Introduction

Bladder stones are solid calculi primarily found in the urinary bladder. Although bladder stones are often calcified, they may also consist of non-calcific material (see Image. A Bladder Calculus).[1][2][3][4] The incidence of bladder stones is relatively low in Western countries but higher in developing countries, primarily due to dietary factors. The regions most affected include countries in the Middle East, North Africa, Thailand, Indonesia, and Myanmar. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Ultrasound of the Urinary Tract," for more information.

Bladder stones account for about 5% of all urinary stones and usually occur due to urinary stasis, as seen in conditions such as benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) or neurogenic bladder. However, they can also form in healthy individuals without anatomical defects, foreign bodies, strictures, or infections.[5][6] The presence of upper urinary tract calculi does not necessarily increase the risk of bladder stone formation. Bladder stones cause specific symptoms and are a significant source of patient discomfort.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Urinary stasis, such as that seen in BPH or neurogenic bladder disorder, is the primary cause of bladder calculi.[5] Most of these stones are newly formed in the bladder, although some may originate in the kidneys as a calculus or a sloughed papilla. Stones from the kidneys that are small enough to pass through the ureters can easily travel through the urethra unless there is significant bladder dysfunction or outlet obstruction. Stones that remain in the bladder will develop additional concentric layers of material, which may or may not be identical to the original core material.[7][8][9] Bladder outlet obstruction, most commonly due to BPH, is the leading risk factor for bladder stones, accounting for 45% to almost 80% of such cases.[10][11][12][13][14] Among men undergoing surgical treatment for BPH, 3% to 4.7% develop bladder stones.[15][16] Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Cystinuria," for more information.

Any nonabsorbable foreign body left in the bladder that is not spontaneously expelled will eventually develop layers of stone material and form calculus. An example of this would be a surgical staple or permanent suture left exposed inside the bladder. This is why absorbable suture material is recommended for urinary surgeries.

A retained double pigtail stent can also form stone material if left in the urinary tract for a prolonged period. Another example is a fragment from a Foley catheter balloon that "fell out" after a balloon rupture, with a retained fragment left in the bladder. For this reason, it is important to inspect any Foley catheter that has been forcibly extracted or "fallen out" to ensure no balloon fragments are missing, as they could develop into stones. If this inspection is not possible or there is concern about a retained fragment, cystoscopy should be performed to remove any intravesical balloon fragments.

Foley catheters are associated with a higher incidence of bladder stones compared to intermittent catheterization. In a study of patients with spinal cord injuries, 36% developed bladder calculi over an 8-year follow-up period. However, improved urologic care significantly reduced the bladder stone formation rate to approximately 10%.[17]

Radiation therapy, schistosomiasis, bladder augmentation surgery, urethral strictures, neurogenic or hypotonic bladder dysfunction, and bladder diverticula are additional risk factors for bladder stone formation. Up to two-thirds of patients with spinal cord injuries develop bladder stones.[18]

In children, risk factors for bladder stones include chronic or recurrent diarrhea, inadequate hydration, and protein-deficient diets.[19][20][21] Such predisposing conditions are commonly found in developing countries.[19] The most frequent laboratory finding in these children is low urinary volume, followed by hypocitraturia.[21][22][23]

Neurogenic bladder, spinal cord injury, continent urinary diversions, and bladder augmentation surgery are well-established risk factors for bladder stone formation.

- Patients with neurogenic bladder requiring permanent indwelling catheters due to spinal cord injury are 6 times more likely to develop bladder stones than individuals who void normally.[24][25]

- Up to two-thirds of spinal cord–injured patients with neurogenic bladders will experience bladder stone formation.[18]

- The annual recurrence rate of bladder stones in spinal cord–injured patients with neurogenic bladders is 16%.[26]

- Over 20 years, more than 40% of patients with augmented bladders develop stones.[27][28]

- Bladder irrigation performed daily or 3 times weekly has been shown to reduce the incidence of bladder stones in augmented bladders and continent urinary diversions.[29][30][31]

- In contrast, standard ileal conduit surgery is associated with a significantly lower stone formation rate, not exceeding 3%.[31][32]

Epidemiology

The overall incidence of bladder stones in adults appears to be decreasing in developed countries, likely due to the widespread use of BPH medications such as alpha-blockers and 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs).

Bladder stones are more common in males than females, particularly in males aged 50 or older, with a male-to-female prevalence ratio ranging from 4:1 to 10:1.[10] Stones larger than 100 grams in size are rare and predominantly occur in males.[33]

In general, adult men with BPH and bladder stones are more likely to have a history of nephrolithiasis, gout, lower urinary pH, and lower urinary magnesium levels compared to men with BPH who do not have bladder calculi. The presence of urinary tract infections (UTIs) and significant intravesical prostatic extension (BPH) are the clinical signs most strongly associated with the development of bladder calculi.[34]

In children, the overall incidence of bladder stones is also decreasing, primarily due to improved prenatal and postnatal care, as well as a general improvement in neonatal nutritional support. Boys typically have more bladder stones than girls, and these stones are not associated with unrelated urolithiasis. Recurrences of bladder stones are relatively uncommon in children, in contrast to pediatric renal stone disease, where recurrences are more frequent. Most cases of pediatric bladder stones occur in children between the ages of 2 and 5.[35] The peak incidence of bladder stones occurs at age 3 in children and 60 in adults.

Pathophysiology

Uric acid is the most common composition of bladder stones in adults, accounting for about 50% of cases. Most patients with uric acid bladder stones do not have gout or hyperuricemia. Risk factors for uric acid bladder stones include low urinary pH, dehydration, hyperuricosuria, and uric acid nephrolithiasis.

Other substances that can form bladder stones include calcium oxalate, calcium phosphate, ammonium urate, cystine, and calcium-ammonium-magnesium phosphate (also known as triple phosphate or struvite stones, which are always associated with infection). Patients prone to chronic bacteriuria and urinary infections, such as those with spinal cord injuries or severely hypotonic bladders, are more likely to develop struvite (infection-related or triple phosphate) and calcium phosphate stones.[36] Stones composed primarily of calcium oxalate or calcium phosphate typically begin as renal calculi, becoming trapped in the bladder. Over time, they develop additional layers of stone material until they grow too large to pass, causing symptoms in the patient.

Jackstones are a rare form of bladder calculi, visually resembling larger versions of children's jacks, with crossing X-shaped structures joined at a central nidus. They consist of a protein-rich, radiolucent core surrounded by multiple concentric layers of hard calcium oxalate monohydrate. Care must be taken during removal to avoid injuring the patient.[37] An association between bladder calculi and cancer of the urinary bladder has been suggested, although this remains a controversial and unresolved issue.[38][39][40][41]

In children, the most common types of bladder stones are calcium oxalate, calcium phosphate, and possibly ammonium acid urate. In developing countries, infants and young children are often fed only breast milk and rice, which can lead to high urinary ammonia excretion due to low dietary phosphorus. These children also tend to have a high intake of green vegetables (which increases dietary oxalate) and low dietary citrate.[42]

History and Physical

Bladder stones may not present with any specific symptoms or may be asymptomatic. They are typically associated with conditions that cause incomplete bladder emptying, most commonly BPH. Patients may also experience a combination of urinary symptoms such as terminal hematuria, suprapubic pain, weak stream, dysuria, and more. Terminal gross hematuria with sudden cessation of voiding is a common sign of a large bladder calculus. Bladder stones can also cause urinary incontinence, dysuria, vesicovaginal fistulas, and outflow obstruction.[43][44][45][46][47] About 66% of adult patients with bladder stones, particularly those with larger calculi (>4 cm), will experience overactive bladder symptoms. However, in some cases, the only symptom may be recurrent UTIs.[13][48]

Pain may be present at the tip of the penis or anywhere in the scrotum, pelvis, or perineum. In some cases, a distended bladder may be palpable, but the stone itself is typically not. Due to the vague nature of the signs and symptoms, a definitive diagnosis usually requires cystoscopy or imaging.

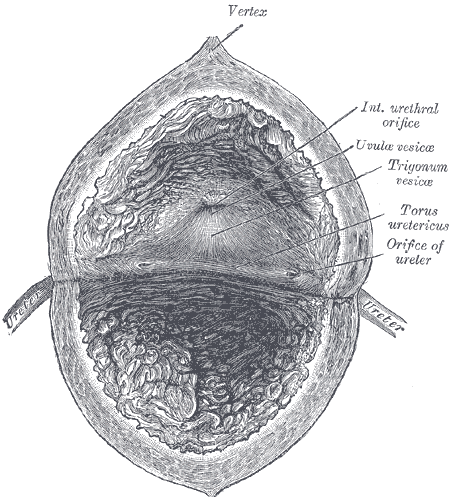

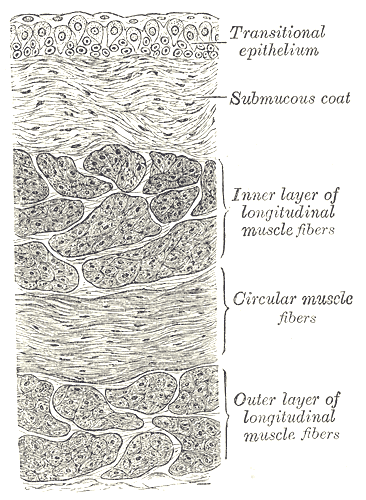

In the past, a definitive diagnosis was sometimes made by passing a Van Buren sound. When the sound made contact with a bladder stone, it would produce a "click" sound along with a transmitted vibration. Even today, "sounding" refers to the exploration of a bodily cavity with a solid probe to detect abnormalities by touch, feel, or sound. However, this technique is now of historical interest only and is no longer used clinically, as modern imaging technology and flexible cystoscopy are more commonly available (see Images. Interior Anatomy of the Urinary Bladder and Vertical Section of the Urinary Bladder Wall).

Evaluation

Urinalysis in affected individuals may reveal blood, nitrites, or leukocytes, as well as a low urinary pH and signs of a UTI. A plain x-ray or KUB (kidney, ureter, and bladder) x-ray is often the first diagnostic study ordered, but in adult men, the stone may not be calcified (eg, uric acid stones), making plain x-rays insufficient. Computed tomography (CT) or bladder ultrasound can reliably detect bladder stones, with stones typically appearing as hyperechoic areas with shadowing on ultrasound. Cystoscopy can confirm the diagnosis (see Image. Computed Tomography Scan of the Pelvis).

Ammonium urate is radiolucent but may develop a calcific coating, which makes it visible on x-rays.

If a bladder filling defect moves when the patient is repositioned, it is likely a bladder stone. Other possibilities include a blood clot, fungal ball, or a papillary urothelial tumor on a long stalk. Given that most patients will also present with associated pelvic pain, hematuria, voiding difficulties, or a history of urolithiasis, cystoscopy is often performed. This procedure will definitively identify any bladder calculi.

Treatment / Management

Medical Therapy

Dissolution of bladder stones, particularly uric acid stones, can sometimes be achieved with oral alkalinizing agents alone, provided the required higher pH level (usually between 6.5 and 7) can be maintained long enough. This technique is usually performed using oral potassium citrate, which can be supplemented with sodium bicarbonate if necessary. For most patients, this requires approximately 60 mEq of potassium citrate per day. Serum potassium levels and urinary pH levels should be monitored regularly during this therapy, and the dosage of potassium citrate should be titrated to maintain the optimal pH level.[49][50][51](B3)

Patients with a history of nephrolithiasis may benefit from a metabolic evaluation, which includes a 24-hour urine test to assess kidney stone risk factors and guide prophylactic therapy. Citric acid, glucono-delta-lactone, and magnesium carbonate can dissolve struvite (infection-related) stones but require the use of irrigating catheters. Due to the slow dissolution rate, this treatment is used infrequently.[52](A1)

Calcium phosphate is the primary component of the encrustations and debris that commonly clog urinary stents and catheters. Calcium phosphate forms only in an alkaline environment and can be dissolved with a mild acid. Periodic bladder instillations of a 0.25% acetic acid solution can help dissolve calcium phosphate crystals, reducing the risk of bladder stone formation. This approach also helps maintain the patency of Foley catheters and suprapubic tubes in patients whose urinary drainage tubes are prone to early clogging due to debris.

Surgical Therapy

Most bladder stones can be managed with endoscopic surgery. The underlying cause should also be addressed concurrently, when possible.[53] Most guidelines recommend treating bladder outlet obstruction when vesical calculi are present, with multiple studies supporting this approach.[27][54][55][56] However, as bladder stone formation is multifactorial, some recent reviews have questioned this recommendation, advocating for individualized decision-making instead.[57](B2)

Cystolitholapaxy can be performed cystoscopically for most types of bladder stones. Various disruptive or ablative therapies, including lasers, pneumatic-powered mechanical contact devices, ultrasound, and direct mechanical crushing with a lithotrite, can be used. Electrohydraulic devices are generally not used for bladder stones due to the tendency of the calculi to move, resulting in higher rates of mucosal bladder injury. Ultrasound and lithoclast devices typically fragment bladder stones more quickly than lasers, although all methods are considered effective. Laser treatment of bladder stones is increasingly becoming the standard due to its high stone-free success rate, low complication rate, and the ability to perform other endourological procedures, such as prostate resections and ureteroscopy.[58][59](A1)

Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (ESWL) can be equally effective for bladder stones, but the treatment head must be positioned above the patient (or the patient placed in a prone position) and may require multiple treatment sessions (up to 3) to achieve comparable results.[60][61][62][63][64][65][66] An advantage of ESWL is that it is the least invasive surgical option.[61][67] ESWL may also be used in children with bladder calculi.[60][68] Stones impacted in the urethra can be repositioned into the bladder and treated with ESWL.[65](A1)

Percutaneous suprapubic cystolitholapaxy is the preferred treatment for pediatric bladder stones, especially in males aged 16 or younger, to minimize urethral trauma.[69] Larger caliber instruments can be placed suprapubically rather than transurethrally, which is particularly advantageous in pediatric patients. A combined procedure using both suprapubic and cystoscopic approaches may be used in some cases. In adult male patients with outlet obstruction, transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) or a similar procedure is recommended, when indicated, immediately after the stone has been fragmented and removed.[70](B2)

In cases of extremely large bladder stones or prostates, open suprapubic surgery may be considered. This approach allows for the removal of the intact stone, followed by an open suprapubic prostatectomy, typically for prostates larger than 75 grams. The main advantages of open suprapubic cystostomy for bladder stone removal include reduced overall surgery time (approximately half the duration of endoscopic procedures), easy removal of large or multiple stones, the ability to remove stones difficult to fragment endoscopically, and the capability to handle stones adhered to the bladder lining. However, the disadvantages of this approach include longer hospital stays, additional postoperative pain, the need for an abdominal incision and drains, possible wound complications, and prolonged Foley catheterization time.

Bladder stones are rarely reported after renal transplantation, but when they occur, they are often associated with the use of nonabsorbable suture material.[70] Treatment of bladder stones in this population is similar to that for other patients with vesical calculi. Stone removal from the augmented bladder or urinary diversions may be performed using endoscopic, percutaneous, robotic, or open surgery, depending on the clinical situation.[71][72][73](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses of bladder stones include:

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia

- Clot

- Fungus ball

- Papillary urothelial carcinoma

- Passed renal or ureteral calculus

- Sloughed papilla

- Urinary tract infection

Prognosis

The prognosis for bladder stones is generally favorable when treated appropriately. Treatment depends on the underlying cause of the bladder stones.

Small bladder stones may pass easily, but larger stones can become lodged at the bladder neck or in the urethra, obstructing urine flow. If left untreated, bladder stones can lead to urinary tract damage, recurrent stone formation, bladder damage, urinary retention, or infection.

Complications

Bladder stones, particularly larger calculi, can lead to various complications, including:

- Frequent urination

- Hematuria

- Urinary obstruction

- Pain

- Possible association with bladder cancer

- Urethral obstruction

- Urinary retention

- Urinary tract infections

Deterrence and Patient Education

Once bladder stones have developed in a patient, the risk of recurrence increases. Identifying and addressing the underlying cause is crucial in preventing future stone formation.

Patients should be advised to maintain adequate hydration, as increased water intake helps prevent stone formation by diluting minerals that could otherwise precipitate in the urinary tract. If an enlarged prostate is causing obstruction, surgical intervention may be necessary to prevent urinary stasis and reduce the risk of recurrent stones.

Pearls and Other Issues

A metabolic evaluation, including 24-hour urine testing, a basic metabolic panel, and serum uric acid levels, is recommended for all patients with bladder calculi, particularly those with uric acid stones, nephrolithiasis, bladder stones without identifiable outlet obstruction or nidus, recurrent bladder stones, or a strong family history of urinary lithiasis.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Bladder stones are relatively uncommon in Western countries but continue to be a significant concern in many parts of the world. One of the primary causative factors is the failure to regularly empty the bladder. Catheters that are not changed for prolonged periods can predispose patients to bladder calculi. When Foley catheters are removed traumatically, it is crucial to inspect the catheter to ensure no balloon fragments or other pieces remain behind.

All members of the interprofessional healthcare care team must be aware of the risk of retained balloon fragments inside the bladder in such patients, as these fragments can eventually calcify. In such cases, cystoscopy, performed by a urologist and assisted by a nurse, is necessary to remove any retained fragments and prevent complications.

More frequent catheter changes and the judicious use of citric acid, glucono-delta-lactone with magnesium carbonate, and 0.25% acetic acid solutions can help minimize bladder stone formation, calcium phosphate deposits, and catheter encrustations. Pharmacists play a critical role in assessing drug treatments, identifying potential interactions, ensuring medication compliance, and reporting concerns to the interprofessional healthcare team. Specialty urologic nurses coordinate patient care, facilitate communication among team members, and provide comprehensive patient education. Close collaboration and coordination between urology, primary care, pharmacy, and nursing staff are essential to reducing the incidence of preventable bladder stones.[74]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Interior Anatomy of the Urinary Bladder. The interior of the bladder, including the vertex, internal urethral orifice, uvula vesicae, torus ureteric, and the orifice of the ureter.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Vertical Section of the Urinary Bladder Wall. Anatomical features of the urinary bladder wall, including the transitional epithelium, submucous coat, inner layer of longitudinal muscle fibers, circular muscle fibers, and outer layer of longitudinal muscle fibers.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Yoshida S, Takazawa R, Uchida Y, Kohno Y, Waseda Y, Tsujii T. The significance of intraoperative renal pelvic urine and stone cultures for patients at a high risk of post-ureteroscopy systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Urolithiasis. 2019 Dec:47(6):533-540. doi: 10.1007/s00240-019-01112-6. Epub 2019 Feb 13 [PubMed PMID: 30758524]

Whittington JR, Simmons PM, Eltahawy EA, Magann EF. Bladder Stone in Pregnancy: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. The American journal of case reports. 2018 Dec 30:19():1546-1549. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.912614. Epub 2018 Dec 30 [PubMed PMID: 30594944]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVilla L, Capogrosso P, Capitanio U, Martini A, Briganti A, Salonia A, Montorsi F. Silodosin: An Update on Efficacy, Safety and Clinical Indications in Urology. Advances in therapy. 2019 Jan:36(1):1-18. doi: 10.1007/s12325-018-0854-2. Epub 2018 Dec 6 [PubMed PMID: 30523608]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePozzi M, Locatelli F, Galbiati S, Beretta E, Carnovale C, Clementi E, Strazzer S. Relationships between enteral nutrition facts and urinary stones in a cohort of pediatric patients in rehabilitation from severe acquired brain injury. Clinical nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2019 Jun:38(3):1240-1245. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2018.05.005. Epub 2018 May 14 [PubMed PMID: 29803667]

Lu J, Gao W, Fei C, Liao W, Hou G, Lin Y, Rao W, Yang Q, Sui X. Associated factors for benign prostatic hyperplasia in patients with bladder calculi. Urologia. 2025 Feb 20:():3915603251318869. doi: 10.1177/03915603251318869. Epub 2025 Feb 20 [PubMed PMID: 39980325]

Schwartz BF, Stoller ML. The vesical calculus. The Urologic clinics of North America. 2000 May:27(2):333-46 [PubMed PMID: 10778475]

Armbruster CE, Mobley HLT, Pearson MM. Pathogenesis of Proteus mirabilis Infection. EcoSal Plus. 2018 Feb:8(1):. doi: 10.1128/ecosalplus.ESP-0009-2017. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29424333]

Manjunath AS, Hofer MD. Urologic Emergencies. The Medical clinics of North America. 2018 Mar:102(2):373-385. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2017.10.013. Epub 2017 Dec 20 [PubMed PMID: 29406065]

Foo KT. Pathophysiology of clinical benign prostatic hyperplasia. Asian journal of urology. 2017 Jul:4(3):152-157. doi: 10.1016/j.ajur.2017.06.003. Epub 2017 Jun 13 [PubMed PMID: 29264224]

Takasaki E, Suzuki T, Honda M, Imai T, Maeda S, Hosoya Y. Chemical compositions of 300 lower urinary tract calculi and associated disorders in the urinary tract. Urologia internationalis. 1995:54(2):89-94 [PubMed PMID: 7538235]

Douenias R, Rich M, Badlani G, Mazor D, Smith A. Predisposing factors in bladder calculi. Review of 100 cases. Urology. 1991 Mar:37(3):240-3 [PubMed PMID: 2000681]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJung JH, Park J, Kim WT, Kim HW, Kim HJ, Hong S, Yang HJ, Chung H. The association of benign prostatic hyperplasia with lower urinary tract stones in adult men: A retrospective multicenter study. Asian journal of urology. 2018 Apr:5(2):118-121. doi: 10.1016/j.ajur.2017.06.008. Epub 2017 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 29736374]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSmith JM, O'Flynn JD. Vesical stone: The clinical features of 652 cases. Irish medical journal. 1975 Feb 22:68(4):85-9 [PubMed PMID: 1112692]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYang X, Wang K, Zhao J, Yu W, Li L. The value of respective urodynamic parameters for evaluating the occurrence of complications linked to benign prostatic enlargement. International urology and nephrology. 2014 Sep:46(9):1761-8. doi: 10.1007/s11255-014-0722-1. Epub 2014 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 24811567]

Krambeck AE, Handa SE, Lingeman JE. Experience with more than 1,000 holmium laser prostate enucleations for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Journal of urology. 2010 Mar:183(3):1105-9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.11.034. Epub 2010 Jan 21 [PubMed PMID: 20092844]

Mebust WK, Holtgrewe HL, Cockett AT, Peters PC. Transurethral prostatectomy: immediate and postoperative complications. a cooperative study of 13 participating institutions evaluating 3,885 patients. 1989. The Journal of urology. 2002 Feb:167(2 Pt 2):999-1003; discussion 1004 [PubMed PMID: 11908420]

Kohler-Ockmore J, Feneley RC. Long-term catheterization of the bladder: prevalence and morbidity. British journal of urology. 1996 Mar:77(3):347-51 [PubMed PMID: 8814836]

Adegeest CY, van Gent JAN, Stolwijk-Swüste JM, Post MWM, Vandertop WP, Öner FC, Peul WC, Wengel PVT. Influence of severity and level of injury on the occurrence of complications during the subacute and chronic stage of traumatic spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Journal of neurosurgery. Spine. 2022 Apr 1:36(4):632-652. doi: 10.3171/2021.7.SPINE21537. Epub 2021 Nov 12 [PubMed PMID: 34767527]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLal B, Paryani JP, Memon SU. CHILDHOOD BLADDER STONES-AN ENDEMIC DISEASE OF DEVELOPING COUNTRIES. Journal of Ayub Medical College, Abbottabad : JAMC. 2015 Jan-Mar:27(1):17-21 [PubMed PMID: 26182729]

Halstead SB. Epidemiology of bladder stone of children: precipitating events. Urolithiasis. 2016 Apr:44(2):101-8. doi: 10.1007/s00240-015-0835-8. Epub 2015 Nov 11 [PubMed PMID: 26559057]

Soliman NA, Rizvi SAH. Endemic bladder calculi in children. Pediatric nephrology (Berlin, Germany). 2017 Sep:32(9):1489-1499. doi: 10.1007/s00467-016-3492-4. Epub 2016 Nov 15 [PubMed PMID: 27848095]

Aurora AL, Taneja OP, Gupta DN. Bladder stone disease of childhood. II. A clinico-pathological study. Acta paediatrica Scandinavica. 1970 Jul:59(4):385-98 [PubMed PMID: 5447682]

Valyasevi A, Halstead SB, Dhanamitta S. Studies of bladder stone disease in Thailand. VI. Urinary studies in children, 2-10 years old, resident in a hypo- and hyperendemic area. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 1967 Dec:20(12):1362-8 [PubMed PMID: 6074673]

DeVivo MJ, Fine PR, Cutter GR, Maetz HM. The risk of bladder calculi in patients with spinal cord injuries. Archives of internal medicine. 1985 Mar:145(3):428-30 [PubMed PMID: 3977510]

Bartel P, Krebs J, Wöllner J, Göcking K, Pannek J. Bladder stones in patients with spinal cord injury: a long-term study. Spinal cord. 2014 Apr:52(4):295-7. doi: 10.1038/sc.2014.1. Epub 2014 Jan 28 [PubMed PMID: 24469146]

Ord J, Lunn D, Reynard J. Bladder management and risk of bladder stone formation in spinal cord injured patients. The Journal of urology. 2003 Nov:170(5):1734-7 [PubMed PMID: 14532765]

Romero-Otero J, García-Gómez B, García-González L, García-Rojo E, Abad-López P, Justo-Quintas J, Duarte-Ojeda J, Rodríguez-Antolín A. Critical analysis of a multicentric experience with holmium laser enucleation of the prostate for benign prostatic hyperplasia: outcomes and complications of 10 years of routine clinical practice. BJU international. 2020 Jul:126(1):177-182. doi: 10.1111/bju.15028. Epub 2020 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 32020749]

Schlomer BJ, Copp HL. Cumulative incidence of outcomes and urologic procedures after augmentation cystoplasty. Journal of pediatric urology. 2014 Dec:10(6):1043-50. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2014.03.007. Epub 2014 Apr 13 [PubMed PMID: 24766857]

Hensle TW, Bingham J, Lam J, Shabsigh A. Preventing reservoir calculi after augmentation cystoplasty and continent urinary diversion: the influence of an irrigation protocol. BJU international. 2004 Mar:93(4):585-7 [PubMed PMID: 15008735]

Husmann DA. Long-term complications following bladder augmentations in patients with spina bifida: bladder calculi, perforation of the augmented bladder and upper tract deterioration. Translational andrology and urology. 2016 Feb:5(1):3-11. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-4683.2015.12.06. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26904407]

Knap MM, Lundbeck F, Overgaard J. Early and late treatment-related morbidity following radical cystectomy. Scandinavian journal of urology and nephrology. 2004:38(2):153-60 [PubMed PMID: 15204405]

Turk TM, Koleski FC, Albala DM. Incidence of urolithiasis in cystectomy patients after intestinal conduit or continent urinary diversion. World journal of urology. 1999 Oct:17(5):305-7 [PubMed PMID: 10552149]

Mosa MM, Alsayed-Ahmad ZA, Razzouk Q, Alhmaidy O, Ismaeel H, Al Ahmad Y. Extraction of a giant bladder stone (560 g) in a young female: A case report. International journal of surgery case reports. 2024 Jun:119():109653. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2024.109653. Epub 2024 Apr 20 [PubMed PMID: 38678989]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHuang W, Cao JJ, Cao M, Wu HS, Yang YY, Xu ZM, Jin XD. Risk factors for bladder calculi in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Medicine. 2017 Aug:96(32):e7728. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007728. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28796057]

Chow KS, Chou CY. A boy with a large bladder stone. Pediatrics and neonatology. 2008 Aug:49(4):150-3. doi: 10.1016/S1875-9572(08)60031-5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19054922]

Li WM, Chou YH, Li CC, Liu CC, Huang SP, Wu WJ, Huang CH. Local factors compared with systemic factors in the formation of bladder uric acid stones. Urologia internationalis. 2009:82(1):48-52. doi: 10.1159/000176025. Epub 2009 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 19172097]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWei B, Pan Y, Gan S. A systematic scoping review of Jackstone Calculi: clinical presentation and management. Urolithiasis. 2024 Nov 30:53(1):1. doi: 10.1007/s00240-024-01670-4. Epub 2024 Nov 30 [PubMed PMID: 39614889]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceYu Z, Yue W, Jiuzhi L, Youtao J, Guofei Z, Wenbin G. The risk of bladder cancer in patients with urinary calculi: a meta-analysis. Urolithiasis. 2018 Nov:46(6):573-579. doi: 10.1007/s00240-017-1033-7. Epub 2018 Jan 5 [PubMed PMID: 29305631]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLa Vecchia C, Negri E, D'Avanzo B, Savoldelli R, Franceschi S. Genital and urinary tract diseases and bladder cancer. Cancer research. 1991 Jan 15:51(2):629-31 [PubMed PMID: 1985779]

Chung SD, Tsai MC, Lin CC, Lin HC. A case-control study on the association between bladder cancer and prior bladder calculus. BMC cancer. 2013 Mar 15:13():117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-117. Epub 2013 Mar 15 [PubMed PMID: 23497224]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJhamb M, Lin J, Ballow R, Kamat AM, Grossman HB, Wu X. Urinary tract diseases and bladder cancer risk: a case-control study. Cancer causes & control : CCC. 2007 Oct:18(8):839-45 [PubMed PMID: 17593531]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWard JB, Feinstein L, Pierce C, Lim J, Abbott KC, Bavendam T, Kirkali Z, Matlaga BR, NIDDK Urologic Diseases in America Project. Pediatric Urinary Stone Disease in the United States: The Urologic Diseases in America Project. Urology. 2019 Jul:129():180-187. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2019.04.012. Epub 2019 Apr 18 [PubMed PMID: 31005657]

Mahdy A. Comments on Badejoko et al.: Overflow urinary incontinence due to bladder stones. International urogynecology journal. 2014 Oct:25(10):1445. doi: 10.1007/s00192-014-2472-0. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25047899]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMukherjee S, Sinha RK, Hamdoon M, Abbaraju J. Obstructive uropathy from a giant urinary bladder stone: a rare urological emergency. BMJ case reports. 2021 Jan 19:14(1):. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-234339. Epub 2021 Jan 19 [PubMed PMID: 33468632]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAdhikari R, Baral HP, Bhattarai U, Gautam RK, Kunwar KJ, Shrestha D, Katwal BM. A Rare Case Report of Giant Urinary Bladder Stone Causing Recurrent Dysuria in a Woman. Case reports in urology. 2022:2022():4835945. doi: 10.1155/2022/4835945. Epub 2022 Aug 27 [PubMed PMID: 36065329]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSharma M, Karn M, Adhikari H, Basnet B, Bhattarai I, Chapagain S, Pandit C. Vesicovaginal fistula associated with massive bladder calculi: An urogynecological case report. Clinical case reports. 2023 Dec:11(12):e8281. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.8281. Epub 2023 Dec 5 [PubMed PMID: 38076019]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFrancisca, Kholis K, Palinrungi MA, Syahrir S, Syarif, Faruk M. Bladder stones associated with vesicovaginal fistula: A case report. International journal of surgery case reports. 2020:75():122-125. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2020.09.028. Epub 2020 Sep 11 [PubMed PMID: 32950941]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLinsenmeyer MA, Linsenmeyer TA. Accuracy of bladder stone detection using abdominal x-ray after spinal cord injury. The journal of spinal cord medicine. 2004:27(5):438-42 [PubMed PMID: 15648797]

Hemminki K, Hemminki O, Försti A, Sundquist K, Sundquist J, Li X. Familial risks in urolithiasis in the population of Sweden. BJU international. 2018 Mar:121(3):479-485. doi: 10.1111/bju.14096. Epub 2018 Jan 14 [PubMed PMID: 29235239]

Brisbane W, Bailey MR, Sorensen MD. An overview of kidney stone imaging techniques. Nature reviews. Urology. 2016 Nov:13(11):654-662. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2016.154. Epub 2016 Aug 31 [PubMed PMID: 27578040]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOmar M, Chaparala H, Monga M, Sivalingam S. Contemporary Imaging Practice Patterns Following Ureteroscopy for Stone Disease. Journal of endourology. 2015 Oct:29(10):1122-5. doi: 10.1089/end.2015.0088. Epub 2015 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 25963170]

Gonzalez RD, Whiting BM, Canales BK. The history of kidney stone dissolution therapy: 50 years of optimism and frustration with renacidin. Journal of endourology. 2012 Feb:26(2):110-8. doi: 10.1089/end.2011.0380. Epub 2011 Oct 14 [PubMed PMID: 21999455]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceJia Q, Jin T, Wang K, Zheng Z, Deng J, Wang H. Comparison of 2 Kinds of Methods for the Treatment of Bladder Calculi. Urology. 2018 Apr:114():233-235. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2018.01.015. Epub 2018 Feb 2 [PubMed PMID: 29410329]

Guo RQ, Yu W, Meng YS, Zhang K, Xu B, Xiao YX, Wu SL, Pan BN. Correlation of benign prostatic obstruction-related complications with clinical outcomes in patients after transurethral resection of the prostate. The Kaohsiung journal of medical sciences. 2017 Mar:33(3):144-151. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2017.01.002. Epub 2017 Feb 13 [PubMed PMID: 28254117]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRomero-Otero J, García González L, García-Gómez B, Alonso-Isa M, García-Rojo E, Gil-Moradillo J, Duarte-Ojeda JM, Rodríguez-Antolín A. Analysis of Holmium Laser Enucleation of the Prostate in a High-Volume Center: The Impact of Concomitant Holmium Laser Cystolitholapaxy. Journal of endourology. 2019 Jul:33(7):564-569. doi: 10.1089/end.2019.0019. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30773913]

Tangpaitoon T, Marien T, Kadihasanoglu M, Miller NL. Does Cystolitholapaxy at the Time of Holmium Laser Enucleation of the Prostate Affect Outcomes? Urology. 2017 Jan:99():192-196. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2016.08.042. Epub 2016 Sep 13 [PubMed PMID: 27637344]

Maresca G, Mc Clinton S, Swami S, El-Mokadem I, Donaldson JF. Do men with bladder stones benefit from treatment of benign prostatic obstruction? BJU international. 2022 Nov:130(5):619-627. doi: 10.1111/bju.15761. Epub 2022 May 17 [PubMed PMID: 35482471]

Cerrato C, Frascheri MF, Fernandez SN, Emiliani E, Arena P, Pietropaolo A, Somani BK. Emerging Role of Laser Lithotripsy for Bladder Stones: Real-World Outcomes from Two European Endourology Centers with a Systematic Review of Literature. Journal of endourology. 2025 Mar:39(3):285-291. doi: 10.1089/end.2024.0640. Epub 2025 Feb 5 [PubMed PMID: 39909483]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAkram M, Cerrato C, Enikeev D, Tokas T, Somani BK. Safety and efficacy of laser lithotripsy for treatment of bladder calculi: evidence from a systematic literature review. Current opinion in urology. 2024 Nov 14:():. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0000000000001250. Epub 2024 Nov 14 [PubMed PMID: 39774916]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDonaldson JF, Ruhayel Y, Skolarikos A, MacLennan S, Yuan Y, Shepherd R, Thomas K, Seitz C, Petrik A, Türk C, Neisius A. Treatment of Bladder Stones in Adults and Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis on Behalf of the European Association of Urology Urolithiasis Guideline Panel. European urology. 2019 Sep:76(3):352-367. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2019.06.018. Epub 2019 Jul 13 [PubMed PMID: 31311676]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAli M, Hashem A, Helmy TE, Zewin T, Sheir KZ, Shokeir AA. Shock wave lithotripsy versus endoscopic cystolitholapaxy in the management of patients presenting with calcular acute urinary retention: a randomised controlled trial. World journal of urology. 2019 May:37(5):879-884. doi: 10.1007/s00345-018-2434-0. Epub 2018 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 30105456]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDavis NF, Donaldson JF, Shepherd R, Neisius A, Petrik A, Seitz C, Thomas K, Lombardo R, Tzelves L, Somani B, Gambarro G, Ruhayel Y, Türk C, Skolarikos A. Treatment outcomes of bladder stones in children with intact bladders in developing countries: A systematic review of }1000 cases on behalf of the European Association of Urology Bladder Stones Guideline panel. Journal of pediatric urology. 2022 Apr:18(2):132-140. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2022.01.007. Epub 2022 Jan 23 [PubMed PMID: 35148953]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTelha KA, Alkohlany K, Alnono I. Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy monotherapy for treating patients with bladder stones. Arab journal of urology. 2016 Sep:14(3):207-10. doi: 10.1016/j.aju.2016.06.001. Epub 2016 Jul 25 [PubMed PMID: 27547462]

Al-Ansari A, Shamsodini A, Younis N, Jaleel OA, Al-Rubaiai A, Shokeir AA. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy monotherapy for treatment of patients with urethral and bladder stones presenting with acute urinary retention. Urology. 2005 Dec:66(6):1169-71 [PubMed PMID: 16360434]

el-Sherif AE, Prasad K. Treatment of urethral stones by retrograde manipulation and extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. British journal of urology. 1995 Dec:76(6):761-4 [PubMed PMID: 8535722]

García Cardoso JV, González Enguita C, Cabrera Pérez J, Rodriguez Miñón JL, Calahorra Fernández FJ, Vela Navarrete R. [Bladder calculi. Is extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy the first choice treatment?]. Archivos espanoles de urologia. 2003 Dec:56(10):1111-6 [PubMed PMID: 14763416]

Bhatia V, Biyani CS. A comparative study of cystolithotripsy and extracorporeal shock wave therapy for bladder stones. International urology and nephrology. 1994:26(1):26-31 [PubMed PMID: 8026920]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRizvi SA, Naqvi SA, Hussain Z, Hashmi A, Hussain M, Zafar MN, Sultan S, Mehdi H. Management of pediatric urolithiasis in Pakistan: experience with 1,440 children. The Journal of urology. 2003 Feb:169(2):634-7 [PubMed PMID: 12544331]

Xie Y, Zhang M, Liu K. Comparison of the Efficacy of Transurethral Cystolithotripsy and Percutaneous Cystolithotomy in the Treatment of Male Children with 20-30 mm Bladder Stones: A Retrospective Study. Archivos espanoles de urologia. 2025 Jan:78(1):71-76. doi: 10.56434/j.arch.esp.urol.20257801.9. Epub [PubMed PMID: 39943636]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSavin Z, Dayan Rahmani L, Frangopoulos E, Gupta K, Durbhakula V, Gallante B, Atallah WM, Gupta M. Is Treating Bladder Outlet Really Needed when Removing Bladder Stones: Outcomes of Bladder Stones Removal Without Concomitant BPO Surgery. Journal of endourology. 2025 Jan:39(1):65-70. doi: 10.1089/end.2024.0682. Epub 2024 Nov 26 [PubMed PMID: 39587910]

Surer I, Ferrer FA, Baker LA, Gearhart JP. Continent urinary diversion and the exstrophy-epispadias complex. The Journal of urology. 2003 Mar:169(3):1102-5 [PubMed PMID: 12576862]

Inzillo R, Kwe JE, Simonetti E, Milandri R, Grande M, Campobasso D, Ferretti S, Rocco B, Micali S, Frattini A. Percutaneous and endoscopic combined treatment of bladder and renal lithiasis in mitrofanoff conduit. International braz j urol : official journal of the Brazilian Society of Urology. 2022 May-Jun:48(3):598-599. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2021.0815. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35263058]

Haffar A, Crigger C, Trump T, Jessop M, Salkini MW. Minimally Invasive Robotic-Assisted Cystolithotomy in a Complicated Urinary Diversion: A Feasible and Safe Approach. Case reports in urology. 2021:2021():8345092. doi: 10.1155/2021/8345092. Epub 2021 Dec 14 [PubMed PMID: 34950523]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAbergel S, Peyronnet B, Seguin P, Bensalah K, Traxer O, Freund Y. Management of urinary stone disease in general practice: A French Delphi study. The European journal of general practice. 2016 Jun:22(2):103-10. doi: 10.3109/13814788.2016.1149568. Epub 2016 Apr 19 [PubMed PMID: 27092401]