Introduction

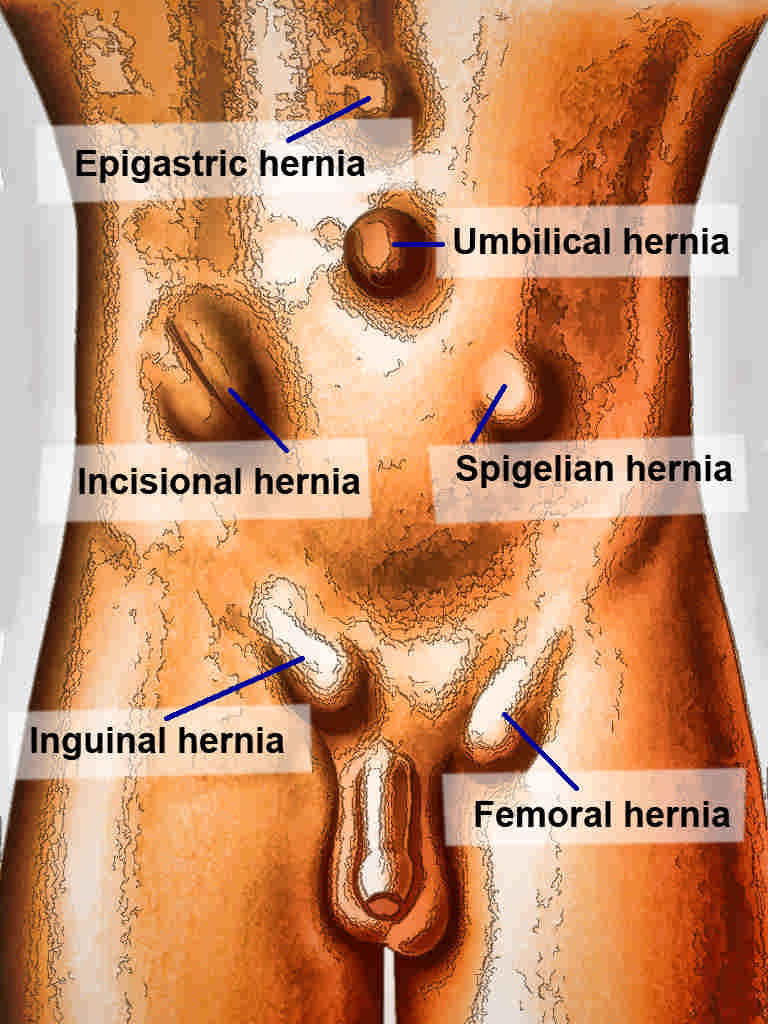

A hernia is defined as an abnormal protrusion of an organ or tissue through a defect in its surrounding walls. Hernia defects may occur in various locations of the abdominal wall, but most commonly occur in the inguinal region (see Image. Abdominal Hernias). Hernias can occur at sites where the aponeurosis and fascia are not covered by striated muscle. As a result, the peritoneal membrane or hernia sac may protrude from the orifice or neck of a hernia.

A femoral hernia occurs in the femoral canal and is bordered by the inguinal ligament anterosuperiorly, Cooper's ligament inferiorly, the femoral vein laterally, and the junction of the iliopubic tract and Cooper's ligament (lacunar ligament) medially. A femoral hernia typically presents with a characteristic bulge below the inguinal ligament. Strangulation is the most common serious complication of a femoral hernia; these hernias have the highest rate of strangulation (15% to 20%).

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Generally, most hernias result from activities that cause increased intra-abdominal pressure. While inguinal hernias occur 9 to 12 times more commonly in males, femoral hernias are 4 times more likely in females.[1]

Femoral Hernia Risk Factors

Risk factors that increase the likelihood of the development of a femoral hernia include:

- Advanced age

- Obesity

- Smoking

- Pregnancy

- Connective tissue disorders [1]

Epidemiology

The lifetime occurrence of a groin hernia is 27% to 43% in men and 3% to 6% in women.[1] Femoral hernias occur less commonly than inguinal hernias and typically account for about 3% of all groin hernias. While inguinal hernias are still most common regardless of gender, femoral hernias are much more common in females. Other coexisting defects may be present at the time of diagnosis, as 10% of women and 50% of men with a femoral hernia either have or will develop an inguinal hernia. The prevalence of a femoral hernia increases with age, as does the risk of complications, including incarceration or strangulation.[1]

Both femoral and inguinal hernias most frequently occur on the right side. This is likely due to a developmental delay in closure of the processus vaginalis after the normal slower descent of the right testis during fetal development.

Pathophysiology

Femoral hernias occur due to weakness or widening of the femoral ring, which is medial to the femoral vein. Widening or weakness of the femoral ring allows abdominal viscera to herniate through it, causing the characteristic bulge below the inguinal ligament. The hernia sac will typically contain small bowel or omentum.

History and Physical

Clinical Features of Femoral Hernias

Clinically, femoral hernias may present as a bulge or painful mass in the groin, often below the inguinal ligament that worsens with standing, straining, lifting, or coughing. Patients may describe groin pain as an ache or a pulling or burning sensation.[2] However, approximately one-third of patients may be asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis, and a femoral hernia may be detected during a routine physical examination.[3] Typically, a slight bulge is noted below the level of the inguinal ligament. On occasion, the bulge may ascend cephalad, suggesting a more commonly noted inguinal hernia. Herniated preperitoneal fat is frequently noted within the hernia sac and may be reduced with direct pressure or manipulation. Incarceration refers to content that cannot be reduced from within the hernia sac or defect.

Hernia Strangulation Clinical Features

Strangulation is a common complication of femoral hernias, and patients with this condition may present urgently for evaluation. Strangulation refers to a vascular compromise of the contents of a hernia. This occurs more frequently in the setting of a hernia with a narrow neck, resulting in obstruction of arterial flow and venous drainage to the contents of the hernia. As a result, there may be engorgement of the hernia sac and contents, with findings on exam of a painful, hard lump or mass. If the small or large intestine is contained within the hernia sac, a patient may present with signs or symptoms of obstruction, including nausea, vomiting, abdominal distention, abdominal pain, and obstipation. Patients may also present with paresthesias related to compression of nearby sensory nerves.

Evaluation

A clinician should have a high index of suspicion of a femoral hernia when evaluating a patient with a bulge or painful mass in the groin region. A physical exam should be performed in both the supine and standing positions, if possible. Visual inspection for asymmetry, bulges, or masses should be performed. Palpation for an inguinal defect is often done by placing a fingertip along the invaginated scrotal wall to evaluate the inguinal canal and inguinal floor. The Valsalva maneuver may be helpful to distinguish between soft tissue masses and hernias. Classically, a bulge identified below the inguinal ligament is consistent with a femoral hernia.

A careful reduction may be attempted in an otherwise asymptomatic patient, but caution should be taken to avoid manual reduction if there is pain or signs of strangulation or obstruction. An incarcerated femoral hernia is more likely to progress to strangulation the longer surgery is delayed from symptom onset, so surgical consultation should be sought emergently in any patient who presents with pain or obstructive symptoms associated with a groin bulge.[4]

Imaging studies, including ultrasound or computed tomography (CT), can be utilized in the evaluation of a groin bulge. Both studies demonstrate a high degree of both sensitivity and specificity in detecting femoral and inguinal hernias. This may allow better evaluation in morbidly obese patients in whom detection may be more challenging on physical exam alone.[5] CT provides better visualization in patients who may present with incarceration or strangulation on exam. Currently, laparoscopy is not generally considered part of the diagnostic process for groin complaints and bulges. However, laparoscopic repair of groin hernias has led to increased intraoperative diagnoses of femoral hernias.[1][6][7]

Treatment / Management

Surgical Management of Femoral Hernias

Surgical intervention remains the only cure. Experts often recommend that femoral hernias be repaired at the time of diagnosis due to their increased incidence of complications, including incarceration or strangulation, compared to the more common inguinal hernia.[1] Concerning the timing of intervention, the finding of strangulation or obstruction presents a surgical emergency, and operative intervention should not be delayed.

Femoral hernias may be repaired using a standard inguinal approach, an open preperitoneal approach, or a minimally invasive (laparoscopic or robotic-assisted laparoscopic) approach. Regardless of the technique or approach, key steps in repairing a femoral hernia include dissection and reduction of the hernia sac, followed by closure of the defect or obliteration of the defect with the placement of a prosthetic mesh.

If a clinical concern for incarceration or strangulation is present, the hernia sac should be opened, and the contents should be examined to assess viability. The lacunar ligament may be divided, if necessary, to facilitate reduction of the hernia sac and its contents. Placement of prosthetic mesh should be avoided in the setting of compromised bowel, enterotomy, or gross contamination due to concerns of infection or bacterial exposure within the operative field. Mesh infection, although uncommon, is a serious complication that can be difficult to treat and often requires explantation of the infected prosthesis. Surgical site infection is estimated to be 2% to 4% for elective inguinal or femoral hernia repairs.[8][9](A1)

Hernia recurrence rates

Many repair methods are available, suggesting that no single preferred repair method exists.[10] Additionally, significant variations in surgical techniques utilized for repair result from cultural differences among surgeons, different reimbursement systems, and differences in resources and logistical capabilities.[1] The recurrence rate after open repair is approximately 4%, but the rates of recurrence in nonmesh repairs and emergency repairs are slightly higher. The elective repair recurrence rate is <1%.[11] (A1)

Minimally invasive techniques

As minimally invasive techniques have evolved, some centers have started using laparoscopic or robotic repairs for emergency operations. Evidence to suggest that laparoscopic management is unsafe has not been documented, and it has been found to have equivalent outcomes to open repair in the emergency setting.[12] Minimally invasive approaches also lead to higher intraoperative diagnosis rates of femoral hernias, though the clinical significance of these intraoperative findings has not yet been adequately studied.[6] Because females have a higher incidence of femoral hernias as well as concurrent inguinal hernia, some studies suggest that females should undergo laparoscopic surgery for any diagnosed groin hernia.[7](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of a groin mass is broad, including an inguinal hernia, hydrocele or varicocele, lymphadenopathy, lipoma, cyst, abscess, hematoma, and femoral artery pseudoaneurysm/aneurysm. Clinical history and physical exam findings are essential factors in determining an accurate diagnosis.[2] Evaluation of the contralateral groin for asymmetry, as well as the external genitalia, extremities, and abdomen, is necessary to help establish a diagnosis. Imaging studies, eg, ultrasonography or CT, although costly, can also be useful in the diagnostic workup of an uncharacterized groin mass.

Prognosis

In most cases, the success of femoral hernia repair is excellent. Overall recurrence rates for groin hernias range between 1% and 10%. Tension-free techniques and mesh-based repairs, if appropriate, result in approximately a 60% reduction in ipsilateral recurrence compared to nonmesh or suture-based repairs.

Complications

Risk factors for femoral hernia recurrence include tobacco abuse, obesity, increased intra-abdominal pressure, coexisting infection, collagen tissue disorders, diabetes, and poor nutritional state. Most hernias recur within the first 2 years after repair. Risks and benefits discussion with patients preoperatively should include the possibility of chronic pain following herniorrhaphy.

Chronic pain may occur in up to 15% of patients following hernia repair and can affect activities of daily living in a small subset of patients.[13] In many cases, post-herniorrhaphy pain can be managed nonoperatively with anti-inflammatory medications or analgesics. Other postoperative complications may include urinary retention, surgical site infection, seroma, or orchitis.[14]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Most patients with a femoral hernia undergo elective repair in an outpatient setting. Surgery may be performed under general or regional anesthesia (spinal) in most situations.[15] Patients are typically advised to refrain from heavy lifting or straining and may have restrictions placed on their physical activities during the early postoperative period. The timing of return to usual activities varies depending on numerous patient factors and surgeon preferences. The hospital length of stay is longer for patients undergoing emergency repair.

Consultations

When identified on routine physical examination, patients with a femoral hernia should be referred to general surgery for consideration of elective femoral hernia repair, even if asymptomatic, due to the higher risk of complications, including incarceration or strangulation, with femoral hernias. In patients who present urgently with an acute onset of pain or a bulge in the femoral region or with signs or symptoms of obstruction or strangulation, an urgent evaluation must occur with timely consultation and surgical evaluation for repair.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be informed when a femoral hernia is identified or suspected during a physical examination or imaging. Educating the patient on the signs and symptoms of incarceration, strangulation, and obstruction that should prompt urgent or emergent evaluation is essential. Once surgical management is deemed necessary, patients must be fully informed of the nature of the operation, the associated operative risks, and the possibility of future reoperation.

Pearls and Other Issues

The following factors should be kept in mind when evaluating and managing femoral hernias:

- Femoral hernias typically present with a mass or bulge below the level of the inguinal ligament. Femoral hernias occur most commonly in women but have a lower incidence than inguinal hernias.

- Incarceration or strangulation is common with a femoral hernia due to the small size of the hernia neck.

- All patients with a femoral hernia should be considered for repair due to the high risk of complications associated with femoral hernias.

- Surgical techniques for repair include open (standard Cooper’s ligament repair, preperitoneal approach) and minimally invasive (standard laparoscopic or robotic-assisted laparoscopic) techniques. Patient factors, surgeon preference, and technical proficiency should all be considered when selecting the repair method.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective management of femoral hernias requires a coordinated, interprofessional approach focused on timely diagnosis, patient safety, and optimal outcomes. Physicians and advanced practitioners play a central role in the early identification of groin masses and must maintain a high index of suspicion for femoral hernias due to their high risk of complications such as strangulation. Prompt surgical consultation is essential upon diagnosis. General surgeons lead operative planning, while internists, cardiologists, and pulmonologists are instrumental in preoperative optimization, particularly in patients with complex comorbidities. Anesthesiologists ensure perioperative stability, while perioperative nurses support both patient preparation and immediate postoperative care. Each team member must clearly understand their responsibilities to ensure seamless transitions throughout the care continuum.

Pharmacists contribute by managing perioperative medication regimens, including anticoagulants, antibiotics, and pain control, helping prevent complications and supporting rapid recovery. Nurses play a key role in patient education, wound care, and promoting early mobilization, which has been shown to reduce postoperative complications and hospital stay. Interprofessional communication is vital throughout this process, with regular updates and collaborative planning ensuring that all aspects of the patient's needs are addressed. The use of standardized, patient-centered care pathways further enhances coordination, improves efficiency, and supports safer, higher-quality outcomes for patients undergoing femoral hernia repair.

Media

References

HerniaSurge Group. International guidelines for groin hernia management. Hernia : the journal of hernias and abdominal wall surgery. 2018 Feb:22(1):1-165. doi: 10.1007/s10029-017-1668-x. Epub 2018 Jan 12 [PubMed PMID: 29330835]

Shakil A, Aparicio K, Barta E, Munez K. Inguinal Hernias: Diagnosis and Management. American family physician. 2020 Oct 15:102(8):487-492 [PubMed PMID: 33064426]

Halgas B, Viera J, Dilday J, Bader J, Holt D. Femoral Hernias: Analysis of Preoperative Risk Factors and 30-Day Outcomes of Initial Groin Hernias Using ACS-NSQIP. The American surgeon. 2018 Sep 1:84(9):1455-1461 [PubMed PMID: 30268175]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBeji H, Bouassida M, Chtourou MF, Zribi S, Laamiri G, Kallel Y, Mroua B, Mighri MM, Touinsi H. Predictive factors of bowel necrosis in patients with incarcerated femoral hernia. Hernia : the journal of hernias and abdominal wall surgery. 2023 Dec:27(6):1491-1496. doi: 10.1007/s10029-023-02776-1. Epub 2023 Mar 21 [PubMed PMID: 36943519]

Niebuhr H, König A, Pawlak M, Sailer M, Köckerling F, Reinpold W. Groin hernia diagnostics: dynamic inguinal ultrasound (DIUS). Langenbeck's archives of surgery. 2017 Nov:402(7):1039-1045. doi: 10.1007/s00423-017-1604-7. Epub 2017 Aug 15 [PubMed PMID: 28812139]

Maskal SM, Ellis RC, Melland-Smith M, Messer N, Phillips S, Miller BT, Beffa LRA, Petro CC, Rosen MJ, Prabhu AS. Revisiting femoral hernia diagnosis rates by patient sex in inguinal hernia repairs. American journal of surgery. 2024 Apr:230():21-25. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2023.10.048. Epub 2023 Oct 26 [PubMed PMID: 37914661]

Rasador ACD, da Silveira CAB, Lech GE, de Lima BV, Lima DL, Malcher F. The missed diagnosis of femoral hernias in females undergoing inguinal hernia repair - A systematic review and proportional meta-analysis. Hernia : the journal of hernias and abdominal wall surgery. 2024 Nov 16:29(1):17. doi: 10.1007/s10029-024-03196-5. Epub 2024 Nov 16 [PubMed PMID: 39549170]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceErdas E, Medas F, Pisano G, Nicolosi A, Calò PG. Antibiotic prophylaxis for open mesh repair of groin hernia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Hernia : the journal of hernias and abdominal wall surgery. 2016 Dec:20(6):765-776. doi: 10.1007/s10029-016-1536-0. Epub 2016 Sep 3 [PubMed PMID: 27591996]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBoonchan T, Wilasrusmee C, McEvoy M, Attia J, Thakkinstian A. Network meta-analysis of antibiotic prophylaxis for prevention of surgical-site infection after groin hernia surgery. The British journal of surgery. 2017 Jan:104(2):e106-e117. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10441. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28121028]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKöckerling F, Simons MP. Current Concepts of Inguinal Hernia Repair. Visceral medicine. 2018 Apr:34(2):145-150. doi: 10.1159/000487278. Epub 2018 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 29888245]

Romano L, Fiasca F, Mattei A, Di Donato G, Venturoni A, Schietroma M, Giuliani A. Recurrence Rates after Primary Femoral Hernia Open Repair a Systematic Review. Surgical innovation. 2024 Oct:31(5):555-562. doi: 10.1177/15533506241273398. Epub 2024 Aug 3 [PubMed PMID: 39096064]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceShuttleworth P, Sabri S, Mihailescu A. The Utility of Minimally Invasive Surgery in the Emergency Management of Femoral Hernias: A Systematic Review. Journal of abdominal wall surgery : JAWS. 2023:2():11217. doi: 10.3389/jaws.2023.11217. Epub 2023 Apr 21 [PubMed PMID: 38312401]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLundström KJ, Holmberg H, Montgomery A, Nordin P. Patient-reported rates of chronic pain and recurrence after groin hernia repair. The British journal of surgery. 2018 Jan:105(1):106-112. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10652. Epub 2017 Nov 15 [PubMed PMID: 29139566]

Lockhart K, Dunn D, Teo S, Ng JY, Dhillon M, Teo E, van Driel ML. Mesh versus non-mesh for inguinal and femoral hernia repair. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2018 Sep 13:9(9):CD011517. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011517.pub2. Epub 2018 Sep 13 [PubMed PMID: 30209805]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSunamak O, Donmez T, Yildirim D, Hut A, Erdem VM, Erdem DA, Ozata IH, Cakir M, Uzman S. Open mesh and laparoscopic total extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair under spinal and general anesthesia. Therapeutics and clinical risk management. 2018:14():1839-1845. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S175314. Epub 2018 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 30319265]