Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common, chronic disorder of gut-brain interaction characterized by recurrent abdominal pain and altered bowel habits, including constipation, diarrhea, or both. Despite its high prevalence and significant impact on quality of life, IBS often remains underdiagnosed or mismanaged, leading to excessive diagnostic testing, unnecessary specialty referrals, and increased healthcare costs.[1] The pathophysiology of IBS is multifactorial, involving disruptions in the gut-brain axis, visceral hypersensitivity, gastrointestinal dysmotility, alterations in gut microbiota, food intolerances, and psychosocial factors.

Accurate diagnosis using the Rome IV criteria and a targeted evaluation strategy is essential for identifying IBS and ruling out conditions with overlapping symptoms. Abdominal pain in IBS is often related to defecation and can vary in location, character, and severity. Disordered defecation in IBS can present as constipation, diarrhea, or alternating bowel habits. Bloating is a commonly associated symptom, but is not required for the diagnosis of IBS.[2] A positive diagnostic approach, rather than a diagnosis of exclusion, allows for earlier intervention and improved patient outcomes.

Management of IBS involves lifestyle and dietary modifications, pharmacologic treatment options tailored to IBS subtypes, and the integration of psychological interventions when indicated. Additionally, a strong patient-clinician relationship is crucial in fostering trust, enhancing symptom management, and promoting adherence to treatment plans to deliver timely, cost-effective, and patient-centered care to individuals living with IBS.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

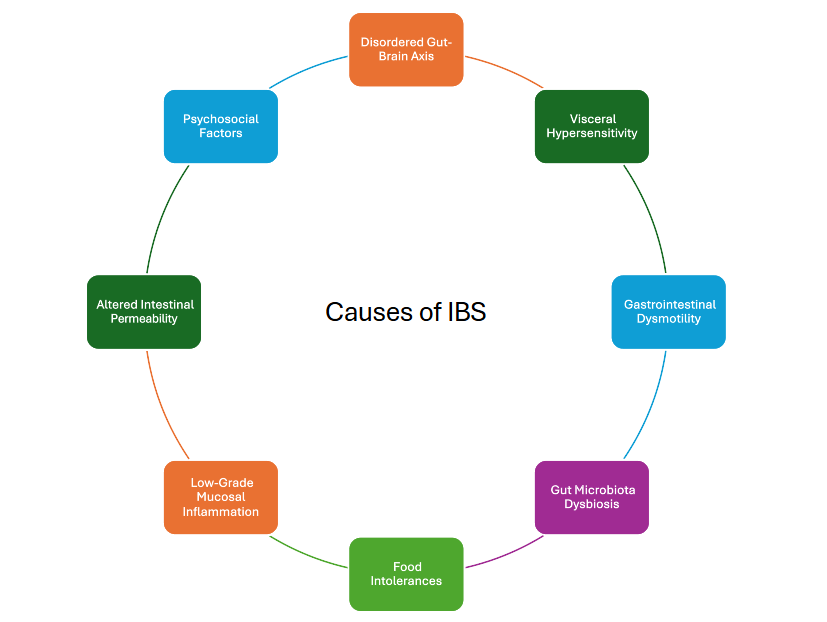

The exact cause of IBS remains unknown; however, the following factors have been identified as contributing to its pathophysiology (see Image. Causes of Irritable Bowel Syndrome):

- Disordered gut-brain axis: Disorders of gut-brain interaction (DGBIs) primarily involve disruption of the gut-brain axis, which relies on complex signaling between the central (CNS) and enteric nervous systems (ENS) via neuronal, endocrine, immune, and metabolic pathways and is influenced by several factors, eg, genetics, diet, stress, and social factors.[3][4]

- Visceral hypersensitivity: Patients with IBS often exhibit heightened visceral sensitivity due to increased signaling from intestinal receptors to the central nervous system (CNS) in response to stimuli, eg, gas distension.[5][6]

- Gastrointestinal dysmotility: Patients with IBS may exhibit irregular contractions or transit delays, as seen in IBS with predominant constipation (IBS-C), or exaggerated motility, as seen in IBS with predominant diarrhea (IBS-D).

- Gut microbiota dysbiosis: Distinct alterations in microbiota have been linked to IBS subtypes.[7][8]

- Food intolerances: Food intolerances have been reported in 20% to 65% of patients with IBS; however, objective evidence to suggest causation is often lacking, and various other factors may contribute.[9]

- Low-grade mucosal inflammation: Lymphocyte infiltration and eosinophilia are commonly observed on histological examination, particularly in postinfectious and diarrhea-predominant cases.[10][11]

- Altered intestinal permeability: Increased intestinal permeability, particularly in IBS-D, has been linked to diet, microbiome shifts, and mediators such as serotonin and proteases.[12]

- Psychosocial factors: Psychological factors, eg, stress, can impact intestinal sensitivity, motility, and microbiota, thereby worsening IBS symptoms.[13]

Epidemiology

In the United States, the prevalence of IBS ranges from 7% to 16%.[14] An international meta-analysis estimated a pooled global prevalence of 11%, though significant variation exists depending on geographic region.[15] Socioeconomic status does not consistently correlate with the occurrence of IBS, although familial aggregation has been observed, indicating potential contributions from both genetic predisposition and sociocultural factors. IBS tends to be diagnosed more frequently in women within Western populations.[16] The condition occurs more commonly in younger adults, with a noticeable decline in prevalence after the age of 50.[17]

History and Physical

Conducting a thorough history remains essential for identifying patients who meet the Rome IV criteria for IBS. Detailed history-taking helps determine the specific IBS subtype, differentiate IBS from other conditions with overlapping symptoms, and assess for the presence of alarm features that may indicate underlying organic disease. Physical examination is typically normal in patients with IBS; however, some patients may experience tenderness upon palpation.

According to the Rome IV criteria, a diagnosis of IBS requires recurrent abdominal pain occurring, on average, at least 1 day per week over the past 3 months. This pain must be associated with at least 2 of the following: defecation, a change in stool frequency, or a change in stool form (appearance). These criteria must have been fulfilled within the last 3 months, with symptom onset occurring at least 6 months before diagnosis. This structured approach supports timely and accurate diagnosis, allowing for appropriate management and minimizing unnecessary investigations.[18]

Diagnostic Criteria for Irritable Bowel Syndrome Subtypes

The following IBS subtypes are classified by predominant bowel habits based on stool form on days with at least 1 abnormal bowel movement:

- IBS with predominant constipation (IBS-C): >25% of bowel movements with Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS) types 1 or 2 and <25% with BSFS types 6 or 7

- IBS with predominant diarrhea (IBS-D): >25% of bowel movements with BSFS types 6 or 7 and <25% with BSFS types 1 or 2

- IBS with mixed bowel habits (IBS-M): >25% of bowel movements with BSFS types 1 or 2 and >25% with BSFS types 6 or 7

- IBS Unclassified (IBS-U): an unclassified subcategory that meets the criteria for IBS, but bowel movements cannot accurately be categorized into 1 of the 3 subgroups

Differentiating IBS from other gastrointestinal conditions that mimic IBS symptoms, eg, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and celiac disease, is essential in patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS. Similarly, in patients with constipation-predominant IBS, a history of straining during stool passage and the need for manual disimpaction could suggest a rectal evacuation disorder. In patients with abdominal pain and diarrhea, other gastrointestinal disorders with overlapping symptoms should be excluded, eg, IBD and celiac disease. Likewise, in those with abdominal pain and constipation, symptoms like excessive straining or the need for manual disimpaction to pass stool may point towards pelvic floor dysfunction.

Red Flag Clinical Features

The presence of red flags or alarm symptoms in the patient's history should raise suspicion of an underlying organic disorder that warrants further diagnostic evaluation, including:

- New symptom onset at the age of 50 or older

- Blood in the stools (red blood or black, tarry stool)

- Fever, shaking chills, or night sweats

- Nocturnal diarrhea

- Unintentional weight loss

- Change in your typical IBS symptoms (eg, new and different pain)

- Recent use of antibiotics

- Laboratory abnormalities (eg, iron deficiency anemia, elevated C-reactive protein or fecal calprotectin)

- Family history of other gastrointestinal diseases, eg, cancer, IBD, or celiac disease

Evaluation

Current guidelines recommend a limited diagnostic evaluation to rule out other disorders that present with symptoms similar to those of IBS. This approach helps avoid unnecessary testing and supports the timely initiation of appropriate therapy.[19]

For patients with IBS-D, recommended testing includes celiac serologies, fecal calprotectin or lactoferrin, and C-reactive protein (CRP) to exclude IBD. Additional testing for bile acid diarrhea may be appropriate when clinically suspected. In regions where Giardia is endemic, a Giardia stool antigen test is also advised. Routine testing for food allergies or sensitivities, general stool analyses, or hydrogen breath testing for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) should be reserved for cases where clinical suspicion specifically supports those diagnoses.

In patients with IBS-C, recommended evaluations include celiac serologies and anorectal physiology testing to assess for pelvic floor dysfunction. In the absence of alarm symptoms, routine colonoscopy is not advised for patients younger than 45 years.

Adopting a positive diagnostic strategy—focused on confirming IBS rather than excluding other conditions—enhances cost-effectiveness and enables prompt initiation of targeted treatment.[19] This method reinforces the importance of clinical criteria in guiding both diagnosis and management.

Treatment / Management

The treatment involves a multifactorial approach that integrates dietary changes, lifestyle modifications, pharmacologic therapy, and psychological interventions. Each component targets different aspects of the disorder’s pathophysiology and symptomatology, with individualized treatment plans tailored to the IBS subtype and patient preferences.

Patient-Clinician Alliance

A strong patient-clinician relationship and shared decision-making form the foundation of effective care for individuals with IBS. This therapeutic alliance enhances motivation, interpersonal support, and the patient’s expectation of symptom improvement.[20] Trust, mutual goal setting, patient education, reassurance, and the consideration of psychological factors all contribute to a successful partnership. Establishing this connection enables patients to actively engage in their care and adhere to treatment recommendations more consistently.(B2)

Lifestyle Modifications

Lifestyle modifications can improve overall IBS symptom control. Regular physical activity and improved sleep hygiene have been shown to have benefits in some studies, particularly in reducing global symptoms, eg, abdominal pain, cramping, and bloating. These simple, nonpharmacologic strategies often serve as first-line interventions and support long-term well-being.[21][22](A1)

Dietary Modifications

Dietary interventions play a central role in IBS management, as many patients report symptom exacerbation following certain foods. Referral to a registered dietitian nutritionist remains essential for patients willing to modify their diet. The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) identifies the low-FODMAP (fermentable oligo-, di-, and monosaccharides and polyols) diet as the most evidence-based dietary intervention for IBS. This approach consists of the following 3 phases:

- A 4- to 6-week restriction period, systematic

- Reintroduction of FODMAP foods

- Individualized personalization based on symptom response [23]

The AGA and American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) also strongly support the use of soluble fiber for improving global IBS symptoms.[19][23][24] While other diets, eg, the gluten-free diet (GFD), have shown promise in observational studies, randomized controlled trials have not confirmed their efficacy. Long-term restrictive diets that lack clinical benefit should be discontinued due to the potential for nutritional deficiencies.[23] If dietary and lifestyle modifications fail to control symptoms adequately, pharmacologic therapy should be initiated based on IBS subtype and symptom severity (eg, abdominal pain).(A1)

Constipation-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome Management

In IBS-C, the AGA recommends osmotic laxatives, eg, polyethylene glycol (PEG) as first-line treatment.[25] Although PEG effectively relieves constipation, it offers limited benefit for bloating or abdominal pain. Second-line agents include secretagogues (eg, linaclotide, lubiprostone, and tenapanor), which enhance intestinal secretion and motility. Tegaserod, a 5-HT4 receptor agonist, serves as a third-line option approved for use in women younger than 65 who have no history of cardiovascular ischemic events.

Diarrhea-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome Management

For IBS-D, first-line therapies include loperamide, a synthetic μ-opioid receptor agonist, and bile acid sequestrants, which may benefit patients with bile acid malabsorption, a condition present in up to 50% of those with IBS-D.[26] Several second-line treatment options are available. Rifaximin, a nonabsorbable antibiotic, is recommended by both AGA and ACG for moderate to severe IBS-D and may be used for retreatment in cases of symptom relapse.[27] (A1)

Additional gut-specific pharmacotherapy options include eluxadoline, a mixed μ- and kappa-opioid receptor (KOR) agonist, which is contraindicated in patients with gallbladder disease or high alcohol intake (>3 alcoholic beverages/day). Alosetron, a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, may be used as a third-line agent in women with severe IBS-D but carries a black box warning for the risk of ischemic colitis.

Treatment of Global Irritable Bowel Syndrome Symptoms

For global IBS symptoms (eg, abdominal pain, cramping, and bloating), antispasmodics, including peppermint oil and anticholinergic medications (eg, hyoscine or dicyclomine), are frequently used in clinical practice.[28][29] These agents reduce smooth muscle contraction and may diminish visceral hypersensitivity.[30] Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), eg, amitriptyline, nortriptyline, imipramine, and desipramine, act as neuromodulators that target norepinephrine and dopamine receptors.[31] Their anticholinergic properties and ability to slow gastric transit also contribute to symptom relief, particularly in patients with IBS-D.(A1)

Gut-Directed Psychotherapy

Gut-directed psychotherapy offers another valuable treatment option, particularly for patients with IBS linked to psychological stress or mood disorders. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and gut-directed hypnotherapy have demonstrated effectiveness in reducing the frequency and severity of symptoms, primarily in patients with mood-directed IBS symptoms. These interventions address the disrupted gut-brain axis believed to underlie IBS. Current guidelines do not recommend selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or fecal microbiota transplants for IBS management, given insufficient evidence supporting their use in this context.[32][33][34](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of IBS is broad. A limited diagnostic evaluation is recommended if the patient meets the criteria for diagnosis of IBS. Depending on the predominant symptoms, several differential diagnoses should be considered, including:

- IBS-D

- Celiac disease

- IBD

- Microscopic colitis

- Bile acid diarrhea

- Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO)

- Chronic infections (eg, giardiasis)

- Food intolerance (lactose, fructose)

- Medications

- Malignancy

- IBS-C

- Slow colonic transit

- Dyssynergic defecation

- Endocrine abnormalities (hypothyroidism, hypercalcemia)

- Medications

- Malignancy

Prognosis

IBS is a chronic condition characterized by recurrent symptoms of varying severity. However, life expectancy in individuals with IBS is comparable to that of the general population. The diagnosis typically remains stable during follow-up. The use of ambulatory health services by IBS patients can be reduced when a positive relationship and strong rapport are established between the patient and clinician.[35]

Complications

IBS generally remains a manageable condition, with complications occurring infrequently. However, certain patients may experience adverse effects related to the condition and its management. Physical complications, eg, hemorrhoids, anal fissures, and fecal impaction may develop, particularly in those with constipation-predominant IBS. Additionally, patients who follow overly restrictive diets in an attempt to control their symptoms face an increased risk of nutritional deficiencies due to inadequate intake of essential nutrients.

Chronic symptoms and lifestyle disruptions associated with IBS often contribute to the development or worsening of mental health issues, including depression, anxiety, and mood disorders. These psychological effects may stem from the persistent discomfort and unpredictability of symptoms. Additionally, IBS can also significantly impair quality of life. Frequent abdominal pain, altered bowel habits, and bloating may interfere with work performance, academic responsibilities, social engagements, and personal relationships. Many patients report sleep disturbances as well, further compounding physical and emotional stress.

Consultations

Patients with IBS benefit from an interprofessional approach involving various clinicians to address the diverse manifestations of the disorder. Primary care clinicians and gastroenterologists typically lead the diagnostic evaluation, applying the Rome IV criteria and determining the appropriate evaluation to rule out other conditions. Referral to a registered dietitian nutritionist can support patients in implementing and personalizing dietary interventions, eg, the low-FODMAP diet, while minimizing the risk of nutritional deficiencies.

Mental health professionals, including psychologists or therapists trained in gut-directed psychotherapy or cognitive behavioral therapy, may be consulted when psychological factors like anxiety or depression contribute to symptom severity. In cases of pelvic floor dysfunction or severe constipation, specialists in colorectal or pelvic floor disorders may conduct anorectal physiology testing and guide treatment. This collaborative care model enhances symptom management, patient education, and long-term outcomes.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Deterrence in IBS focuses on minimizing symptom severity, preventing complications, and avoiding unnecessary diagnostic procedures through early recognition, accurate diagnosis, and evidence-based management. Clinicians can reduce patient reliance on extensive testing and specialty referrals by applying the Rome IV criteria and using a positive diagnostic approach. Educating patients about the chronic but non-life-threatening nature of IBS helps alleviate fears of more serious underlying conditions and fosters a collaborative approach to care. Emphasizing that IBS does not lead to structural damage or cancer also supports patient reassurance and encourages active participation in long-term symptom management.

Effective patient education remains crucial to enhancing outcomes and improving quality of life. Patients should receive clear information about the multifactorial nature of IBS, including the role of diet, stress, gut-brain interactions, and lifestyle factors. Guidance on implementing a low-FODMAP diet, increasing physical activity, and improving sleep hygiene can empower patients to take control of their symptoms and manage them more effectively. Clinicians should also emphasize the importance of psychological well-being and the availability of treatments, eg, gut-directed psychotherapy, when needed. By promoting realistic expectations and offering individualized, evidence-based strategies, education helps patients manage their condition more confidently and reduces the risk of complications related to restrictive diets, unmanaged symptoms, or comorbid mental health concerns.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Providing optimal care for patients with IBS requires a coordinated, interprofessional approach that leverages the unique skills and responsibilities of each healthcare team member. Physicians and advanced practitioners serve as the primary point of contact for diagnosis, applying the Rome IV criteria and performing targeted evaluations to rule out organic conditions. Their responsibility extends to initiating treatment plans, educating patients about the chronic and functional nature of IBS, and fostering trust through shared decision-making. Advanced practitioners, including nurse practitioners and physician assistants, also contribute significantly to ongoing symptom monitoring, reinforcing lifestyle modifications, and adjusting therapeutic interventions based on patient response. Effective interprofessional communication between these clinicians ensures consistent messaging and timely adjustments in care, improving patient safety and outcomes.

Dietitians play a pivotal role in managing IBS symptoms by guiding patients through evidence-based dietary strategies, particularly the low-FODMAP diet, while preventing nutritional deficiencies. Pharmacists contribute their expertise by reviewing medication regimens, managing adverse effects, and ensuring the safe use of agents across IBS subtypes. Behavioral health professionals trained in gut-directed psychotherapy or cognitive behavioral therapy address the psychological components of IBS, helping patients manage stress and emotional triggers that exacerbate symptoms. Nurses support the team by facilitating communication, triaging concerns, and reinforcing education during follow-up. When team members collaborate effectively and communicate clearly, patients receive consistent, coordinated care that prioritizes safety, enhances symptom control, and empowers them to actively participate in their treatment journey. This interprofessional strategy fosters a patient-centered model that improves long-term outcomes and overall quality of care.

Media

References

Shin A, Xu H. Healthcare Costs of Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Irritable Bowel Syndrome Subtypes in the United States. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2024 Aug 1:119(8):1571-1579. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002753. Epub 2024 Mar 14 [PubMed PMID: 38483304]

Mearin F, Lacy BE, Chang L, Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Simren M, Spiller R. Bowel Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016 Feb 18:():. pii: S0016-5085(16)00222-5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.031. Epub 2016 Feb 18 [PubMed PMID: 27144627]

Karakan T, Ozkul C, Küpeli Akkol E, Bilici S, Sobarzo-Sánchez E, Capasso R. Gut-Brain-Microbiota Axis: Antibiotics and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Nutrients. 2021 Jan 27:13(2):. doi: 10.3390/nu13020389. Epub 2021 Jan 27 [PubMed PMID: 33513791]

Rusch JA, Layden BT, Dugas LR. Signalling cognition: the gut microbiota and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Frontiers in endocrinology. 2023:14():1130689. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1130689. Epub 2023 Jun 19 [PubMed PMID: 37404311]

Farzaei MH, Bahramsoltani R, Abdollahi M, Rahimi R. The Role of Visceral Hypersensitivity in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Pharmacological Targets and Novel Treatments. Journal of neurogastroenterology and motility. 2016 Oct 30:22(4):558-574. doi: 10.5056/jnm16001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27431236]

Farmer AD, Aziz Q. Mechanisms and management of functional abdominal pain. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2014 Sep:107(9):347-54. doi: 10.1177/0141076814540880. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25193056]

Wei L, Singh R, Ro S, Ghoshal UC. Gut microbiota dysbiosis in functional gastrointestinal disorders: Underpinning the symptoms and pathophysiology. JGH open : an open access journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 2021 Sep:5(9):976-987. doi: 10.1002/jgh3.12528. Epub 2021 Mar 23 [PubMed PMID: 34584964]

Mancabelli L, Milani C, Lugli GA, Turroni F, Mangifesta M, Viappiani A, Ticinesi A, Nouvenne A, Meschi T, van Sinderen D, Ventura M. Unveiling the gut microbiota composition and functionality associated with constipation through metagenomic analyses. Scientific reports. 2017 Aug 29:7(1):9879. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10663-w. Epub 2017 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 28852182]

Choung RS, Talley NJ. Food Allergy and Intolerance in IBS. Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2006 Oct:2(10):756-760 [PubMed PMID: 28325993]

Singh M, Singh V, Schurman JV, Colombo JM, Friesen CA. The relationship between mucosal inflammatory cells, specific symptoms, and psychological functioning in youth with irritable bowel syndrome. Scientific reports. 2020 Jul 20:10(1):11988. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-68961-9. Epub 2020 Jul 20 [PubMed PMID: 32686762]

Burns GL, Talley NJ, Keely S. Immune responses in the irritable bowel syndromes: time to consider the small intestine. BMC medicine. 2022 Mar 31:20(1):115. doi: 10.1186/s12916-022-02301-8. Epub 2022 Mar 31 [PubMed PMID: 35354471]

Hanning N, Edwinson AL, Ceuleers H, Peters SA, De Man JG, Hassett LC, De Winter BY, Grover M. Intestinal barrier dysfunction in irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review. Therapeutic advances in gastroenterology. 2021:14():1756284821993586. doi: 10.1177/1756284821993586. Epub 2021 Feb 24 [PubMed PMID: 33717210]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceQin HY, Cheng CW, Tang XD, Bian ZX. Impact of psychological stress on irritable bowel syndrome. World journal of gastroenterology. 2014 Oct 21:20(39):14126-31. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i39.14126. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25339801]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSperber AD, Bangdiwala SI, Drossman DA, Ghoshal UC, Simren M, Tack J, Whitehead WE, Dumitrascu DL, Fang X, Fukudo S, Kellow J, Okeke E, Quigley EMM, Schmulson M, Whorwell P, Archampong T, Adibi P, Andresen V, Benninga MA, Bonaz B, Bor S, Fernandez LB, Choi SC, Corazziari ES, Francisconi C, Hani A, Lazebnik L, Lee YY, Mulak A, Rahman MM, Santos J, Setshedi M, Syam AF, Vanner S, Wong RK, Lopez-Colombo A, Costa V, Dickman R, Kanazawa M, Keshteli AH, Khatun R, Maleki I, Poitras P, Pratap N, Stefanyuk O, Thomson S, Zeevenhooven J, Palsson OS. Worldwide Prevalence and Burden of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders, Results of Rome Foundation Global Study. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jan:160(1):99-114.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.014. Epub 2020 Apr 12 [PubMed PMID: 32294476]

Hungin AP, Whorwell PJ, Tack J, Mearin F. The prevalence, patterns and impact of irritable bowel syndrome: an international survey of 40,000 subjects. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2003 Mar 1:17(5):643-50 [PubMed PMID: 12641512]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCanavan C, West J, Card T. The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Clinical epidemiology. 2014:6():71-80. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S40245. Epub 2014 Feb 4 [PubMed PMID: 24523597]

Lovell RM, Ford AC. Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2012 Jul:10(7):712-721.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.02.029. Epub 2012 Mar 15 [PubMed PMID: 22426087]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSchmulson MJ, Drossman DA. What Is New in Rome IV. Journal of neurogastroenterology and motility. 2017 Apr 30:23(2):151-163. doi: 10.5056/jnm16214. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28274109]

Lacy BE, Pimentel M, Brenner DM, Chey WD, Keefer LA, Long MD, Moshiree B. ACG Clinical Guideline: Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2021 Jan 1:116(1):17-44. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001036. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33315591]

Lackner JM, Quigley BM, Radziwon CD, Vargovich AM. IBS Patients' Treatment Expectancy and Motivation Impacts Quality of the Therapeutic Alliance With Provider: Results of the IBS Outcome Study. Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 2021 May-Jun 01:55(5):411-421. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001343. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32301832]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJohannesson E, Simrén M, Strid H, Bajor A, Sadik R. Physical activity improves symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2011 May:106(5):915-22. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.480. Epub 2011 Jan 4 [PubMed PMID: 21206488]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePatel A, Hasak S, Cassell B, Ciorba MA, Vivio EE, Kumar M, Gyawali CP, Sayuk GS. Effects of disturbed sleep on gastrointestinal and somatic pain symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2016 Aug:44(3):246-58. doi: 10.1111/apt.13677. Epub 2016 May 30 [PubMed PMID: 27240555]

Chey WD, Hashash JG, Manning L, Chang L. AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Role of Diet in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2022 May:162(6):1737-1745.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.12.248. Epub 2022 Mar 23 [PubMed PMID: 35337654]

Moayyedi P, Quigley EM, Lacy BE, Lembo AJ, Saito YA, Schiller LR, Soffer EE, Spiegel BM, Ford AC. The effect of fiber supplementation on irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2014 Sep:109(9):1367-74. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.195. Epub 2014 Jul 29 [PubMed PMID: 25070054]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAmerican Gastroenterological Association. Irritable Bowel Syndrome in Adults (IBS-D): Clinical Decision Support Tool. Gastroenterology. 2019 Sep:157(3):855. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.07.008. Epub 2019 Jul 16 [PubMed PMID: 31323183]

Fernández-Bañares F, Esteve M, Salas A, Alsina M, Farré C, González C, Buxeda M, Forné M, Rosinach M, Espinós JC, Maria Viver J. Systematic evaluation of the causes of chronic watery diarrhea with functional characteristics. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2007 Nov:102(11):2520-8 [PubMed PMID: 17680846]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLembo A, Pimentel M, Rao SS, Schoenfeld P, Cash B, Weinstock LB, Paterson C, Bortey E, Forbes WP. Repeat Treatment With Rifaximin Is Safe and Effective in Patients With Diarrhea-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2016 Dec:151(6):1113-1121. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.08.003. Epub 2016 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 27528177]

Ruepert L, Quartero AO, de Wit NJ, van der Heijden GJ, Rubin G, Muris JW. Bulking agents, antispasmodics and antidepressants for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2011 Aug 10:2011(8):CD003460. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003460.pub3. Epub 2011 Aug 10 [PubMed PMID: 21833945]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceIngrosso MR, Ianiro G, Nee J, Lembo AJ, Moayyedi P, Black CJ, Ford AC. Systematic review and meta-analysis: efficacy of peppermint oil in irritable bowel syndrome. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2022 Sep:56(6):932-941. doi: 10.1111/apt.17179. Epub 2022 Aug 9 [PubMed PMID: 35942669]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKhalif IL, Quigley EM, Makarchuk PA, Golovenko OV, Podmarenkova LF, Dzhanayev YA. Interactions between symptoms and motor and visceral sensory responses of irritable bowel syndrome patients to spasmolytics (antispasmodics). Journal of gastrointestinal and liver diseases : JGLD. 2009 Mar:18(1):17-22 [PubMed PMID: 19337628]

Drossman DA, Tack J, Ford AC, Szigethy E, Törnblom H, Van Oudenhove L. Neuromodulators for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction): A Rome Foundation Working Team Report. Gastroenterology. 2018 Mar:154(4):1140-1171.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.11.279. Epub 2017 Dec 22 [PubMed PMID: 29274869]

Goodoory VC, Khasawneh M, Thakur ER, Everitt HA, Gudleski GD, Lackner JM, Moss-Morris R, Simren M, Vasant DH, Moayyedi P, Black CJ, Ford AC. Effect of Brain-Gut Behavioral Treatments on Abdominal Pain in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2024 Oct:167(5):934-943.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2024.05.010. Epub 2024 May 20 [PubMed PMID: 38777133]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLembo A, Sultan S, Chang L, Heidelbaugh JJ, Smalley W, Verne GN. AGA Clinical Practice Guideline on the Pharmacological Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome With Diarrhea. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jul:163(1):137-151. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.04.017. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35738725]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWiedemann HP, Gillis CN. Altered metabolic function of the pulmonary microcirculation. Early detection of lung injury and possible functional significance. Critical care clinics. 1986 Jul:2(3):497-509 [PubMed PMID: 3331559]

Owens DM, Nelson DK, Talley NJ. The irritable bowel syndrome: long-term prognosis and the physician-patient interaction. Annals of internal medicine. 1995 Jan 15:122(2):107-12 [PubMed PMID: 7992984]