Introduction

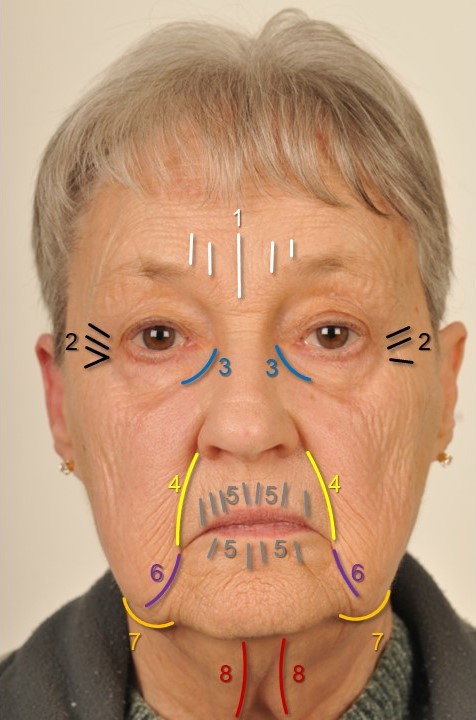

Facelifting, also known as rhytidectomy, was the third most commonly performed cosmetic surgical procedure in the United States in 2020, following rhinoplasty and blepharoplasty. The popularity of facelifting has remained constant for decades due to the significant impact that facial aging has on self-esteem and perceptions of youth, health, success, and attractiveness.[1] Aging leads to descent of the facial skin and soft tissues, along with lipoatrophy and bony resorption that lead to tear trough deformities, deep palpebromalar grooves, loss of malar volume, descent of the jowls, pronounced nasolabial folds, and development of marionette lines (see Image. Stigmata of the Aging Face). When performed appropriately, facelifting repositions descended soft tissue superiorly to restore facial volume and a more youthful appearance. The earliest described facelifts, as described by Höllander in 1901, involved simple cutaneous excision and skin tightening. Over the past century, techniques have evolved to include simple and extended manipulation of the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS), mobilization of the malar and sub-orbicularis oculi fat, and minimal access suture suspension options, with each of these methods able to be tailored to the individual patient's needs and the surgeon's expertise.[2][3][4][5] The extended SMAS facelift technique dissects the SMAS more thoroughly and distally than other techniques, providing excellent access to the anterior jawline and neck to reduce jowling, submental fullness, and platysmal banding. Midface rejuvenation may also be achieved by combining extended SMAS dissection with deep plane facelift, wherein ptotic midfacial soft tissue is resuspended superiorly to restore facial volume and create a more youthful appearance.[6][7]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

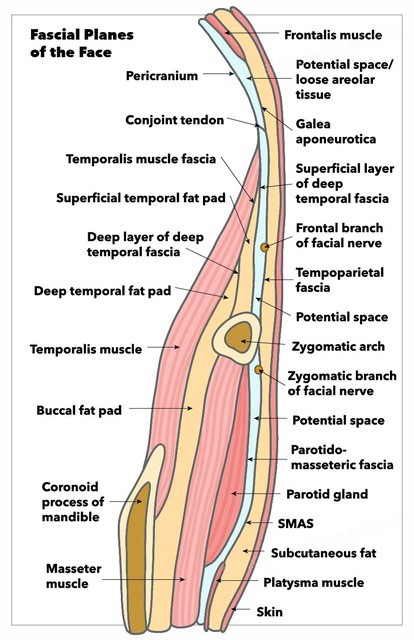

The head and neck region comprises 5 important fascial layers, with which any surgeon working in the area must be very familiar. From superficial to deep, these layers are the skin, the subcutaneous tissue/superficial areolar tissue, the superficial fascia, the loose areolar tissue, and the deep fascia (see Image. Fascial Planes of the Face and Musculature).[8] At the level of the midface, the superficial fascia is termed the SMAS. The nomenclature of this layer varies depending on the region of the face; it is referred to as the frontalis muscle in the forehead, the galea aponeurotica in the scalp, the temporoparietal fascia in the temporal region, the SMAS in the midface, and the platysma in the neck. The deep fascial layers also have different names depending on their location in the face and neck—the deep temporal fascia or temporalis muscle fascia in the temporal region, the parotidomasseteric fascia in the midface, the pericranium in the scalp, and the deep cervical investing fascia in the neck. At several points in the face, these fascial layers coalesce, making dissection between planes difficult. Between the temporal and frontal regions, the frontalis muscle and the pericranium medially condense down onto the skull at the conjoint tendon along the periphery of the temporalis muscle, where they meet the temporoparietal and temporalis muscle fasciae laterally. Similarly, the temporoparietal fascia and the superficial layer of the deep temporal fascia join the periosteum of the zygomatic arch superiorly, whereas the SMAS and parotid fascia approach from below.

The SMAS varies in thickness within the face, with denser tissue laterally and thinner tissue medially. SMAS adheres tightly to the dermis, but more loosely to the areolar tissue and parotidomasseteric fascia beneath, which facilitates blunt sub-SMAS dissection. The elevation and repositioning of a SMAS flap, separately from the facial skin, is what permits modern facelifting techniques to provide patients with stable, long-term rejuvenation.[9] Fibrous connections that support and stabilize the facial soft tissues perforate the SMAS at consistent points. There are 2 types of fibrous connections—the osseocutaneous ligaments and the ligaments that connect the superficial and deep fascial layers. These ligaments are surgically released during facelifting to allow mobilization of the soft tissues, and their function is then restored with sutures.[7] The most important ligaments in the face include the temporal ligamentous adhesion, the lateral orbital thickening, the zygomatic ligament (also known as the patch of McGregor), the masseteric ligaments, and the mandibular ligament. Additional soft tissue structures that may be manipulated during extended SMAS facelifting include the malar fat pad and the buccal fat pad. The malar fat pad provides youthful volume to the upper cheeks, ideally sitting atop the zygomaticus muscles, superior to the nasolabial fold. On the other hand, the buccal fat pad lies deep to the SMAS and must be either accessed between branches of the facial nerve or approached intraorally if the patient desires slimming of the lower midface.

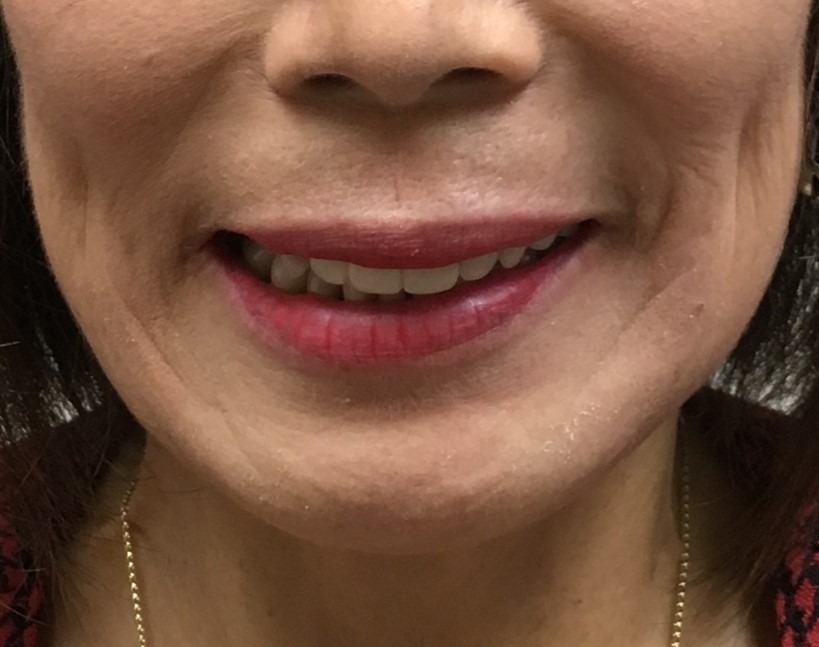

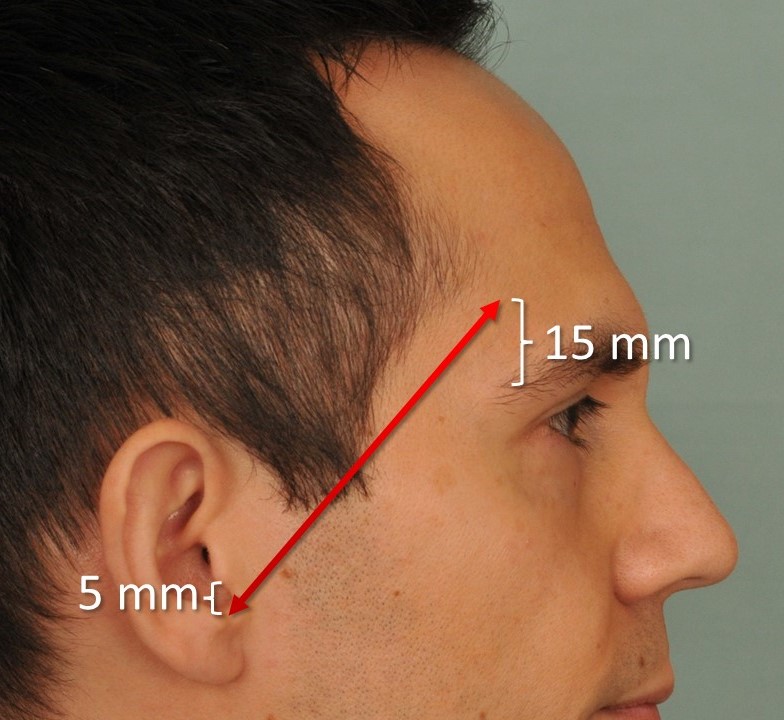

Running deep to the SMAS and superficial to the parotidomasseteric fascia are the main extratemporal branches of the facial nerve—the frontal, zygomatic, buccal, marginal mandibular, and cervical. These nerves exit the anterior surface of the parotid gland and course anteriorly to innervate the muscles of facial expression. The nerve branches generally enter the deep surfaces of the facial muscles, except for the mentalis, levator anguli oris, and buccinator muscles, which are innervated from their superficial surfaces because they are located deeper within the face. This arrangement is crucial to keep in mind to prevent nerve injury during the dissection process. Awareness of each branch’s trajectory through the face is equally essential. The frontal and marginal mandibular branches are the most likely to be injured, but their anatomical courses are relatively consistent (see Image. Left Marginal Mandibular Nerve Injury).[10] The frontal branch follows the line of Pitanguy between a point 5 mm inferior to the tragus and a point 15 mm superior to the lateral brow (see Image. Pitanguy's Line).[11] Thus, avoiding deep dissection over the central third of the zygomatic arch should preserve motor function to the upper face. The marginal mandibular branch is closely associated with the facial vein and is reliably found within the subplatysmal fat superior to the margin of the mandible, anterior to the gonial notch. Posterior to the gonial notch, it is most likely to be located superior to the margin of the mandible as well, but may be inferior to it in 20% of patients.[12] However, the great auricular nerve is more commonly injured than the facial nerve's branches, which exits the posterior aspect of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) and travels superiorly roughly mid-way between the mastoid tip and the angle of the mandible, 1 to 2 cm posterior to the external jugular vein (see Image. Great Auricular Nerve). The great auricular nerve can be located reliably at a point 6.5 cm inferior to the external auditory meatus (the point of McKinney), overlying the middle portion of the SCM, where it is most superficial and therefore most liable to be injured iatrogenically.[13]

Indications

Any patient with signs of facial aging and an interest in surgical rejuvenation may be considered a candidate for surgery. The extended SMAS facelifting technique is particularly effective in addressing the lower face and neck, including the jowls, submental fat, hypertrophied anterior digastric muscles, and ptotic submandibular glands. The procedure is typically paired with cervicoplasty, including platysmal plication with or without transverse myotomy.[14] Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Neck Rejuvenation," for further information. Patients with loss of malar volume, malar fat pad ptosis, or deep nasolabial folds are also candidates for the addition of midface lifting or deep plane facelifting to the procedure, thus making the operation a hybrid facelift. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Deep Plane Facelift," for further information.

Contraindications

There are several relative contraindications for facelifting using the extended SMAS technique. Examples include nicotine use, keloid formation, anticoagulation therapy, uncontrolled hypertension, and having unrealistic expectations.[15][16] Some patients may benefit more from other facelift techniques rather than the extended SMAS lift.[17] For instance, patients with midfacial aging but no jowling or platysmal banding should be offered a midface lift instead. A comprehensive preoperative assessment should also include evaluation of psychiatric comorbidities, medical contraindications, and life circumstances or social situations that could increase the risk of complications. Patients with a narcissistic personality disorder, body dysmorphic disorder, and other mental health disorders should seek psychiatric evaluation and treatment before surgery or even avoid cosmetic procedures entirely. The high incidence of postoperative depression that occurs with facelifting means that patients with a history of depression should be counseled appropriately, and the procedure should be delayed if pharmacotherapy needs to be initiated preoperatively.[18]

Equipment

Although instrument sets may vary by surgeon and institution, extended SMAS rhytidectomy typically requires the following tools:

- #10 and #15 blade scalpels

- A light source

- A facelift retractor, such as Tebbets, Ferreira, or similar

- Facelift scissors such as Gorney-Freeman, Kaye, Goldman-Fox, and Castañares

- Trepsat dissectors

- Needle drivers, such as Halsey, Olsen-Hegar, or similar

- Forceps, such as Adson-Brown and DeBakey

- Electrocautery

- Goodhill suction

- Suture scissors

- Sutures for both soft tissue suspension and skin closure

Heavy 2-0 polyglactin sutures are used to suspend the SMAS flap. Finer 5-0 or 6-0 polypropylene or nylon sutures are used for skin closure anterior to the auricle, and 4-0 to 6-0 absorbable sutures, such as plain gut, are used to close the remainder of the incision. A bulky compression dressing, with or without suction drains, is typically applied after the procedure, and some surgeons also employ fibrin glue.

Personnel

Due to the complex nature of this procedure and the fact that facelifting is often accompanied by other cosmetic surgical procedures, such as blepharoplasty, liposuction, skin resurfacing, and brow lifting, general anesthesia or deep sedation is preferred. In addition to the anesthesia provider, an operating room nurse and a surgical technician are required, and a first assistant helps expedite the procedure. Postoperatively, outpatient nursing staff play a critical role in wound care, suture removal, and patient support.

Preparation

In preparation for facelifting, patients should be encouraged to stop smoking at least 4 weeks before the surgery. Patients should also be instructed to discontinue any anticoagulation, if possible, before surgery to minimize the risk of postoperative hematoma formation and reduce intraoperative blood loss. During the preoperative visit, the surgeon should document any facial asymmetry and assess the preoperative function of cranial nerves V and VII. Assessment of the great auricular nerve function is particularly important for patients who have undergone prior face or neck lifting. If prior rhytidectomy has been performed, any resulting asymmetries or deformities should be documented and photographed. Examples include the cobra neck deformity, pixie ear deformity, frontal and marginal mandibular branch motor nerve injuries, and any suboptimal scarring. Standard preoperative photography for all facelifting patients should include frontal and profile views, which should be printed and posted in the operating room for reference during surgery.

All preoperative markings should be made with the patient in an upright position to accurately assess soft tissue descent due to gravity. Marking any platysmal banding may be helpful, and some surgeons may also circle the malar fat pads and trace the tear troughs. If periocular surgery is performed concurrently, the upper eyelid creases, the extent of lateral lid hooding, and the peaks of the eyebrows may also be marked.

Technique or Treatment

For extended SMAS facelifting, the patient should be placed in a supine position at a height appropriate for seated surgery. If possible, the operating table should be rotated 90° to 180° to provide the surgeon with more ergonomic access to the patient's head. After protecting the eyes and cleansing the face, the patient is draped. If an endotracheal tube is present, it may be sutured to the teeth to allow the airway circuit to be moved periodically during the case, facilitating access to the face and neck. Lidocaine with epinephrine is often injected along the planned incisions, and tumescent solution is infiltrated into the plane of the intended flap elevation to achieve hydrodissection and hemostasis while limiting the need for intraoperative opioid administration. Importantly, injecting too much volume distorts the soft tissues and should be avoided. A typical tumescent solution may contain 12.5 mL of 1% lidocaine, 12.5 mL of 0.25% bupivicaine, 1 mL of 1:1000 epinephrine, and 250 mg of tranexamic acid mixed in 250 mL of saline.[19]

A beveled incision is made at the temporal hair tuft to preserve hair follicles. Electrocautery in coagulation mode can be used for hemostasis, with care taken to avoid the hair follicles to prevent alopecia. The incision then travels caudally into a posttragal incision in females, curves around the ear into the postauricular sulcus, and runs along the posterior hairline (see Images. Blair Rhytidectomy Incision Marking Demonstrating the Post-Tragal Approach in a Female Patient and Blair Rhytidectomy Incision Marking Demonstrating the Postauricular Aspect of the Incision). Male patients should be informed that posttragal incisions bring bearded skin onto the tragus, making an incision placed approximately 1 cm anterior to the base of the tragus preferable in most cases, despite the more visible scar that results.

After the incision is completed, a skin flap is elevated anteriorly towards the cheek and inferiorly from the mastoid towards the neck; this dissection takes place subcutaneously, superficial to the SMAS. Flap dissection is, on average, carried out 4 cm radially from the inferior aspect of the tragus. Raising this flap too thick may lead to a weak SMAS flap, whereas raising it too thin may compromise the skin's vascularity. Care must also be taken to avoid damage to the great auricular nerve, which crosses the SCM posterior to the platysma. Jowl fat should be kept in continuity with the SMAS so that it can be repositioned cephalad later when raising the SMAS flap.[7] Limiting the extent of subcutaneous elevation to no more than necessary reduces complications by preserving a more robust blood supply to the facial skin.[20]

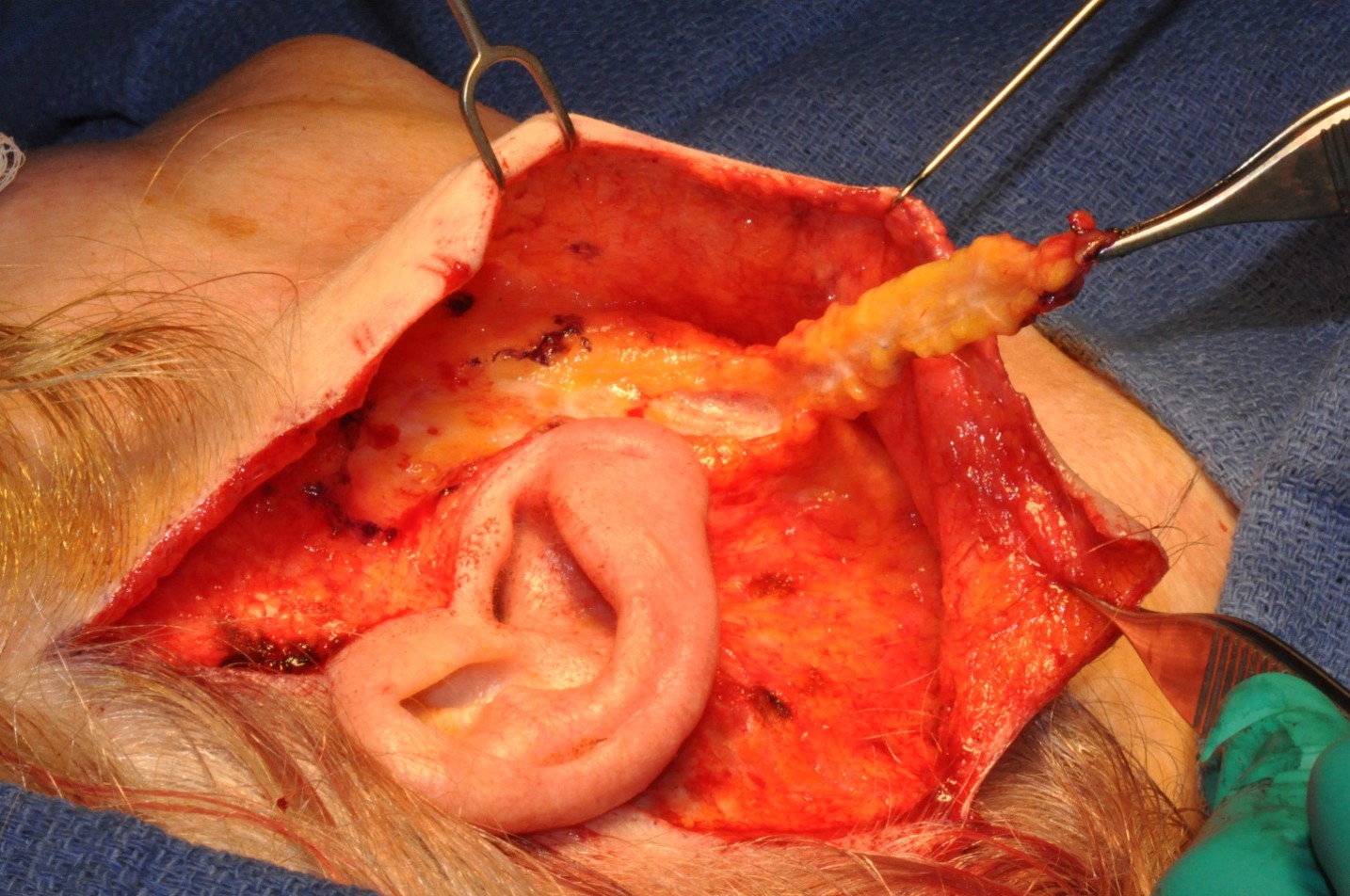

After the skin flap is raised, the SMAS is incised and elevated. In the technique described by Quatela and colleagues, this incision is made vertically, approximately 2 cm anterior to the tragus, which allows for the development of a plane deep to the SMAS and inferior to the zygomatic arch, as well as the elevation of a thin, inferiorly based SMAS flap. This finger or tongue of SMAS is subsequently transposed beneath the ear and suspended posteriorly onto the mastoid, applying tension along the vector of the mandibular margin to efface the jowls (see Images. Inferiorly Based SMAS Flap, Extending from Zygomatic Arch to Mandibular Angle and SMAS Flap Transposition to Mastoid, Tightening Mandible Contour and Effacing Jowl).[6] Continuing the sub-SMAS plane of dissection anteriorly elevates the orbicularis oculi muscle and the malar fat pad into the skin flap and exposes the superficial surface of the zygomaticus major muscle. Doing so allows lifting of the midfacial fat, adding a deep-plane component to the extended SMAS facelift without manipulating tissue in the vicinity of the frontal branch of the facial nerve, which passes over the middle third of the zygomatic arch (see Image. Deep Plane Rhytidectomy).[21] This maneuver is considered an integral part of the extended SMAS rhytidectomy technique by some authors. In contrast, others view it as an optional addition that makes the lift a hybrid procedure suitable for certain patients.[7][6] Most of the sub-SMAS dissection can be carried out with careful spreading of facelift scissors or the Trepsat facial dissectors. Regardless of whether the malar fat pad is addressed during the procedure, dividing the zygomatic and masseteric cutaneous ligaments is crucial for mobilizing the SMAS sufficiently to achieve a cosmetically pleasing and long-lasting lift. Once platysmal muscle fibers are identified at the inferior extent of the incision, blunt dissection may extend in this sub-SMAS or submuscular plane past the body of the mandible and into the neck, exposing the submandibular glands. These glands may require judicious debulking to prevent submandibular fullness after the platysma is suspended. However, care must be taken to avoid injury to the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve during this maneuver. This subplatysmal elevation places the facial vessels and the lower division of the facial nerve at risk of injury, which is why this dissection is typically performed bluntly. Alternatively, the cervical dissection may be performed in a subcutaneous plane to reduce the risk of nerve injury and facilitate the division of the mandibular cutaneous ligaments that produce marionette lines. If a subcutaneous neck elevation is employed, an additional short submental incision permits access to the anterior digastric muscles and central subplatysmal or submental fat, which can then be reduced as necessary. Over-resection of submental fat should be avoided, as it may cause prominence of the anterior digastric muscles and result in a cobra-neck deformity. Anteriorly, the sub-SMAS dissection ends lateral to the oral commissure, affording access to the buccal fat pad, or boule of Bichat, for debulking if necessary. Care must be taken when addressing the buccal fat pad, as the distal midfacial branches of the facial nerve course superficially over it.

After completion of the SMAS dissection, the SMAS flap is anchored anteriorly to the pretragal area and posteriorly to the mastoid periosteum. A thick suture, such as 2-0 polyglactin, is typically used for SMAS suspension. About 10 to 12 stitches are placed on each side, fixating the SMAS and platysma. Careful trimming of the jowl and submandibular fat at this time enhances jawline definition. The skin is then assessed for dimples; occasionally, additional subcutaneous dissection must be performed to smooth the contour. Careful application of bipolar cautery is used for hemostasis, if necessary. An assistant should watch the patient's face for movement during diathermy to prevent nerve injury. Excess skin is excised with a #15 blade as the final closure is begun. Burow's triangles may be used to bring the skin edges together smoothly, if required. The incision is closed by placing 5-0 polypropylene stay sutures at the root of the helix and the cephalad part of the postauricular incision. The remaining incisions are then closed according to the surgeon's preference. Typically, 4-0, 5-0, or 6-0 absorbable sutures are utilized, with staples sometimes used in the hair-bearing scalp. After the hair is washed, a topical antibiotic is applied to the incision sites, and a bulky compression dressing is applied.[7][22] Some surgeons also place suction drains to prevent the development of a hematoma or use fibrin glue to eliminate subcutaneous dead space. Regardless of the adjunctive measures employed, the most effective means of preventing postoperative bleeding is maintaining a systolic blood pressure below 120 mmHg and prophylactically addressing pain and nausea, which also likely serves to reduce hypertension.[16][23][16]

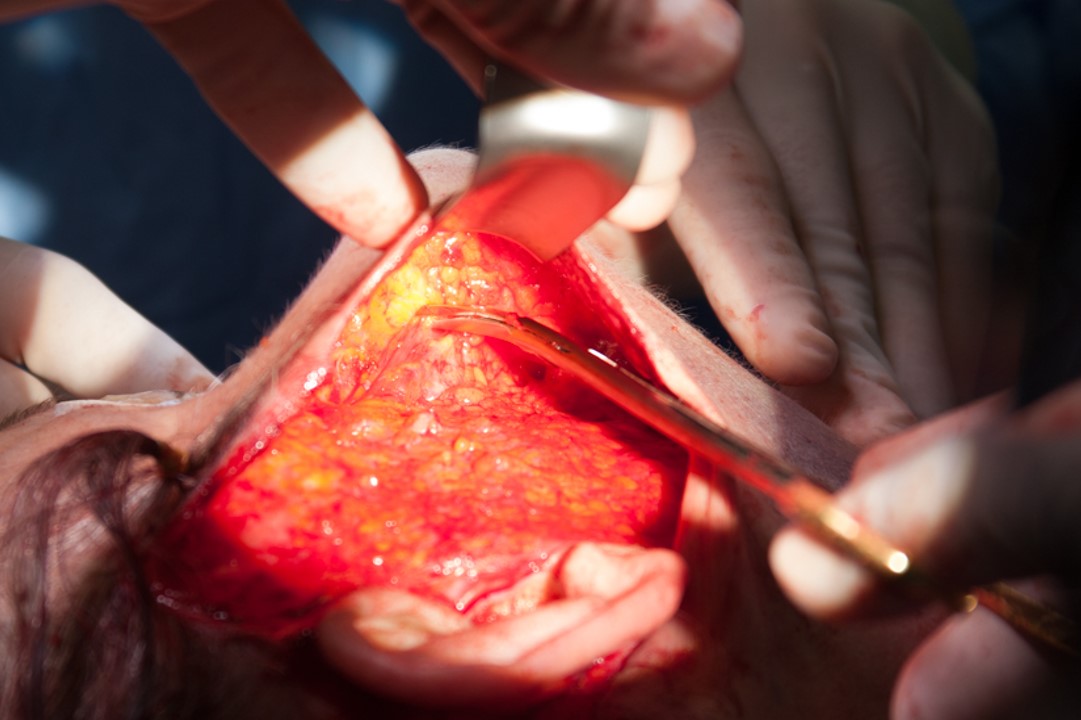

Complications

Complications associated with the extended SMAS facelift are similar to those of other rhytidectomies. The most common is patient dissatisfaction with the cosmetic outcome. Other potential complications include postoperative bleeding, hematoma, seroma or sialocele formation, ecchymosis, edema, great auricular or facial nerve branch damage, skin necrosis (see Image. Full-Thickness Necrosis of the Skin Flap), unfavorable scarring, hairline alteration, alopecia, pixie ear deformity (see Image. Pixie Ear Deformity), winged tragus, cobra neck deformity (see Image. Cobra neck Deformity), and depression.[7][18] Hematomas are relatively common, and most can be managed with aspiration in an outpatient setting. However, large and expanding hematomas are best addressed in the operating room (see Image. Upper Neck Hematoma). Men are more likely to develop hematomas than women due to the more robust cutaneous blood supply they possess to support facial hair growth; hypertension is also a major contributing factor, with a systolic blood pressure of >120 to 140 mmHg after surgery more likely to result in postoperative bleeding.[16][23] Effective management of pain, nausea, and vomiting is the most effective means of preventing hematomas after facelifting, even more effective than the placement of suction drains or a compressive dressing.[24]

Clinical Significance

Every facelift operation performed must be tailored to the patient's specific anatomy and goals. The extended SMAS technique is most suitable for individuals who would benefit predominantly from the correction of jowls and submental fullness, while also providing access for additional procedures, such as platysmaplasty and midface lifting. The resilience of the SMAS and its resistance to elongation under tension produce a facelift with excellent stability and consistent long-term results.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Although facelifting is a commonly performed procedure, it is time-intensive and demands meticulous execution to achieve the patient's aesthetic goals while minimizing the risk of complications. Permanent motor nerve injuries are rare, but hypesthesia from sensory nerve damage is comparatively common. Bleeding complications, such as hematoma formation, and dissatisfaction with the result or even transient postoperative depression are often encountered as well. The responsibility for preventing adverse outcomes, with respect to the technical aspects of the operation, rests with the surgeon, who must carry out the facelift painstakingly and efficiently. The surgeon is also responsible for identifying medical and psychiatric comorbidities preoperatively and ensuring that any perioperative effects they may have are mitigated to the greatest extent possible or that surgery is not offered. However, even a flawless operation may result in a dissatisfied patient if the patient's expectations were not managed preoperatively. Development of reasonable expectations is a crucial component of counseling, and it is the responsibility of both the patient and the surgeon to engage on the topic and come to an agreement before surgery. Postoperatively, maintaining those expectations is a team effort, shared by the patient, the surgeon, and the clinic nurse.

During surgery and in the initial postoperative period, effective communication among the surgeon, anesthesia provider, and nursing staff is crucial for optimizing outcomes and preventing complications. Although fastidious surgical technique and meticulous hemostasis go a long way toward avoiding scarring, asymmetry, nerve injury, and bleeding, maintenance of a low systolic blood pressure and prophylactic treatment for pain and nausea by the anesthesia and recovery room nursing staff have been shown to be the most important interventions in the prevention of hematomas.[23][24]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Fascial Planes of the Face. This illustration depicts the fascial planes of the face, highlighting the continuity of the frontalis muscle, galea aponeurotica, temporoparietal fascia, superficial musculoaponeurotic system, platysma, and the location of the facial nerve.

Contributed by K Humphreys and MH Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Upper Neck Hematoma. An upper neck hematoma is centered just posterior to the angle of the mandible, on postoperative day 1 following rhytidectomy in a 60-year-old male with hypertension. This location is a common site for post-rhytidectomy hematoma, although the size of this hematoma is significantly larger than typically observed.

Contributed by MH Hohman, MD, FACS

References

Bater KL, Ishii LE, Papel ID, Kontis TC, Byrne PJ, Boahene KDO, Nellis JC, Ishii M. Association Between Facial Rejuvenation and Observer Ratings of Youth, Attractiveness, Success, and Health. JAMA facial plastic surgery. 2017 Sep 1:19(5):360-367. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2017.0126. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28448667]

Locher WG, Feinendegen DL. [The early days of aesthetic surgery: facelift pioneers Eugen Holländer (1867-1932) and Erich Lexer (1967-1937)]. Handchirurgie, Mikrochirurgie, plastische Chirurgie : Organ der Deutschsprachigen Arbeitsgemeinschaft fur Handchirurgie : Organ der Deutschsprachigen Arbeitsgemeinschaft fur Mikrochirurgie der Peripheren Nerven und Gefasse : Organ der V.... 2020 Dec:52(6):545-551. doi: 10.1055/a-1150-7343. Epub 2020 May 14 [PubMed PMID: 32408370]

Yang AJ, Hohman MH. Rhytidectomy. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 33232008]

Hamra ST. Composite rhytidectomy and the nasolabial fold. Clinics in plastic surgery. 1995 Apr:22(2):313-24 [PubMed PMID: 7634740]

Tonnard P,Verpaele A, The MACS-lift short scar rhytidectomy. Aesthetic surgery journal. 2007 Mar-Apr; [PubMed PMID: 19341646]

Quatela V, Montague A, Manning JP, Antunes M. Extended Superficial Musculoaponeurotic System Flap Rhytidectomy. Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 2020 Aug:28(3):303-310. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2020.03.007. Epub 2020 May 6 [PubMed PMID: 32503716]

Charafeddine AH, Zins JE. The Extended Superficial Musculoaponeurotic System. Clinics in plastic surgery. 2019 Oct:46(4):533-546. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2019.05.002. Epub 2019 Jul 18 [PubMed PMID: 31514806]

Sykes JM, Riedler KL, Cotofana S, Palhazi P. Superficial and Deep Facial Anatomy and Its Implications for Rhytidectomy. Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 2020 Aug:28(3):243-251. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2020.03.005. Epub 2020 May 6 [PubMed PMID: 32503712]

Damitz LA. The Utility of Superficial Musculoaponeurotic System Flaps in Facelift Procedures. Annals of plastic surgery. 2018 Jun:80(6S Suppl 6):S406-S409. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000001344. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29668506]

Hohman MH, Bhama PK, Hadlock TA. Epidemiology of iatrogenic facial nerve injury: a decade of experience. The Laryngoscope. 2014 Jan:124(1):260-5. doi: 10.1002/lary.24117. Epub 2013 Apr 18 [PubMed PMID: 23606475]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePitanguy I, Ramos AS. The frontal branch of the facial nerve: the importance of its variations in face lifting. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1966 Oct:38(4):352-6 [PubMed PMID: 5926990]

DINGMAN RO, GRABB WC. Surgical anatomy of the mandibular ramus of the facial nerve based on the dissection of 100 facial halves. Plastic and reconstructive surgery and the transplantation bulletin. 1962 Mar:29():266-72 [PubMed PMID: 13886490]

McKinney P, Katrana DJ. Prevention of injury to the great auricular nerve during rhytidectomy. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1980 Nov:66(5):675-9 [PubMed PMID: 7433552]

Pérez P, Hohman MH. Neck Rejuvenation. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32965900]

Rees TD,Liverett DM,Guy CL, The effect of cigarette smoking on skin-flap survival in the face lift patient. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1984 Jun; [PubMed PMID: 6728942]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBassiri-Tehrani B, Abi-Rafeh J, Baker NF, Kerendi AN, Nahai F. Systolic Blood Pressure Less Than 120 mmHg is a Safe and Effective Method to Minimize Bleeding After Facelift Surgery: A Review of 502 Consecutive Cases. Aesthetic surgery journal. 2023 Nov 16:43(12):1420-1428. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjad228. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37439229]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHönig JF. [Concepts in face lifts. State of the art]. Mund-, Kiefer- und Gesichtschirurgie : MKG. 1997 May:1 Suppl 1():S21-6 [PubMed PMID: 9424371]

Adamson PA, Chen T. The dangerous dozen--avoiding potential problem patients in cosmetic surgery. Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 2008 May:16(2):195-202, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2007.11.010. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18355705]

Trimas GE, Frost MDT, Trimas SJ. Tranexamic Acid in Tumescence for Cervicofacial Rhytidectomies. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. Global open. 2024 Jan:12(1):e5540. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000005540. Epub 2024 Jan 23 [PubMed PMID: 38264441]

Roskies M, Bray D, Gordon NA, Gualdi A, Nayak LM, Talei B. Limited Delamination Modifications to the Extended Deep Plane Rhytidectomy: An Anatomical Basis for Improved Outcomes. Facial plastic surgery & aesthetic medicine. 2024 Nov-Dec:26(6):657-664. doi: 10.1089/fpsam.2024.0018. Epub 2024 Jul 29 [PubMed PMID: 39072376]

Hamra ST. The deep-plane rhytidectomy. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1990 Jul:86(1):53-61; discussion 62-3 [PubMed PMID: 2359803]

Gordon NA, Adam SI 3rd. Deep plane face lifting for midface rejuvenation. Clinics in plastic surgery. 2015 Jan:42(1):129-42. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2014.08.009. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25440750]

Stewart CM, Bassiri-Tehrani B, Jones HE, Nahai F. Evidence of Hematoma Prevention After Facelift. Aesthetic surgery journal. 2024 Jan 16:44(2):134-143. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjad247. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37540899]

Beer GM, Goldscheider E, Weber A, Lehmann K. Prevention of acute hematoma after face-lifts. Aesthetic plastic surgery. 2010 Aug:34(4):502-7. doi: 10.1007/s00266-010-9488-8. Epub 2010 Mar 24 [PubMed PMID: 20333520]