Introduction

Dacryocystitis is the most commonly encountered disease of the lacrimal drainage system.[1] This disease is an inflammation of the lacrimal sac, typically caused by an obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct (NLD), leading to the stagnation of tears in the lacrimal sac. Dacryocystitis patients complain of watering from the affected eye and distension of the lacrimal sac, visible below the medial canthus. Other common presenting symptoms can be redness or pain along the distended lacrimal sac. While it can appear as a pretty minor condition at presentation to the clinicians, it can have devastating complications like abscess formation, orbital cellulitis, loss of vision, or cavernous sinus thrombosis if not treated appropriately.

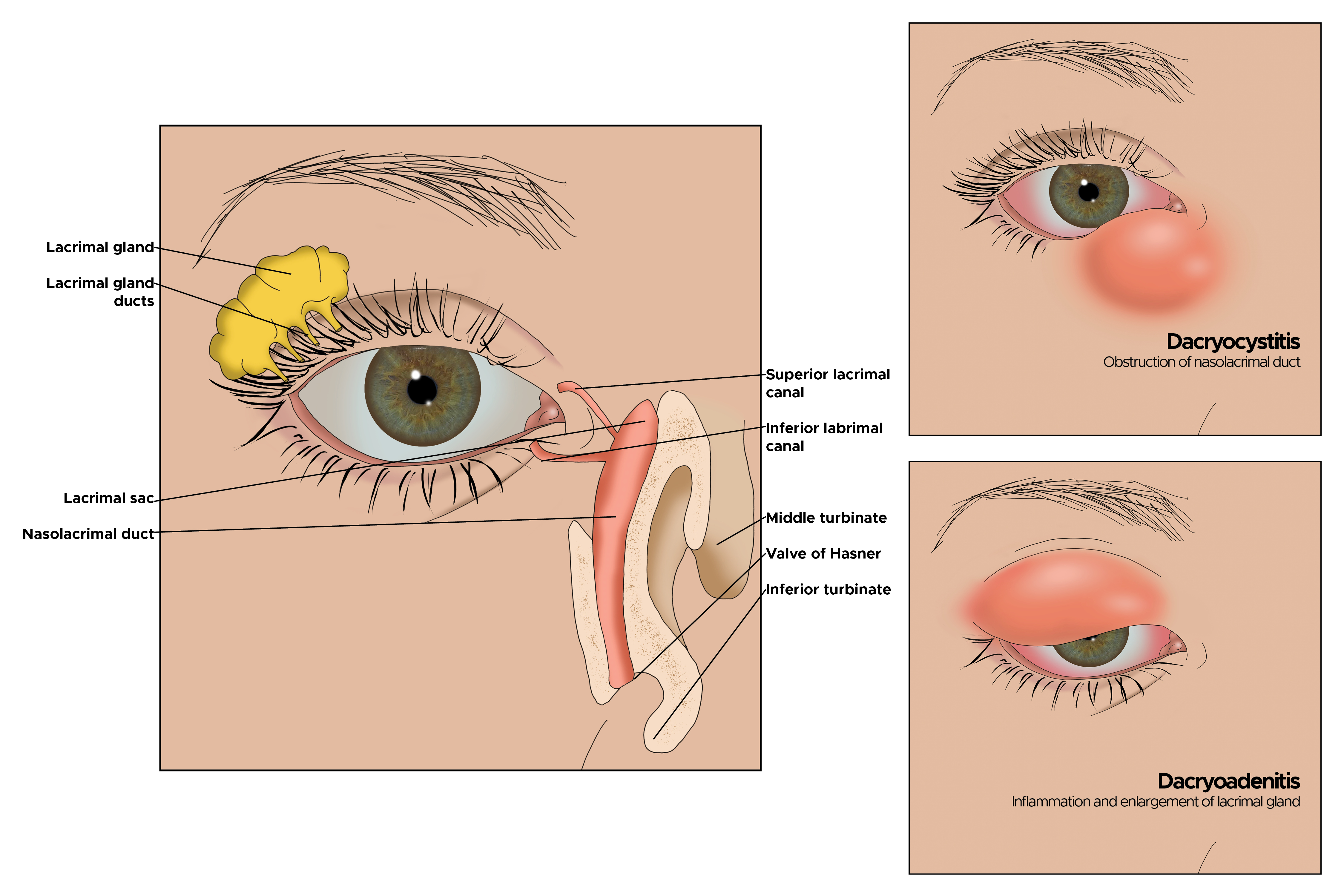

Understanding the anatomy and flow of tears can help better understand dacryocystitis and potential treatment options. Aqueous tear production begins in the lacrimal gland. The tears are spread over the ocular surface with blinking of the eyelids, thus lubricating the eye. The tears are collected by the superior and inferior puncta and drained into the respective canaliculi. The tears further flow into the common canaliculus, then through the valve of Rosenmuller into the lacrimal sac. The collected tears travel down the NLD, passing through the distal valve of Hasner, and ultimately drain into the inferior meatus of the nasal cavity. The fibres of the orbicularis oculi muscle surround the canaliculi and the lacrimal sac. The contraction and relaxation of the pretarsal orbicularis muscle contribute to the mechanical pumping action, aiding in tear drainage. Failure of the pretarsal fibres of the orbicularis muscle can cause failure of the physiological pumping action for tear drainage.[2] This leads to persistent tearing in the absence of an anatomical blockage or dacryocystitis.

The earliest mention of the disease is found in the works of Hippocrates and von Galen, who described a conventional management strategy for dacryocystitis. The first definitive surgical treatment was suggested by Toti in the form of a dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) in 1904.[3] This approach has since undergone numerous modifications and refinements to the current advanced management modalities.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Dacryocystitis can be classified as:

- Acute dacryocystitis

- This form is an active suppuration of the lacrimal sac. Worldwide, the most common organisms isolated in these cases are Streptococcus pneumoniae, followed by Staphylococcus sp., other Streptococcus species, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.[4] The suppuration can often spread from the sac to the surrounding tissues, forming a lacrimal abscess. The history of less than 3 months is categorised as acute dacryocystitis. An incomplete resolution of acute disease with persistent infection leads to subacute dacryocystitis.

- Chronic dacryocystitis

- This form results from a long-standing obstruction of the NLD, and is often due to repeated attacks of acute infection, idiopathic fibrosis of the NLD, systemic diseases, persistent dacryoliths, and chronic inflammatory debris in the nasolacrimal system. The duration of the disease is usually more than 3 months.

The underlying NLD obstruction can be classified as:

- Congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction (cNLDO)

- In the congenital form, the obstruction is due to a membranous obstruction at the valve of Hasner in the distal NLD. The other causes for cNLDO are incomplete canalization of the NLD, developmental cranofacial anomalies, and syndromic causes like Down syndrome, Goldenhar syndrome, Crouzon syndrome, and Treacher-Collins syndrome.[5] cNLDO cases can often present with bilateral disease. Neonatal dacryocystitis is a rare entity, where cNLDO leads to acute dacryocystitis and abscess formation during the first month of life. Neonatal cases may also present as bluish cystic swelling below the medial canthus, mimicking an encysted mucocele. This is called a congenital dacryocystocele.

- Acquired nasolacrimal duct obstruction (ANDO)

- The acquired form can be primary (PANDO) or secondary (SANDO) obstruction of the NLD. PANDO usually comprises idiopathic obstruction of the lacrimal drainage pathway at the junction of the lacrimal sac and NLD. SANDO encompasses NLD obstruction, typically due to repeated trauma, surgeries, long-term medications, and neoplasms.

- The traumatic causes of NLD obstruction commonly include nasoorbitoethmoid and Le-Fort type 2 fractures, followed by lacrimal and maxillary bone fractures. Nasal, endonasal, and endoscopic sinus surgeries are associated with SANDO.

- Common topical medications responsible for SANDO are timolol, pilocarpine, dorzolamide, idoxuridine, and trifluridine. The most common systemic medications implicated in SANDO cases are 5-fluorouracil, docetaxel, and radioiodine therapy for thyroid neoplasms.

- Primary lacrimal sac tumors can also cause SANDO. They are commonly benign papillomas or malignancies, such as squamous cell carcinoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, or melanoma. Tumors originating from adjacent tissues, such as sinonasal carcinomas, can invade the NLD and lead to SANDO.

- Infectious etiologies such as tuberculosis, leprosy, fungal infections, as well as inflammatory pathologies like granulomatosis with polyangitis, sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and chronic allergic rhinosinusitis, can be responsible for bilateral SANDO.

Anatomical variations of the lacrimal sac, such as diverticula, sacculations, or a large sac, may cause stagnation of tears and infectious pathologies, despite a patent lacrimal drainage pathway.

Epidemiology

cNLDO usually presents in infancy, with up to 10% of all live-birth neonates affected at birth.[6] Premature birth is a known risk factor for cNLDO.

Acquired dacryocystitis exhibits a bimodal age distribution, the peak involvement being in early adulthood and middle age, typically after 40 years of age.[7] PANDO exhibits a female predisposition, with nearly 75% of cases reported in women. This is likely due to a narrower bony NLD, increased tortuosity of the membranous NLD, and a higher predisposition to lacrimal sac mucosal atrophy during postmenopausal hormonal changes.[8] The incidence is higher among rural communities with restricted access to hygiene and healthcare. Seasonal variation is also observed, with flare-ups of acute dacryocystitis during upper respiratory tract infections in the winter. Serious morbidity and mortality are low in dacryocystitis cases. Associated conditions like deviated nasal septum, diabetes mellitus, immunocompromised states (HIV, long-term immunosuppression), and chronic rhinosinusitis can worsen the ocular morbities.

Pathophysiology

Dacryocystitis is caused by a partial or complete obstruction in the nasolacrimal drainage system, resulting in the stagnation of tears in the lacrimal sac. Such obstructions can occur at any level of the lacrimal drainage pathway, most commonly at the junction of the lacrimal sac and NLD. The stagnation of tears creates a favorable environment for infectious organisms to propagate and for proteinaceous debris to form. With progressive inflammation, the lacrimal sac shows the characteristic swelling in the inferomedial portion of the lower eyelid. The stagnation of infectious material in the lacrimal sac causes inflammation of the surrounding tissues below the medial canthus, resulting in acute dacryocystitis. The disease can be staged into presuppurative, suppurative, spontaneous rupture, and complicated disease.[9]

The spread of infection beyond the confines of the lacrimal sac into the pericanthal tissues, accompanied by active suppuration, results in the formation of a lacrimal abscess. Spontaneous rupture of the lacrimal abscess can occur in some cases, forming an acquired lacrimal fistula. The acquired fistula is located at the most dependent part of the lacrimal sac abscess, away from the medial canthus, on the medial aspect of the lower eyelid. The ruptured lacrimal abscess heals with scarring below the medial canthus, forming an acquired fistula in cases of residual or untreated infections.

Chronic dacryocystitis has been staged into catarrhal, mucocele, chronic granulation, and complicated disease. The distention of the lacrimal sac with mucoid contents causes the formation of a mucocele. Secondary infection of the mucocele causes accumulation of purulent contents, characterized by pyocele formation. Occasional cases of mucocele develop a membranous obstruction at the level of the common canalicular opening, leading to encysted mucocele formation.

Histopathology

The lacrimal sac has a lining of pseudostratified columnar epithelium in normal cases. The presence of lymphoid tissue in the subepithelial area is often regarded as a continuation of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue.[10]

In cases of acute dacryocystitis, histopathology of the sac wall shows neutrophilic infiltration with pus cells, dilated capillaries, and granulation tissue. The lacrimal sac wall in chronic dacryocystitis characteristically shows nongranulomatous lymphocytic inflammation, thickening of the sac wall, and subepithelial fibrosis.[11] The involvement of the lacrimal sac in systemic diseases like sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, rheumatoid arthritis, or other autoimmune disorders exhibits disease-specific histopathological features. Idiopathic dacryocystitis or PANDO can show epithelial squamous metaplasia, subepithelial fibrosis, and chronic lymphocytic infiltrate.[11] The cases of lacrimal sac neoplasms show specific diagnostic features for the respective malignancies.

History and Physical

In acute dacryocystitis, symptoms may occur over several hours to several days. A detailed history is the primary step in the evaluation. The exact duration of the complaints of watering, pain, discharge, and swelling must be noted. The association of episodes of common cold, sinusitis, or nasal congestion is often seen in cases of acute dacryocystitis. The presence of extreme pain with yellowish discolouration of the overlying skin suggests a lacrimal abscess. A history of trauma or nasal surgery that may have led to the current condition must be obtained.

A careful ophthalmological examination must be performed. The medial canthus overlying the lacrimal space must be examined for tenderness or pain, graded on a visual analogue Likert scale. The presence of erythema and a local rise in temperature suggests an active underlying infection. The presence of a discharging fistula or scarring below the medial canthus is a result of recurrent attacks of acute dacryocystitis. The bridge of the nose may also be involved; however, the involvement of the superior aspect of the medial canthus is unlikely. Upon compression of the sac swelling, regurgitation of mucopurulent material from the superior and inferior puncta is commonly noted. This test is called the regurgitation test or regurgitation on pressure over the lacrimal sac area (ROPLAS) test. The assessment of the punctum and the canaliculus is imperative to rule out any stenosis or membranous obstruction. Acute disease can often present with punctual edema, characterized by oozing pus from the inflamed punctal orifice.

In chronic dacryocystitis, profuse tearing may be the only symptom. This is called epiphora. Epiphora is graded using the Munk score. Another characteristic finding is matting of the eyelashes due to persistent shedding of mucoid contents into the tear film.

For all cases of dacryocystitis, assessing the visual acuity, pupillary reactions, extraocular eye movements, and fundus examination is imperative. Any acute changes on ophthalmological examination not explained by raised tear film should raise concern for more extensive infection. The red flag signs on external examination that should alarm the clinician include swelling and erythema involving the upper eyelid or cheek, extensive conjunctival congestion, retrobulbar pain, limitation of extraocular movements, onset of proptosis or diplopia, and unexplained diminution of visual acuity. Emergent oculoplasty consultation is warranted in these scenarios.

Certain red flag signs to be looked out for during evaluating and treating dacryocystitis cases, which favour the diagnosis of lacrimal sac malignancies, are:

- No response to standard broad-spectrum antibiotics

- Absence of purulent discharge with associated presentation of acute dacryocystitis

- Blood-stained discharge

- Bloody regurgitation on the ROPLAS test

- Firm to hard mass, with fixity to the underlying bone

- Failure of DCR surgery in the early phase (<1 month)

- Neck or generalized lymphadenopathy, or constitutional symptoms [12][13]

Evaluation

The diagnosis of dacryocystitis is primarily based on history and clinical examination findings. The basic clinical workup checklist should include the following:

- Best corrected visual acuity

- External examination of eyelids, medial canthus, and eyelashes

- Punctum and canaliculus examination

- ROPLAS test

- Ocular surface examination, including meibomian glands, conjunctiva, and cornea

- Tear film assessment

- Tear meniscus height (TMH) and tearfilm breakup time (TBUT)

- Anterior and posterior segment examination

- Extraocular movement examination

- Syringing and probing, when indicated

- Fluorescein dye disappearance test (FDDT)

Syringing and probing are done under topical anesthesia. A lacrimal cannula or probe is inserted through the punctum, following the course of the canaliculus to assess patency of the canalicular passage. Lacrimal probing is used to localise the site of block accurately in millimeters, for cases of proximal, distal, or common canalicular blocks. The syringing findings are described as:

- Freely patent

- When there is a free flow of saline into the lacrimal drainage pathway, and the subject can appreciate the fluid in the nose and/or throat, suggesting a patent passage

- Regurgitation from the same punctum

- When there is regurgitation of fluid due to proximal/distal canalicular block

- Regurgitation from the opposite punctum

- When there is regurgitation of fluid due to common canalicular block or NLD obstruction

- Stenosed punctum

- When there is a punctal block with the inability to pass the cannula or probe through the punctum

- Nature of regurgitation fluid

- Whether the regurgitation fluid is clear, mucoid, mucopurulent, or frankly purulent, it suggests the exact stage of disease.

FDDT is an important noninvasive test, especially for pediatric dacryocystitis patients, cNLDO cases, or mentally challenged individuals who are not cooperative for lacrimal syringing. After adequate topical anesthesia, a drop of fluorescein dye is instilled in both eyes. After 5 minutes, the residual dye in the tear lake is compared. Persistence of the dye beyond 5 minutes is a sign of obstruction. Cases with severe epiphora show a dye rundown over the cheek.

Nasal endoscopy is often an essential part of the clinical workup. The otorhinolaryngologist or a trained oculoplasty surgeon must examine for coexisting nasal pathologies such as nasal polyps, a deviated nasal septum, turbinate hypertrophy, atrophic rhinitis, signs of nasal trauma or past nasal surgeries, inflammatory sinus pathologies, fungal infections, or sinonasal malignancies. Endonasal examination also assesses the adequacy of the nasal cavity for future endonasal DCR surgery.

Among cases with acute dacryocystitis, the priority is to initiate empirical antibiotic therapy. However, an accurate diagnosis of the causative organism is essential for focused therapy before definitive surgical intervention. The lacrimal sac is gently massaged to express the purulent contents, which are then sent for Gram staining, culture, and antibiotic sensitivity. Laboratory studies and blood cultures are often essential in patients with fever, proptosis, diplopia, limited extraocular movements, or acute visual changes. Urgent oculoplasty consultation is needed in these cases. These patients also require radioimaging of the orbits and paranasal sinuses, in the form of computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, to rule out the possibility of orbital cellulitis.

If there are anatomical concerns, a plain-film dacryocystogram (DCG) can be performed by qualified personnel. In this process, a water-soluble, nonionic contrast such as Iohexol is injected through the punctum, using a lacrimal cannula, followed by imaging techniques like x-ray or CT scan. DCG is useful in cases with uncertain diagnosis, lacrimal sac diverticula or sacculations, failed DCR surgeries, posttraumatic SANDO cases, and lacrimal neoplasms. A subtraction CT-DCG with 3-dimensional (3D) reconstruction helps improve the treatment planning, especially before endonasal DCR surgery.[14] DCG, however, doesn't provide information about physiological tear drainage. Dacryoscintigraphy (DCS) is a newer imaging modality in which a nuclear medicine expert instills a 99m-technetium-labelled tracer into the forniceal tear lake before imaging with a gamma camera. This helps determine the tear drainage with blinking and assess functional blocks. The combination of DCG-DCS can provide a comprehensive overview of the etiology of epiphora.

In chronic cases, appropriate serologic testing can be performed if systemic diseases are suspected as the underlying cause. Antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody testing can be performed if granulomatosis with polyangitis is suspected. Likewise, antinuclear antibody (ANA) testing can be pursued if systemic lupus erythematosus is suspected.

Treatment / Management

Congenital Dacryocystitis

The treatment starts as early as possible, at the first visit to the clinician. Conservative measures such as Criggler massage are the first line of management. Parents or caregivers can be trained to perform lacrimal massage at home, using the correct technique, applying adequate pressure, and doing the massage regularly. Compliance and response to massage must be ensured at monthly or 2-monthly follow-up visits. Topical antibiotics can be considered for acute flares or severe discharge with eyelash matting. Approximately 90% of cNLDO cases tend to resolve by 6 to 12 months of age with conservative therapy alone.[15](B2)

If conservative measures fail, a referral is made to an oculoplasty specialist for endoscopy-guided nasolacrimal probing. The conventional management protocols dictate that probing is advised after 12 to 18 months of age.[15] Recent literature indicates success after intervention in cases as young as 9 to 12 months of age.[16] Nasolacrimal probing should be performed under adequate endoscopic endonasal visualization to identify the site of the blockage correctly. The most common etiology is a soft membrane at the valve of Hasner, which can be forcibly broken using the tip of the lacrimal probe. Some cases have a thick membrane in the inferior meatus of the nose, which needs to be perforated using a sharp sickle knife. Rare cases may present with bony obstruction, which would require more extensive management. Nasolacrimal probing is successful in more than 70% to 90% of cases. The probing can be repeated if symptoms recur. The advent of nasolacrimal intubation in failed probing cases has improved success rates to around 95% of cases. Another treatment modality, with variable success rates, is balloon dacryoplasty, where a catheter is passed down the NLD and a balloon is inflated to dilate the existing passage. (B2)

If these measures fail, then DCR will serve as the definitive treatment, usually planned after 4.5 to 5 years of age. Newer advances recommend the use of endoscopic endonasal DCR surgery to provide a successful and scarless surgical option for children with cNLDO. DCR in the pediatric population offers greater surgical challenges, with higher rates of failure. The use of adjuncts, such as antifibrotic agents (mitomycin-C) or silicone tube intubation, has improved surgical success rates, resulting in better symptom resolution in long-term follow-up.

Certain conditions that warrant an urgent surgical intervention for cNLDO, irrespective of the age at presentation, are:

- Coexisting congenital ocular anomalies like cataract and glaucoma, needing surgery

- Coexisting retinal disorders like retinopathy of prematurity and retinoblastoma, which need surgery

- Congenital ocular surface disorders predisposing the cornea to recurrent infections

- Recurrent acute dacryocystitis in infancy or early childhood

- Acute lacrimal abscess in early childhood

- Formation of a dacryocystocele

Acute Dacryocystitis

The initial management includes conservative measures such as warm compresses, starting oral empirical broad-spectrum antibiotics, oral analgesics, and topical antibiotic eyedrops. The spectrum of antibiotic coverage should be tailored to include common organisms such as gram-positive cocci, particularly Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species. The usual oral drugs prescribed are amoxicillin-clavulanate, cefuroxime, or ciprofloxacin, depending on the local antibiotic sensitivity patterns. Syringing and lacrimal probing are contraindicated in cases of acute inflammation. The natural history of disease is the resolution of the acute episode within 3 to 7 days, accompanied by persistence of watering and discharge. Acute flare-ups are often noted every few months due to persistent residual infection in the lacrimal sac.

The formation of fluctuant or tense swelling suggests progression to lacrimal abscess. All acute cases must be referred to an ophthalmologist or oculoplasty surgeon for timely planning of the surgical intervention. Incision and drainage of the abscess are imperative at this stage, along with the use of appropriate oral antibiotics and wound hygiene. Delay in definitive surgery after drainage of the abscess can lead to the formation of an acquired lacrimal fistula or healing with extensive cutaneous scarring.[17] Conventional protocols dictate a waiting period of at least 4 weeks before planning an external DCR surgery. This wait period allows the skin and surrounding tissues to heal adequately before the next surgery. Recent studies show good outcomes with an immediate endonasal DCR surgery. This procedure is scarless and provides relief from swelling and pain, with resolution of the infection, and opens up an alternative pathway for tear drainage. The timing of the surgery must be tailored to the patient's age, clinical presentation, systemic comorbidities, stage of acute disease, and compliance with treatment. The onset of orbital cellulitis, cavernous sinus thrombosis, a debilitated state of the patient, or septic shock are definite contraindications to an urgent DCR surgery.

Chronic Dacryocystitis

The management plan depends on the severity of epiphora. Patients with low Munk scores, nil discharge, and minimal or no swelling can be managed conservatively with regular follow-ups. Syringing and probing are accepted as first-line management in chronic cases and can be done in the outpatient setting. Probing helps the clinician accurately localise the site of blockage in the canaliculi or sac, to aid adjunctive measures during the surgery. When a soft stop is encountered in the proximal (<4-5 mm) or distal canalicular system (at 5-10 mm), an associated canalicular block must be suspected. A soft stop between 10 and 12 mm suggests a common canalicular block, often seen with pericanalicular stenosis and in cases of encysted mucocele. Such patients need surgical recanalisation of the obstructed canalicular pathway with in situ stenting to establish a patent pathway. The patients with dacryocystitis often show a patent canalicular passage with a bony hard stop at >14 mm on probing. Such patients with bothersome epiphora, an enlarged sac, and persistent discharge require a definitive DCR surgery.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses need to be tailored as per the presenting complaints. For patients presenting with epiphora and discharge, the commonly associated disorders to be ruled out include:

- Uncorrected refractive errors

- Eyelid lash abnormalities - trichiasis, distichiasis

- Eyelid margin malposition - ectopion and entropion

- Punctal pathologies - punctal ectropion, punctal stenosis

- Dry eye disease

- Meibomian gland dysfunction

- Mucus fishing syndrome

- Lagophthalmos and paralytic ectropion, with facial nerve palsy

- Floppy eyelid syndrome

- Recurrent sinusitis - frontal (commonly), ethmoid, or maxillary

Among patients presenting with a swelling below the medial canthus, the common differentials include:

- Sebaceous cyst

- Dermoid at the medial canthus

- Lacrimal neoplasms

- Maxillary sinus neoplasms

- Congenital meningocele, meningoencephalocele, or encephalocele

- Nasal bone fractures with displacement of bony fragments

The differentials for acute dacryocystitis include:

- Acute conjunctivitis

- Canaliculitis

- Infected sebaceous cyst

- medial orbital abscess

- Acute infection in SANDO cases - due to neoplasms or trauma

- Mucormycosis

The cNLDO cases offer up a wide possibility of differentials which must be ruled out, in addition to the already listed causes:

- Congenital glaucoma

- Congenital corneal dystrophies

- Intraocular malignancies like retinoblastoma

Treatment Planning

DCR surgery is a technique to create direct communication between the obstructed lacrimal sac and the middle meatus of the nose. DCR is currently considered the gold standard treatment modality for patients with dacryocystitis. The 2 major types of DCR described in the literature are external and endoscopic endonasal techniques.

External DCR involves a J-shaped skin incision below the medial canthus along the tear trough of the lower eyelid. The orbicularis oculi muscle is split along its fibers to expose the periosteum over the frontal process of the maxilla. The periosteum is incised and reflected to expose the anterior lacrimal crest, lacrimal sac fossa, and the posterior lacrimal crest. The bony osteotomy is initiated below the posterior lacrimal crest and advanced anteriorly and superiorly to create an adequate bony opening. The limits of bony osteotomy are the medial canthal tendon superiorly, the opening of the NLD inferiorly, suture with the lamina papyracea posteriorly, and as far as possible anteriorly without damaging the bridge of the nose. The exposed nasal mucosa of the middle meatus is then incised to create a flap. The lacrimal sac is similarly opened with the creation of flaps. The posterior flaps of the lacrimal sac and the nasal mucosa are then excised, and free passage of the lacrimal cannula or probe is assessed to confirm patency of the newly created passage. The anterior sac flap is sutured with the nasal mucosal flap and hitched to the overlying orbicularis oculi muscle. The wound is closed in layers. Commonly used adjuncts during the surgery are antifibrotic agents like mitomycin-C and mechanical stents like silicone intubation tubes to maintain long-term patency and boost the success rate of DCR surgery. The advantages of external DCR surgery are direct visualisation of the obstructed lacrimal drainage pathway, easy manipulation and excision of the enlarged lacrimal sac, and higher success rates. However, external DCR leaves a skin scar below the medial canthus. Recent developments have introduced the mini-incision DCR surgery and the use of a powered microdrill for osteotomy, with comparable success rates.[18]

Endoscopic endonasal DCR is a scarless surgery, an advancement over the external DCR. Here, the surgery is initiated from the middle meatus of the nasal cavity with an incision on the nasal mucosa. The mucosa and periosteum are reflected to reveal the lacrimal bone and the frontal process of the maxilla. The osteotomy is created using Endonasal Kerrison bone punches. The lacrimal sac is prolapsed through the osteotomy into the nasal cavity and opened in a textbook fashion to drain the sac contents into the nasal cavity. The nasal mucosal flap is trimmed adequately and apposed to the lacrimal sac flaps. Silicone tube intubation is often used to provide patency to the pathway for sustained long-term results. The advantages of endonasal DCR are a minimally invasive, scarless approach with a shorter healing time and concurrent management for intranasal pathologies. The disadvantages are a steep learning curve and difficulty during surgical manipulation in cases with an altered nasal anatomy, such as post-trauma and previously failed DCR surgery.

Pediatric DCR surgery is more complicated than adult cases. The commonly encountered difficulties are a smaller anatomical space for surgical manipulation, poorly defined anatomical landmarks, softer facial bones making osteotomy difficult, anteriorly placed ethmoidal air cells, and smaller lacrimal sac flaps. An experienced ophthalmologist or oculoplasty surgeon must be consulted for the planning of pediatric surgical interventions.

The cases with a soft stop on probing, suggestive of canalicular blocks, require a conjunctivo-DCR surgery, where the blocked canaliculi are bypassed and a direct communication is established between the medial fornix and the middle meatus. An acquired lacrimal fistula may need an additional fistulectomy to ensure complete excision of the epithelialized tract and prevent recurrence. This is done via an external approach that involves excision of the fistula tract through a spindle-shaped skin incision to induce minimal scarring. Patients with lacrimal sac malignancies masquerading as dacryocystitis need a detailed evaluation and planning of treatment by a team of oculoplasty surgeons, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, maxillofacial surgeons, and otorhinolaryngologists.

Staging

The stages of acute dacryocystitis are:

- Presuppurative (inflammatory) phase

- Bacterial colonization begins in the stagnant tears resulting from NLD obstruction, accompanied by mucosal edema. The presentation is epiphora, sac swelling, occasional pain, and redness. Management includes warm compresses, analgesics, and oral empirical/broad-spectrum antibiotics. Syringing can be painful and is best avoided here.

- Suppurative (abscess) phase

- Pus forms in the lacrimal sac, affecting the surrounding tissues. The patient develops intense pain and swelling below the medial canthus, with tense cystic swelling and pus oozing over the skin. Toxic look and fever are also noted. Careful ophthalmology evaluation is essential at this stage. Radioimaging, like a CT scan, would show a localised abscess in the lacrimal sac. The treatment involves pus culture, oral or intravenous antibiotics, and adequate analgesia. In cases of a threatened rupture of the lacrimal abscess, a planned incision and drainage are recommended. These patients will require a definitive DCR surgery in the future.

- Fistula formation (spontaneous drainage) phase

- The tense lacrimal abscess ruptures through the skin, forming a persistent discharging sinus or fistula on the overlying skin. The patient complains of excoriation of the surrounding skin with pus discharge and thickening of the overlying tissues. Scar formation with healing is often noted. An urgent referral to an oculoplasty specialist is advised at this stage. The treatment involves DCR surgery with excision of the fistulous tract (fistulectomy).

- Complications phase

- The commonly encountered complications are encysted pyocele (phlegmon), orbital cellulitis, cavernous sinus thrombosis, and sepsis. These complications can often be life-threatening and require emergency evaluation and management. Radioimaging of the orbit, brain, and paranasal sinuses is required to assess the extent of the disease. The patient would require immediate hospitalization, with intravenous antibiotics and supportive management. [9]

The stages of chronic dacryocystitis are:

- Catarrhal (early inflammation) phase

- The NLD obstruction cases mucosal hypertrophy with stasis of mucoid contents and tears, and colonization of bacteria. The patient complains of epiphora, ocular discomfort, and discharge, with a positive ROPLAS test. The management starts with topical antibiotics and a definitive DCR surgery if symptoms persist.

- Mucocele formation

- The progressive dacryocystitis causes sac distension with occasional exacerbations. The ROPLAS test is positive, with frank regurgitation of mucoid flakes from the opposite punctum on attempted syringing, and a definite hard stop on probing. The management includes definitive DCR surgery at the earliest.

- Chronic (granulomatous) phase

- Chronic stasis of mucoid debris causes fibrosis and foreign body granulomatous reaction in the lacrimal sac wall. This phase may present with infrequent epiphora, with a negative ROPLAS test, due to a dry, shrunken sac. The findings on syringing show clear fluid regurgitation from the opposite punctum with a definite hard stop on probing. DCR is mandatory at this stage to relieve the block.

- Sequelae and complications phase

- The common sequelae are encysted mucocele and lacrimal sac sacculations. Chronic inflammation in the sac may cause a membrane formation at the common canalicular opening, resulting in the mucocele being closed at both ends, forming an encysted mucocele. The patient shows a sac swelling with epiphora, with the ROPLAS test negative. The treatment at this stage comprises DCR surgery with excision of the distended sac and adjunctive silicone intubation to prevent failure of surgery. Chronic distension of the lacrimal sac may cause acquired sacculations or diverticulum formation, with spread of the disease into adjacent tissues. The DCR surgery may be difficult in these situations due to septations within the lacrimal sac, which may cause residual infection post-definitive surgery.

Prognosis

In general, the prognosis for dacryocystitis is good. Simple probing techniques are highly successful for congenital NLDO. DCR has been reported to be more than 93% to 97% successful.[19] In congenital cases, approximately 90% will resolve with conservative measures alone by the age of 1. The outlook for most adult patients with PANDO is good, but for SANDO cases, the outcomes are guarded and can interfere with vision and lifestyle.

Complications

Congenital dacryocystitis can present with an acute flare-up of the infection. Infants and children have a higher risk of spread of infection to orbital cellulitis, cavernous sinus thrombosis, septicemia, and septic shock. These cases must be managed aggressively by the pediatricians under the monitoring of ophthalmologists or oculoplasty surgeons

Acute dacryocystitis in patients on immunomodulation, diabetes mellitus, immunodeficiency, or otherwise immunocompromised status can extend from the lacrimal sac to the surrounding orbital tissues. This can lead to localised abscess, preseptal cellulitis, orbital cellulitis, or orbital abscess. Orbital cellulitis often threatens the orbital apex and optic nerve, resulting in vision loss. Early administration of systemic antibiotics under the expert care of the clinician is advised. Sequelae of acute dacryocystitis, like acquired lacrimal fistula and scarring below the medial canthus, may cause facial disfigurement requiring surgical intervention for rehabilitation.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

The postoperative treatment following DCR surgery includes oral antibiotics, oral analgesics, adequate wound hygiene, and local application of antibiotic ointment on the suture site. The patency of the newly created lacrimal passage can be confirmed by irrigation through the punctum.

Failure of DCR surgery can occur in 5% to 10% of cases, ranging from early to delayed failure.[19] The causes for failure of DCR surgery and recurrence of dacryocystitis can be classified as:

Patient factors:

- Poor compliance with postoperative treatment

- Advanced age

- Increased tendency for scarring or granulation tissue formation

- Preexisting fibrosis at the canaliculus, pericanalicular, or punctal sites

- Undiagnosed lacrimal sac malignancies

- Concurrent nasal pathologies like nasal polyps, atrophic rhinitis, and sinonasal malignancies

- Intranasal adhesions between the septum or turbinates and the osteotomy site

- Recurrent inflammation of the ocular surface, associated with systemic diseases like systemic lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, and tuberculosis

Surgeon factors:

- Wrong site or small size of the osteotomy

- Inadequate size of the flaps, improper apposition of the lacrimal sac and nasal mucosal flaps

- Incomplete excision of the fundus of the lacrimal sac, causing syringing-unrelated mucoid regurgitation from the puncta (SUMP) syndrome

- Leftover bony pieces, bony spurs, or blood clots in the surgical field, inciting secondary inflammation and scarring

For cases with failed DCR surgery, an appropriate referral to the ophthalmologist or oculoplasty surgeon must be made to plan further management. The treatment plans depend on the findings of syringing, probing, and nasal endoscopy. The usual treatment revolves around the release of the scar tissue and adhesions, revision of the osteotomy site, and mechanical stenting of the patent drainage pathway using a silicone tube.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Parents must be aware and take action if their child experiences abnormal discharge from their eyes or shows signs of redness and swelling in the medial canthal area. Delays in the initiation of appropriate treatment due to misdiagnosis or late referral to the clinician must be avoided at the first point of contact. A timely diagnosis can avoid complications threatening the vision, the globe, and life.

Adult or elderly patients with dacryocystitis must also be managed adequately at the first point of contact and referred to a clinician as soon as possible. The patients with dacryocystitis, requiring a concurrent intraocular surgery, have a higher risk of endophthalmitis and surgical site infection. Hence, a definitive DCR surgery is advisable before proceeding with intraocular surgeries for cataract, glaucoma, or vitreoretinal disorders.

Pearls and Other Issues

Disposition from acute care settings depends on the extent of infection, comorbidities, and access to prompt ophthalmological follow-up. Uncomplicated or chronic cases must be advised proper treatment and require adequate follow-up. Acute or complicated cases need an urgent ophthalmology consult and possible inpatient admission for further management. Complications of dacryocystitis, though devastating, can be managed with timely intravenous antibiotics and necessary surgical interventions.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective management of dacryocystitis requires a coordinated, patient-centered approach involving multiple disciplines to ensure timely diagnosis, treatment, and complication prevention. Physicians and advanced practitioners play a central role in early recognition of typical and atypical presentations, identifying red flag signs suggestive of lacrimal sac malignancy, and initiating evidence-based medical or surgical interventions such as antibiotic therapy or dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR). Nurses contribute by monitoring clinical progress, performing wound and periocular care, educating patients on medication use and hygiene, and ensuring adherence to follow-up. Pharmacists support safe and effective antimicrobial therapy by selecting agents tailored to likely pathogens, verifying dosing in special populations, and counseling on potential side effects. Radiologists and pathologists provide essential diagnostic input, particularly in cases requiring imaging or biopsy for suspected malignancy.

Clear, timely interprofessional communication is critical for patient safety and outcome optimization. For example, when initial antibiotic therapy fails, nurses must promptly communicate this to the care team to trigger further investigation. Physicians should share imaging findings and operative outcomes with all team members to guide ongoing care, while pharmacists update the team on culture-directed adjustments. Establishing streamlined referral pathways to ophthalmology, otolaryngology, or oncology ensures rapid escalation when red flags emerge. This collaborative model not only improves diagnostic accuracy and treatment efficacy but also fosters trust, enhances patient education, reduces preventable complications, and strengthens team performance in managing both routine and complex dacryocystitis cases.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Goel R, Golhait P, Khanam S, Raghav S, Shah S, Singh S. Comparative evaluation of dacryocystorhinostomy with retrograde intubation and conjunctivo-dacryocystorhinostomy. Canadian journal of ophthalmology. Journal canadien d'ophtalmologie. 2023 Feb:58(1):39-46. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2021.07.002. Epub 2021 Aug 7 [PubMed PMID: 34370994]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMaliborski A, Różycki R. Diagnostic imaging of the nasolacrimal drainage system. Part I. Radiological anatomy of lacrimal pathways. Physiology of tear secretion and tear outflow. Medical science monitor : international medical journal of experimental and clinical research. 2014 Apr 17:20():628-38. doi: 10.12659/MSM.890098. Epub 2014 Apr 17 [PubMed PMID: 24743297]

Harish V, Benger RS. Origins of lacrimal surgery, and evolution of dacryocystorhinostomy to the present. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology. 2014 Apr:42(3):284-7. doi: 10.1111/ceo.12161. Epub 2013 Aug 4 [PubMed PMID: 23845081]

Luo B, Li M, Xiang N, Hu W, Liu R, Yan X. The microbiologic spectrum of dacryocystitis. BMC ophthalmology. 2021 Jan 11:21(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s12886-020-01792-4. Epub 2021 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 33430825]

Ashby G, Mohney BG, Wagner LH. Incidence and clinical characteristics of congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction with concurrent craniofacial abnormalities among a population-based cohort. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2024 Oct:43(5):583-587. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2024.2348019. Epub 2024 May 26 [PubMed PMID: 38796747]

Sathiamoorthi S, Frank RD, Mohney BG. Incidence and clinical characteristics of congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2019 Apr:103(4):527-529. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-312074. Epub 2018 Jun 6 [PubMed PMID: 29875230]

Khatoon J, Rizvi SAR, Gupta Y, Alam MS. A prospective study on epidemiology of dacryocystitis at a tertiary eye care center in Northern India. Oman journal of ophthalmology. 2021 Sep-Dec:14(3):169-172. doi: 10.4103/ojo.ojo_80_21. Epub 2021 Oct 20 [PubMed PMID: 34880578]

Baybora H, Uysal HH, Baykal O, Karabela Y. Investigating Estrogen and Progesterone Receptors in the Lacrimal Sacs of Individuals With and Without Chronic Dacryocystitis. Beyoglu eye journal. 2019:4(1):38-41. doi: 10.14744/bej.2019.35744. Epub 2019 Apr 16 [PubMed PMID: 35187430]

Ali MJ, Joshi SD, Naik MN, Honavar SG. Clinical profile and management outcome of acute dacryocystitis: two decades of experience in a tertiary eye care center. Seminars in ophthalmology. 2015 Mar:30(2):118-23. doi: 10.3109/08820538.2013.833269. Epub 2013 Oct 30 [PubMed PMID: 24171807]

Goel R, Saini S, Golhait P, Shah S. Association of primary chronic dacryocystitis and meibomian gland dysfunction. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2024 Feb 1:72(2):185-189. doi: 10.4103/IJO.IJO_1449_23. Epub 2023 Dec 15 [PubMed PMID: 38099354]

Amin RM, Hussein FA, Idriss HF, Hanafy NF, Abdallah DM. Pathological, immunohistochemical and microbiologicalal analysis of lacrimal sac biopsies in patients with chronic dacrocystitis. International journal of ophthalmology. 2013:6(6):817-26. doi: 10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2013.06.14. Epub 2013 Dec 18 [PubMed PMID: 24392331]

Chu YC, Tsai CC. Delayed Diagnosis and Misdiagnosis of Lacrimal Sac Tumors in Patients Presenting with Epiphora: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Outcomes. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). 2024 Oct 28:14(21):. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics14212401. Epub 2024 Oct 28 [PubMed PMID: 39518368]

Shah S, Goel R. Epiphora in Treated Lacrimal Drainage System Malignancy Patients - When and Whom to Treat? [Letter]. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2023:17():3463-3464. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S447229. Epub 2023 Nov 15 [PubMed PMID: 38026611]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMagomedov MM, Borisova OY, Bakharev AV, Lapchenko AA, Magomedova NM, Gadua NT. [The multidisciplinary approach to the diagnostics and surgical treatment of the lacrimal passages]. Vestnik otorinolaringologii. 2018:83(3):88-93. doi: 10.17116/otorino201883388. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29953065]

Katowitz JA, Welsh MG. Timing of initial probing and irrigation in congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Ophthalmology. 1987 Jun:94(6):698-705 [PubMed PMID: 3627719]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceŚwierczyńska M, Tobiczyk E, Rodak P, Barchanowska D, Filipek E. Success rates of probing for congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction at various ages. BMC ophthalmology. 2020 Oct 8:20(1):403. doi: 10.1186/s12886-020-01658-9. Epub 2020 Oct 8 [PubMed PMID: 33032542]

Goel R, Sagar C, Gupta SN, Shah S, Agarwal A, Golhait P, Kumar S, Akash R. Outcome of transcanalicular laser dacryocystorhinostomy with endonasal augmentation in acute versus post-acute dacryocystitis. Eye (London, England). 2023 Apr:37(6):1225-1230. doi: 10.1038/s41433-022-02104-4. Epub 2022 May 19 [PubMed PMID: 35590102]

Goel R, Ojha S, Gaonker T, Shah S, Meher R, Arya D, Khanam S, Kumar S. Outcomes of 8 × 8 mm osteotomy in powered external dacryocystorhinostomy. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2023 Jun:71(6):2569-2574. doi: 10.4103/IJO.IJO_3328_22. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37322681]

Aboauf H, Alawaz RA. Success Rate of External Dacryocystorhinostomy With and Without Stent. Cureus. 2024 Jul:16(7):e63683. doi: 10.7759/cureus.63683. Epub 2024 Jul 2 [PubMed PMID: 39092337]