922440]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence