C-Reactive Protein: Clinical Relevance and Interpretation

C-Reactive Protein: Clinical Relevance and Interpretation

Introduction

C-reactive protein (CRP), first identified by Tillett and Francis in 1930, derives its name from its reaction with the C carbohydrate antigen in the capsule of Streptococcus pneumoniae during acute inflammation. CRP is a pentameric protein synthesized by the liver in response to inflammation, with a molecular weight of approximately 115 kDa. This substance exhibits a characteristic "jelly-like lectin fold."[1]

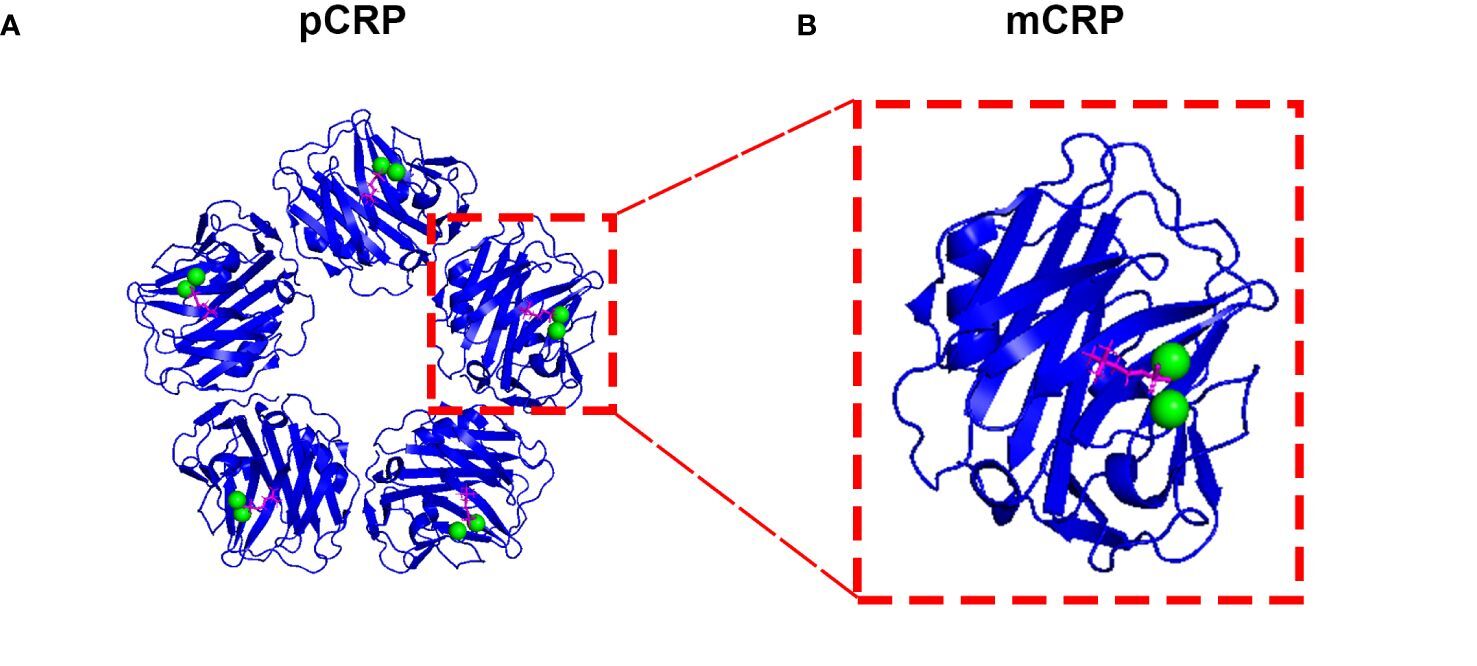

CRP typically consists of 5 identical subunits arranged into a cyclic pentamer around a central pore. However, the protein exists in 2 primary isoforms: the pentameric form (pCRP) and the monomeric form (mCRP). PCRP is the circulating form under normal conditions and is primarily anti-inflammatory. Meanwhile, mCRP arises during inflammation and has pro-inflammatory effects.

The transition between these 2 forms occurs when pCRP dissociates into monomers, typically in response to tissue damage or other inflammatory stimuli. This structural shift is significant as mCRP exhibits pro-inflammatory properties, such as platelet activation, leukocyte recruitment, and endothelial dysfunction, which contribute to the pathogenesis of various diseases, including cardiovascular conditions.[2][3] These structural and functional differences underscore CRP's dual role in inflammation, both as a mediator of anti-inflammatory responses and a promoter of inflammatory processes during pathological conditions.

CRP functions as an acute-phase reactant, primarily induced by interleukin 6 acting on the hepatic gene responsible for CRP transcription during inflammatory or infectious processes. Studies have explored the potential link between CRP dysregulation in the clearance of apoptotic cells and cellular debris and the onset of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), though definitive evidence is currently lacking. Animal models of alveolitis have demonstrated protective effects of CRP in lung tissue, where it reduces neutrophil-mediated alveolar damage and protein leakage into the lungs.

This protein plays a role in recognizing and facilitating the clearance of foreign pathogens and damaged cells by binding to phosphocholine, phospholipids, histones, chromatin, and fibronectin (see Image. C-Reactive Protein Isoforms and Their Phosphocholine Complexes). CRP activates the classical complement pathway and engages phagocytic cells via Fc receptors, expediting the removal of apoptotic cells, necrotic debris, and pathogens.

Pathologic activation can occur in autoimmune processes when CRP binds to autoantibodies that expose phosphocholine residues. This mechanism contributes to disease in conditions such as idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. In certain contexts, CRP-mediated complement activation may exacerbate tissue damage through downstream inflammatory cytokine release.[4][5][6]

Unlike the erythrocyte sedimentation rate, which indirectly reflects inflammation, CRP levels change rapidly in response to inflammatory stimuli. CRP concentrations increase acutely and decline promptly once the underlying trigger resolves. Chronic elevation may indicate ongoing inflammation from persistent infections or inflammatory arthritides, such as rheumatoid arthritis.

Numerous conditions can elevate CRP levels, including both acute and chronic processes, whether infectious or noninfectious. Markedly elevated CRP concentrations most commonly reflect infection, representing an example of pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) recognition.[7] Trauma can also induce a significant elevation of CRP through the alarmin response.

More modest CRP increases often arise from a broader spectrum of stimuli, including sleep disturbances, periodontal disease, or low-grade systemic inflammation. Higher CRP levels correlate with reduced engagement in light physical activity or moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, as well as increased sedentary time.[8]

Specimen Collection

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Specimen Collection

A peripheral venous blood sample is typically obtained by a phlebotomist. The procedure involves placing a snug tourniquet around the upper arm while the patient pumps their fist several times to promote venous distention. The phlebotomist palpates for a suitable vein, cleanses the site with an alcohol pad, and allows the area to air-dry before introducing the needle. Once the blood is collected into a vial, the tourniquet is released, and the needle is withdrawn. Manual pressure is applied to the venipuncture site until hemostasis is achieved, usually within 1 minute, followed by placement of a bandage.

Medication history should be reviewed, as certain drugs may affect CRP levels (see Interfering Factors). Fasting is not required before testing. No special preparations are necessary. Minor complications may include localized oozing, bruising, or tenderness. Infection at the venipuncture site is rare. Although other body fluids, such as synovial fluid, may contain CRP, testing these fluids is not a routine practice.

CRP quantification is performed using immunoassays or laser nephelometry—methods that are inexpensive, accurate, and rapid. For detecting lower concentrations of CRP (0.3-1.0 mg/L), high-sensitivity CRP (hsCRP) assays are preferred due to greater precision at low levels. The term "high-sensitivity" refers solely to the analytical technique, not to a distinct clinical interpretation or differential diagnosis.

Recent advances have introduced reliable point-of-care CRP testing options cleared by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The ProciseDx CRP Assay, approved in 2022, delivers quantitative CRP results from serum samples in under 5 minutes using a compact fluorescence-based device. (Source: ProciseDx, 2022) The Siemens Revised CRP (RCRP) Flex Reagent Cartridge Assay, cleared in early 2023, offers a high-sensitivity format with an analytical range of 5.0 to 250.0 mg/L, suitable for cardiovascular risk stratification. (Source: FDA, 2023) These platforms enhance clinical efficiency by providing rapid, reliable measurements at or near the bedside. Innovative approaches, such as integrating paper-based microfluidic immunoassays with smartphones (eg, the CRP-Chip), offer low-cost, rapid testing options suitable for resource-limited environments.[9]

Indications

This test is performed when a physician suspects acute or chronic inflammation, such as in conditions like SLE or rheumatoid arthritis, or when an infection is being considered. The utility of hsCRP for cardiac screening remains debatable. Although some correlation exists between elevated hsCRP levels and cardiovascular risk, the test's poor specificity complicates its clinical application. Further evaluation of its role in cardiovascular risk assessment is ongoing.[10][11][12]

The FDA has approved several types of CRP assays for clinical use. Conventional CRP assays are typically used to evaluate infection, inflammatory disorders, and tissue injury. HsCRP assays are designed to assess inflammation in individuals who are otherwise healthy. Cardiac CRP (cCRP) assays are indicated for identifying and stratifying individuals at risk of developing cardiovascular disease in the future. (Source: FDA, 2005)

Potential Diagnosis

CRP elevation in patients with a history of venous thromboembolism (VTE), cancer, COVID-19, or obesity may aid in predicting VTE risk.[13] Log-transformed hsCRP-to-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (Ln HCHR) and log-transformed hsCRP-to-lymphocyte count ratio (Ln HCLR) show a positive association with the prevalence of heart failure in the U.S. population.[14]

Higher CRP levels serve as independent risk factors for cardiac mortality and are directly proportional to the risk of cardiovascular disease. Elevated CRP plasma levels also correlate with cancer risk, with higher levels observed in gastric, colorectal, and lung cancer. Elevated CRP may serve as a potential biomarker for stratifying cancer risk.[15]

In patients diagnosed with cardiovascular disease, increased CRP levels independently associate with a heightened risk of both heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).[16]

Frailty, characterized by multisystem dysregulation, decreased resilience, reduced physiologic reserve, and increased susceptibility to stressors, is emerging as closely linked to low-grade chronic inflammation. Higher levels of hsCRP correlate with an increased risk of frailty progression.[17]

Normal and Critical Findings

Laboratory values for CRP vary, with no standardized reporting method currently in use. Results are typically presented in either mg/dL or mg/L, with hsCRP commonly reported in mg/dL.

The standard interpretation of CRP levels is as follows:

- Less than 0.3 mg/dL: Normal, typically observed in most healthy adults

- 0.3 to 1.0 mg/dL: Normal or minor elevation, often seen in conditions such as obesity, pregnancy, depression, diabetes, common cold, gingivitis, periodontitis, sedentary lifestyle, cigarette smoking, and genetic polymorphisms

- 1.0 to 10.0 mg/dL: Moderate elevation, commonly associated with systemic inflammation such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, other autoimmune diseases, malignancies, myocardial infarction, pancreatitis, and bronchitis

- More than 10.0 mg/dL: Marked elevation, typically linked to acute bacterial infections, viral infections, systemic vasculitis, and major trauma

- More than 50.0 mg/dL: Severe elevation, generally seen in acute bacterial infections

When used for cardiac risk stratification, hsCRP levels are interpreted as follows:

- Below 1 mg/L: Low cardiovascular risk

- Between 1 and 3 mg/L: Moderate cardiovascular risk

- Above 3 mg/L: High cardiovascular risk [18][19]

The interpretation of CRP levels is essential for assessing the degree of inflammation and associated risks in patients. Clinicians can use these values to monitor disease progression, guide treatment strategies, and identify potential complications.

Interfering Factors

Certain pharmacological agents, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and statins, can reduce CRP levels. Recent injury or illness may elevate levels, particularly when using the test for cardiac risk stratification. Magnesium supplementation can diminish CRP levels.

Emerging pharmacological agents, including biologics like the interleukin 6 receptor antagonist tocilizumab, have demonstrated efficacy in lowering CRP levels in conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis.[20] Additionally, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists, commonly used in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus, have been associated with reductions in CRP levels, reflecting their anti-inflammatory properties.[21] Sustained reductions in CRP levels have also been associated with lifestyle modifications, including increased physical activity, improved sleep quality, stress reduction strategies, and adherence to anti-inflammatory dietary patterns.[22]

Genetic polymorphisms within the CRP gene, particularly single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the promoter region, can influence baseline CRP levels. These genetic variations may account for individual differences in CRP concentrations and should be considered when interpreting results.[23]

Mild CRP elevations may occur in the absence of overt systemic inflammation. Levels tend to be higher in women and older adults. Chronic conditions, such as obesity, smoking, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and insomnia, are associated with low-grade inflammation and can elevate CRP, requiring cautious interpretation in these contexts.

Mental health disorders, particularly depression and anxiety, have been explored in relation to CRP levels. However, after adjusting for confounding variables, including medical, social, and demographic factors such as sex, age, and race, these associations tend to weaken, suggesting indirect rather than causal relationships.[24]

Complications

Given the highly variable causes of CRP elevation, marginal increases can be difficult to interpret and should not be used as an isolated test result without considering the clinical context. Extremely high levels are helpful in distinguishing between infection and inflammation, but levels between 1 mg/dL and 10 mg/dL present challenges in interpretation. Chronic conditions, such as inflammatory arthritis or SLE, can cause persistently elevated CRP levels, complicating the use of hsCRP as a predictive marker for cardiovascular disease.

CRP acts as a nonspecific indicator of inflammation, and its levels are influenced by factors such as age, sex, and comorbidities. Therefore, CRP results should be interpreted within the broader clinical context and, when necessary, complemented with other diagnostic tests to enhance accuracy.

Patient Safety and Education

Patients should be informed about the significance of CRP testing, particularly its role in detecting inflammation and how the results contribute to their care plan. Clear communication helps set expectations and enhance understanding of the test’s purpose. Patients should also be educated on factors that may influence CRP levels, such as medications, lifestyle habits, and chronic conditions like obesity or smoking. Providing adequate information about this test ensures accurate analysis of results and helps avoid misinterpretation caused by external factors. Educating patients fosters informed decision-making, improving their engagement in the diagnostic process and overall care.

Clinical Significance

CRP levels greater than 50 mg/dL are linked to bacterial infections in approximately 90% of cases. Multiple studies have explored CRP as a prognostic marker in both acute and chronic infections, including hepatitis C, dengue, and malaria.[25][26][27] Mild elevations, however, may lack clinical relevance. Careful clinical correlation remains essential when interpreting CRP results.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

C-Reactive Protein Isoforms and Their Phosphocholine Complexes. This image shows the ribbon diagrams of the pentameric (A: pCRP) and monomeric (B: mCRP) isoforms of C-reactive protein. Each of the binding sites contains 1 phosphocholine moiety (magenta) and 2 calcium ions (green).

Zhou HH, Tang YL, Xu TH, Cheng B. C-reactive protein: structure, function, regulation, and role in clinical diseases. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1425168. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1425168.

References

Zhou HH, Tang YL, Xu TH, Cheng B. C-reactive protein: structure, function, regulation, and role in clinical diseases. Frontiers in immunology. 2024:15():1425168. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1425168. Epub 2024 Jun 14 [PubMed PMID: 38947332]

Melnikov I, Kozlov S, Saburova O, Avtaeva Y, Guria K, Gabbasov Z. Monomeric C-Reactive Protein in Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: Advances and Perspectives. International journal of molecular sciences. 2023 Jan 20:24(3):. doi: 10.3390/ijms24032079. Epub 2023 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 36768404]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRajab IM, Hart PC, Potempa LA. How C-Reactive Protein Structural Isoforms With Distinctive Bioactivities Affect Disease Progression. Frontiers in immunology. 2020:11():2126. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.02126. Epub 2020 Sep 10 [PubMed PMID: 33013897]

Cleland DA, Eranki AP. Procalcitonin. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969616]

Jungen MJ, Ter Meulen BC, van Osch T, Weinstein HC, Ostelo RWJG. Inflammatory biomarkers in patients with sciatica: a systematic review. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2019 Apr 9:20(1):156. doi: 10.1186/s12891-019-2541-0. Epub 2019 Apr 9 [PubMed PMID: 30967132]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKramer NE, Cosgrove VE, Dunlap K, Subramaniapillai M, McIntyre RS, Suppes T. A clinical model for identifying an inflammatory phenotype in mood disorders. Journal of psychiatric research. 2019 Jun:113():148-158. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.02.005. Epub 2019 Feb 10 [PubMed PMID: 30954775]

Vanderschueren S, Deeren D, Knockaert DC, Bobbaers H, Bossuyt X, Peetermans W. Extremely elevated C-reactive protein. European journal of internal medicine. 2006 Oct:17(6):430-3 [PubMed PMID: 16962952]

You Y. Accelerometer-measured physical activity and sedentary behaviour are associated with C-reactive protein in US adults who get insufficient sleep: A threshold and isotemporal substitution effect analysis. Journal of sports sciences. 2024 Mar:42(6):527-536. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2024.2348906. Epub 2024 May 2 [PubMed PMID: 38695324]

Dong M, Wu J, Ma Z, Peretz-Soroka H, Zhang M, Komenda P, Tangri N, Liu Y, Rigatto C, Lin F. Rapid and Low-Cost CRP Measurement by Integrating a Paper-Based Microfluidic Immunoassay with Smartphone (CRP-Chip). Sensors (Basel, Switzerland). 2017 Mar 26:17(4):. doi: 10.3390/s17040684. Epub 2017 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 28346363]

Eschborn S, Weitkamp JH. Procalcitonin versus C-reactive protein: review of kinetics and performance for diagnosis of neonatal sepsis. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association. 2019 Jul:39(7):893-903. doi: 10.1038/s41372-019-0363-4. Epub 2019 Mar 29 [PubMed PMID: 30926891]

Darooghegi Mofrad M, Milajerdi A, Koohdani F, Surkan PJ, Azadbakht L. Garlic Supplementation Reduces Circulating C-reactive Protein, Tumor Necrosis Factor, and Interleukin-6 in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. The Journal of nutrition. 2019 Apr 1:149(4):605-618. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxy310. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30949665]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDick AG, Magill N, White TCH, Kokkinakis M, Norman-Taylor F. C-reactive protein: what to expect after bony hip surgery for nonambulatory children and adolescents with cerebral palsy. Journal of pediatric orthopedics. Part B. 2019 Jul:28(4):309-313. doi: 10.1097/BPB.0000000000000634. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30925527]

Dix C, Zeller J, Stevens H, Eisenhardt SU, Shing KSCT, Nero TL, Morton CJ, Parker MW, Peter K, McFadyen JD. C-reactive protein, immunothrombosis and venous thromboembolism. Frontiers in immunology. 2022:13():1002652. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1002652. Epub 2022 Sep 13 [PubMed PMID: 36177015]

Zhang P, Mo D, Lin F, Dai H. Relationship between novel inflammatory markers derived from high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and heart failure: a cross-sectional study. BMC cardiovascular disorders. 2025 Feb 18:25(1):111. doi: 10.1186/s12872-025-04558-2. Epub 2025 Feb 18 [PubMed PMID: 39966719]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceZhu M, Ma Z, Zhang X, Hang D, Yin R, Feng J, Xu L, Shen H. C-reactive protein and cancer risk: a pan-cancer study of prospective cohort and Mendelian randomization analysis. BMC medicine. 2022 Sep 19:20(1):301. doi: 10.1186/s12916-022-02506-x. Epub 2022 Sep 19 [PubMed PMID: 36117174]

Burger PM, Koudstaal S, Mosterd A, Fiolet ATL, Teraa M, van der Meer MG, Cramer MJ, Visseren FLJ, Ridker PM, Dorresteijn JAN, UCC-SMART study group. C-Reactive Protein and Risk of Incident Heart Failure in Patients With Cardiovascular Disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2023 Aug 1:82(5):414-426. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2023.05.035. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37495278]

Luo YF, Cheng ZJ, Wang YF, Jiang XY, Lei SF, Deng FY, Ren WY, Wu LF. Unraveling the relationship between high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and frailty: evidence from longitudinal cohort study and genetic analysis. BMC geriatrics. 2024 Mar 4:24(1):222. doi: 10.1186/s12877-024-04836-2. Epub 2024 Mar 4 [PubMed PMID: 38439017]

Lee Y, McKechnie T, Doumouras AG, Handler C, Eskicioglu C, Gmora S, Anvari M, Hong D. Diagnostic Value of C-Reactive Protein Levels in Postoperative Infectious Complications After Bariatric Surgery: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obesity surgery. 2019 Jul:29(7):2022-2029. doi: 10.1007/s11695-019-03832-5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30895509]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceJohns I, Moschonas KE, Medina J, Ossei-Gerning N, Kassianos G, Halcox JP. Risk classification in primary prevention of CVD according to QRISK2 and JBS3 'heart age', and prevalence of elevated high-sensitivity C reactive protein in the UK cohort of the EURIKA study. Open heart. 2018:5(2):e000849. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2018-000849. Epub 2018 Nov 17 [PubMed PMID: 30564373]

Berman M, Ben-Ami R, Berliner S, Anouk M, Kaufman I, Broyde A, Borok S, Elkayam O. The Effect of Tocilizumab on Inflammatory Markers in Patients Hospitalized with Serious Infections. Case Series and Review of Literature. Life (Basel, Switzerland). 2021 Mar 20:11(3):. doi: 10.3390/life11030258. Epub 2021 Mar 20 [PubMed PMID: 33804790]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAmezcua-Castillo E, González-Pacheco H, Sáenz-San Martín A, Méndez-Ocampo P, Gutierrez-Moctezuma I, Massó F, Sierra-Lara D, Springall R, Rodríguez E, Arias-Mendoza A, Amezcua-Guerra LM. C-Reactive Protein: The Quintessential Marker of Systemic Inflammation in Coronary Artery Disease-Advancing toward Precision Medicine. Biomedicines. 2023 Sep 2:11(9):. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines11092444. Epub 2023 Sep 2 [PubMed PMID: 37760885]

Guo L, Huang Y, He J, Li D, Li W, Xiao H, Xu X, Zhang Y, Wang R. Associations of lifestyle characteristics with circulating immune markers in the general population based on NHANES 1999 to 2014. Scientific reports. 2024 Jun 11:14(1):13444. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-63875-2. Epub 2024 Jun 11 [PubMed PMID: 38862546]

Lopez-Roblero A, Serrano-Guzmán E, Guerrero-Báez RS, Delgado-Enciso I, Gómez-Manzo S, Aguilar-Fuentes J, Ovando-Garay V, Hernández-Ochoa B, Quezada-Cruz IC, Lopez-Lopez N, Canseco-Ávila LM. Single‑nucleotide polymorphisms in the promoter of the gene encoding for C‑reactive protein associated with acute coronary syndrome. Biomedical reports. 2024 Nov:21(5):150. doi: 10.3892/br.2024.1838. Epub 2024 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 39247423]

Figueroa-Hall LK, Xu B, Kuplicki R, Ford BN, Burrows K, Teague TK, Sen S, Yeh HW, Irwin MR, Savitz J, Paulus MP. Psychiatric symptoms are not associated with circulating CRP concentrations after controlling for medical, social, and demographic factors. Translational psychiatry. 2022 Jul 12:12(1):279. doi: 10.1038/s41398-022-02049-y. Epub 2022 Jul 12 [PubMed PMID: 35821205]

Bhardwaj N, Ahmed MZ, Sharma S, Nayak A, Anvikar AR, Pande V. C-reactive protein as a prognostic marker of Plasmodiumfalciparum malaria severity. Journal of vector borne diseases. 2019 Apr-Jun:56(2):122-126. doi: 10.4103/0972-9062.263727. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31397387]

Vuong NL, Le Duyen HT, Lam PK, Tam DTH, Vinh Chau NV, Van Kinh N, Chanpheaktra N, Lum LCS, Pleités E, Jones NK, Simmons CP, Rosenberger K, Jaenisch T, Halleux C, Olliaro PL, Wills B, Yacoub S. C-reactive protein as a potential biomarker for disease progression in dengue: a multi-country observational study. BMC medicine. 2020 Feb 17:18(1):35. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-1496-1. Epub 2020 Feb 17 [PubMed PMID: 32063229]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencede Souza Pires-Neto O, da Silva Graça Amoras E, Queiroz MAF, Demachki S, da Silva Conde SR, Ishak R, Cayres-Vallinoto IMV, Vallinoto ACR. Hepatic TLR4, MBL and CRP gene expression levels are associated with chronic hepatitis C. Infection, genetics and evolution : journal of molecular epidemiology and evolutionary genetics in infectious diseases. 2020 Jun:80():104200. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104200. Epub 2020 Jan 18 [PubMed PMID: 31962161]