Introduction

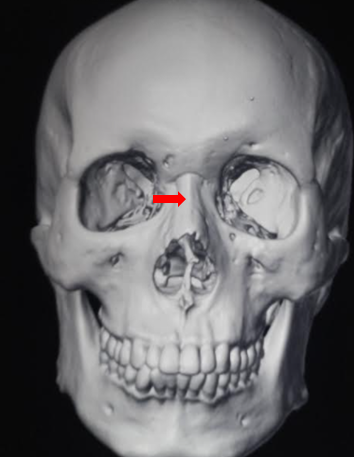

The nasal bones are the most commonly fractured structures in the maxillofacial region, owing to their relative fragility and the prominent position of the nose (see Image. Nasal Bones).[1] Nasal septal fractures are associated with nasal bone fractures in 42% to 96% of cases.[1][2] Nasal bone and septal fractures may affect both the cosmetic appearance and the airway function of the nose.

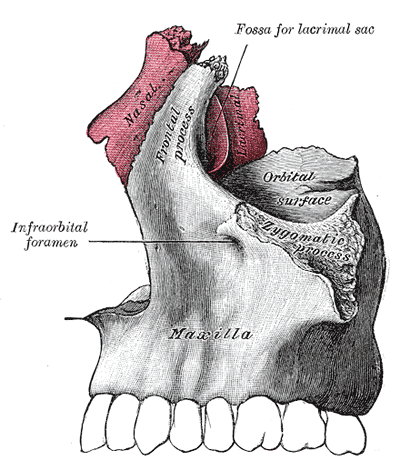

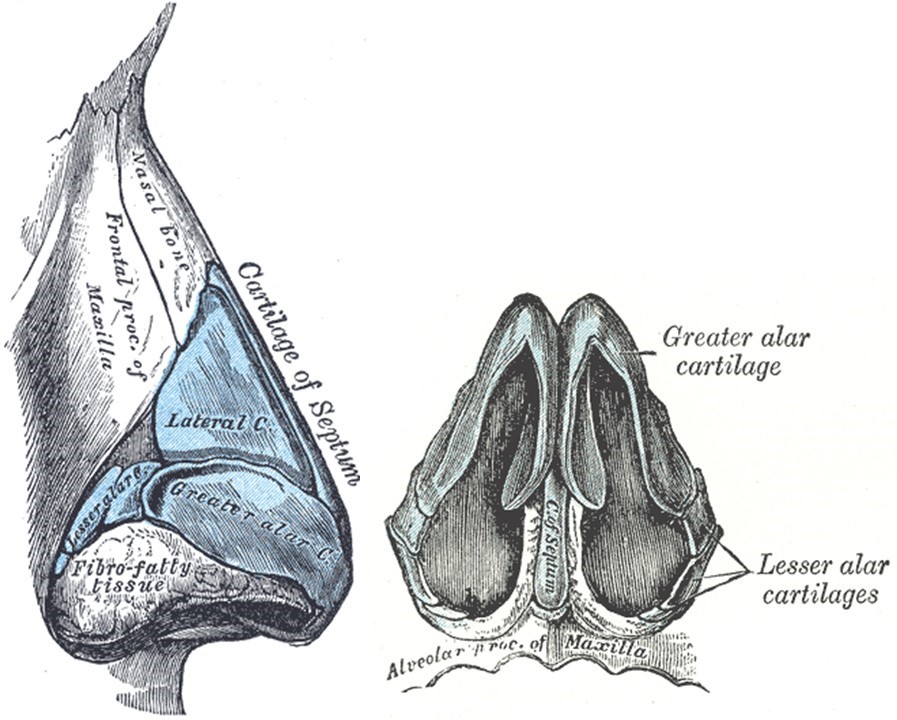

The structural support of the nose primarily consists of cartilage, bone, and skin. The paired nasal bones are fused superiorly to the frontal bone and laterally to the frontal processes of the maxillae, connecting at the nasofrontal and nasomaxillary suture lines, respectively (see Image. The Nasal Bone—Articulation of Nasal and Lacrimal Bones With Maxilla). The nasal bones tend to be thicker above the level of the medial canthi.[3]

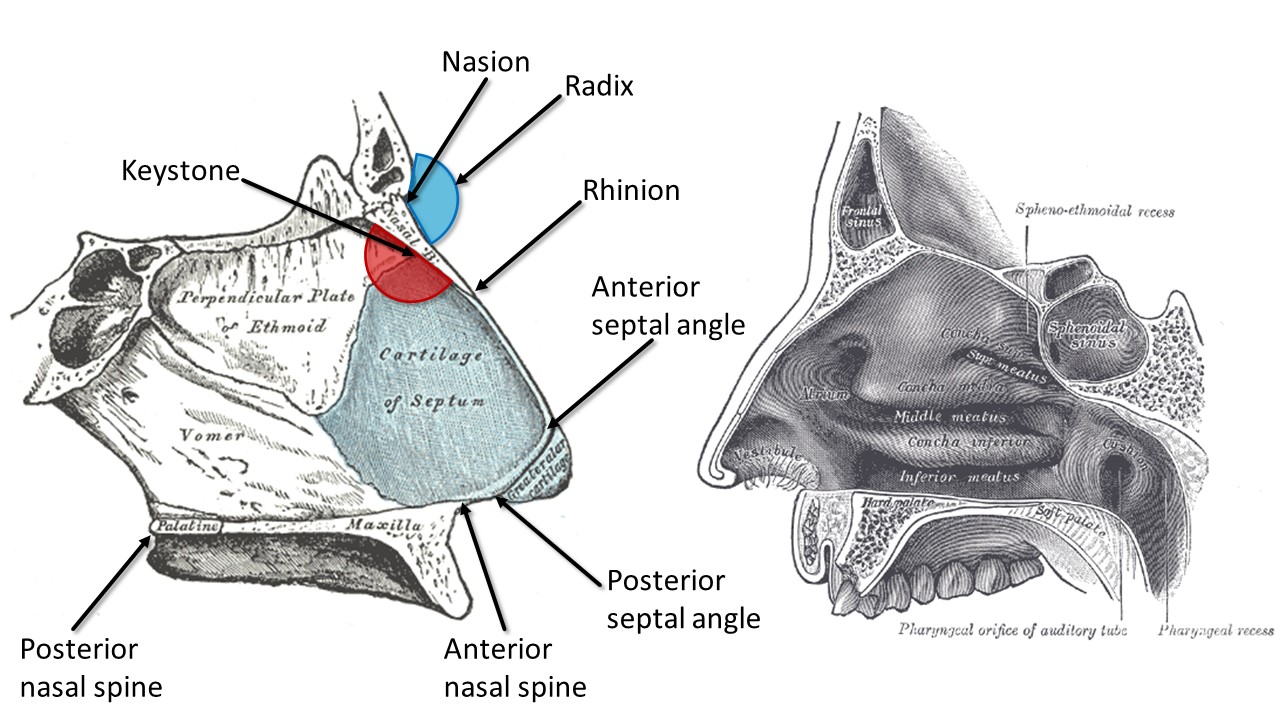

The nasal septum is composed of bone posteriorly and cartilage anteriorly. The bony septum is formed by the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone superiorly and the vomer inferiorly. These bones are connected to the quadrangular cartilage, which forms the anterior portion of the septum. The quadrangular cartilage supports the nasal dorsum, extending from the keystone area to the supratip of the nose.[3] The keystone area is a key structural support for the middle third of the nose, consisting of a 10 to 15 mm junction between the quadrangular cartilage and the ethmoid bone immediately inferior to the rhinion (see Image. Internal Nasal Anatomy).

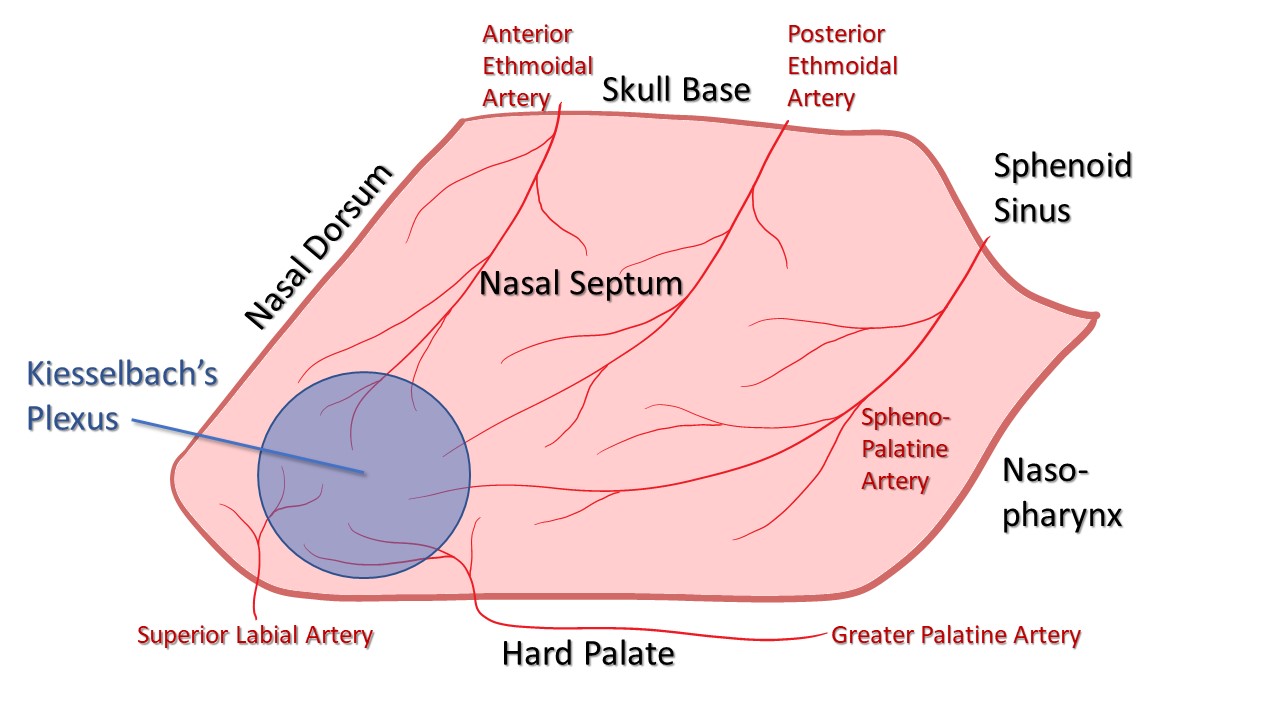

At the level of the keystone, the upper lateral cartilages connect with the caudal edges of the nasal bones. These cartilages are also attached to the dorsal margin of the cartilaginous septum. The septum is anchored to the nasal floor anteriorly at the nasal spine and posteriorly at the nasal crest of the maxilla and palatine bones. The blood supply to the nasal septum is provided by branches from both the internal and external carotid systems, including the anterior and posterior ethmoid arteries (from the internal carotid artery), the sphenopalatine and greater palatine arteries (from the maxillary branch of the external carotid artery), and the superior labial artery (from the facial branch of the external carotid artery) (see Image. Blood Supply of the Nasal Septum).

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Nasal bone fractures can occur through various mechanisms. Globally, the most common causes are interpersonal violence, motor vehicle accidents, sporting events, and falls. In North America, motor vehicle accidents are responsible for more nasal bone fractures than interpersonal violence.[4] In children, the most common causes of nasal bone fractures are sporting or motor vehicle accidents, depending on the source.[4][5] Interestingly, ball-related sports such as soccer, basketball, baseball, and rugby have a higher incidence of nasal bone fractures compared to fighting sports such as wrestling and martial arts.[4]

Epidemiology

Nasal bone and septal fractures are significantly more common in males than females, reflecting the higher incidence of interpersonal violence among males and their increased tendency for risk-taking behavior. The incidence of nasal bone fractures peaks during the second and third decades of life.[6][7]

In the United States, the rates of nasal bone and other facial fractures have steadily increased since 2000. However, repair rates have remained stable, which may indicate an increase in nonoperative fracture patterns, a trend toward more conservative management, and an increased use of computed tomography (CT) imaging to rule out fractures before proceeding with reduction.[7]

Pathophysiology

A frontal or lateral blow to the nose is the most common mechanism for fractures involving the nasal bones and nasal septum.[8] Fractures may be unilateral or bilateral and can present as nondisplaced, displaced, depressed, greenstick (incomplete), or comminuted.[9] Fractures may affect the nasal bones, lateral nasal cartilages, and septal cartilage. In severe, high-energy injuries, they can extend to the surrounding facial skeleton, leading to complex fractures such as Le Fort or naso-orbito-ethmoid complex fractures (see Image. External Nasal Skeleton). Please see StatPearls' companion resources, "Le Fort Fractures" and "Naso-Orbito-Ethmoid Fractures," for more information.

History and Physical

Patients with maxillofacial trauma should first undergo a primary trauma survey, evaluating the airway, breathing, circulation, neurological status, and environmental exposures. A comprehensive history and secondary physical examination should be conducted when life-threatening concerns have been addressed.

Determining the mechanism of trauma to the maxillofacial region is crucial. Higher-energy impacts, such as those from motor vehicle accidents, are more likely to result in severe injuries and multiple facial fractures. Understanding the direction of the impact can help identify the underlying fracture pattern. Lateral blows often cause inward displacement on the impacted side and outward displacement on the opposite side, whereas direct impacts to the nasal dorsum typically lead to splaying outfractures of both nasal bones.[10]

Understanding the patient's premorbid appearance is essential. Patients and their family members should be asked about any noticeable changes in the nose's appearance compared to before the injury. Difficulty breathing through either side of the nose should also be evaluated, as it may indicate intranasal edema or nasal septum injury.[11] The patient should also be questioned about any prior nasal trauma or surgeries, as these may impact the treatment plan and the discussion of treatment risks. Signs and symptoms suggesting more extensive injuries include telecanthus, diplopia, vision loss, clear rhinorrhea, malocclusion, facial weakness, and facial numbness.

The physical examination should comprehensively assess the entire head and neck region, including the skin, eyes, ears, and intraoral and intranasal areas. A detailed evaluation of the nasal dorsum and nasal cavity should be conducted using a headlamp and a nasal speculum or endoscope. The external nose should be inspected for lacerations or exposed bone and cartilage. Any mobility or deviation of the bony nasal pyramid must be documented. An increased intercanthal distance following trauma may suggest a naso-orbito-ethmoid fracture.[10] The nasal tip should be palpated to assess support, and the nasal dorsum should be examined for a saddle nose deformity, which may indicate a significant septal fracture or dislocation.[11]

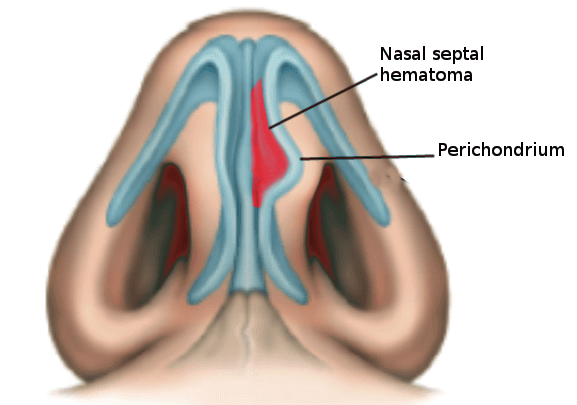

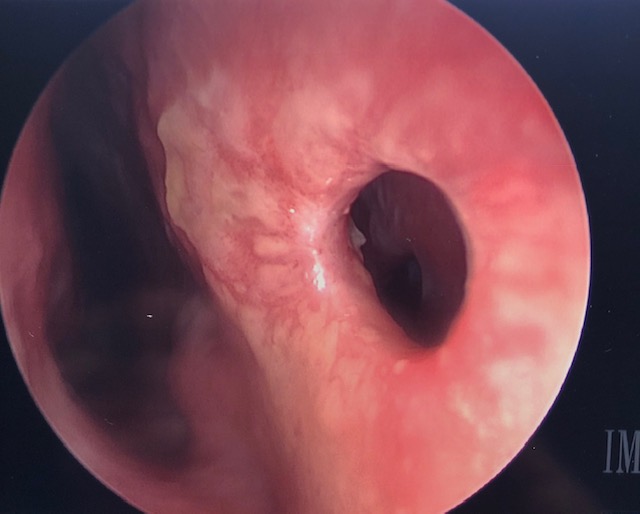

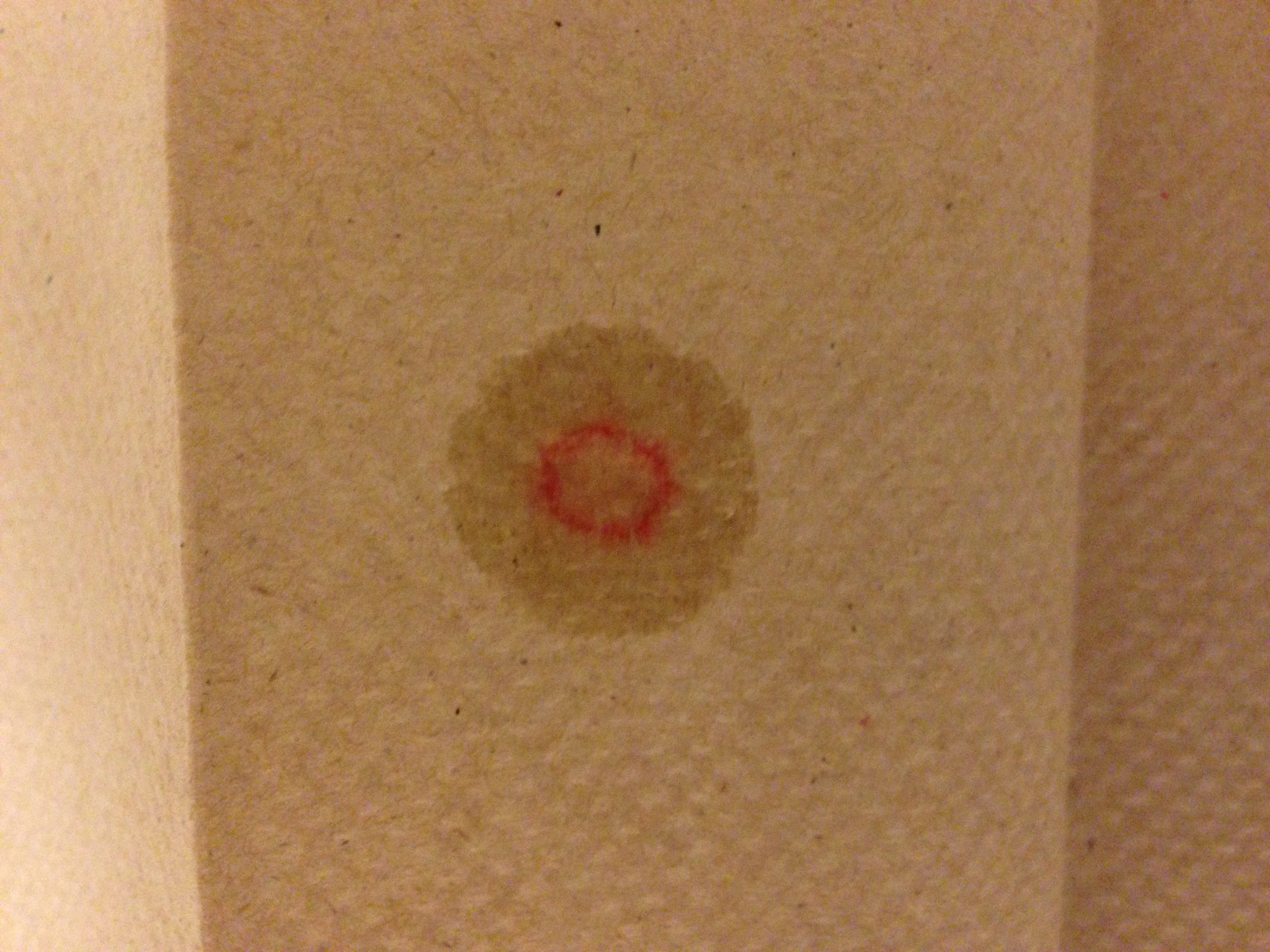

An intranasal examination should prioritize ruling out a septal hematoma, which presents as a fluctuant red or blue discoloration along the nasal septum, typically evident within 24 to 72 hours post-injury (see Image. Nasal Septal Hematoma in a Child).[12] Strong clinical suspicion for septal hematoma is warranted when nasal obstruction persists despite the use of topical vasoconstrictors (eg, 0.05% oxymetazoline) and the evacuation of blood clots. Significant septal dislocations should be documented, along with any intranasal lacerations or mucosal disruptions. Clear rhinorrhea, with or without a halo sign, should be carefully noted as it may indicate a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage (see Image. Halo Sign Indicating Cerebrospinal Fluid Leakage).[11]

Evaluation

Imaging is generally not warranted for simple nasal bone fractures, which are diagnosed clinically. Plain film x-rays are rarely used today; instead, CT of the facial bones without intravenous contrast has become the gold standard for evaluating bony trauma in the maxillofacial region when there is concern for more extensive facial injuries (see Image. Nasal Septal Fracture on Computed Tomography Without Contrast).[11] Neurological symptoms may warrant magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for further evaluation. The use of ultrasonography in diagnosing nasal bone fractures has recently been studied, but it has proven to be inferior to CT scanning.[13]

Laboratory evaluation is typically unnecessary for an isolated nasal fracture. However, a complete blood count and coagulation studies may be considered for patients with significant epistaxis, blood loss, or those on anticoagulant medications. For patients with persistent clear rhinorrhea, fluid may be collected and tested for β2-transferrin or β-trace protein to confirm or rule out the presence of a CSF leakage.

Treatment / Management

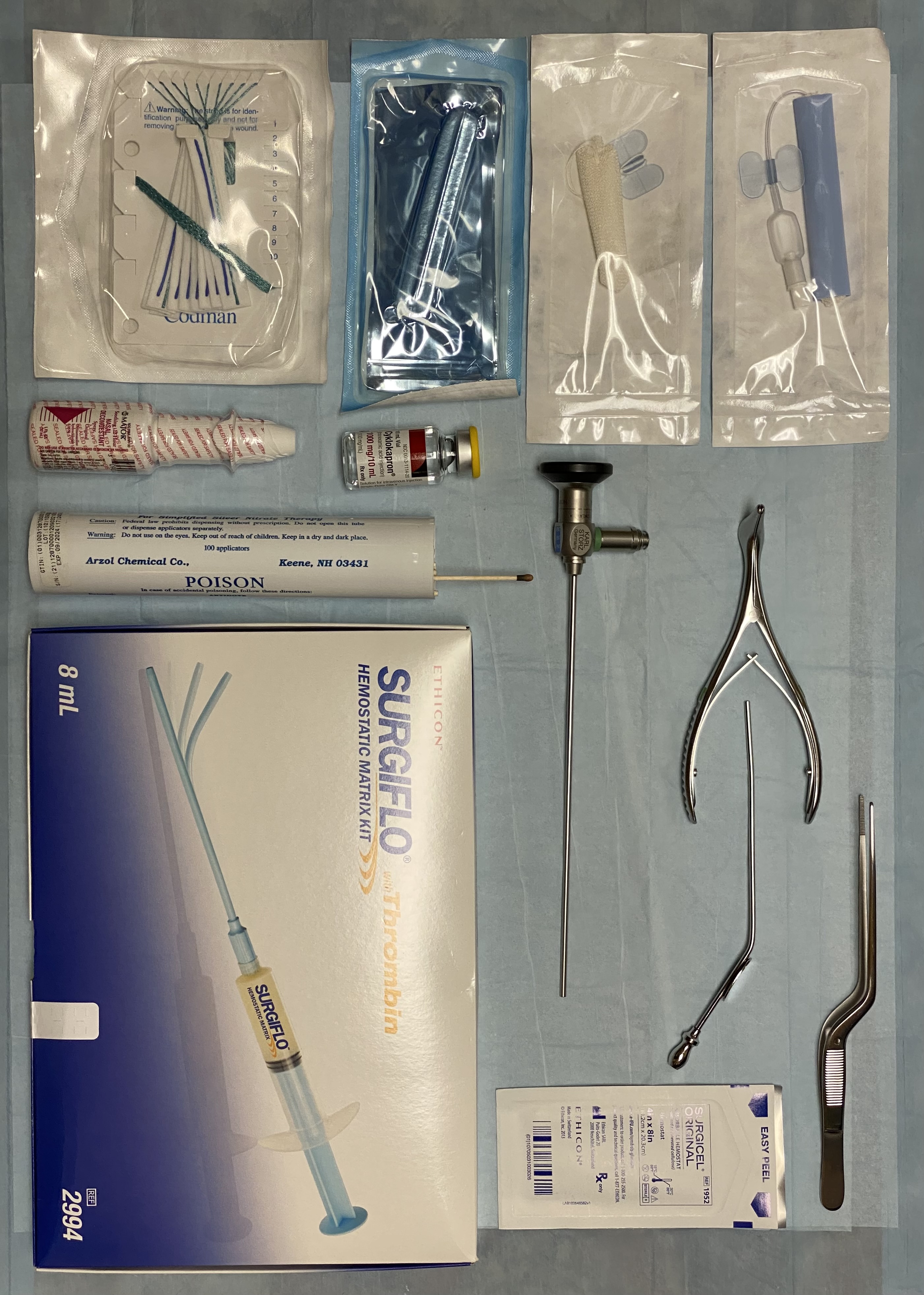

The initial management of nasal fractures focuses on controlling epistaxis and closing any cutaneous or mucosal lacerations whenever feasible. Epistaxis can often be managed conservatively by applying digital pressure to the nasal alae, compressing the anterior septum to occlude vessels within the Kiesselbach plexus, the most common site of nasal bleeding. More severe bleeding may require chemical or thermal cauterization or nasal packing (see Image. Supplies for Epistaxis Management). In cases of severe hemorrhage, endoscopic ligation of the sphenopalatine or ethmoid arteries, or angiographic embolization, may be necessary. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Epistaxis," for more information.

Observation without surgical intervention is recommended for patients with no apparent cosmetic deformity or nasal obstruction. Conservative measures, such as elevating the head and applying ice to the area, should be followed until local edema subsides. Patients should be reexamined within 3 to 5 days, as nasal deviation may become more evident as the edema resolves.[14]

Closed reduction of nasal bone and septal fractures is recommended for injuries that cause airway obstruction or a change in the appearance of the nose. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Nasal Fracture Reduction," for more information. Reduction can be performed under local anesthesia or with minimal sedation; however, general anesthesia is often preferred due to its advantages in airway protection and patient comfort. General anesthesia also provides a less stressful environment for the surgeon, allowing them to focus on achieving the best possible result without the added challenge of managing the patient's pain and anxiety.[10]

If reduction is performed under local anesthesia, various nerve blocks can be used to facilitate the procedure. These include infraorbital (4-7 mm inferior to the infraorbital rim in the midpupillary line), dorsal nasal (6-10 mm lateral to the midline along the inferior margin of the nasal bone), and nasociliary (1 cm above the medial canthus and 1.5 cm deep, along the medial border of the orbit). Epinephrine injection should be avoided in this area to prevent retinal artery spasms.[15] These injections will anesthetize the lateral nasal wall and medial cheek; the nasal dorsum, tip, and ala; and the nasal radix, septum, and lateral nasal cavity wall mucosa, respectively. When combined with a topical anesthetic solution (1%-4% lidocaine or 4% cocaine) applied via cottonoid pledgets, there is no significant difference in patient-reported pain between local and general anesthesia.[16]

The ideal timing for closed reduction is debated in the literature. Some authors advocate for early intervention within 5 to 7 days, while others recommend waiting until edema has completely resolved, typically 1 to 2 weeks after the injury.[10][11] However, patient satisfaction with cosmetic outcomes significantly decreases if the procedure is delayed beyond 2 weeks.[17] Delayed intervention carries the risk of callus formation and difficulty repositioning the nasal bones to their premorbid location, as the fractured segments may have already begun to heal. In such cases, an endonasal or percutaneous reduction can be performed, often involving osteotomies.[11] Using CT guidance to place osteotomies along healed fracture lines and facilitate precise reduction months to years after the injury has also been described as a valuable adjunct.[18] (B3)

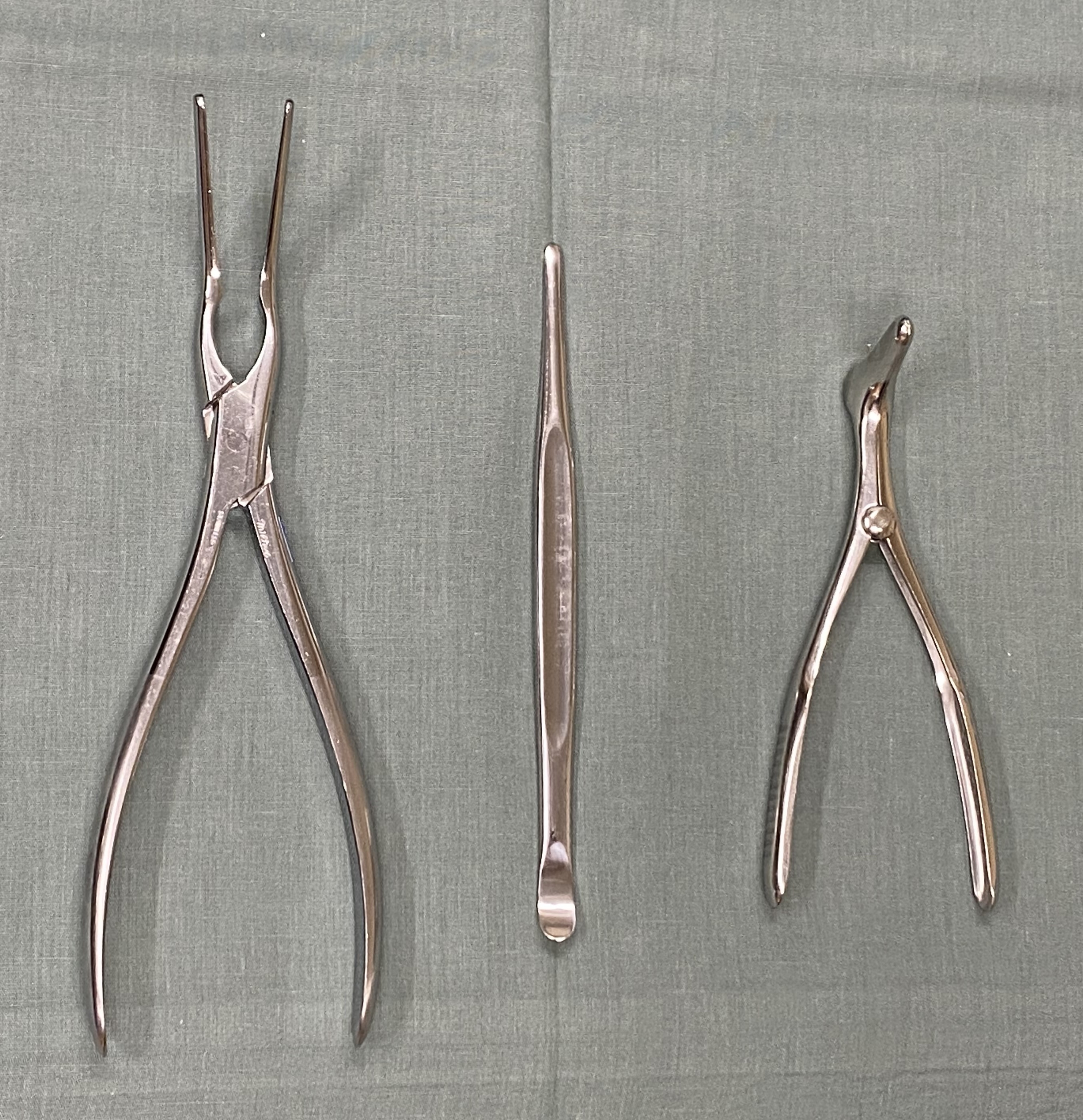

In a typical closed reduction, a flat, broad instrument, such as a Boies or Sayre elevator, is introduced endonasally to lift and reposition the fractured bony segments. A postoperative splint is then applied to the nasal dorsum. Closed reduction of the nasal septum can also be performed using a Sayre or Boies elevator or with Asch forceps, which grasp the septum atraumatically and reposition it back into the midline (see Image. Instruments for Closed Reduction of Nasal Fractures). If adequate reduction of the nasal septum cannot be achieved through closed methods, some authors recommend operative septoplasty in the acute setting, noting significant improvement in nasal obstruction postoperatively.[19](B2)

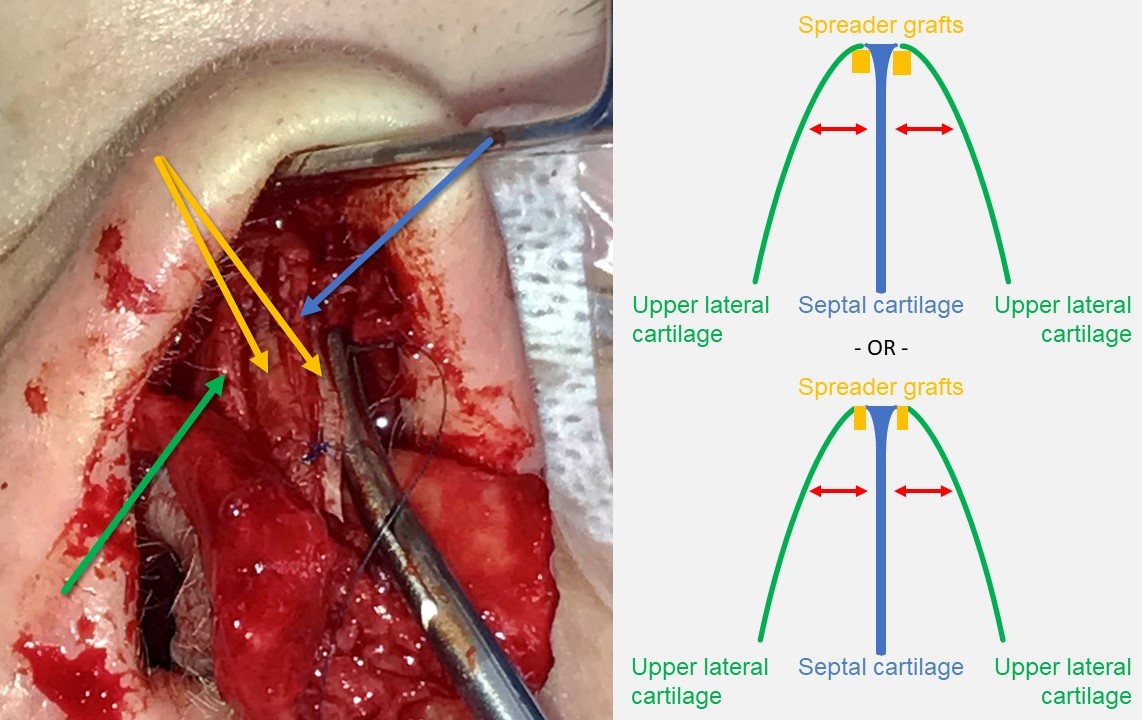

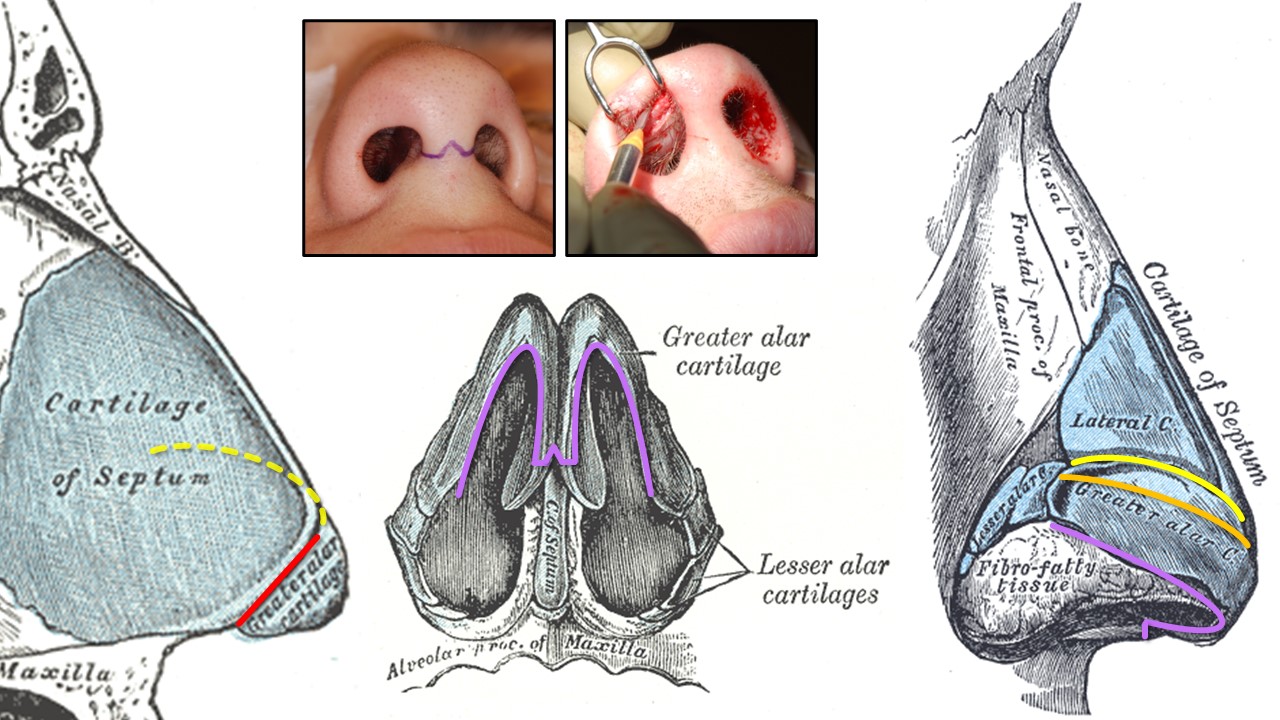

Intranasal splints or packing may also help maintain septal alignment after reduction, although these are typically unnecessary unless a septoplasty has been performed. Septoplasty is generally avoided if there is significant mucosal disruption along the septum due to the increased risk of postoperative septal perforation.[19] If septoplasty is performed in the acute setting, it is typically done through a hemitransfixion incision in the membranous septum along the caudal margin of the quadrangular cartilage (see Image. Rhinoplasty Incisions). Placing the incision on the concave side of the septal fracture can facilitate mucoperichondrial flap elevation (see Image. Hemitransfixion Incision for Septoplasty). The flap is elevated to expose the fractures, and the deviated portions of bone and cartilage are removed, except when they are located within 10 to 15 mm of the dorsal or caudal margins of the quadrangular cartilage. When fractures extend into this region, known as the "L-strut," access and repair are most effectively performed via an open septorhinoplasty.(B2)

Open septorhinoplasty via marginal incisions is generally avoided in the acute setting due to the frequent presence of lacerations or cartilage disruptions from nasal trauma (see Image. Open Rhinoplasty Approach). Further dissection of these cartilages can lead to devascularization, making cartilage grafts more prone to infection, extrusion, or absorption. For these reasons, septorhinoplasty is typically recommended to be delayed for 3 to 6 months after the injury.[20]

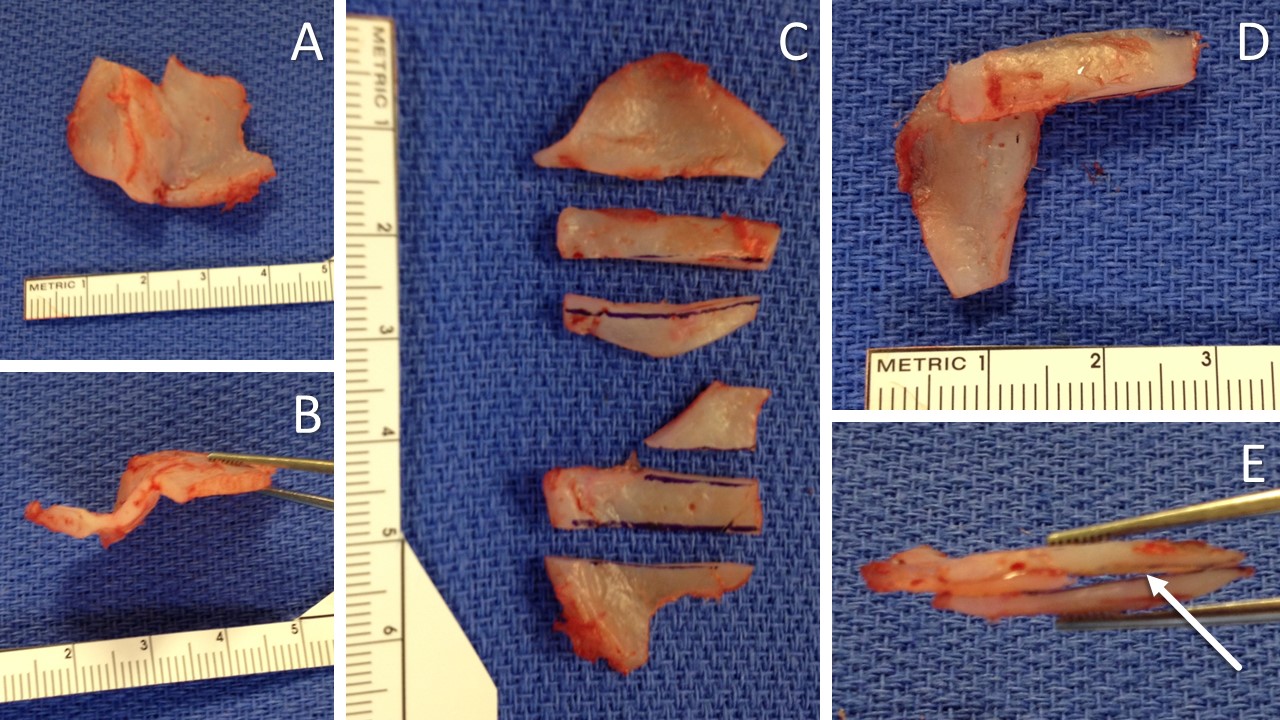

Repair of septal cartilage fractures within the L-strut is typically achieved by placing cartilage grafts to splint the fractured segments, maintaining their alignment and stability. Spreader grafts are commonly positioned along the dorsal aspect of the L-strut, whereas septal batten or septal extension grafts may be used on the caudal portion of the L-strut (see Image. Spreader Grafting). Severely fractured septal cartilage, often resulting from multiple nasal traumas, may require extracorporeal septoplasty (see Image. Extracorporeal Septal Reconstruction Using Native Quadrangular Cartilage). In this procedure, the L-strut is reconstructed using dorsal and caudal grafts, such as extended spreader grafts and caudal strut grafts (see Image. Surgical Correction of Saddle Nose Deformity).

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for nasal fractures should include bony injuries to the surrounding facial skeleton, as mentioned below.

Naso-Orbito-Ethmoid Complex Fracture

Nasal bone fractures may extend posteriorly into the ethmoid air cells and involve the medial canthus of one or both orbits. The hallmark of this condition is traumatic telecanthus (see Image. Naso-Orbito-Ethmoid Fracture). These fractures are also commonly observed in all Le Fort type III midface fractures.

Orbital Fracture

Periorbital edema or ecchymosis often suggests an orbital fracture. An orbital floor fracture may result in hypesthesia of the cheek due to injury to the infraorbital nerve or cause limitations in ocular movements from the entrapment of an extraocular muscle, typically the inferior rectus (see Image. Orbital Wall Fracture).

Skull Base Fracture

High-energy impacts can result in skull base fractures alongside fractures of the maxillofacial skeleton. Patients may exhibit characteristic bilateral periorbital ecchymosis, or "raccoon eyes," as well as postauricular ecchymosis, known as "Battle sign" (see Image. Skull Base Fractures). Patients with skull base fractures are at increased risk for developing CSF leaks and spinal fractures.

Prognosis

Patients typically recover well after nasal fracture reduction, although the success of surgical interventions can vary considerably. Persistent nasal deformity is reported in 9% to 50% of patients following closed reduction procedures.[14][20][21][22] Outcomes may improve with prompt management of nasal septal fractures or deviations at the time of injury.[2] Residual deformity or nasal obstruction can often be addressed later through septorhinoplasty. The likelihood of requiring revision surgery increases if nasal deformity or obstruction was present before the fracture occurred.[23]

Many surgeons avoid performing open rhinoplasty on patients involved in high-risk activities for nasal fractures, such as combat sports. They typically choose to defer the surgery until the patient discontinues these activities, aiming to reduce the risk of repeated nasal injuries and optimize the final surgical outcome.

Complications

Residual nasal deformity often persists to varying degrees following the reduction of nasal bone and septal fractures. Saddle nose deformities and septal perforations can occur as complications of septoplasty, septal hematoma formation, or significant septal injury. Olfactory disturbances are relatively common, affecting up to one-third of patients with nasal bone fractures. These disturbances may result from intraoperative manipulation of the olfactory neuroepithelium, located on the superior aspect of the nasal septum and the superior or supreme turbinate.[24]

Management of Septal Hematoma

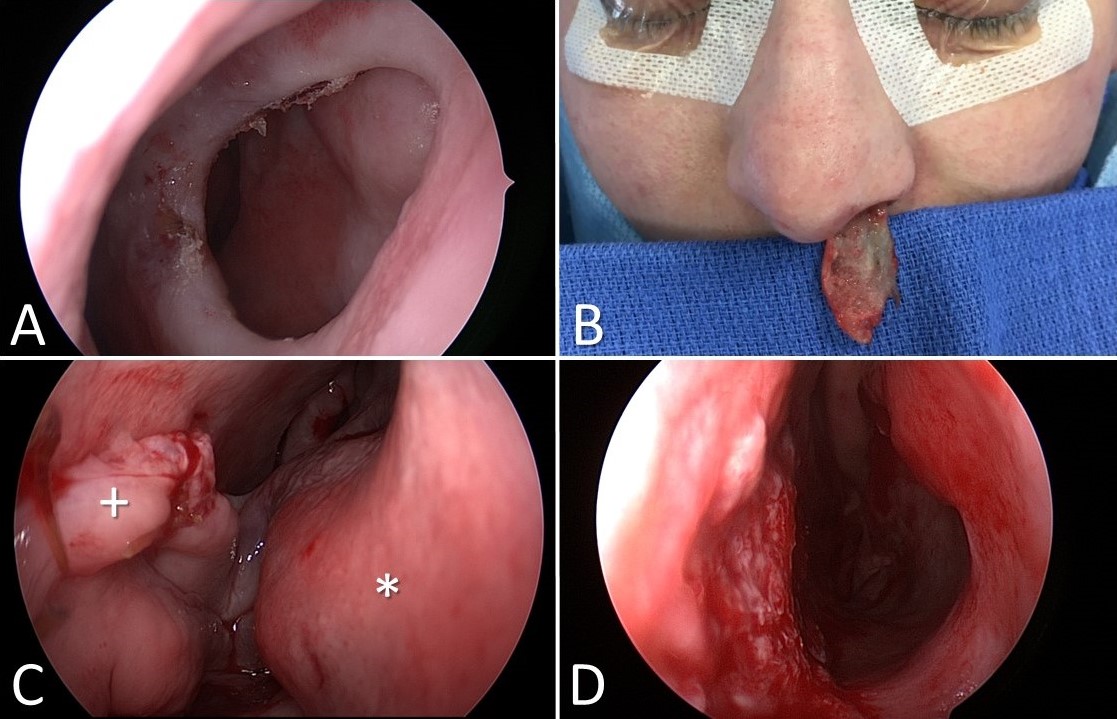

Subperichondrial hematomas of the nasal septum are most commonly caused by trauma, including iatrogenic injury during nasoseptal surgery, but they may occur spontaneously in patients with bleeding diatheses. Septal hematomas should be treated promptly after identification, as the collected blood can clot over time, making evacuation more difficult (see Image. Nasal Septal Hematoma).[25]

Prompt incision and drainage are essential to prevent abscess formation or septal cartilage necrosis. Cartilage necrosis can develop within a day due to ischemia from pressure on the cartilage, while abscesses may form within 72 hours, especially if mucosal disruptions allow nasal flora to access the hematoma, providing an ideal environment for bacterial growth. Over time, significant cartilage necrosis may result in septal perforation and saddle nose deformity.[12]

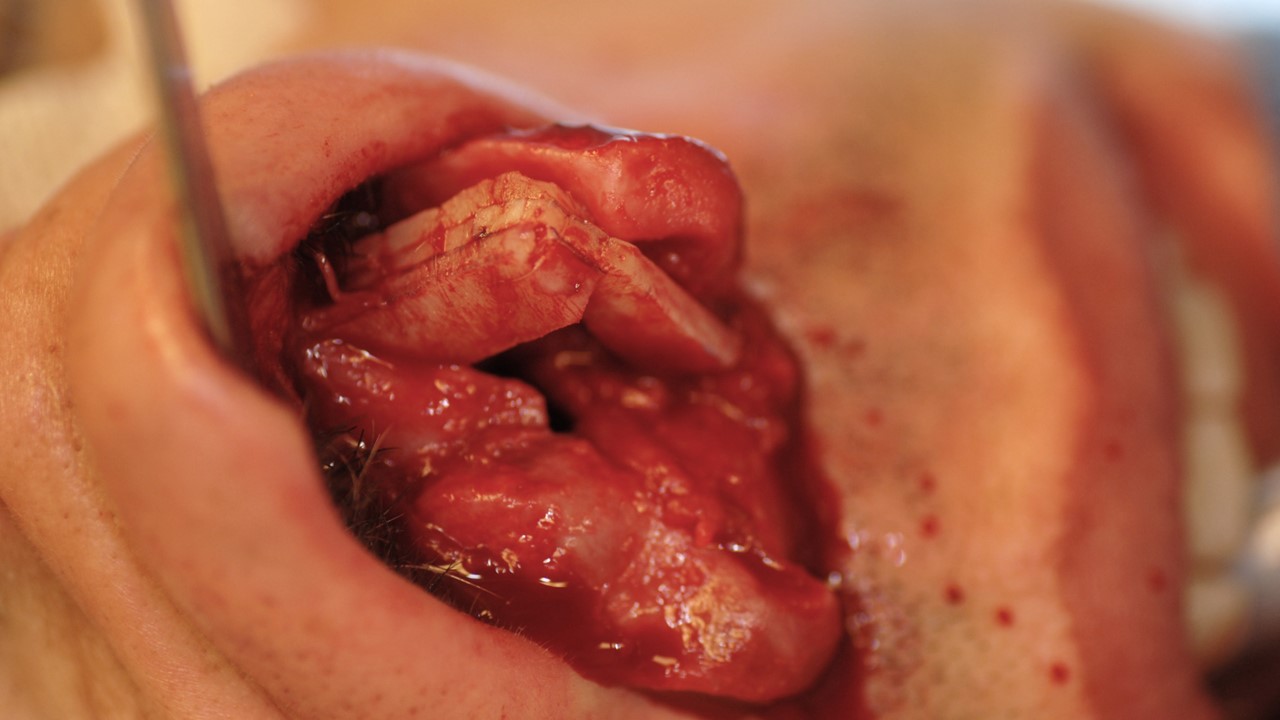

To evacuate a septal hematoma, appropriate anesthesia is administered, typically involving topical application of 1% to 4% lidocaine or 4% cocaine on cottonoid pledgets, with potential supplementation of local infiltration using 1% to 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000-200,000 epinephrine. Pediatric patients and adults who cannot cooperate with the procedure may require general anesthesia. A headlight and a nasal speculum (Vienna or Cottle) are typically used to visualize the hematoma, although a nasal endoscope may be an alternative. For smaller hematomas, aspiration with an 18- to 20-gauge hypodermic needle is often effective, especially if the hematoma is relatively fresh and has not yet consolidated. For larger or older hematomas, a horizontal incision is made along the most fluctuant portion of the hematoma, parallel to the floor of the nose.

Some surgeons may also excise a thin strip of mucoperichondrium to widen the incision and prevent premature closure, which could trap additional blood within the cavity if hemostasis is not achieved. The collected blood is expressed using a Freer elevator or similar instrument and then evacuated with a Frazier tip suction. A rubber band or thin Penrose drain is sutured into the wound for 3 to 5 days, and splints or quilting stitches are placed to eliminate dead space and prevent reaccumulation of the hematoma. If the hematoma is bilateral, incisions can be made on both sides of the septum, but they should be planned to avoid overlap, as this could create a full-thickness defect and increase the risk of developing a septal perforation.

Management of Septal Perforation

Perforations of the nasal septum range from asymptomatic microperforations, measuring less than a millimeter, to subtotal or total perforations that compromise critical support of the nasal dorsum, leading to significant aesthetic deficits (see Image. Nasal Septal Perforation). Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Septal Perforation," for more information. Due to septal fractures, perforations are often small to medium in size, typically occurring as sequelae of hematomas and subsequent tissue necrosis.

Symptomatic perforations can lead to crusting, bleeding, a sensation of nasal obstruction, and whistling, with the latter being more common in smaller perforations. Perforations up to 1-1.5 cm in diameter are often closed using local advancement or rotation flaps, along with an interposition graft of cartilage, fascia, acellular dermis, or a polydioxanone sheet.[26][27][28] Larger perforations are often treated with obturation using a septal button prosthesis but may also be closed with regional or free flaps. Described options for flap closure include inferior turbinate flaps, pericranial flaps, facial artery musculomucosal flaps, and radial forearm free fascial flaps (see Image. Inferior Turbinate Flap Reconstruction for Nasal Septal Perforation).[29][30][31][32]

Management of Saddle Nose Deformity

The collapse of the quadrangular cartilage and loss of dorsal projection in the middle third of the nose results in a "saddle nose" deformity, characterized by a depression between the rhinion and the nasal tip (see Image. Saddle Nose Deformity).[33] This condition can affect both nasal breathing and contour. The reduction in dorsal projection causes the upper lateral cartilages to collapse inward, obstructing the airway at the internal nasal valves—the narrow area in the superior part of the nasal passages where the upper lateral cartilages meet the dorsal septum. Minor saddle deformities are typically treated with onlay grafting to restore normal dorsal contour. However, more severe saddle deformities, which are often associated with nasal obstruction, require reconstruction that includes resuspension of the upper lateral cartilages to their normal anatomical positions.

Rhinoplasty for a shallow saddle deformity may require nothing more than crushed or diced cartilage grafting, with or without fascia, vomer, or turbinate bone onlay, or can even be accomplished with dermal filler injections, such as hyaluronic acid.[34][33][35] However, saddle deformities extensive enough to cause nasal obstruction typically require repair of the L-strut via the extracorporeal septoplasty method described in the Treatment/Management section above. Patients who have undergone prior surgery or who have significant septal damage are unlikely to have enough residual quadrangular cartilage to fashion the necessary grafts. In these cases, costal cartilage is often used. However, some surgeons prefer using split calvarial bone, cantilevered off the nasal bones, to restore dorsal projection and resuspend the upper lateral cartilages, which also helps alleviate any concomitant nasal obstruction (see Images. Intraoperative View of Septal Reconstruction Using Costal Cartilage and Split Calvarial Bone Grafting).[36][37]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

External and internal nasal splints should be removed within 1 to 2 weeks. If nasal packing is used, oral antibiotics are commonly prescribed to prevent toxic shock syndrome, although the need for prophylactic antibiotics remains debated.[38] Strenuous activities and physical exertion that could further traumatize the nose should be avoided during the acute phase. Nasal saline sprays are recommended to maintain moisture in the nasal cavity and promote mucosal healing. Close follow-up is essential to monitor for any residual nasal deformity or obstruction, which may require revision surgery.

Consultations

An otolaryngologist, oral surgeon, or plastic surgeon experienced in managing facial trauma should be involved early in the care of patients with nasal bone and septal fractures.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Prevention strategies for nasal fractures are similar to those for other facial injuries. These include wearing seat belts while riding in automobiles, wearing helmets that protect the face during high-speed activities such as skiing and motorcycling, and using appropriate facial protection while participating in sports.[39][40] Many sports, such as rugby, cricket, baseball, basketball, and soccer, do not routinely require face protection, yet all have been associated with nasal fractures.[41]

Avoiding interpersonal violence and falls can also reduce the risk of nasal fractures. In this regard, reducing alcohol consumption may be an effective preventive measure.[42] Ground-level falls are another common cause of nasal fractures in the older population, and the risk of these injuries can be minimized by removing tripping hazards in the home, improving visibility at night, and selecting medication combinations that are less likely to cause disorientation, vertigo, and hypotension.[43]

When counseling patients who have sustained nasal fractures, it is important to set realistic expectations before performing reduction, given the risk of residual deformity or nasal obstruction. Reduction should be carried out as soon as practical after the injury, once edema has sufficiently subsided to accurately assess any bony or cartilaginous deviation.

Pearls and Other Issues

Key facts to keep in mind regarding nasal septal fracture include:

- The nasal bones are the most commonly fractured structures in the maxillofacial region.

- Many patients with nasal bone fractures also sustain injuries to the nasal septum, which may go unrecognized unless specifically evaluated.

- Imaging studies should be avoided in isolated nasal bone fractures unless the history or physical examination suggests more extensive injuries.

- Closed reduction of the nasal bones is most effective when performed within 2 weeks for optimal cosmetic outcomes, although delaying 3 to 5 days to allow edema to subside may facilitate a more precise reduction.

- Septoplasty may be considered in the acute setting for a severely deviated or fractured septum, provided there is no extensive mucosal injury.

- Septorhinoplasty for residual nasal deformity or nasal obstruction should be delayed for 3 to 6 months to allow time for the healing of lacerations and cartilaginous injuries.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Nasal bone fractures are common injuries that can have lasting effects on both the function and appearance of a patient's nose. Patients with nasal bone or septal fractures should be referred promptly to surgeons specializing in facial trauma. Early treatment with closed reduction can help avoid the need for more extensive surgery later. Emergency room physicians or primary care providers are typically the first clinicians these patients encounter. Recognizing concerning symptoms and promptly communicating with facial trauma specialists can improve patient outcomes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Internal Nasal Anatomy. The right image shows the lateral nasal wall and turbinates, and the left image shows the nasal septum. The blue region represents the radix, or root of the nose, while the red region highlights the keystone area, which is crucial to preserve during surgery for maintaining nasal structural support.

Contributed by MH Hohman, MD, FACS, and Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Blood Supply of the Nasal Septum. The anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries arise from the internal carotid artery. The sphenopalatine and greater palatine arteries branch off the external carotid artery via the internal maxillary artery. The superior labial artery is a terminal branch of the facial artery. These vessels converge at the Kiesselbach plexus, which is located in the Little area on the anteroinferior aspect of the nasal septum.

Contributed by MH Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Supplies for Epistaxis Management. This set includes various tools and materials for managing epistaxis. The upper left corner features 2 packages— 5.5 cm and 7.5 cm inflatable anterior nasal packs. Below them are an uninflatable sponge anterior nasal pack and cottonoid pledgets, which can be soaked in oxymetazoline, epinephrine, or cocaine before use. The lower center includes tranexamic acid, oxymetazoline, and silver nitrate cautery sticks. In the lower right is a hemostatic matrix, with dissolvable cellulose packing positioned above it to the right. The set also includes essential tools such as Bayonet forceps, a Frazier suction tip, a Vienna speculum, and a 0-degree rigid Hopkins rod endoscope. A headlight is typically utilized for enhanced visualization.

Contributed by MH Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Nasal Septal Hematoma in a Child. This image shows a nasal septal hematoma in a child resulting from nasal trauma, with bilateral bulges visible under the septal mucosa.

Kopacheva-Barsova G, Arsova S. The impact of the nasal trauma in childhood on the development of the nose in future. Maced J Med Sci. 2016;4(3):413-419. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2016.081.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Extracorporeal Septal Reconstruction Using Native Quadrangular Cartilage. The deviated and multiply-fractured septal cartilage is excised, leaving a small cartilage tab at the keystone area to enable suture fixation of the reconstructed framework (A). A bird’s-eye view of the quadrangular cartilage shows the severe deviation (B). The quadrangular cartilage is divided into smaller sections, each selected for its relatively flat and fracture-free structure (C). An L-strut is constructed using 2 extended spreader grafts and a caudal septal replacement graft (D). A bird’s eye view of the L-strut construct, depicting the space between the spreader grafts (arrow), designed to accommodate the cartilage tab at the keystone area (E).

Contributed by MH Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Surgical Correction of Saddle Nose Deformity. Preoperative and postoperative views of a 30-year-old male with a saddle nose deformity resulting from repeated nasal trauma due to boxing. The left image is the preoperative view, and the right image is the postoperative view 1 month after open septorhinoplasty and septal reconstruction using costal cartilage.

Contributed by MH Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Spreader Grafting. The spreader grafts (yellow arrows), crafted from harvested septal cartilage, are sutured to both sides of the dorsal septal cartilage (blue arrow). The upper lateral cartilages (green arrow) are then either suspended to the spreader grafts or draped over them and sutured directly to the dorsal septum. This technique opens the internal nasal valve and straightens the dorsum, although it may result in a widened dorsal aesthetic.

Contributed by MH Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Naso-Orbito-Ethmoid Fracture. A 32-year-old male underwent naso-orbito-ethmoid fracture repair 12 months ago following a motor vehicle accident, with open repair of nasal fractures and transnasal wires. He now presents with intermittent tearing from the right side and mucoid discharge from the left. The images show the appearance at the time of injury (above) and 12 months after repair (below).

Contributed by BCK Patel, MD, FRCS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

The Nasal Bone—Articulation of Nasal and Lacrimal Bones With Maxilla.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

External Nasal Skeleton. The left image represents the lateral view, and the right image represents the basal view. The “greater alar cartilages” labeled in the illustration are more commonly referred to as “lower lateral cartilages,” and the “lateral cartilages” are more commonly called the “upper lateral cartilages.” Additionally, the "lesser alar cartilages" are also known as "sesamoid cartilages."

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Rhinoplasty Incisions. The red line denotes a transfixion incision used for endonasal septoplasty (unilateral hemitransfixion) or tip-delivery rhinoplasty (full transfixion—through the membranous septum). Yellow indicates an intercartilaginous incision between the upper and lower lateral cartilages at the scroll, used for closed or tip-delivery rhinoplasty when made in continuity with a transfixion incision (dashed yellow line). Orange represents an intracartilaginous incision used for cephalic trimming with an intercartilaginous incision during closed rhinoplasty. Purple denotes marginal incisions along the inferior edges of the lower lateral cartilages for open rhinoplasty. This is also used for tip delivery when the transcolumellar portion is omitted. Photos illustrate the "inverted-V" transcolumellar incision used for open rhinoplasty (left) and the marginal incision for tip delivery without the transcolumellar portion (right).

Contributed by MH Hohman, MD, FACS, and Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Open Rhinoplasty Approach. The marginal incisions are marked with an “inverted-V” transcolumellar portion (A). The transcolumellar portion is made using a scalpel, followed by the rest of the marginal incisions with scissors (B). The skin-soft tissue envelope is dissected off the lateral crura of the lower lateral cartilages (C). The upper lateral cartilages are exposed (D). The interdomal ligaments are divided to reveal the septal cartilage between the lower lateral cartilages (E). Nasal tip anatomy viewed through an open rhinoplasty approach. The medial crura are indicated by single asterisks, and the lateral crura are indicated by double asterisks. Stars mark the tip-defining points of the domes (F).

Contributed by MH Hohman, MD, FACS, and C Llewellyn, MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Inferior Turbinate Flap Reconstruction for Nasal Septal Perforation. Nasal septal perforation (A). The left inferior turbinate is separated from the lateral nasal wall and incised along its length to permit the removal of the conchal bone while remaining pedicled anteriorly (B). The flap is transferred and inset into the septal perforation (the plus sign indicates the flap and the asterisk marks the remaining in situ anterior face of the inferior turbinate, with the pedicle running across the nasal cavity between them (C). The pedicle is divided 3 weeks later, leaving a patent nasal cavity and an intact nasal septum (D).

Contributed by MH Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Split Calvarial Bone Grafting. For significant saddle nose deformities with cartilaginous septal insufficiency, reconstruction using a split calvarial onlay graft offers support to the nasal dorsum and tip. The graft is either placed into a tight subperiosteal pocket or secured with screws for stability.

Contributed by MH Hohman, MD, FACS

References

Rhee SC, Kim YK, Cha JH, Kang SR, Park HS. Septal fracture in simple nasal bone fracture. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2004 Jan:113(1):45-52 [PubMed PMID: 14707621]

Arnold MA, Yanik SC, Suryadevara AC. Septal fractures predict poor outcomes after closed nasal reduction: Retrospective review and survey. The Laryngoscope. 2019 Aug:129(8):1784-1790. doi: 10.1002/lary.27781. Epub 2018 Dec 28 [PubMed PMID: 30593703]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceOneal RM, Beil RJ. Surgical anatomy of the nose. Clinics in plastic surgery. 2010 Apr:37(2):191-211. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2009.12.011. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20206738]

Hwang K, Ki SJ, Ko SH. Etiology of Nasal Bone Fractures. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2017 May:28(3):785-788. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000003477. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28468166]

Desrosiers AE 3rd, Thaller SR. Pediatric nasal fractures: evaluation and management. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2011 Jul:22(4):1327-9. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31821c932d. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21772190]

Yu H, Jeon M, Kim Y, Choi Y. Epidemiology of violence in pediatric and adolescent nasal fracture compared with adult nasal fracture: An 8-year study. Archives of craniofacial surgery. 2019 Aug:20(4):228-232. doi: 10.7181/acfs.2019.00346. Epub 2019 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 31462013]

VandeGriend ZP, Hashemi A, Shkoukani M. Changing trends in adult facial trauma epidemiology. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2015 Jan:26(1):108-12. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000001299. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25534050]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceStranc MF, Robertson GA. A classification of injuries of the nasal skeleton. Annals of plastic surgery. 1979 Jun:2(6):468-74 [PubMed PMID: 543615]

Lu GN, Humphrey CD, Kriet JD. Correction of Nasal Fractures. Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 2017 Nov:25(4):537-546. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2017.06.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28941506]

Fattahi T, Salman S. Management of Nasal Fractures. Atlas of the oral and maxillofacial surgery clinics of North America. 2019 Sep:27(2):93-98. doi: 10.1016/j.cxom.2019.04.002. Epub 2019 Jun 6 [PubMed PMID: 31345495]

Hoffmann JF. An Algorithm for the Initial Management of Nasal Trauma. Facial plastic surgery : FPS. 2015 Jun:31(3):183-93. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1555618. Epub 2015 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 26126215]

Sanyaolu LN, Farmer SE, Cuddihy PJ. Nasal septal haematoma. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2014 Nov 4:349():g6075. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g6075. Epub 2014 Nov 4 [PubMed PMID: 25370844]

Lee IS, Lee JH, Woo CK, Kim HJ, Sol YL, Song JW, Cho KS. Ultrasonography in the diagnosis of nasal bone fractures: a comparison with conventional radiography and computed tomography. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2016 Feb:273(2):413-8. doi: 10.1007/s00405-015-3595-8. Epub 2015 Mar 8 [PubMed PMID: 25749616]

Rohrich RJ, Adams WP Jr. Nasal fracture management: minimizing secondary nasal deformities. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2000 Aug:106(2):266-73 [PubMed PMID: 10946923]

Zide BM, Swift R. How to block and tackle the face. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1998 Mar:101(3):840-51 [PubMed PMID: 9500408]

Jana S, Guha R, De KS, Adhikari B, Das P. Nasal Bone Fracture Reduction Under Local Anaesthesia: A Holistic Approach to Nasal Blocks and a Comparison with General Anaesthesia. Indian journal of otolaryngology and head and neck surgery : official publication of the Association of Otolaryngologists of India. 2024 Feb:76(1):358-364. doi: 10.1007/s12070-023-04163-9. Epub 2023 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 38440457]

Sharma SD, Kwame I, Almeyda J. Patient aesthetic satisfaction with timing of nasal fracture manipulation. Surgery research and practice. 2014:2014():238520. doi: 10.1155/2014/238520. Epub 2014 Jan 2 [PubMed PMID: 25374948]

Wick EH, Whipple ME, Hohman MH, Moe KS. Computer-Aided Rhinoplasty Using a Novel "navigated" Nasal Osteotomy Technique: A Pilot Study. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2021 Oct:130(10):1148-1155. doi: 10.1177/0003489421996846. Epub 2021 Mar 1 [PubMed PMID: 33641434]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYounes A, Elzayat S. The role of septoplasty in the management of nasal septum fracture: a randomized quality of life study. International journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery. 2016 Nov:45(11):1430-1434. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2016.06.001. Epub 2016 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 27338674]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWang W, Lee T, Kohlert S, Kadakia S, Ducic Y. Nasal Fractures: The Role of Primary Reduction and Secondary Revision. Facial plastic surgery : FPS. 2019 Dec:35(6):590-601. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1700801. Epub 2019 Nov 29 [PubMed PMID: 31783414]

James JG, Izam AS, Nabil S, Rahman NA, Ramli R. Closed and Open Reduction of Nasal Fractures. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2020 Jan/Feb:31(1):e22-e26. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000005812. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31449209]

Basheeth N, Donnelly M, David S, Munish S. Acute nasal fracture management: A prospective study and literature review. The Laryngoscope. 2015 Dec:125(12):2677-84. doi: 10.1002/lary.25358. Epub 2015 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 25959006]

Li K, Moubayed SP, Spataro E, Most SP. Risk Factors for Corrective Septorhinoplasty Associated With Initial Treatment of Isolated Nasal Fracture. JAMA facial plastic surgery. 2018 Dec 1:20(6):460-467. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2018.0336. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29902309]

Hwang K, Yeom SH, Hwang SH. Complications of Nasal Bone Fractures. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2017 May:28(3):803-805. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000003482. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28468171]

Kass JI, Ferguson BJ. Videos in clinical medicine. Treatment of hematoma of the nasal septum. The New England journal of medicine. 2015 May 28:372(22):e28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMvcm1010616. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26017844]

Pedroza F, Patrocinio LG, Arevalo O. A review of 25-year experience of nasal septal perforation repair. Archives of facial plastic surgery. 2007 Jan-Feb:9(1):12-8 [PubMed PMID: 17224482]

Kridel RWH, Delaney SW. Discussion: Acellular Human Dermal Allograft as a Graft for Nasal Septal Perforation Reconstruction. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2018 Jun:141(6):1525-1527. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000004434. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29794710]

Ozturan O, Yenigun A, Senturk E, Eren SB, Aksoy F. Endoscopic Endonasal Repair of Septal Perforation with Interpositional Auricular Cartilage Grafting via a Mucosal Regeneration Technique. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2016 Oct:155(4):714-7. doi: 10.1177/0194599816659277. Epub 2016 Jul 12 [PubMed PMID: 27406706]

Xu M, He Y, Bai X. Effect of Temporal Fascia and Pedicle Inferior Turbinate Mucosal Flap on Repair of Large Nasal Septal Perforation via Endoscopic Surgery. ORL; journal for oto-rhino-laryngology and its related specialties. 2016:78(6):303-307. doi: 10.1159/000453269. Epub 2016 Dec 16 [PubMed PMID: 27978529]

Waters CM, Zanation AM, Thorp BD, Shockley WW, Clark JM. Repair of Septal Perforation with Endoscopic-Assisted Pericranial Flap Harvest and Open Rhinoplasty Approach. Facial plastic surgery & aesthetic medicine. 2020 May/Jun:22(3):225-226. doi: 10.1089/fpsam.2020.0008. Epub 2020 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 32212970]

Heller JB, Gabbay JS, Trussler A, Heller MM, Bradley JP. Repair of large nasal septal perforations using facial artery musculomucosal (FAMM) flap. Annals of plastic surgery. 2005 Nov:55(5):456-9 [PubMed PMID: 16258293]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMobley SR, Boyd JB, Astor FC. Repair of a large septal perforation with a radial forearm free flap: brief report of a case. Ear, nose, & throat journal. 2001 Aug:80(8):512 [PubMed PMID: 11523466]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGadkaree SK, Weitzman RE, Fuller JC, Justicz N, Gliklich RE. Review of literature of saddle nose deformity reconstruction and presentation of vomer onlay graft. Laryngoscope investigative otolaryngology. 2020 Dec:5(6):1039-1043. doi: 10.1002/lio2.475. Epub 2020 Oct 16 [PubMed PMID: 33364391]

Kim DW, Toriumi DM. Management of posttraumatic nasal deformities: the crooked nose and the saddle nose. Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 2004 Feb:12(1):111-32 [PubMed PMID: 15062242]

Gurlek A, Askar I, Bilen BT, Aydogan H, Fariz A, Alaybeyoglu N. The use of lower turbinate bone grafts in the treatment of saddle nose deformities. Aesthetic plastic surgery. 2002 Nov-Dec:26(6):407-12 [PubMed PMID: 12621560]

Cheney ML, Gliklich RE. The use of calvarial bone in nasal reconstruction. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 1995 Jun:121(6):643-8 [PubMed PMID: 7772316]

Furlan S. Correction of saddle nose deformities by costal cartilage grafts--a technique. Annals of plastic surgery. 1982 Jul:9(1):32-5 [PubMed PMID: 7125512]

Ishii LE, Tollefson TT, Basura GJ, Rosenfeld RM, Abramson PJ, Chaiet SR, Davis KS, Doghramji K, Farrior EH, Finestone SA, Ishman SL, Murphy RX Jr, Park JG, Setzen M, Strike DJ, Walsh SA, Warner JP, Nnacheta LC. Clinical Practice Guideline: Improving Nasal Form and Function after Rhinoplasty Executive Summary. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2017 Feb:156(2):205-219. doi: 10.1177/0194599816683156. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28145848]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHwang K, Kim JH. Effect of Restraining Devices on Facial Fractures in Motor Vehicle Collisions. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2015 Sep:26(6):e525-7. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000002030. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26267585]

Perkins CS, Layton SA. The aetiology of maxillofacial injuries and the seat belt law. The British journal of oral & maxillofacial surgery. 1988 Oct:26(5):353-63 [PubMed PMID: 3191086]

Manninen IK, Klockars T, Mäkinen LK, Blomgren K. Epidemiology and aetiology of sport-related nasal fractures: Analysis of 599 Finnish patients. Clinical otolaryngology : official journal of ENT-UK ; official journal of Netherlands Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology & Cervico-Facial Surgery. 2023 Jan:48(1):70-74. doi: 10.1111/coa.13976. Epub 2022 Sep 9 [PubMed PMID: 36054526]

Lee K, Olsen J, Sun J, Chandu A. Alcohol-involved maxillofacial fractures. Australian dental journal. 2017 Jun:62(2):180-185. doi: 10.1111/adj.12471. Epub 2016 Dec 27 [PubMed PMID: 27743391]

Clyburn TA, Heydemann JA. Fall prevention in the elderly: analysis and comprehensive review of methods used in the hospital and in the home. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2011 Jul:19(7):402-9 [PubMed PMID: 21724919]