Introduction

Esophageal ulcers are breaks in the esophageal mucosa that can form at any point along the esophagus. Exposure to irritants causes inflammation of the esophageal mucosa, leading to erosion and the formation of open sores. If left untreated, these mucosal wounds can lead to complications, such as bleeding, stricture formation, and perforation. With treatment, esophageal ulcers can heal within a few weeks to months but can recur if the underlying etiology is not adequately managed.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Esophageal ulcers have various etiologies, ranging from common causes like gastroesophageal reflux and medication-induced inflammation to rare infections and autoimmune conditions. Management depends on the underlying cause.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

The most common cause of esophageal ulcers is gastroesophageal reflux disease. Weakening or inappropriate relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter exposes the esophageal mucosa to acid when gastric content refluxes into the esophagus. Repeated exposure causes mucosal damage and irritation that can erode the protective mechanisms of the esophagus, thus leading to ulcer formation.

Medications

The second most common cause is drug-induced mucosal damage. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and antibiotics, especially doxycycline, are common culprits. Still, virtually any medication class can lead to ulcer formation, primarily due to these drugs' direct irritant effect on the esophageal mucosa. Other drugs that have been implicated include bisphosphonates, certain supplements (eg, iron, potassium, L-arginine, and caffeine), chemotherapeutic agents, immune checkpoint inhibitors, anticoagulants (eg, dabigatran and rivaroxaban), antiplatelets, antiarrhythmics, and antihypertensives.

Infections

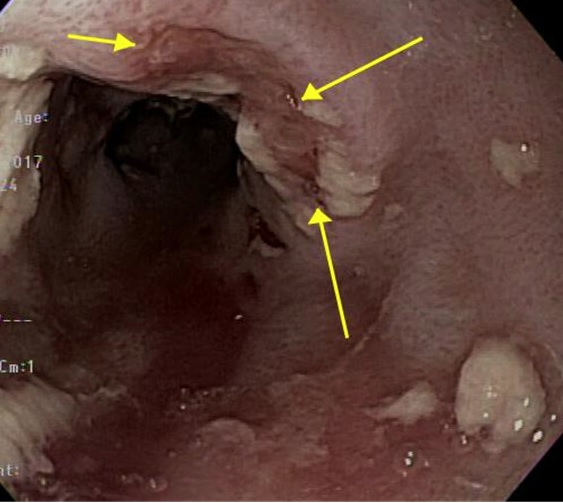

Infections from Candida, herpes simplex virus (HSV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) have been reported to cause esophageal ulcers.[1] Disseminated fungal infections such as histoplasmosis can also lead to esophageal ulcers (see Image. Esophageal Histoplasmosis). These infections are often seen in patients with immune deficiencies, such as transplant recipients and people with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. However, immunocompetent patients may also be affected. Rare causes of infectious esophageal ulcers include tuberculosis, COVID-19, and M-pox, which have only been seen in case reports.

Caustic Ingestion and Foreign Body Retention

Irritants such as cigarette smoke, alcohol, alkaline solutions like ammonia and sodium hydroxide, acidic foods, and caffeinated beverages cause ulcers through direct irritation upon contact.[2] Prolonged food impaction or thermal injury from ingesting hot foods may also lead to the development of ulcers through similar mechanisms.

Autoimmune, Inflammatory, and Genetic Conditions

Autoimmune and inflammatory diseases may also cause esophageal ulcers and should be included in the differential diagnosis. Crohn disease rarely involves the esophagus but can manifest as superficial ulcers, which most commonly arise in the middle-to-lower esophagus. This presentation may appear similar to CMV or HSV ulceration and is often challenging to diagnose.[3][4] Behçet disease is an inflammatory, autoimmune vasculitis that can present as esophageal ulcers in the middle-to-lower third of the esophagus. Dermatologic conditions such as systemic sclerosis, dermatomyositis, pemphigus, pemphigoid, lichen planus, and epidermolysis bullosa may also involve the esophageal mucosa. Genetic conditions like chronic granulomatous disease, an inherited disorder due to mutations in the reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase complex, usually affect the gastrointestinal tract and can present as inflammatory bowel disease. However, a small proportion of patients may present with esophageal ulcers.

Malignancy

Malignant causes of ulcers include squamous cell cancer (SCC), which usually forms in the upper and middle parts of the esophagus, and adenocarcinoma, which typically forms in the lower third of the esophagus. Risk factors of SCC include tobacco use, heavy alcohol consumption, caustic ingestion, achalasia, and, in rare cases, Fanconi anemia. Risk factors for developing esophageal adenocarcinoma include gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), Barrett esophagus, obesity, and smoking. Other malignancies, including lymphoma, sarcoma, and metastasis, are less common.[5][6]

Iatrogenic, Postsurgical, and Radiation-Induced Injury

Radiation to the thoracic area for breast, lung, esophageal, or lymphomatous cancers can cause esophageal ulcers in severe cases of radiation esophagitis. Ulcers may form as a postprocedural complication, for example, from trauma induced by nasogastric tube placement or endoscopic ultrasound, ischemia after esophageal variceal banding, and thermal injury following pulmonary vein isolation catheter ablation for treatment of atrial fibrillation. Postsurgical marginal ulcers can occur due to microvascular injury during surgery and postsurgical inflammation, resulting in tissue ischemia and, ultimately, ulcer formation. Contributing factors that increase the risk of developing marginal ulcers include tobacco smoking, NSAID use, and Heliobacter pylori infection.

Epidemiology

Ulcers Due to Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

GERD continues to be the most common cause of esophageal ulcers, accounting for 57% to 79% of all ulcers.[7] The prevalence of GERD in North America ranges between 18% and 27% and appears to affect men and women equally. In South America and the Middle East, women are more likely to report GERD symptoms than men. No clear association between ulcers and advanced age has been reported.[8]

Pill-Induced Ulcers

The second most common cause of esophageal ulcers is medication-induced irritation, which can account for up to 22% of these lesions. Doxycycline and NSAIDs are the most commonly reported causes of pill-induced esophageal ulcers in both adolescents and adults. Results from a single-center, retrospective analysis involving adolescents with esophageal ulcers in Taiwan found that doxycycline accounted for 56.3% of the ulcers, NSAIDs comprised 18.8%, other antibiotics caused 15.6%, and L-arginine was responsible for 3.1%.[9]

According to a single-center, retrospective study from Turkey, doxycycline-induced esophageal ulcers are just as common in adults, accounting for 52% of ulcers.[10] NSAID-related ulcers can account for up to 7% of ulcers, according to the results of a single-center, retrospective study in Israel. Population studies comparing incidence across different medication classes are lacking, and further investigation is needed.

Ulcers Related to Infection, Ingestion, and Iatrogenic Injury

Results from a single-center retrospective study based in Israel showed that Candida infections were the most common infectious cause of esophageal ulcers, accounting for 2% of ulcers. HSV, CMV, and HIV each accounted for 1%. Caustic ingestion and radiation each had an estimated 1% to 2% prevalence. Population studies are lacking, but sex and age do not appear to influence the occurrence of esophageal ulcers arising from these mechanisms.

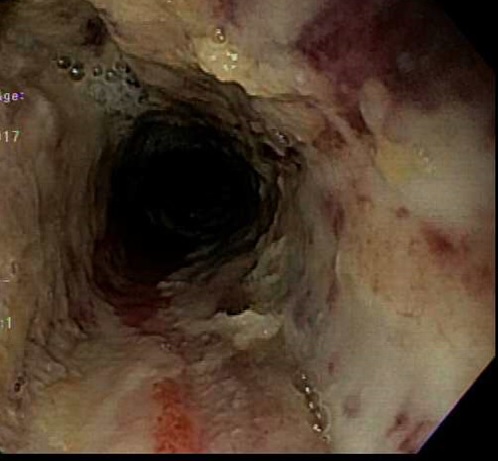

Postbanding ulcers occur in 4.6% to 5.5% of variceal band ligation cases (see Image. Postbanding Esophageal Ulcers). Risk factors associated with ulcer bleeding post banding include poor liver function, assessed by the model-end liver disease score, hepatocellular carcinoma, and total β-blocker dose.[11][12] Thermal injuries from atrial fibrillation ablations have been reported in up to 40% of patients after primary valvular incompetence.[13]

Autoimmune Ulcers

Upper gastrointestinal involvement in Crohn disease, which may span the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum, is prevalent in symptomatic adult patients at a rate of 0.5% to 4%.[14] Esophageal Crohn disease is rare, and a retrospective study from Mayo Clinic in North America found it in 0.2% of 12,367 patients. However, most patients with esophageal Crohn disease have extraesophageal involvement. The esophagus is involved in approximately 47% to 68% of pemphigus vulgaris cases, whereas only 4% to 11% of mucous membrane pemphigoid cases have associated esophageal findings. Esophageal involvement in lichen planus is seen in 26% to 50% of patients and disproportionately affects women.[15]

Chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) is typically identified in childhood before age 5. However, up to 15% of patients can remain undiagnosed until the second or third decade of life. CGD affects the gastrointestinal tract and can present as inflammatory bowel disease. Results from a retrospective study by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) from 1990 through 2010 showed that 4 out of 57 (7%) patients with CGD who underwent upper endoscopy had esophageal ulcers.[16] The association between Behcet disease and esophageal ulcers is rare and has been reported in a few case studies.[17][18][19]

Malignancy-Related Ulcers

The incidence of esophageal cancer has been increasing worldwide over the past few decades. According to the recent American Cancer Society data, esophageal cancer occurs predominantly in men. In 2024, the incidence of esophageal cancer in men was 17,690 compared to 4680 in women. Associated mortality was reported in 12,880 men and 3250 women.[20]

Although esophageal SCC is the most prevalent worldwide, the incidence of adenocarcinoma is on the rise. Adenocarcinoma is now the most prevalent esophageal cancer histology in the United States and Western Europe, notably affecting White men. The rise in the incidence of adenocarcinoma is currently unknown. Still, it may be related to obesity and GERD, as this histology is more commonly seen in the distal esophagus, with Barrett esophagus as the precursor lesion. (National Cancer Institute Esophageal Cancer Treatment)

Pathophysiology

Ulcers from Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Prolonged exposure to any caustic agent, including gastric acid, can lead to esophageal mucosal injury. Gastric acid is a combination of hydrochloric acid, lipase, and pepsin that functions to digest food and inactivate swallowed microorganisms. Gastric acid has a pH of less than 4.[21]

Normally, gastric acid is prevented from refluxing into the esophagus by an antireflux barrier. This barrier is comprised of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), the angle of His (also called the "esophagogastric angle"), the crural diaphragm, and the phrenoesophageal ligament.[22][23] Under normal circumstances, the LES resting pressure is 15 to 30 mm Hg greater than the intraabdominal pressure. This pressure gradient prevents refluxate from entering the lower portion of the esophagus. However, in patients with persistently low LES pressure, ie, less than 6 mm Hg, gastric pressure can easily overcome the LES-gastric gradient, allowing acid to reflux into the distal esophagus.

Decreased LES resting tone has been associated with severe esophagitis. Factors that lower LES pressure and tone include hormones such as cholecystokinin and progesterone (eg, during pregnancy), medications like nitrates and calcium channel blockers, high-fat meals, smoking, caffeine, and alcohol. Reflux can also occur at normal LES pressure during transient LES relaxations (tLESRs). Distention of the proximal stomach is the dominant stimulus for tLESRs, which account for up to 90% of reflux events in healthy individuals and patients with GERD but without hiatal hernias.[24][25]

The angle of His is the angle between the esophagus and the fundus of the stomach, acting as a flap valve that prevents reflux. Hiatal hernias disrupt this angle and the antireflux barrier. The severity of hiatal hernias is graded using the Hill classification based on the appearance of the gastroesophageal flap valve during endoscopy.[26] Once reflux occurs, 3 factors directly impact the exposure time between the esophageal mucosa and the caustic, irritating refluxate. First, ineffective or weak peristalsis increases acid exposure. Second, reduced salivary function can increase acid clearance time. Bicarbonate present in saliva is important in neutralizing and buffering acid, and growth factors, such as epidermal growth factor, contribute to mucosal repair and protection. Third, the presence of a hiatal hernia anatomically prevents esophageal emptying during swallowing.

Infection-Related Ulcers

Candida is part of the normal oral flora but becomes pathologic when fungal overgrowth occurs or when cell-mediated immunity is impaired in individuals with suppressed immunity. Chronic use of swallowed or inhaled steroids, recent antibiotic use, poorly controlled diabetes, and abnormal esophageal motility are risk factors for fungal overgrowth. HSV and CMV pathogenesis are similar. Both are deoxyribonucleic acid viruses that may be acquired through sexual and vertical transmission. Primary infection may cause fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy, and esophagitis. However, most individuals are asymptomatic, with the virus remaining latent for long periods. Reactivation due to immunodeficiency can lead to esophagitis and potential involvement of other organs.[27][28]

Ulcers Due to Ingestion of Caustic Agents and Pills

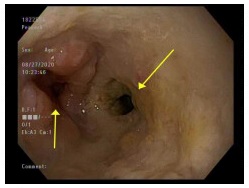

Ingestion of alkaline agents, such as ammonia and sodium hydroxide, causes a reaction with proteins and fats, leading to liquefactive necrosis. In contrast, acid-induced injury typically results in superficial coagulation necrosis, which thromboses underlying mucosal blood vessels and consolidates connective tissue, forming a protective eschar. Mucosal injury occurs within minutes of caustic ingestion (see Image. Caustic Ingestion on Endoscopy). In the first several days to a week, the mucosa will slough off, bacterial invasion occurs, and granulation tissue and collagen begin to form.

The risk of esophageal perforation is highest within the first 3 weeks when the esophageal tensile strength is at its lowest. After the 3rd week, the scar will begin to retract, and strictures may form over the next several months as the mucosa continues to heal.[29] Pill-induced esophageal ulceration results from local injury caused by pills in direct contact with the esophageal mucosa. Pills with an acidic pH more commonly irritate the mucosa, as they can destroy its cryoprotective barrier, leading to ulcer formation.[30][31]

Ulcers Related to Dermatologic and Autoimmune Diseases

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune dermatologic disease arising from antibodies targeting desmosomes, leading to a loss of cell-to-cell adhesion. The intraepithelial vesiculobullous lesions found on the skin and in the oropharynx are often Nikolsky sign-positive. In contrast, pemphigoid disorders are characterized by autoantibodies that target the basement membrane. The subepidermal bullae seen in mucous membrane pemphigoid are Nikolsky sign-negative. Both pemphigus and pemphigoid diseases are more likely to affect the proximal than the distal esophagus.

Esophageal lichen planus is an inflammatory condition. The exact pathophysiology of this condition is still unknown, but the underlying mechanism is believed to be a T-cell-mediated inflammatory reaction.[32] Crohn disease is multifactorial. One mechanism involves immune system dysregulation, particularly from T-cell hyperactivity and excessive production of inflammatory cytokines, including interleukins (IL)-12 and 23, and interferon γ, which promote mucosal inflammation.

Genetic mutations in FUT2 and Mut2 have also been implicated in Crohn disease. FUT2 encodes the fucosyltransferase enzyme, which is responsible for the secretion of ABO antigens. Mutations in this gene reduce the secretion of antigens, leading to altered interactions between bacteria and the mucosal barrier.

Immune cells such as cluster of differentiation (CD)8+ T cells, B cells, and CD14+ monocytes invade the intestinal mucosa and contribute to the pathogenesis of Crohn disease. CD4+ T cells promote plasma cell differentiation, and IL-21 secreted by CD4+ T cells converts naive B cells into mature B cells, which then secrete granzyme-B, a protease involved in cell apoptosis.[33]

Ulcers from Iatrogenic and Postsurgical Injuries

Pulmonary vein ablation for atrial fibrillation is a minimally invasive procedure that entails inserting a catheter through the femoral vein and advancing it toward the coronary sinus. The septum is then punctured, and the pulmonary vein is accessed. Radiofrequency or cryoablation is used to ablate the pulmonary vein. Temperatures can rise during ablation, causing thermal lesions in the anterior wall of the esophagus, which is adjacent to the left atrium. Ulceration, even perforation, can occur, depending on the extent of the injury.[34]

After esophageal banding for esophageal varices, a superficial ulcer forms at the ligation site due to tissue ischemia. Significant bleeding can occur from the newly formed ulcer if the esophageal bands slip off prematurely, as the varix has not yet adequately thrombosed. The pathophysiology of marginal ulcers at the postsurgical anastomosis is not fully understood, though several mechanisms have been proposed. Risk factors such as tobacco use, esophagogastric surgeries, and alcohol impair tissue perfusion, leading to tissue ischemia and inflammation, which ultimately cause ulcerations.[35]

Histopathology

Ulcers Due to Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Pill Esophagitis

Histologic findings in reflux esophagitis include basal cell hyperplasia, inflammation, dilated vascular channels in the papillae of the lamina propria, papillary elongation, and distended, pale squamous ("balloon") cells. Pill esophagitis may look similar on histopathological analysis, but key differences include intraepithelial eosinophil microabscesses, dilated intercellular spaces, and intraepithelial pustules. Pill residue is also an additional histologic clue that differentiates between pill and reflux esophagitis.[36]

Caustic Ingestion Ulcers

Corrosive esophagitis in the acute necrotic phase shows evidence of intracellular protein coagulation. Necrosis, hemorrhagic infiltration, and thrombosis of surrounding vessels may also be seen.[37]

Fungal Infection-Related Ulcers

Histopathological analysis of Candida esophagitis typically shows evidence of acute inflammation, neutrophilic abscesses, and edema in epithelial cells. Basal zone hyperplasia, parakeratosis, and hyperkeratosis are commonly observed. Yeast cells and pseudohyphae may be identified using Grocott methenamine silver stain. Histoplasma can be difficult to detect in chronic cases with calcifications and extensive fibrosis. However, Grocott or Gomori methenamine silver staining can reveal the organism in the central necrotic debris as small yeast forms.[38]

Viral Infection-Related Ulcers

Biopsies from a CMV ulcer bed typically demonstrate mucosal inflammation, tissue necrosis, vascular endothelial cell damage, and intranuclear and intracytoplasmic inclusions. The characteristic cytomegalic cells—large cells containing eosinophilic intranuclear and often basophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions—are commonly referred to as "owl's eye" and may be seen in mucosal biopsies stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Histology of HSV ulcers on hematoxylin and eosin stains shows Cowdry A inclusion bodies, which are large, red intranuclear inclusion bodies. Multinucleated giant cells with ground-glass nuclei are also present in the epithelial cells. Biopsies are ideally taken from the ulcer edges.[39]

Ulcers from Autoimmune and Dermatologic Conditions

In pemphigus, histopathology usually reveals acantholytic cells with a "tombstone" appearance in the basal layer and intraepithelial bullae. Immunofluorescence staining for autoantibodies against immunoglobulins (IG)G and A (IgA) and C3 complement demonstrates deposition in a net-like pattern. Diagnosis of esophageal pemphigoid is more challenging, as histologic features in the esophagus often do not show the same immunofluorescence staining as in skin tissue. Skin histology reveals subepithelial bullae and linear immunofluorescent staining of IgG along the basement membrane.

Histologic findings in lichen planus include a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate in the lamina propria, detachment of the squamous epithelium, epithelial apoptosis (Civatte bodies), hyperplasia, hypergranulosis, and surface orthokeratosis, also known as esophageal epidermoid metaplasia. Esophageal Crohn disease is rare, and biopsies may show noncaseating granulomas, although this feature is not always present. The most common histologic finding is lymphocytic infiltration in the lamina propria.[40]

Malignancy-Related Ulcers

The 2 histologic types accounting for most esophageal cancers are adenocarcinoma and SCC. Primary esophageal lymphoma and sarcoma are extremely rare but have been reported in the literature, accounting for less than 1% of primary esophageal tumors.

Radiation-Induced Ulcers

Apoptotic bodies are observed within the first 48 hours of radiation esophagitis. Within the first few weeks, mucosal glands degenerate or become distended with secretions, and submucosal endothelial swelling and capillary dilation are seen. Esophagitis and ulceration occur within a month. Radiation-related atypia of endothelial and stromal cells can mimic CMV, but this condition may be ruled out if the virus is not detected on immunostaining. Inflammation usually resolves within 3 to 4 weeks after the last fraction of radiation, but chronic changes can persist. Findings include submucosal thickening, edema, and mural fibrosis, which can lead to stricture formation.[41]

History and Physical

When taking a history, patients with esophageal ulcers may report a variety of symptoms, which may include heartburn, regurgitation of acid, noncardiac substernal chest pain, dysphagia, odynophagia, globus sensation, nausea, vomiting, and lack of appetite. In bleeding ulcers, signs of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) may be evident, including hematemesis, coffee ground emesis, and melena. In brisk UGIB, patients may also present with hematochezia, resulting in hemodynamic instability. The timing and onset of symptoms, aggravating factors such as trigger foods, and any remedies trialed to alleviate symptoms should be noted. Malignancy should be suspected in cases of rapid, unintentional weight loss.

Further history-taking should review comorbidities, recent surgeries or procedures, prior endoscopic evaluations, medications, and lifestyle practices. Opportunistic infections from CMV, Candida, or HSV should be suspected in patients with compromised immunity, especially bone marrow or solid organ transplant recipients and people living with HIV/AIDS. The clinician should ask when medications started and how long therapy has been. Patients with immune checkpoint inhibitors can develop CMV or HSV infections anytime during treatment.

A thorough social history should include questions about tobacco or alcohol use, diet, and caustic ingestion. Marginal ulcers should be considered in individuals who have had recent upper gastrointestinal surgeries and are actively smoking. When caustic ingestion is suspected, information regarding timing, type of substance, concentration, volume, and coingested substances is critical. If pill esophagitis is suspected, the clinician should inquire about how medications are administered. Dosages, frequency of administration, water intake during swallowing, recumbency after swallowing pills, and length of treatment should be included in the assessment.

Physical examination of the oropharynx may demonstrate oropharyngeal candidiasis in the form of thrush, which is comprised of patches of white overgrowth that may be scraped off. Patients may have abdominal tenderness with palpation, particularly in the epigastric region. Rectal examination may reveal signs of active or recent UGIB. Substernal crepitus or peritonitis may indicate esophageal perforation. The skin should be evaluated for rashes, blisters, bullae, or cutaneous ulcers, which may suggest an underlying autoimmune dermatologic condition.

Evaluation

The gold standard for diagnosing esophageal ulcers is upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, which provides both diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities. Other diagnostic modalities may be performed if clinically warranted.

Endoscopic Findings

GERD-induced esophageal ulcers usually occur at the squamocolumnar junction and are commonly seen in the lower esophagus with associated reflux esophagitis. Meanwhile, NSAID- and pill-induced esophageal ulcers appear as large, shallow ulcers in the midesophagus near the aortic arch surrounded by normal mucosa. Ulcers caused by immune checkpoint inhibitors appear shallow with reddish ulcer margins.[42]

CMV-related ulcers vary widely in appearance, number, and size and can appear similar to HSV-related ulcers. HSV ulcers usually occur in the middle-to-lower esophagus and appear as shallow, well-circumscribed ulcers with raised margins formed from precursor vesicles coalescing. Vesicles, bullae, or pseudomembranes may also be evident. The surrounding mucosa is usually intact.

CMV ulcers are usually deep, punched-out lesions that are linear or longitudinal, with an uneven base or yellow exudate. These lesions may also be serpiginous and are more often circumferential than HSV ulcers. Definitive diagnosis requires histopathological examination on biopsy. Coinfection can also occur.[43] Biopsies for CMV should be taken from the ulcer bed, while HSV biopsies should include the ulcer margins, with the highest diagnostic yield. Viral culture and polymerase chain reaction can also help diagnose infectious etiology.[44]

In pemphigus vulgaris, strictures, blisters, vesiculobullous lesions, and furrows can be seen on endoscopy. The mucosa may also easily slough off during endoscopy, as it is often Nikolsky sign-positive. In mucous membrane pemphigoid, endoscopic findings include esophageal webs, esophageal stenosis, and erosions. The hallmark of lichen planus is denudation and sloughing of the esophageal mucosa, which may be observed in all parts of the esophagus but has mostly been seen in the middle third. Trachealization and leukoplakia may also be found. Esophageal strictures and stenosis may be present, similar to other chronic inflammatory sequelae.

In esophageal Crohn disease, ulcers and erosions are surrounded by normal-appearing mucosa. Parts of the mucosa may exhibit cobblestoning. The middle and distal esophagus are most commonly involved. Ulcers secondary to Behcet disease are found in the middle-to-lower third of the esophagus and appear as small oval, discrete ulcers with erythematous margins. These lesions may also occur as longitudinal, elliptical ulcers with irregular borders.

Endoscopic findings in caustic injuries are scored using the Zargar classification as follows:

- Grade 0: Normal mucosa

- Grade I: Edema and erythema of the mucosa

- Grade IIA: Superficial ulcerations, erosions, blisters, friability, exudates, or hemorrhages

- Grade IIB: Circumferential ulcerations

- Grade IIIA: Focal areas of necrosis, seen as deep gray or brownish-black ulcers

- Grade IIIB: Extensive areas of necrosis

- Grade IV: Perforation [45]

Endoscopic findings in radiation esophagitis may include erythema, erosion, mucosal sloughing, ulceration, and hemorrhaging. Stricturing may also be present in chronic esophagitis.

Alternative Imaging Modalities

When endoscopy is not readily available, barium esophagograms or swallows can serve as valuable alternatives for initial evaluation. These imaging tests may be performed as single- or double-contrast swallows. The double-contrast technique provides more detailed mucosal information, making it the preferred method for evaluating esophagitis and ulcers.

Ulcers related to GERD are typically seen in the lower third of the esophagus on radiographs and appear as linear, stellate, or punctate lesions surrounded by mucosal edema, which presents as a radiolucent halo on barium swallow studies. HSV esophagitis appears as multiple small, circular, stellate, or punctate ulcers surrounded by edema. CMV ulcers can vary in number and appearance, often oval or diamond-shaped and can be several centimeters long, surrounded by mucosal edema.

Acute radiation esophagitis, typically 2 to 4 weeks after radiotherapy, shows granulations with ulcerations and reduced luminal expansion. Chronic radiation esophagitis, occurring 4 to 8 months after radiotherapy, is characterized by long segments of concentric and smooth structuring. Ingestion of caustic materials in the acute phase typically presents with ulcerations, and contrast extravasation from the esophageal lumen suggests perforation. Drug-induced esophagitis, most commonly from doxycycline or tetracycline, produces superficial ulcers in the upper-to-middle esophagus.[46]

Treatment / Management

Endoscopic hemostasis is the first-line treatment for patients with bleeding esophageal ulcers. Standard-of-care therapies include injection, mechanical clips, and thermal coagulation. Newer interventions for hemostasis include topical hemostatic powders and gels. Refractory bleeding may warrant interventional radiology and surgery consultations. The treatment of esophageal ulcers depends on the underlying etiology.

Ulcers from Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

North American guidelines from the American College of Gastroenterology and the American Gastroenterological Association provide similar recommendations. According to the 2022 guidelines, the treatment of GERD should include medical management with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), which should be taken 30 to 60 minutes before a meal. Weight loss should be recommended for patients with obesity or overweight. Lifestyle modifications, discussed below, are recommended for all individuals with GERD.

If daily PPI dosing is ineffective, the dose should be increased to twice daily. Once symptoms are controlled, experts recommend reducing the dose to the lowest effective level. PPIs are preferred over H2 blockers, although H2 blockers taken before bedtime may be effective for patients with nocturnal symptoms despite PPI therapy. In patients without esophagitis or Barrett esophagus, PPIs should be discontinued once symptoms resolve.

For patients with moderate to severe esophagitis (Los Angeles Grade C or D), maintenance PPI therapy is recommended indefinitely to ensure long-term healing. Sucralfate is not recommended except during pregnancy, and prokinetic agents should only be used if the patient has proven gastroparesis.[47] Fundoplication is an effective endoscopic option for select patients with confirmed GERD. When bariatric surgery is indicated, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is an effective antireflux intervention, while sleeve gastrectomy may worsen GERD.[48]

Infection-Related Ulcers

The treatment of infectious esophageal ulcers is determined based on the infecting organism. CMV infections in people with suppressed immunity are treated with ganciclovir for 14 to 21 days or longer, depending on the severity of the infection and clinical response. Valganciclovir is preferred for solid organ or hematopoietic cell transplant recipients. Dosing and treatment duration depend on the type of transplant, number of posttransplant days, and HIV status. Recurrence is common in these patients, and repeated treatments may be necessary due to ongoing immunosuppression. Foscarnet may be used off-label in cases of CMV esophagitis resistant to ganciclovir.[49]

HSV esophagitis is treated with acyclovir for 14 to 21 days in patients with immunodeficiency, while it is typically self-limiting in immunocompetent hosts. Esophageal candidiasis is most commonly treated with oral fluconazole for 14 to 21 days, which may also be administered intravenously for patients who cannot tolerate oral medications. Alternative therapies include itraconazole, voriconazole, posaconazole, and, in rare cases, amphotericin B for patients with unresponsive Candida esophagitis.[50]

Ulcers from Caustic Ingestions, Irritants, and Radiation

First and foremost, airway and hemodynamic stabilization are critical in managing caustic ingestion. All patients should be immediately evaluated for the need for intubation or tracheostomy. If intubation is required, fiberoptic laryngoscopy is recommended. Tracheostomy is advised in cases of upper airway edema.

Once airway management is addressed, patients should be put on nil-per-os (NPO or nothing by mouth) status. Early upper endoscopy is recommended within 24 to 48 hours of ingestion. This timeframe is crucial due to the increased risk of perforation beyond 48 hours from the decreased tensile strength of the esophageal wall. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography imaging should be considered in patients with suspected esophageal perforation.

Treatment may be stratified based on the Zargar endoscopic scoring of caustic injury. Patients with grades I to IIA injuries should be observed in the hospital for 24 to 48 hours. Their diet may be gradually advanced as tolerated. Individuals with grades IIB to IIIB injuries require closer monitoring. Depending on the severity, admission to the intensive care unit may be necessary.

Nasogastric tubes, placed endoscopically, provide a route for enteral feeding and serve as a stent to maintain lumen patency. Patients should remain on NPO status for at least 2 to 3 days. In more severe injuries, observation in the hospital for at least 1 week is recommended. H2 blockers or PPIs should be initiated to reduce gastric acid production and promote mucosal healing. In small randomized controlled trials, sucralfate has demonstrated the ability to decrease stricture formation by acting as a physical barrier between the corrosive agent ingested and the esophageal mucosa. However, evidence regarding the role of steroids in preventing esophageal strictures is conflicting.

Ulcers Due to Autoimmune Inflammatory Conditions

Treatment for pemphigus and pemphigoid diseases is similar and typically involves systemic steroids. If patients do not respond to steroids, immunotherapy options such as rituximab and cytotoxic agents (mycophenolate, azathioprine, or cyclophosphamide) are considered. In severe, progressive cases where steroids and immunotherapy fail, intravenous immunoglobulin or plasma exchange may be administered. Endoscopic dilation may be performed in patients with esophageal strictures due to pemphigus. However, this procedure is only recommended in cases of mucous membrane pemphigoid once the disease is adequately controlled with medical management, as patients are at a higher risk for esophageal perforation after dilation.[51][52]

Guidelines for the treatment of esophageal lichen planus have not been established. Swallowed corticosteroids, such as fluticasone and budesonide, have shown effectiveness. In severe cases, systemic steroids can induce remission, but they are not sufficient for long-term maintenance. However, other systemic immunosuppressive agents, including adalimumab, rituximab, tacrolimus, mycophenolate, azathioprine, cyclosporine, hydroxychloroquine, and cyclophosphamide, may be used for maintenance therapy.

Management of refractory cases should involve an interprofessional approach, with collaboration between at least a gastroenterologist and a dermatologist. Due to the risk of progression to SCC, surveillance with endoscopy every 1 to 2 years is recommended. No standard treatment approach has been proposed for esophageal Crohn disease due to its rarity and the lack of completed clinical trials. PPIs are used for symptomatic relief, though their effectiveness in promoting endoscopic healing remains unproven.

A few case reports suggest that topical therapies, such as swallowed mesalamine and budesonide, may be effective. Systemic steroids, thiopurines, and biologics are typically used in cases where patients do not respond to topical treatments. For complicated cases involving esophageal strictures, fistulas, or disease refractory to medical therapy, surgical resection, endoscopic dilation, and percutaneous gastrostomy for temporary enteral nutrition may be necessary.

Postsurgical Marginal Ulcers

Similar to GERD treatment, marginal ulcers are treated with acid-reducing medications, such as a PPI or an H2 blocker. Sucralfate may also be used. Lifestyle modifications, such as weight loss, abstinence from using tobacco products and alcohol, and avoidance of NSAIDs are recommended. Ulcers unresponsive to medical management or lifestyle modifications may warrant endoscopic suturing, stenting, or surgery, which requires an interprofessional discussion.

Iatrogenically Induced Ulcers

Thermal injuries from atrial fibrillation ablation are treated with 2 to 4 weeks of PPI. A follow-up endoscopy should be performed to evaluate for healing. No treatment guidelines for thermal injuries have been established, but antibiotics and corticosteroids have been used to reduce airway edema.

Nonbleeding postbanding ulcers are self-limited and heal with time. Postbanding ulcer bleeds are treated with a combination of vasoactive agents, PPIs, and endoscopic band ligation or sclerotherapy. For bleeding refractory to medical and endoscopic therapy, rescue therapies, such as an esophageal stent, Sengstaken-Blakemore tube, and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt placement, are considerations.

Malignancy-Related Ulcers

Treatment of esophageal cancer includes surgical resection, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and radiation. In cases of metastasis, the management is guided by the underlying primary cancer.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of esophageal ulcers is based on presenting symptoms of chest pain, dysphagia, odynophagia, bleeding, nausea, and vomiting and can be broad. The history, physical examination, and initial laboratory and imaging findings can help distinguish these conditions and make the correct diagnosis.

Gastrointestinal Conditions

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- Peptic ulcer disease

- Acute cholecystitis and biliary colic

- Pancreatitis

- Gastrointestinal foreign bodies

- Esophageal motility disorders such as achalasia and spasms

- Esophageal stricture

- Gastric outlet obstruction

- Mallory-Weiss tear

- Esophageal perforation

- Esophageal fistula (see Image. Esophageal Fistula)

- Esophageal and gastric malignancy

Extraintestinal Conditions

- Bronchoenteric fistula

- Acute coronary syndrome

- Mediastinitis

- Pleuritis and pneumonia

- Pericarditis

- Congestive heart failure

- Pulmonary embolism

- Mediastinal malignancy

- Thyroid nodules

- Aortic dissection

Careful clinical evaluation and diagnostic testing are key to narrowing down the list of possibilities and implementing the appropriate treatment plan. Coexisting conditions must also be considered, especially in the presence of systemic disease manifestations.

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients with esophageal ulcers depends on their immune status, comorbidity, age, and cause. The prognosis is generally good for individuals who comply with treatment.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease-Related Ulcers

The prognosis of GERD depends on several factors, including the severity of the disease, the presence of complications, and the response to treatment. Mucosal healing in severe esophagitis is observed in 80% of patients treated with high-dose PPIs twice daily. If esophagitis remains untreated, the risk of malignant transformation from Barrett esophagus increases over time. However, with appropriate treatment, lifestyle modifications, and, in some cases, surgery, the prognosis for GERD is generally favorable.

Infection-Induced Ulcers

The prognosis of HSV and CMV infections in patients with good immunity is generally favorable, with the infection typically resolving within 1 to 2 weeks. The extent of ulceration on endoscopy is a poor prognostic indicator. However, in patients with compromised immunity, the prognosis is poorer due to a higher risk of severe complications, recurrent infections, and delayed diagnosis.[53][54] Esophageal candidiasis usually responds well to antifungal treatment, although the long-term sequelae of candidal esophagitis have not been well studied. Patients with underlying risk factors tend to have higher recurrence rates and may require alternative or prolonged antifungal therapy.

Ulcers from Caustic Ingestion

The prognosis after caustic ingestion depends on the severity of the injury, with morbidity and mortality rates remaining high. Patients with higher-grade injuries based on the Zargar classification scale are at greater risk for systemic complications and esophageal strictures, with grade 3 injuries presenting the highest risk for strictures.

The incidence of strictures has decreased over 80% (as reported by Zargar et al in 1991) to approximately 50% (as reported by Cheng et al in 2008). Improved outcomes may be attributed to developing and using more potent antiacid medications and more aggressive nasogastric irrigation.[55] In a national observational study conducted in France, 34% of patients experienced complications after ingestion. Surgery was required in 11% of patients due to digestive necrosis, and 8% of patients died. Multivariate analysis identified predictors of mortality, including older age, treatment at low-volume centers, intensive care unit admission, emergency surgery, and higher comorbidity scores.[56]

Ulcers Due to Dermatologic and Autoimmune Diseases

Esophageal manifestations of dermatologic diseases are rare but often associated with high morbidity and mortality rates. Pemphigus vulgaris has a mortality rate of 5% to 15%, with prognosis largely dependent on disease severity, response to treatment, and the presence of comorbidities.[57] Similarly, the prognosis of bullous pemphigoid is poor, with a 1-year mortality rate of 23%. Risk factors for poorer outcomes include advanced age, concomitant neurologic disorders, and elevated serum levels of anti-BP180, an autoantibody targeting hemidesmosomes in the basement membrane.[58]

Esophageal lichen planus is a potentially premalignant condition that can progress to SCC. Mutations in TP53 leading to overexpression have been linked to an increased risk of malignant transformation. However, further studies are needed to identify prognostic biomarkers for earlier detection. The risk of malignant transformation in esophageal lichen planus is currently estimated to be similar to that of oral lesions, around 1% to 3%.[59]

CGD is typically diagnosed in childhood, and data are limited on long-term outcomes in adults. Results from a retrospective study from a CGD clinic in the United Kingdom found that 43% of adult patients diagnosed in childhood had active gastrointestinal disease. Among patients with active gastrointestinal disease, 47% required surgical interventions, including colectomy, ileostomy, colostomy, proctectomy, fistula repair, and abscess drainage. Mortality in this cohort was primarily attributed to chronic respiratory failure rather than complications from gastrointestinal involvement. However, further studies are needed to better understand the prognosis of patients with CGD and esophageal manifestations.[60]

Data on esophageal Crohn disease and its prognostic implications are also limited. Factors influencing prognosis include the severity of the disease, treatment response, and the occurrence of subsequent complications. A retrospective multicenter case report found that 82.5% of patients achieved clinical remission within 7 months, with treatment options including PPIs, 5-aminosalicylic acid, systemic steroids, antitumor necrosis factor therapy, and thiopurines. Follow-up endoscopy in a subset of patients showed mucosal healing in 89.5% of cases. However, 7.5% of patients had recurrence after the initial treatment response.[61]

Malignancy-Related Ulcers

The prognosis of esophageal cancer is largely determined by the stage at diagnosis. Early detection and the extent of surgical resection are key factors for a more favorable outcome. Esophageal cancer is generally incurable but treatable. According to the National Cancer Institute, the 5-year relative survival rate for esophageal cancer is 21.6%. Patients diagnosed at an early, localized stage have a more favorable prognosis, with a 5-year relative survival rate of 48.1%. (National Cancer Institute: SEER Cancer Stat Facts: Esophageal Cancer. Bethesda, Md: National Cancer Institute. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/esoph.html)

Iatrogenic Ulcers

Factors determining the severity of thermal injury after pulmonary vein isolation depend on ablation energy, catheter characteristics, duration, and catheter-tissue contact force. The prognosis for post-variceal banding ulcer bleeding is poor, with mortality rates ranging from 22.3% to 23.8%. Poor prognostic indicators include high Model for End-Stage Liver Disease scores, emergent endoscopic band ligation, the presence of hepatocellular carcinoma, and active bleeding at the time of endoscopy.

Complications

Bleeding ulcers that present with large-volume hemorrhage can lead to hemodynamic instability and often require ICU admission, vasopressors for circulatory failure, ventilatory support, and renal replacement therapy. Postbanding ulcers are particularly at risk for hemorrhage and may result in exsanguination, as they are essentially variceal bleeds—a catastrophic complication of portal hypertension.

Strictures may warrant serial endoscopic dilation or stenting. Esophageal perforation requires urgent surgical evaluation, though select cases may benefit from stenting. Thermal injuries caused by atrial fibrillation ablation can lead to periesophageal nerve injury, resulting in esophageal and gastric hypomotility. Thermal injuries that progress to atrial-esophageal fistulas are often fatal. Mortality from esophageal ulcers is rare, with an estimated rate of 3.4%, according to a single retrospective observational study.

Consultations

Depending on the etiology of the esophageal ulcer and associated complications, various specialties may be involved in care delivery, including gastroenterology, infectious disease, dermatology, interventional radiology, critical care, and surgery.

Deterrence and Patient Education

According to a best practice advice statement in the 2022 American Gastroenterology Association (AGA) guidelines, clinicians should provide standardized educational materials to patients. These materials should cover the mechanism of GERD, lifestyle modifications, dietary behaviors, relaxation strategies, and the role of brain-gut axis relationships in the development of this condition. Both the 2022 American College of Gastroenterology and AGA guidelines recommend the following modifications to help minimize and control GERD symptoms:

- Implementing effective weight loss strategies for patients with obesity or overweight

- Avoiding meals before bedtime

- Eating smaller meals

- Avoiding tobacco products

- Avoiding "trigger foods," such as acidic or fatty foods, coffee, alcohol, chocolate, and carbonated drinks

- Elevating the head of bed if nighttime GERD symptoms are prevalent

- Sleeping left-side down

Individuals with pill esophagitis should receive counseling on proper pill-taking practices, including sitting upright while swallowing pills, taking them with a full glass of water, and remaining upright for at least 30 minutes before lying down. Clinicians should also consider alternative liquid formulations when available. For NSAID or medication-induced esophagitis, discontinuation of the offending agent and consideration of alternative medications are essential. In cases of caustic ingestion, a psychiatric evaluation may be necessary, particularly when nonaccidental ingestion is suspected. For all patients, treatment adherence is crucial for achieving and sustaining remission.

Pearls and Other Issues

Esophageal ulcers require a thorough and systematic approach to the differential diagnosis, guided by a detailed clinical history. While common causes should be prioritized, rarer etiologies, such as esophageal involvement in Crohn disease, must also be considered, even in the absence of a prior diagnosis. A careful review of the patient’s medication list, including over-the-counter drugs and supplements not documented in the electronic medical record, is essential, as is an assessment of medication administration habits. Additionally, a comprehensive social history can uncover risk factors for infections and immunosuppression. Key inquiries should address travel history, substance use, intravenous drug use, and sexual practices.

Diagnosing esophageal ulcers can be challenging, as ulcers from various etiologies often appear similar on endoscopy and pathology. Initial biopsies may yield nonspecific findings, making it difficult to determine the underlying cause. For persistent, nonhealing esophageal ulcers with unclear etiology, a repeat endoscopy with comprehensive sampling is recommended. The evaluation should include obtaining multiple biopsies from the ulcer margins, ulcer beds, and normal-appearing esophageal mucosa to maximize diagnostic yield. Further evaluation for underlying autoimmune conditions should be considered if common causes, such as infections, have been excluded.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Esophageal ulcers are uncommon and present diagnostic challenges due to their varied etiologies. Interprofessional care involving multiple specialties is crucial for improving patient outcomes and reducing morbidity and mortality. Early symptom recognition by primary care, emergency medicine, or urgent care providers can expedite referrals to gastroenterologists for timely endoscopic evaluation. Collaboration with additional specialists should be tailored to the underlying cause.

Dermatologists should be involved in treatment planning for autoimmune dermatologic diseases. Infectious disease consultation is essential for patients with immunocompromising conditions, such as HIV. An interprofessional team of surgeons, oncologists, radiologists, and gastroenterologists in malignancy cases is vital for developing a patient-centered treatment strategy. Toxicologists play a key role in managing caustic ingestion, particularly in cases of coingestion. Thoracic surgeons and interventional endoscopists should be consulted to provide specialized care for complications like esophageal perforation and strictures. After diagnosis and treatment, follow-up with a primary care physician or specialist is typically recommended to monitor symptom resolution and assess the need for repeat endoscopy, particularly in cases involving severe ulceration or an unclear etiology. Effective collaboration and coordination among specialists are essential to optimize patient outcomes and minimize the risk of complications.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Cohen DL, Bermont A, Richter V, Shirin H. Real world management of esophageal ulcers: analysis of their presentation, etiology, and outcomes. Acta gastro-enterologica Belgica. 2021 Jul-Sep:84(3):417-422. doi: 10.51821/84.3.004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34599565]

Higuchi D, Sugawa C, Shah SH, Tokioka S, Lucas CE. Etiology, treatment, and outcome of esophageal ulcers: a 10-year experience in an urban emergency hospital. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery : official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. 2003 Nov:7(7):836-42 [PubMed PMID: 14592655]

De Felice KM, Katzka DA, Raffals LE. Crohn's Disease of the Esophagus: Clinical Features and Treatment Outcomes in the Biologic Era. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2015 Sep:21(9):2106-13. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000469. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26083616]

Cazacu SM, Ghiluşi MC, Ivan ET, Ungureanu BS, Ciurea T, Săftoiu A, Dumitrescu CI, Forţofoiu M, Văduva IA, Neagoe CD. An unusual onset of Crohn's disease with oral aphthosis, giant esophageal ulcers and serological markers of cytomegalovirus and herpes virus infection: a case report and review of the literature. Romanian journal of morphology and embryology = Revue roumaine de morphologie et embryologie. 2019:60(2):659-665 [PubMed PMID: 31658341]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJain S, Dhingra S. Pathology of esophageal cancer and Barrett's esophagus. Annals of cardiothoracic surgery. 2017 Mar:6(2):99-109. doi: 10.21037/acs.2017.03.06. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28446998]

Domper Arnal MJ, Ferrández Arenas Á, Lanas Arbeloa Á. Esophageal cancer: Risk factors, screening and endoscopic treatment in Western and Eastern countries. World journal of gastroenterology. 2015 Jul 14:21(26):7933-43. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i26.7933. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26185366]

Rantanen TK, Sihvo EI, Räsänen JV, Hynninen M, Salo JA. Esophageal Ulcer as a Cause of Death: A Population-Based Study. Mortality of Esophageal Ulcer Disease. Digestion. 2015:91(4):272-6. doi: 10.1159/000381307. Epub 2015 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 25896262]

Richter JE, Rubenstein JH. Presentation and Epidemiology of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Gastroenterology. 2018 Jan:154(2):267-276. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.07.045. Epub 2017 Aug 3 [PubMed PMID: 28780072]

Hu SW, Chen AC, Wu SF. Drug-Induced Esophageal Ulcer in Adolescent Population: Experience at a Single Medical Center in Central Taiwan. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania). 2021 Nov 23:57(12):. doi: 10.3390/medicina57121286. Epub 2021 Nov 23 [PubMed PMID: 34946231]

Dağ MS, Öztürk ZA, Akın I, Tutar E, Çıkman Ö, Gülşen MT. Drug-induced esophageal ulcers: case series and the review of the literature. The Turkish journal of gastroenterology : the official journal of Turkish Society of Gastroenterology. 2014 Apr:25(2):180-4. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2014.5415. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25003679]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencede Brito Nunes M, Knecht M, Wiest R, Bosch J, Berzigotti A. Predictors and management of post-banding ulcer bleeding in cirrhosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Liver international : official journal of the International Association for the Study of the Liver. 2023 Aug:43(8):1644-1653. doi: 10.1111/liv.15621. Epub 2023 May 24 [PubMed PMID: 37222256]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDueñas E, Cachero A, Amador A, Rota R, Salord S, Gornals J, Xiol X, Castellote J. Ulcer bleeding after band ligation of esophageal varices: Risk factors and prognosis. Digestive and liver disease : official journal of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology and the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver. 2020 Jan:52(1):79-83. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2019.06.019. Epub 2019 Aug 6 [PubMed PMID: 31395524]

Chen S, Chun KRJ, Tohoku S, Bordignon S, Urbanek L, Willems F, Plank K, Hilbert M, Konstantinou A, Tsianakas N, Bologna F, Kreuzer C, Trolese L, Schmidt B. Esophageal Endoscopy After Catheter Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation Using Ablation-Index Guided High-Power: Frankfurt AI-HP ESO-I. JACC. Clinical electrophysiology. 2020 Oct:6(10):1253-1261. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2020.05.022. Epub 2020 Aug 12 [PubMed PMID: 33092751]

Pimentel AM, Rocha R, Santana GO. Crohn's disease of esophagus, stomach and duodenum. World journal of gastrointestinal pharmacology and therapeutics. 2019 Mar 7:10(2):35-49. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v10.i2.35. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30891327]

Arar AM, DeLay K, Leiman DA, Menard-Katcher P. Esophageal Manifestations of Dermatological Diseases, Diagnosis and Management. Current treatment options in gastroenterology. 2022 Dec:20(4):513-528. doi: 10.1007/s11938-022-00399-6. Epub 2022 Oct 18 [PubMed PMID: 37287750]

Khangura SK, Kamal N, Ho N, Quezado M, Zhao X, Marciano B, Simpson J, Zerbe C, Uzel G, Yao MD, DeRavin SS, Hadigan C, Kuhns DB, Gallin JI, Malech HL, Holland SM, Heller T. Gastrointestinal Features of Chronic Granulomatous Disease Found During Endoscopy. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2016 Mar:14(3):395-402.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.10.030. Epub 2015 Nov 9 [PubMed PMID: 26545803]

Fujiwara S, Shimizu I, Ishikawa M, Uehara K, Yamamoto H, Okazaki M, Horie T, Iuchi A, Ito S. Intestinal Behcet's disease with esophageal ulcers and colonic longitudinal ulcers. World journal of gastroenterology. 2006 Apr 28:12(16):2622-4 [PubMed PMID: 16688814]

Jia N, Tang Y, Liu H, Li Y, Liu S, Liu L. Rare esophageal ulcers related to Behçet disease: A case report. Medicine. 2017 Nov:96(44):e8469. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000008469. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29095300]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKawabata H, Miyata M, Kawaguchi Y, Ueda M, Uno K, Tanaka K, Cho E, Yasuda K, Nakajima M. Intestinal Behçet's disease with an esophageal ulcer. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2003 Jul:58(1):151-4 [PubMed PMID: 12838248]

Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2024 Jan-Feb:74(1):12-49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21820. Epub 2024 Jan 17 [PubMed PMID: 38230766]

Martinsen TC, Fossmark R, Waldum HL. The Phylogeny and Biological Function of Gastric Juice-Microbiological Consequences of Removing Gastric Acid. International journal of molecular sciences. 2019 Nov 29:20(23):. doi: 10.3390/ijms20236031. Epub 2019 Nov 29 [PubMed PMID: 31795477]

Mikami DJ, Murayama KM. Physiology and pathogenesis of gastroesophageal reflux disease. The Surgical clinics of North America. 2015 Jun:95(3):515-25. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2015.02.006. Epub 2015 Mar 24 [PubMed PMID: 25965127]

Mousa H, Hassan M. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Pediatric clinics of North America. 2017 Jun:64(3):487-505. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2017.01.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28502434]

De Giorgi F, Palmiero M, Esposito I, Mosca F, Cuomo R. Pathophysiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Acta otorhinolaryngologica Italica : organo ufficiale della Societa italiana di otorinolaringologia e chirurgia cervico-facciale. 2006 Oct:26(5):241-6 [PubMed PMID: 17345925]

Tack J, Pandolfino JE. Pathophysiology of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Gastroenterology. 2018 Jan:154(2):277-288. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.09.047. Epub 2017 Oct 14 [PubMed PMID: 29037470]

Hill LD, Kozarek RA, Kraemer SJ, Aye RW, Mercer CD, Low DE, Pope CE 2nd. The gastroesophageal flap valve: in vitro and in vivo observations. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 1996 Nov:44(5):541-7 [PubMed PMID: 8934159]

Canalejo E, García Durán F, Cabello N, García Martínez J. Herpes esophagitis in healthy adults and adolescents: report of 3 cases and review of the literature. Medicine. 2010 Jul:89(4):204-210. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181e949ed. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20616659]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBaroco AL, Oldfield EC. Gastrointestinal cytomegalovirus disease in the immunocompromised patient. Current gastroenterology reports. 2008 Aug:10(4):409-16 [PubMed PMID: 18627655]

De Lusong MAA, Timbol ABG, Tuazon DJS. Management of esophageal caustic injury. World journal of gastrointestinal pharmacology and therapeutics. 2017 May 6:8(2):90-98. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v8.i2.90. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28533917]

Matsumoto Y, Kaneshiro T, Hijioka N, Nodera M, Yamada S, Kamioka M, Yoshihisa A, Ohkawara H, Hikichi T, Suzuki H, Takeishi Y. Predicting factors of transmural thermal injury after cryoballoon pulmonary vein isolation. Journal of interventional cardiac electrophysiology : an international journal of arrhythmias and pacing. 2019 Mar:54(2):101-108. doi: 10.1007/s10840-018-0454-8. Epub 2018 Sep 19 [PubMed PMID: 30232688]

Misiak P, Jabłoński S, Piskorz Ł, Dorożała L, Terlecki A, Wcisło S. Oesophageal perforation - therapeutic and diagnostics challenge. Retrospective, single-center case report analysis (2009-2015). Polski przeglad chirurgiczny. 2017 Aug 31:89(4):1-4. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0010.3899. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28905806]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDecker A, Schauer F, Lazaro A, Monasterio C, Schmidt AR, Schmitt-Graeff A, Kreisel W. Esophageal lichen planus: Current knowledge, challenges and future perspectives. World journal of gastroenterology. 2022 Nov 7:28(41):5893-5909. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v28.i41.5893. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36405107]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePetagna L, Antonelli A, Ganini C, Bellato V, Campanelli M, Divizia A, Efrati C, Franceschilli M, Guida AM, Ingallinella S, Montagnese F, Sensi B, Siragusa L, Sica GS. Pathophysiology of Crohn's disease inflammation and recurrence. Biology direct. 2020 Nov 7:15(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s13062-020-00280-5. Epub 2020 Nov 7 [PubMed PMID: 33160400]

Kaneshiro T, Takeishi Y. Esophageal thermal injury in catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. Fukushima journal of medical science. 2021 Dec 21:67(3):95-101. doi: 10.5387/fms.2021-23. Epub 2021 Nov 20 [PubMed PMID: 34803083]

Salame M, Jawhar N, Belluzzi A, Al-Kordi M, Storm AC, Abu Dayyeh BK, Ghanem OM. Marginal Ulcers after Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass: Etiology, Diagnosis, and Management. Journal of clinical medicine. 2023 Jun 28:12(13):. doi: 10.3390/jcm12134336. Epub 2023 Jun 28 [PubMed PMID: 37445371]

Kim JW, Kim BG, Kim SH, Kim W, Lee KL, Byeon SJ, Choi E, Chang MS. Histomorphological and Immunophenotypic Features of Pill-Induced Esophagitis. PloS one. 2015:10(6):e0128110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128110. Epub 2015 Jun 5 [PubMed PMID: 26047496]

Dafoe CS, Ross CA. Acute corrosive oesophagitis. Thorax. 1969 May:24(3):291-4 [PubMed PMID: 5810370]

Marshall JB, Singh R, Demmy TL, Bickel JT, Everett ED. Mediastinal histoplasmosis presenting with esophageal involvement and dysphagia: case study. Dysphagia. 1995 Winter:10(1):53-8 [PubMed PMID: 7859535]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWang HW, Kuo CJ, Lin WR, Hsu CM, Ho YP, Lin CJ, Su MY, Chiu CT, Chen KH. Clinical Characteristics and Manifestation of Herpes Esophagitis: One Single-center Experience in Taiwan. Medicine. 2016 Apr:95(14):e3187. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003187. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27057845]

Monteiro S, Moreira MJ, Ribeiro JM, Cotter J. Oesophageal presentation of Crohn's disease. BMJ case reports. 2017 Jan 16:2017():. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-217960. Epub 2017 Jan 16 [PubMed PMID: 28093426]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMurro D, Jakate S. Radiation esophagitis. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2015 Jun:139(6):827-30. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2014-0111-RS. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26030254]

Ogawa S, Kawakami H, Suzuki S, Kuroki D, Uchiyama N, Hatada H, Gi T, Sato Y. Metachronous Esophageal Ulcers after Immune-mediated Colitis Due to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy: A Case Report and Literature Review. Internal medicine (Tokyo, Japan). 2021 Sep 1:60(17):2783-2791. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.6606-20. Epub 2021 Mar 22 [PubMed PMID: 33746162]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJung KH, Choi J, Gong EJ, Lee JH, Choi KD, Song HJ, Lee GH, Jung HY, Chong YP, Lee SO, Choi SH, Kim YS, Woo JH, Kim DH, Kim SH. Can endoscopists differentiate cytomegalovirus esophagitis from herpes simplex virus esophagitis based on gross endoscopic findings? Medicine. 2019 Jun:98(23):e15845. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000015845. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31169688]

ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Sharaf RN, Shergill AK, Odze RD, Krinsky ML, Fukami N, Jain R, Appalaneni V, Anderson MA, Ben-Menachem T, Chandrasekhara V, Chathadi K, Decker GA, Early D, Evans JA, Fanelli RD, Fisher DA, Fisher LR, Foley KQ, Hwang JH, Jue TL, Ikenberry SO, Khan KM, Lightdale J, Malpas PM, Maple JT, Pasha S, Saltzman J, Dominitz JA, Cash BD. Endoscopic mucosal tissue sampling. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2013 Aug:78(2):216-24. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.04.167. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23867371]

Zargar SA, Kochhar R, Mehta S, Mehta SK. The role of fiberoptic endoscopy in the management of corrosive ingestion and modified endoscopic classification of burns. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 1991 Mar-Apr:37(2):165-9 [PubMed PMID: 2032601]

Debi U, Sharma M, Singh L, Sinha A. Barium esophagogram in various esophageal diseases: A pictorial essay. The Indian journal of radiology & imaging. 2019 Apr-Jun:29(2):141-154. doi: 10.4103/ijri.IJRI_465_18. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31367085]

Katz PO, Dunbar KB, Schnoll-Sussman FH, Greer KB, Yadlapati R, Spechler SJ. ACG Clinical Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2022 Jan 1:117(1):27-56. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001538. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34807007]

Chen JW, Vela MF, Peterson KA, Carlson DA. AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Diagnosis and Management of Extraesophageal Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: Expert Review. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2023 Jun:21(6):1414-1421.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.01.040. Epub 2023 Apr 14 [PubMed PMID: 37061897]

Li L, Chakinala RC. Cytomegalovirus Esophagitis. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32310570]

Mohamed AA, Lu XL, Mounmin FA. Diagnosis and Treatment of Esophageal Candidiasis: Current Updates. Canadian journal of gastroenterology & hepatology. 2019:2019():3585136. doi: 10.1155/2019/3585136. Epub 2019 Oct 20 [PubMed PMID: 31772927]

Neff AG, Turner M, Mutasim DF. Treatment strategies in mucous membrane pemphigoid. Therapeutics and clinical risk management. 2008 Jun:4(3):617-26 [PubMed PMID: 18827857]

Chang S, Park SJ, Kim SW, Jin MN, Lee JH, Kim HJ, Hong SP, Kim TI. Esophageal involvement of pemphigus vulgaris associated with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Clinical endoscopy. 2014 Sep:47(5):452-4. doi: 10.5946/ce.2014.47.5.452. Epub 2014 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 25325007]

Ali AA, Anasseri S, Abou-Ghaida J, Walker L, Barber T. Cytomegalovirus Esophagitis in an Immunocompromised Patient. Cureus. 2023 Sep:15(9):e45634. doi: 10.7759/cureus.45634. Epub 2023 Sep 20 [PubMed PMID: 37868477]

Custódio SF, Félix C, Cruz F, Veiga MZ. Herpes simplex virus esophagitis-clinical challenges in the elderly. BMJ case reports. 2021 Apr 7:14(4):. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-240956. Epub 2021 Apr 7 [PubMed PMID: 33827878]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCheng HT, Cheng CL, Lin CH, Tang JH, Chu YY, Liu NJ, Chen PC. Caustic ingestion in adults: the role of endoscopic classification in predicting outcome. BMC gastroenterology. 2008 Jul 25:8():31. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-8-31. Epub 2008 Jul 25 [PubMed PMID: 18655708]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChalline A, Maggiori L, Katsahian S, Corté H, Goere D, Lazzati A, Cattan P, Chirica M. Outcomes Associated With Caustic Ingestion Among Adults in a National Prospective Database in France. JAMA surgery. 2022 Feb 1:157(2):112-119. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.6368. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34878529]

Del Castillo JRF, Yousaf MN, Chaudhary FS, Saleh N, Mills L. Esophageal Pemphigus Vulgaris: A Rare Etiology of Upper Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage. Case reports in gastrointestinal medicine. 2021:2021():5555961. doi: 10.1155/2021/5555961. Epub 2021 Mar 18 [PubMed PMID: 33791134]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCastelo Branco C, Fonseca T, Marcos-Pinto R. Esophageal Bullous Pemphigoid. European journal of case reports in internal medicine. 2022:9(2):003160. doi: 10.12890/2022_003160. Epub 2022 Feb 1 [PubMed PMID: 35265547]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOliveira JP, Uribe NC, Abulafia LA, Quintella LP. Esophageal lichen planus. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia. 2015 May-Jun:90(3):394-6. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153255. Epub 2015 Jun 1 [PubMed PMID: 26131872]

Campos LC, Di Colo G, Dattani V, Braggins H, Kumararatne D, Williams AP, Alachkar H, Jolles S, Battersby A, Cole T, Elcombe S, Gilmour KC, Goldblatt D, Gennery AR, Haddock J, Lowe DM, Burns SO. Long-term outcomes for adults with chronic granulomatous disease in the United Kingdom. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2021 Mar:147(3):1104-1107. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.08.034. Epub 2020 Sep 21 [PubMed PMID: 32971110]

Vale Rodrigues R, Sladek M, Katsanos K, van der Woude CJ, Wei J, Vavricka SR, Teich N, Ellul P, Savarino E, Chaparro M, Beaton D, Oliveira AM, Fragaki M, Shitrit AB, Ramos L, Karmiris K, ECCO CONFER investigators. Diagnosis and Outcome of Oesophageal Crohn's Disease. Journal of Crohn's & colitis. 2020 Jun 19:14(5):624-629. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz201. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31837220]