Introduction

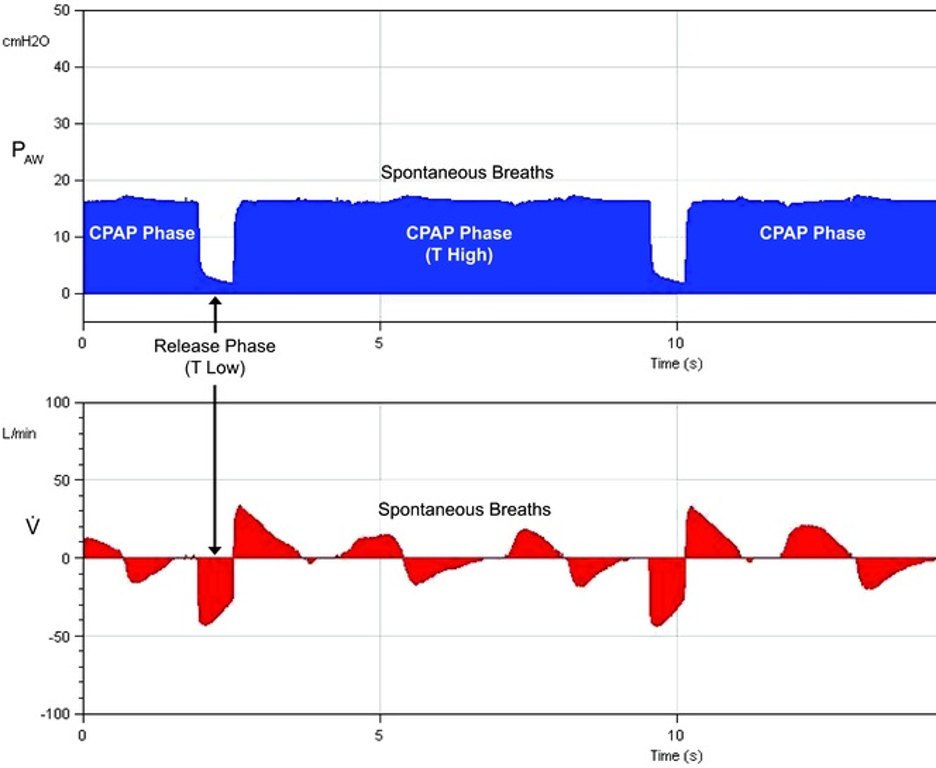

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) delivers a continuous flow of air to open the airways in individuals who are spontaneously breathing. Positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) refers to the pressure in the alveoli above atmospheric pressure at the end of expiration (see Image. Airway Pressure Release Ventilation Pressure Cycles with Superimposed Spontaneous Breathing).[1] CPAP maintains PEEP by delivering constant pressure during both inspiration and expiration, measured in cm H2O. Unlike bilevel positive airway pressure, which varies pressure during inhalation (inspiratory positive airway pressure) and exhalation (expiratory positive airway pressure), CPAP requires patients to initiate all breaths without additional pressure above the set level.

By maintaining PEEP, CPAP reduces atelectasis, increases alveolar surface area, improves ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) matching, enhances oxygenation, and maintains upper airway patency. While CPAP aids oxygenation, it is often inadequate for full ventilation support, which requires additional inspiratory pressure, as provided by noninvasive ventilation.[2] This activity reviews the mechanism of action, clinical indications, contraindications, preparation considerations, and potential complications of CPAP therapy in pediatric and adult populations.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Air travels from the nasal passages to the alveoli, moving through both the upper and lower airways, which serve as physical conduits with varying calibers and wall structures. CPAP modifies airway physiology at both extrathoracic and intrathoracic levels. Depending on the underlying condition, CPAP can play a key role in alleviating airway obstruction and improving respiratory mechanics.

Air flows sequentially through the nasopharynx, oropharynx, larynx, trachea, bronchi, and bronchioles before reaching the alveoli. Airway flow dynamics and mechanics vary depending on structural and functional factors. Obstruction can reduce maximal downstream flow, whether due to excess tissue, external compression, tonsillar hypertrophy, weakened musculature, fatty deposits, or secretions. This phenomenon follows the Sterling resistor principle, which states that maximal flow is directly proportional to the pressure differential between upstream and downstream segments of the collapsible airway and inversely proportional to resistance, which varies with the fourth power of airway diameter.[3][4]

CPAP maintains airway patency by increasing upstream pressure (ie, nasal pressure), thereby preventing collapse during both inspiration and expiration.[5] This modality also improves oxygenation by preserving alveolar patency and preventing end-expiratory collapse. In addition to respiratory effects, CPAP alters cardiopulmonary mechanics by influencing intrathoracic pressure and its interaction with ventricular pressures. These changes can affect preload and afterload.[6]

Indications

CPAP can be a preferred therapeutic option for various conditions that impair respiration, across outpatient and inpatient settings, and in acute or chronic presentations. CPAP supports patients with acute hypoxic respiratory failure, such as in acute pulmonary edema secondary to congestive heart failure, by improving cardiac output and enhancing V/Q matching. CPAP also aids oxygenation through the provision of PEEP, both before endotracheal intubation and during extubation in patients who continue to require positive pressure support without the need for invasive ventilation.[7][8] These benefits are particularly relevant in conditions such as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), especially in patients with obesity or congestive heart failure.

In neonatal intensive care, CPAP is used to treat preterm infants with underdeveloped lungs and respiratory distress syndrome due to surfactant deficiency.[9][10] This therapy also helps manage hypoxia and reduce the work of breathing in infants with conditions such as bronchiolitis, pneumonia, or tracheomalacia, where the airways are collapsible. Because CPAP helps maintain airway patency, the most common indication is OSA and, in select cases, central sleep apnea, particularly after treatment and optimization of underlying conditions such as heart failure.[11][12][13]

Contraindications

CPAP is unsuitable for individuals who are not spontaneously breathing. Patients with poor respiratory drive typically require invasive mechanical ventilation or noninvasive therapy with CPAP combined with pressure support and a backup rate, commonly delivered through bilevel positive airway pressure.

Relative contraindications for CPAP include the following:

- Lack of cooperation

- Anxiety

- Reduced consciousness or inability to protect the airway

- Unstable cardiorespiratory status or respiratory arrest

- Facial trauma or burns

- Recent facial, esophageal, or gastric surgery

- Air leak syndrome (eg, pneumothorax with bronchopleural fistula)

- Copious respiratory secretions

- Severe nausea and vomiting

- Severe air trapping diseases with hypercarbia (eg, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease)

CPAP is an effective therapy for managing various respiratory conditions, but proper patient selection is crucial to avoid complications. Careful consideration of contraindications ensures this therapy's safe and appropriate use in clinical practice.

Equipment

CPAP therapy utilizes machines designed to deliver a continuous flow of constant pressure.[14] Some CPAP machines include additional features, such as heated humidifiers, to enhance patient comfort. A key component of a CPAP machine is the interface for delivering pressure, which can vary based on the mask used.

CPAP may be administered through several interfaces. Nasal CPAP uses nasal prongs that fit directly into the nostrils or a small mask that covers the nose. Nasopharyngeal CPAP is delivered through a nasopharyngeal tube, an airway inserted through the nose with its tip terminating in the nasopharynx. This method bypasses the nasal cavity and delivers CPAP more distally. CPAP via a face mask involves a full mask covering the nose and mouth, ensuring a secure seal. This interface is particularly useful for patients who breathe through their mouths or require preoxygenation before intubation while breathing spontaneously. A CPAP machine also includes straps to secure the mask, a hose or tube connecting the mask to the machine’s motor, a motor that blows air into the tube, and an air filter to purify the air entering the nose.

Bubble CPAP is a mode of delivering CPAP used in neonates and infants, where pressure in the circuit is maintained by immersing the distal end of the expiratory tubing in water.[15] The depth of the tubing in the water determines the generated pressure. Blended and humidified oxygen is delivered via nasal prongs or nasal masks. As the gas flows through the system, it "bubbles" through the expiratory tubing into the water, producing a characteristic sound. Pressures typically range from 5 to 10 cm H2O. Effective and safe use of the bubble CPAP system requires skilled nurses and respiratory therapists.

Preparation

In the out-of-hospital setting, patients initiating CPAP therapy should first be monitored in a sleep laboratory, where a technologist manually titrates pressure settings to determine the optimal level for minimizing apneic events. A sleep clinician or pulmonologist may assist in selecting a well-fitting mask, trialing a humidifier chamber, or choosing a CPAP device with multiple or auto-adjusting pressure settings. Consistent use during overnight sleep and daytime naps is essential for patients using CPAP at home.

Some CPAP units feature a timed pressure ramp, which initiates airflow at a lower level and gradually increases it to the prescribed pressure, enhancing patient comfort during adaptation. Pressure should be titrated appropriately, particularly in chronic conditions such as obstructive sleep apnea, where fixed pressure is the first-line approach. This titration is typically guided by visual confirmation of eliminated respiratory events and residual flow limitation, often achieved by adjusting pressure in 2 cm H2O increments starting at 5 cm H2O.[16] Alternative options include autotitrating CPAP, commonly operating between 5 and 15 cm H2O, or empirical titration based on actual body weight when autotitration is unavailable. These machines use pressure transducer sensors and computer algorithms to adjust pressure in real time to eliminate apneic events automatically.

Complications

The first few nights on CPAP may be challenging as patients adjust to the therapy. Many initially find the mask uncomfortable, claustrophobic, or embarrassing. Adverse events from CPAP treatment can include congestion, a runny nose, dry mouth, or nosebleeds, with humidification often alleviating these symptoms. Masks may cause skin irritation or redness. Using the correct size mask and adequate padding can help prevent pressure sores. The mask and tubing should be cleaned regularly, inspected, and replaced every 3 to 6 months. Abdominal distension or bloating may occur, rarely leading to nausea, vomiting, and aspiration. These issues may be minimized by reducing pressure or, in hospitalized individuals, performing gastric decompression through a tube.

Compliance

Despite the many benefits of CPAP therapy, compliance remains a significant challenge in both inpatient and outpatient settings. Patient compliance should be closely monitored, especially during the initiation of the treatment, to ensure long-term success.[17] Patients must report any adverse events that may limit compliance, which should be promptly addressed. Ongoing follow-up with an annual office visit is essential to check the equipment, adjust settings as needed, and ensure proper mask and interface fit. Continued patient education on the importance of regular use and support group involvement can help maximize CPAP therapy's benefits.

In rare instances, those hospitalized may greatly benefit from CPAP but may not tolerate the mask or comply due to delirium, agitation, or age-related factors in children or older adults. In these cases, mild sedation with low-dose fentanyl or dexmedetomidine can help improve compliance until CPAP therapy is no longer needed. However, close monitoring is critical, as sedatives or anxiolytics can decrease consciousness and respiratory drive. If adequate minute ventilation and oxygenation are not achieved, escalation to bilevel positive airway pressure or intubation with mechanical ventilation should be considered, per the patient’s code status and care goals.

Clinical Significance

CPAP is a widely used mode of PEEP delivery in both hospital and outpatient settings, including home therapy for sleep apnea.[18] The benefits of initiating CPAP include improved sleep quality, reduction or elimination of snoring, and decreased daytime sleepiness. Many patients report enhanced concentration, memory, and cognitive function. CPAP can also alleviate pulmonary hypertension and reduce blood pressure. The treatment is safe for patients of all ages, including children.

CPAP improves V/Q matching and helps maintain functional residual capacity. Unlike invasive mechanical ventilation, CPAP avoids complications, such as excessive sedation and risks of volutrauma and barotrauma. In the inpatient setting, CPAP therapy requires close monitoring with regular assessment of vital signs, blood gases, and clinical status. Mechanical ventilation should be considered if signs of clinical deterioration are evident.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

CPAP is commonly prescribed by primary care providers, nurse practitioners, internists, and neurologists for patients with obstructive sleep apnea. However, good compliance hinges on thorough patient education. Many patients discontinue use shortly after initiation due to discomfort. Although CPAP is an effective temporary treatment for OSA, it does not reduce the risk of cardiac complications. Patients should also be encouraged to lose weight, adopt a healthy diet, quit smoking, and exercise regularly to improve overall health outcomes.[19]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Airway Pressure Release Ventilation Pressure Cycles with Superimposed Spontaneous Breathing. Airway Pressure Release Ventilation (APRV) is a mode of mechanical ventilation that combines sustained high airway pressure with periodic brief releases to lower pressure, functioning as a form of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). P-high represents the CPAP level, and T-high indicates the duration of P-high. During APRV, the CPAP phase (P-high) is periodically released to P-low for a brief period (T-low), after which the CPAP level is reestablished on the next breath. Spontaneous breathing can occur at both pressure levels and is independent of time cycling.

Habashi NM. Other approaches to open-lung ventilation: airway pressure release ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(3 suppl):228-240. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000155920.11893.37.

References

Gupta S, Donn SM. Continuous positive airway pressure: Physiology and comparison of devices. Seminars in fetal & neonatal medicine. 2016 Jun:21(3):204-11. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2016.02.009. Epub 2016 Mar 3 [PubMed PMID: 26948884]

Gong Y, Sankari A. Noninvasive Ventilation. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 35201716]

Sankri-Tarbichi AG, Rowley JA, Badr MS. Expiratory pharyngeal narrowing during central hypocapnic hypopnea. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2009 Feb 15:179(4):313-9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200805-741OC. Epub 2008 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 19201929]

Alchakaki A, Riehani A, Shikh-Hamdon M, Mina N, Badr MS, Sankari A. Expiratory Snoring Predicts Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Patients with Sleep-disordered Breathing. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2016 Jan:13(1):86-92. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201507-413OC. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26630563]

Brockbank JC. Update on pathophysiology and treatment of childhood obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Paediatric respiratory reviews. 2017 Sep:24():21-23. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2017.06.003. Epub 2017 Jun 12 [PubMed PMID: 28697968]

Cross TJ, Kim CH, Johnson BD, Lalande S. The interactions between respiratory and cardiovascular systems in systolic heart failure. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985). 2020 Jan 1:128(1):214-224. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00113.2019. Epub 2019 Nov 27 [PubMed PMID: 31774354]

Mora Carpio AL, Mora JI. Positive End-Expiratory Pressure. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28722933]

Hickey SM, Sankari A, Giwa AO. Mechanical Ventilation. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969564]

Gupta S, Donn SM. Continuous Positive Airway Pressure: To Bubble or Not to Bubble? Clinics in perinatology. 2016 Dec:43(4):647-659. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2016.07.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27837750]

Polin RA, Sahni R. Newer experience with CPAP. Seminars in neonatology : SN. 2002 Oct:7(5):379-89 [PubMed PMID: 12464500]

Gottlieb DJ, Punjabi NM, Mehra R, Patel SR, Quan SF, Babineau DC, Tracy RP, Rueschman M, Blumenthal RS, Lewis EF, Bhatt DL, Redline S. CPAP versus oxygen in obstructive sleep apnea. The New England journal of medicine. 2014 Jun 12:370(24):2276-85. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306766. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24918372]

Rana AM, Sankari A. Central Sleep Apnea. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 35201727]

Bradley TD, Logan AG, Kimoff RJ, Sériès F, Morrison D, Ferguson K, Belenkie I, Pfeifer M, Fleetham J, Hanly P, Smilovitch M, Tomlinson G, Floras JS, CANPAP Investigators. Continuous positive airway pressure for central sleep apnea and heart failure. The New England journal of medicine. 2005 Nov 10:353(19):2025-33 [PubMed PMID: 16282177]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBrown LK, Javaheri S. Positive Airway Pressure Device Technology Past and Present: What's in the "Black Box"? Sleep medicine clinics. 2017 Dec:12(4):501-515. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2017.07.001. Epub 2017 Sep 18 [PubMed PMID: 29108606]

Casey JL, Newberry D, Jnah A. Early Bubble Continuous Positive Airway Pressure: Investigating Interprofessional Best Practices for the NICU Team. Neonatal network : NN. 2016:35(3):125-34. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.35.3.125. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27194606]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePatil SP,Ayappa IA,Caples SM,Kimoff RJ,Patel SR,Harrod CG, Treatment of Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea with Positive Airway Pressure: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2019 Feb 15; [PubMed PMID: 30736887]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSchwab RJ, Badr SM, Epstein LJ, Gay PC, Gozal D, Kohler M, Lévy P, Malhotra A, Phillips BA, Rosen IM, Strohl KP, Strollo PJ, Weaver EM, Weaver TE, ATS Subcommittee on CPAP Adherence Tracking Systems. An official American Thoracic Society statement: continuous positive airway pressure adherence tracking systems. The optimal monitoring strategies and outcome measures in adults. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2013 Sep 1:188(5):613-20. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201307-1282ST. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23992588]

Tingting X, Danming Y, Xin C. Non-surgical treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2018 Feb:275(2):335-346. doi: 10.1007/s00405-017-4818-y. Epub 2017 Nov 24 [PubMed PMID: 29177626]

Johnson BP, Shipper AG, Westlake KP. Systematic Review Investigating the Effects of Nonpharmacological Interventions During Sleep to Enhance Physical Rehabilitation Outcomes in People With Neurological Diagnoses. Neurorehabilitation and neural repair. 2019 May:33(5):345-354. doi: 10.1177/1545968319840288. Epub 2019 Apr 2 [PubMed PMID: 30938225]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence