Introduction

The diaphragm begins to develop between the fourth and twelfth weeks of embryogenesis. During this period, the central tendon is formed from the anterior septum transversum, which then merges with the pleuroperitoneal folds on the sides and the dorsal mesentery of the esophagus in the center, creating the initial structure of the diaphragm. Additionally, the muscular portions of the diaphragm arise from the peripheral cervical somites at levels C3 to C5.

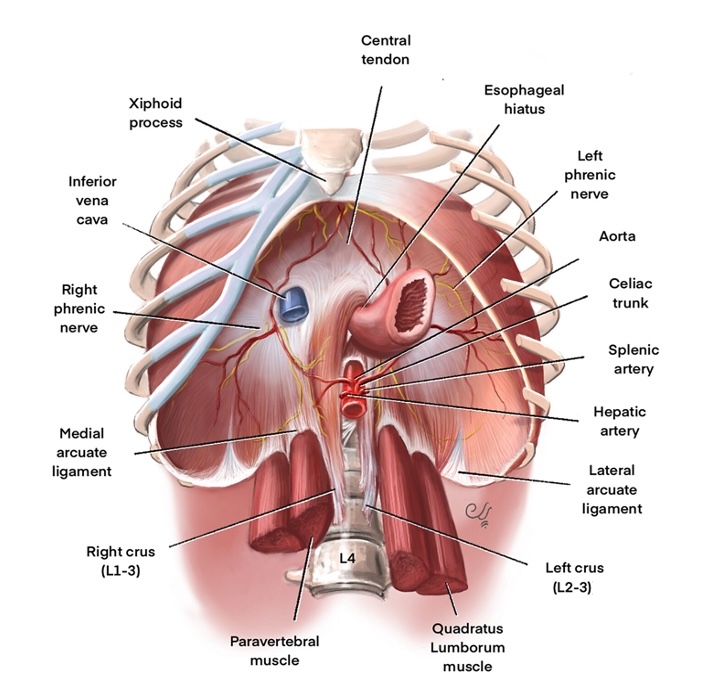

Upon its formation, the diaphragm is a dome-shaped structure measuring approximately 2 to 4 mm in thickness and is located at the lower boundary of the thoracic cavity. The central tendon, positioned beneath the heart, is fused with the parietal pericardium. At the same time, the surrounding muscle fibers attach to the sternal xiphoid process, the lower ribs, and the upper lumbar vertebrae. The crura, which anchors the diaphragm to the lumbar vertebrae, consists of the right crus attaching to vertebrae L1 to L3 and the left crus attaching to L2 to L3 (see Image. Normal Diaphragm Anatomy).[1]

The diaphragm is vital in the inspiratory phase of respiration and acts as a barrier between the thoracic and abdominal cavities. The left and right phrenic nerves provide the motor function to each hemidiaphragm, respectively, and impaired development or injury to this nerve can lead to diaphragmatic paralysis and diminished lung expansion. Diaphragmatic eventration is the abnormal elevation of a portion or entire hemidiaphragm due to a lack of muscle or nerve function while maintaining anatomical attachments. The abnormality can be congenital or acquired, thus presenting in pediatric and adult populations.

In both congenital and acquired eventration, a portion of the diaphragm is weakened and thin, causing reduced function. Patients may be asymptomatic or present with respiratory symptoms depending on the severity. Diagnosis is confirmed by radiographic imaging, and treatment usually consists of supportive care and, in some cases, surgical plication.[2][3][4]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Congenital eventrations are caused by abnormal diaphragm muscle development and can occur anteriorly, posterolaterally, and medially. Embryologically, there is a defect in the migration of myoblasts to the septum transversum, causing partial or total replacement of the diaphragm muscle with fibroelastic tissue. This creates a thin and weakened hemidiaphragm, resulting in a cephalic displacement on the affected side. Eventration can also occur in association with other congenital conditions and infections. These conditions include spondylocostal dysostosis, Kabuki syndrome, Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, Poland syndrome, chromosomal defects, pulmonary hypoplasia, spinal muscular atrophy, malrotation, and congenital heart disease. Mitochondrial respiratory chain disorder has been linked to diaphragmatic dysfunction in the neonatal period. Infectious associations include fetal rubella and cytomegalovirus infections.[5][6][7]

Acquired cases are more common and are due to etiologies that result in phrenic nerve injury and muscle atrophy. Injury may be due to blunt or penetrating trauma, birth trauma, or thoracic surgery. Phrenic nerve dysfunction or damage may also occur as a complication of other illnesses, including multiple sclerosis, Guillain-Barre syndrome, nerve compression, radiation therapy, and connective tissue diseases. Paralysis or phrenic nerve damage can lead to muscle atrophy and thinning of the diaphragm with cephalic displacement.[2][8] Eventrations, congenital and acquired, of the diaphragm are further divided on an anatomical basis as complete, partial, or bilateral.

Epidemiology

Due to the rarity of diaphragmatic eventration, there is limited data on the incidence and prevalence of this condition. A limited number of case reports have suggested the incidence is as low as less than 0.05%, with a predominance in men, most commonly affecting the left hemidiaphragm. Others have suggested the incidence to be 1 in 10,000 live births. The incidence is likely higher than reported as most patients are asymptomatic, and many remain undiagnosed.[6][9][10]

Pathophysiology

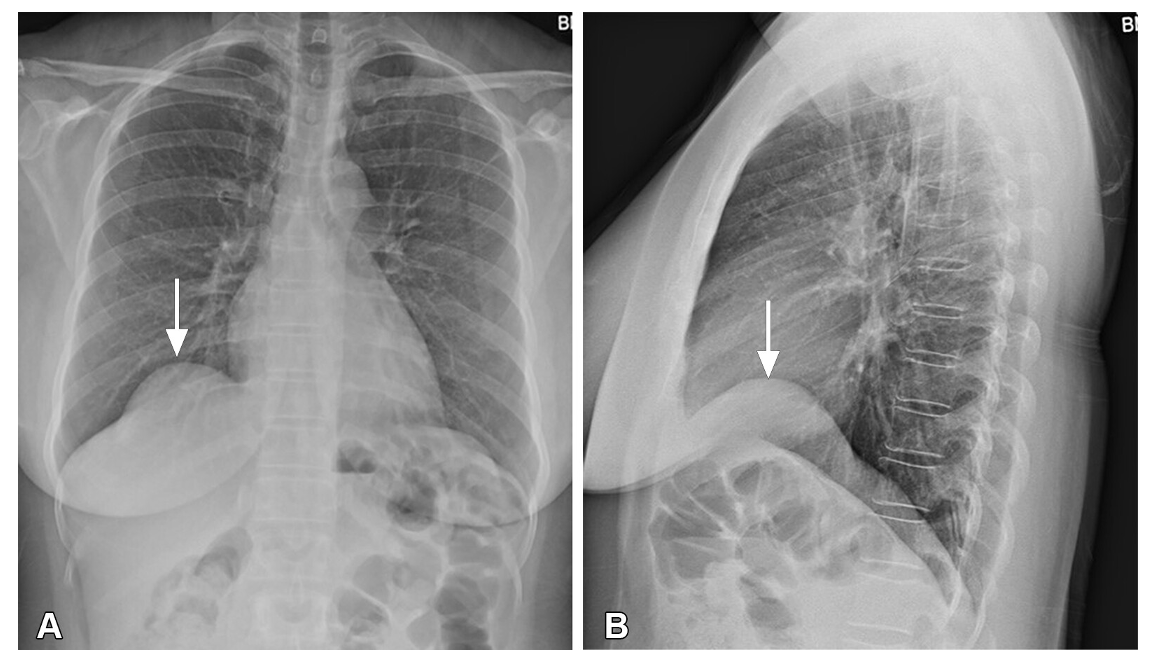

Diaphragmatic eventration refers to a localized elevation or bulging of 1 side of the diaphragm (hemidiaphragm) without any break in the continuity of the diaphragm. This condition may feature a distinct transition to the elevated area, sometimes resembling a mushroom shape (see Image. Diaphragm Eventration).[1] Neurogenic muscular aplasia of the diaphragm is the term used to describe stretched-out and aponeurotic scattered muscle fibers in a congenital diaphragm eventration. However, these changes are lacking in acquired form.[11]

History and Physical

History

Patients with eventration of the diaphragm have variable presentations. Most patients are asymptomatic, and the condition is discovered incidentally on chest x-rays; however, some may present with significant respiratory distress or gastrointestinal symptoms. Bilateral congenital diaphragmatic eventration in the neonate may present with acute respiratory failure and cyanosis. Respiratory symptoms in adult and pediatric cases may include dyspnea on exertion, orthopnea, tachypnea, and shallow breathing.

In adults, recurrent respiratory infections, lung atelectasis, or chronic productive cough may cause initial presentation. Adults may also complain of chest pain, which may be caused by arrhythmias or palpitations. Gastrointestinal symptoms in the adult population may worsen with increased intraabdominal pressure (eg, exercise, pregnancy, ascites, infection, fluid sequestration) and present with dyspepsia, dysphagia, gastroesophageal reflux, and epigastric pain.

In infants, respiratory symptoms are largely attributed to shifting the mediastinal structures to the contralateral side. Gastrointestinal involvement is common and may manifest as vomiting, bloating, constipation, poor weight gain, and poor oral intake. In severe cases, gastric volvulus may be present. All patients should be assessed for a history of trauma and other causes of respiratory distress.[2][11]

Physical Examination

The physical examination findings are variable and often nonspecific. Below is a list of physical findings that may be found in adults and pediatrics (shared), acquired (adult) cases, and congenital (pediatric) cases.

- Shared findings in adults and infants

- General:

- Tachypnea

- Central cyanosis if hypoxia is present (rare in unilateral cases)

- Lungs/thorax:

- Accessory muscle use

- Paradoxical movement of the chest wall during inspiration (on the affected side)

- Decreased tactile fremitus and dullness to percussion on the affected side

- Decreased breath sounds (unilateral or bilateral involvement)

- Gastrointestinal:

- Abdominal pain with palpation (usually epigastric or periumbilical areas)

- Bowel sounds within the thoracic cavity

- General:

- Congenital (infants)

- Lungs/thorax:

- Apparent signs of blunt or penetrating thoracic trauma

- Gastrointestinal:

- Scaphoid abdomen

- Severe epigastric pain related to gastric volvulus

- Musculoskeletal/neurological:

- Findings of Erb palsy (C5 and C6 injury) in those with birth trauma

- Clavicular fracture

- Arm is adducted and internally rotated

- Forearm is extended and pronated

- Findings of Erb palsy (C5 and C6 injury) in those with birth trauma

- Lungs/thorax:

- Acquired (adults)

- Lungs/thorax:

- Apparent signs of blunt or penetrating thoracic trauma

- Cardiovascular:

- Chest wall pain

- Tachycardia or arrhythmia

- Gastrointestinal:

- Abdominal pain due to causes of increased intraabdominal pressure

- Ascites

- Infection

- Fluid sequestration (third-spacing)

- Pregnancy

- Abdominal pain due to causes of increased intraabdominal pressure

- Lungs/thorax:

Evaluation

Acquired Diaphragm Eventration

Most patients with diaphragmatic eventration are asymptomatic. They are often unaware of their condition, and the diagnosis is typically an incidental finding on chest imaging. After a thorough history and physical examination, patients who are symptomatic should undergo chest imaging; radiographic findings on chest x-rays confirm the diagnosis of diaphragmatic eventration.

Chest x-ray imaging should include both posterior-anterior and lateral views. X-ray images will show an elevation of the affected portion of the hemidiaphragm and normal cardiomediastinal contours. Chest computed tomography (CT) may be done if the diagnosis is unclear or intrathoracic or intraabdominal abnormalities are suspected. A chest CT will show elevation of the affected portion of the hemidiaphragm and a sharp edge of the eventration. Diaphragmatic eventration can be differentiated from hernia due to the normal attachment sites of the diaphragm.[10][12]

Further evaluation is often reserved for assessing lung volumes and diaphragm function. These tests include pulmonary function testing (PFT), maximum inspiratory pressure (MIP), maximum expiratory pressure (MEP), fluoroscopic sniff testing, and ultrasonography. Laboratory testing may be necessary if there is suspicion of associated congenital diseases or infectious etiologies.

PFTs show a restrictive pattern with reduced forced vital capacity and forced expiratory volume in 1 second. This restrictive pattern is more commonly seen when eventration is bilateral. This has improved with diaphragm plication, which is further discussed in the next section.[12] The MIP and MEP measure the pressure generated during maximal inspiratory or expiratory effort and indicate the respiratory muscles' strength. As the diaphragm plays a role in the inspiratory phase, the MIP is reduced in patients with diaphragm eventration; the MEP is generally expected.[13]

Fluoroscopic sniff testing is used to examine diaphragm function under continuous fluoroscopy. The patient is asked to take hard and fast inspirations (sniffs) and assess the direction and motion of each hemidiaphragm. In diaphragm eventration, only a portion of the hemidiaphragm may show abnormal movement. Sniff testing may aid in distinguishing diaphragm paralysis from eventration, as paralysis may have paradoxical motion during sniffing. This is of limited value as diaphragm eventration and paralysis are treated with plication when conservative measures fail. In infants, the sniff test may be difficult to obtain. Ultrasonography of the diaphragm is often used in place of fluoroscopy to evaluate diaphragm function due to its lack of exposure to radiation to patients.[12][14]

Congenital Diaphragm Eventration

Diagnosis can be made prenatally with a high-resolution fetal ultrasound, CT, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Prenatally, diaphragm eventration is challenging to differentiate from congenital diaphragmatic hernia as the lung appears hypoplastic, and the fetal stomach or liver is visualized in the same transverse plane as the heart. Postnatally, eventration is suspected when a portion of the diaphragm is elevated on chest radiography when evaluating for respiratory distress. Confirmatory testing for diaphragm eventration includes fluoroscopy, dynamic MRI, or ultrasound to assess diaphragm function. Further evaluation should be tailored to the patient's clinical history and physical findings to determine the underlying etiology (eg, infections, malignancy, developmental and degenerative diseases).

Treatment / Management

Managing diaphragm eventration mostly depends on the disease’s etiology and severity. In asymptomatic or mild cases, supportive care is recommended. In cases of hypoxemia, oxygen supplementation should be provided to maintain appropriate oxygen saturation. When supplemental oxygen via nasal cannula is inadequate, patients may require nasal continuous positive airway pressure. As infants commonly present with gastrointestinal symptoms and failure to thrive, nutritional support should be optimized. Infants in significant respiratory distress may require gavage feeding or parenteral nutrition to maximize calorie intake, fluid intake, and electrolyte replenishment to meet metabolic demands. Conservative management may also include physical therapy and pulmonary rehabilitation.[10][11]

Surgical plication may be indicated in severe cases requiring mechanical ventilation or when patients fail to respond to medical management. Diaphragmatic plication is a known surgical treatment for eventration. The procedure involves creating pleats with U-stitches in the weakened hemidiaphragm and anchoring down. This results in a flattened and lowered hemidiaphragm, allowing for increased intrathoracic volume and lung expansion. Diaphragm plication can be done via open thoracotomy, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery, laparoscopic, or robotic-assisted surgery. After the surgery, a thoracostomy tube is placed for pleural drainage until the output is less than 200 mL/day. Notably, surgical plication does not improve the function of the hemidiaphragm.[12][15][16]

The indications for surgical plication are outlined below:

- Respiratory distress unresponsive to conservative treatment

- Dyspnea that is not due to another process (ie, heart failure or primary lung diseases)

- Infants with inadequate nutritional intake or failure to thrive

- Life-threatening or recurrent pneumonia

- Inability to be removed from mechanical ventilation

Patients should be monitored postoperatively, and the frequency of follow-up is variable depending on symptoms or complications. Follow-up tests may include posterior-anterior/lateral chest x-rays and PFTs. The St George Respiratory Questionnaire can monitor a patient’s quality of life, activity level, and psychosocial impact.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses to consider in cases of possible diaphragm eventration include:

- Diaphragmatic paralysis

- Difficult to distinguish from eventration

- Paralysis will involve the entire hemidiaphragm

- Eventration may involve a smaller portion or the whole hemidiaphragm

- Phrenic nerve palsy

- Diaphragmatic hernia

- Lung consolidation

- Subpulmonic pleural effusion

- Pleural mass

- Traction injury

- Iatrogenic injury during thoracic surgery

- Ascites

- Hepatic or splenic enlargement

Prognosis

The prognosis is generally good and may depend on the severity and etiology of the event. Most patients are asymptomatic and may not need any intervention. Those with extensive eventration may develop severe respiratory distress requiring mechanical ventilation. Diaphragm plication has significantly improved symptoms and quality of life in patients with extensive eventration. The procedure has also improved the forced expiratory volume in the first second and forced vital capacity by up to 30% on follow-up PFTs.[16][17]

Complications

Complications of diaphragm eventration include:

- Acute or chronic respiratory failure

- Pneumonitis

- Nutritional deficiency

- Failure to thrive

- Cardiac arrhythmias are possible due to acute mediastinal shifts

- Complications of surgical correction

- Pneumonia

- Deep venous thrombosis

- Pleural effusions

- Cardiac events

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Postoperative care occurs in the intensive care unit, especially in those requiring postoperative mechanical ventilation. This care includes but is not limited to:

- A trial of extubation

- This is critical as there is a change in thoracic and abdominal compliance with surgical incision and reduction of contents into the abdominal cavity.

- Monitoring intraabdominal pressure

- Increased pressures can indicate abdominal compartment syndrome, which is a surgical emergency.

- Incentive spirometry, pulmonary toilet, and adequate pain control

- An ineffective cough because of pain may promote the retention of secretions and atelectasis, leading to pneumonia and other issues.

Consultations

The following consultations may be obtained in cases of diaphragm eventration:

- Adult or pediatric pulmonologist

- Thoracic surgeon

- Intensivist

- Pulmonary rehabilitation

- Physical therapist

Deterrence and Patient Education

Eventration of the diaphragm is often an incidental finding, and most patients are asymptomatic without extensive management. Patients and parents of children with confirmed eventration of the diaphragm should be educated on recognizing symptoms and when to seek medical treatment. Pulmonary rehabilitation may also be beneficial in teaching patients about diaphragm eventration and breathing exercises.

Pearls and Other Issues

Clinical pearls for diaphragm enventration offer valuable insights and practical tips that enhance diagnostic accuracy and treatment efficacy. Key takeaways and best practices for managing diaphragm enventration in clinical settings include the following:

- Diaphragm eventration refers to the elevation of a portion of the diaphragm.

- The etiology is congenital or acquired.

- Congenital: Due to abnormal migration of myoblasts during development

- Acquired: Due to phrenic nerve injury (usually trauma or thoracic surgery)

- Both lead to thin, weakened diaphragm in affected regions

- Acquired causes are more common than congenital.

- Most patients are asymptomatic, and diagnosis is usually incidental.

- Patients who are symptomatic may have respiratory distress, poor oral intake, and gastrointestinal symptoms.

- Diagnosis is confirmed with radiographic imaging (chest radiograph, CT, ultrasonography, fluoroscopic sniff testing).

- Asymptomatic and mild cases are managed conservatively.

- Severe cases are treated with surgical plication of the diaphragm.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Enhancing patient-centered care, outcomes, patient safety, and team performance in managing diaphragm eventration requires a comprehensive strategy involving various healthcare professionals. Physicians must possess advanced diagnostic skills to accurately identify diaphragm eventration on imaging. They should also be proficient in surgical techniques for diaphragm plication if needed. Advanced clinicians, including nurse practitioners and physician assistants, play a crucial role in preoperative and postoperative care, ensuring thorough patient assessments and providing education on the condition and recovery process. Nurses are integral in monitoring patient vitals, managing pain, and assisting in respiratory therapy, while pharmacists contribute by optimizing medication regimens to support respiratory function and manage postoperative pain.

Effective interprofessional communication and care coordination are essential to achieving optimal outcomes. Regular interdisciplinary team meetings allow for exchanging crucial patient information and developing coordinated care plans. Physicians, advanced clinicians, and nurses must communicate clearly about patient status, surgical plans, and recovery progress. Collaboration with respiratory therapists ensures patients receive appropriate pulmonary rehabilitation, enhancing lung function and overall recovery. Additionally, involving social workers and case managers can help address socioeconomic factors that may impact patient care and recovery. This collaborative approach ensures that all aspects of the patient’s health are considered, leading to improved patient safety, better outcomes, reduced medical errors, and enhanced team performance in managing diaphragm eventration.[18]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Keyes S, Spouge RJ, Kennedy P, Rai S, Abdellatif W, Sugrue G, Barrett SA, Khosa F, Nicolaou S, Murray N. Approach to Acute Traumatic and Nontraumatic Diaphragmatic Abnormalities. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2024 Jun:44(6):e230110. doi: 10.1148/rg.230110. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38781091]

Wayne ER, Campbell JB, Burrington JD, Davis WS. Eventration of the diaphragm. Journal of pediatric surgery. 1974 Oct:9(5):643-51 [PubMed PMID: 4424891]

Oliver KA, Ashurst JV. Anatomy, Thorax, Phrenic Nerves. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30020697]

Mandoorah S, Mead T. Phrenic Nerve Injury. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29489218]

Kulkarni ML, Sneharoopa B, Vani HN, Nawaz S, Kannan B, Kulkarni PM. Eventration of the diaphragm and associations. Indian journal of pediatrics. 2007 Feb:74(2):202-5 [PubMed PMID: 17337837]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGuzman JPS, Delos Santos NC, Baltazar EA, Baquir ATD. Congenital unilateral diaphragmatic eventration in an adult: A rare case presentation. International journal of surgery case reports. 2017:35():63-67. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2017.04.010. Epub 2017 Apr 18 [PubMed PMID: 28448861]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGupta S, Wyllie J, Wright C, Turnbull DM, Taylor RW. Mitochondrial respiratory chain defects and developmental diaphragmatic dysfunction in the neonatal period. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstetricians. 2006 Sep:19(9):587-9 [PubMed PMID: 16966130]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTripp HF, Bolton JW. Phrenic nerve injury following cardiac surgery: a review. Journal of cardiac surgery. 1998 May:13(3):218-23 [PubMed PMID: 10193993]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAli Shah SZ, Khan SA, Bilal A, Ahmad M, Muhammad G, Khan K, Khan MA. Eventration of diaphragm in adults: eleven years experience. Journal of Ayub Medical College, Abbottabad : JAMC. 2014 Oct-Dec:26(4):459-62 [PubMed PMID: 25672164]

Makwana K, Pendse M. Complete eventration of right hemidiaphragm: A rare presentation. Journal of family medicine and primary care. 2017 Oct-Dec:6(4):870-872. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_283_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29564282]

Thomas TV. Congenital eventration of the diaphragm. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 1970 Aug:10(2):180-92 [PubMed PMID: 4913762]

Nason LK, Walker CM, McNeeley MF, Burivong W, Fligner CL, Godwin JD. Imaging of the diaphragm: anatomy and function. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2012 Mar-Apr:32(2):E51-70. doi: 10.1148/rg.322115127. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22411950]

Zoumot Z, Jordan S, Hopkinson NS, Polkey MI. Twitch transdiaphragmatic pressure morphology can distinguish diaphragm paralysis from a diaphragm defect. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2013 Jul 15:188(2):e3. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201207-1185IM. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23855705]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVerhey PT, Gosselin MV, Primack SL, Kraemer AC. Differentiating diaphragmatic paralysis and eventration. Academic radiology. 2007 Apr:14(4):420-5 [PubMed PMID: 17368210]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceVisouli AN, Mpakas A, Zarogoulidis P, Machairiotis N, Stylianaki A, Katsikogiannis N, Tsakiridis K, Courcoutsakis N, Zarogoulidis K. Video assisted thoracoscopic plication of the left hemidiaphragm in symptomatic eventration in adulthood. Journal of thoracic disease. 2012 Nov:4 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):6-16. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2012.s001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23304437]

Groth SS, Andrade RS. Diaphragm plication for eventration or paralysis: a review of the literature. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2010 Jun:89(6):S2146-50. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.03.021. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20493999]

Higgs SM, Hussain A, Jackson M, Donnelly RJ, Berrisford RG. Long term results of diaphragmatic plication for unilateral diaphragm paralysis. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2002 Feb:21(2):294-7 [PubMed PMID: 11825738]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMorey JC, Simon R, Jay GD, Wears RL, Salisbury M, Dukes KA, Berns SD. Error reduction and performance improvement in the emergency department through formal teamwork training: evaluation results of the MedTeams project. Health services research. 2002 Dec:37(6):1553-81 [PubMed PMID: 12546286]