Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is characterized by episodes of complete (apnea) or partial (hypopnea) collapse of the upper airway, leading to decreased oxygen desaturation or arousal from sleep.[1] This disruption results in fragmented and nonrestorative sleep. Other symptoms include loud and disruptive snoring, witnessed apneas during sleep, and excessive daytime sleepiness.[2][3][4] OSA significantly affects cardiovascular health, behavioral conditions, quality of life, and driving safety.[5] Other types of sleep-disordered breathing, including central sleep apnea, upper airway resistance, and obesity hypoventilation, will be discussed separately. Please see StatPearls' companion resources, "Central Sleep Apnea" and "Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome," for more information.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Pharyngeal narrowing and closure during sleep is a complex phenomenon influenced by multiple factors. Sleep-related reductions in ventilatory drive, neuromuscular factors, and anatomical risk factors all contribute significantly to upper airway obstruction during sleep.[1]

Anatomical factors that promote pharyngeal narrowing include a large neck circumference, excess soft tissue, bony structures, or blood vessels.[6] Many of these structures can increase pressure around the upper airway, leading to pharyngeal collapsibility and insufficient space for airflow in part of the upper airway during sleep.[7]

In addition, the upper airway muscle tone is crucial; when muscle tone decreases, it leads to a repetitive total or partial airway collapse. OSA in adults is most commonly associated with obesity, male sex, and advancing age.[8]

Anatomical Factors

- Micrognathia and retrognathia

- Facial elongation

- Mandibular hypoplasia

- Adenoid and tonsillar hypertrophy

- Inferior displacement of the hyoid

Nonanatomical Risk Factors

- Central fat distribution

- Obesity

- Advanced age

- Male gender

- Supine sleeping position

- Pregnancy [9]

Additional Factors

- Alcohol use

- Smoking

- Use of sedatives and hypnotics

Associated Medical Disorders

- Endocrine disorders (eg, diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, acromegaly, and hypothyroidism) [10][11]

- Neurological disorders (eg, stroke, spinal cord injury, and myasthenia gravis) [12][13]

- Prader-Willi syndrome [14]

- Down Syndrome [15]

- Congestive heart failure [16]

- Atrial fibrillation [17]

- Obesity hypoventilation syndrome

These associations between OSA and various medical disorders are primarily based on observational studies rather than randomized clinical trials.

Epidemiology

OSA is a common condition with significant adverse consequences.[18] Using the definition of 5 or more events per hour, OSA affects almost 1 billion people globally,[19] with 425 million adults aged between 30 to 69 having moderate-to-severe OSA (15 or more events per hour).[20]

In the United States, it has been reported that 25% to 30% of men and 9% to 17% of women meet the criteria for OSA.[21][22] Prevalence is higher in Hispanic, Black, and Asian populations. Prevalence also increases with age, and when individuals are 50 years or older, and as many women as men develop the disorder. The increasing prevalence of OSA is related to the rising rates of obesity, ranging between 14% and 55%.[21] Some risk factors, including obesity and upper airway soft tissue structure, are genetically inherited.[23]

Pathophysiology

Upper airway obstruction during sleep is often caused by negative collapsing pressure during inspiration; however, progressive expiratory narrowing in the retropalatal area also has a significant role.[24] The magnitude of upper airway narrowing during sleep is often related to body mass index (BMI), indicating that both anatomical and neuromuscular factors contribute to airway obstruction.[25] The pressure-flow relationship through collapsible tubes is key to understanding the mechanisms of OSA.[26] Additional information on risk factors is available in the Etiology section.

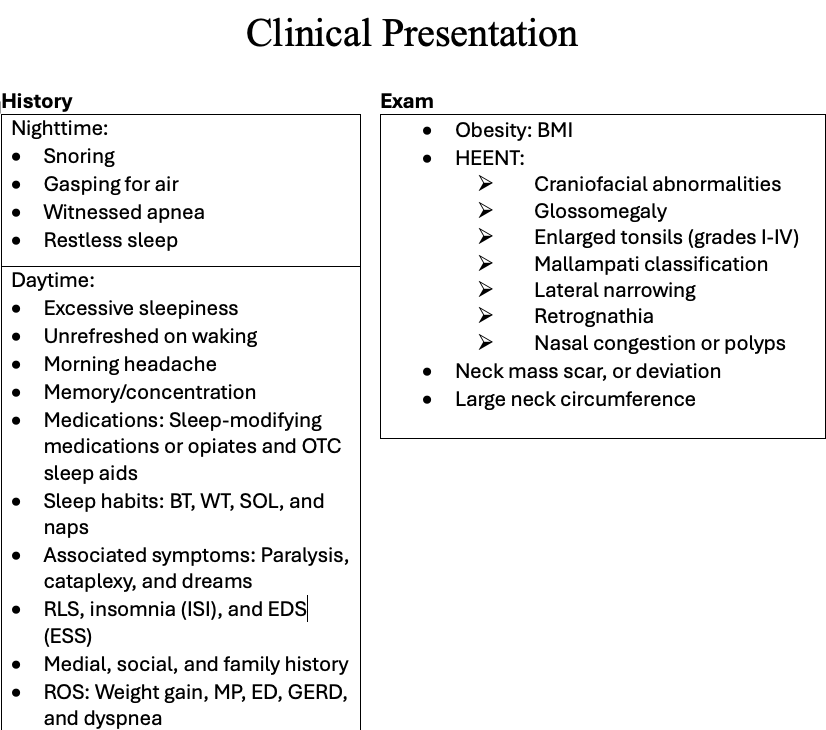

History and Physical

Patients with suspected OSA usually present with excessive daytime sleepiness, loud snoring, gasping, choking, or witnessed episodes of breathing cessation during sleep. Excessive daytime sleepiness is one of the most common symptoms.[22]

Many patients may only report daytime fatigue, with or without other associated symptoms. Therefore, it is important to objectively assess the distinction between sleepiness and fatigue. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) can be used to quantitatively evaluate the severity of sleepiness.[27] The ESS score ranges from 0 to 24; a score above 9 suggests excessive daytime sleepiness and warrants additional assessment. The Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) can also be used to assess the severity of fatigue symptoms.[28]

The ESS and FSS are helpful tools, as sleepiness and fatigue symptoms may occur concurrently. Other symptoms may include morning headaches, nocturnal reflux, insomnia, and nocturia.[29][30][31] Symptoms of sleep-onset and sleep-maintenance insomnia are more commonly reported by women.[32]

The STOP-BANG questionnaire is one of the most widely accepted screening tools for OSA.[33]

- Snoring: Do you snore loudly (louder than talking or loud enough to be heard through closed doors)?

- Tired: Do you often feel tired, fatigued, or sleepy during the daytime?

- Observed: Has anyone observed you stop breathing during your sleep?

- Blood pressure: Are you currently being treated for high blood pressure?

- BMI: Is your BMI greater than 35 kg/m2?

- Age: Are you of age 50 or older?

- Neck circumference: Is your neck circumference greater than 40 cm?

- Sex: Are you male?

The STOP-BANG questionnaire can be used to assess the probability of moderate-to-severe OSA. A high risk is indicated if "YES" is selected for 5 or more items, while a low risk is indicated if "YES" is answered for fewer than 3 items.

Obesity is the most common finding in individuals with OSA. Other physical signs include a large neck circumference (17 inches or 43 cm in males and 16 inches or 40.5 cm in females), a crowded oropharynx (a Mallampati score of 3 to 4), retrognathia, micrognathia, tonsillar hypertrophy, low-lying palate, overjet, and a large tongue. However, lateral narrowing is the only independent predictor of OSA after adjusting for body weight and neck size (see Image. Clinical Assessment of Sleep Apnea).[34]

Evaluation

Adult patients with unexplained daytime or sleep-related symptoms, such as excessive sleepiness, fatigue, or unrefreshing sleep, should be evaluated for sleep apnea. However, universal screening for OSA is not recommended in asymptomatic patients, except for those at risk due to occupational hazards, such as drivers or pilots.[35][36] In addition, due to the high prevalence of OSA and its disease burden, patients with specific comorbidities, including refractory atrial fibrillation, resistant hypertension, and a history of stroke, should also be screened for sleep apnea, regardless of symptoms.[37]

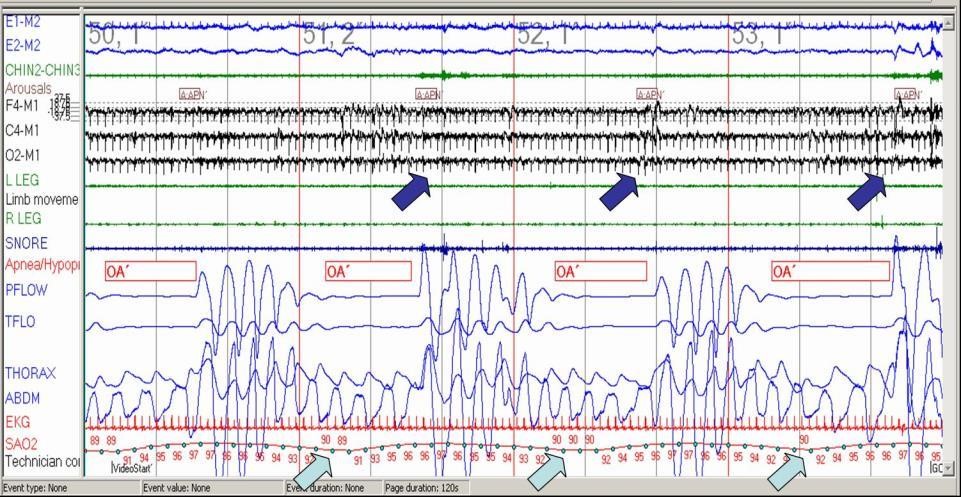

Nighttime in-laboratory level 1 polysomnography (PSG) is considered the gold standard for diagnosing OSA. During the test, patients are monitored using electroencephalogram (EEG) leads, pulse oximetry, temperature and pressure sensors to detect nasal and oral airflow, respiratory impedance plethysmography belts around the chest and abdomen to monitor motion, an electrocardiogram (ECG) lead, and electromyogram sensors to detect muscle contractions in the chin, chest, and legs (see Image. Polysomnography, 120-Second Window Showing Obstructive Sleep Apnea).

Scoring respiratory events in adults relies on 4 primary channels:

- Oronasal thermal sensor

- Nasal air pressure transducer

- Inductance plethysmography (with esophageal manometry or a pressure catheter may be used as alternatives)

- Pulse oximetry [38]

A snoring monitor is a required channel but does not contribute to the scoring of respiratory events.

According to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM), hypopnea is defined by either 1 of 2 criteria:

- A reduction in airflow of at least 30% for more than 10 seconds, accompanied by at least 4% oxygen desaturation (eg, Medicare criteria).

- A reduction in airflow of at least 30% for more than 10 seconds, associated with either at least 3% oxygen desaturation or an arousal from sleep on EEG (recommended AASM criteria).[39]

Scoring apnea requires both of the following criteria to be met:

- A drop in the peak signal excursion by more than or equal to 90% of the pre-event baseline flow.

- A duration of the flow reduction of more than or equal to 10 seconds.

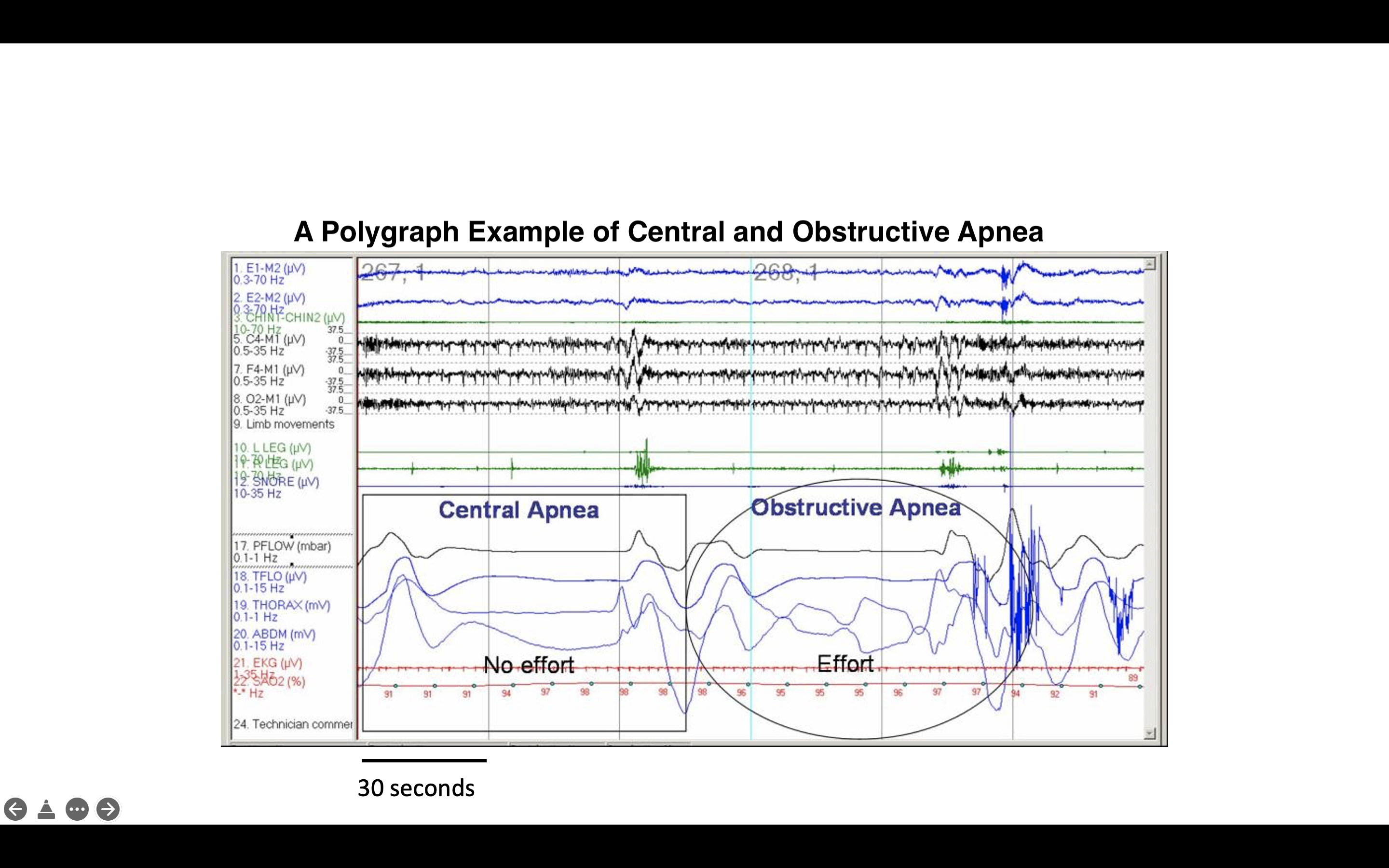

As mentioned below, apneas are usually further classified based on respiratory effort, which is determined by respiratory inductance plethysmography signals (see Image. Polysomnography Showing Central and Obstructive Sleep Apneas).

- Obstructive sleep apnea: If an increased effort is present throughout the entire apnea.

- Central sleep apnea: If no effort is detected throughout the entire apnea.

Mixed apnea is characterized by an absence of effort during the initial portion of the event, followed by the resumption of effort in the latter part of the apnea.

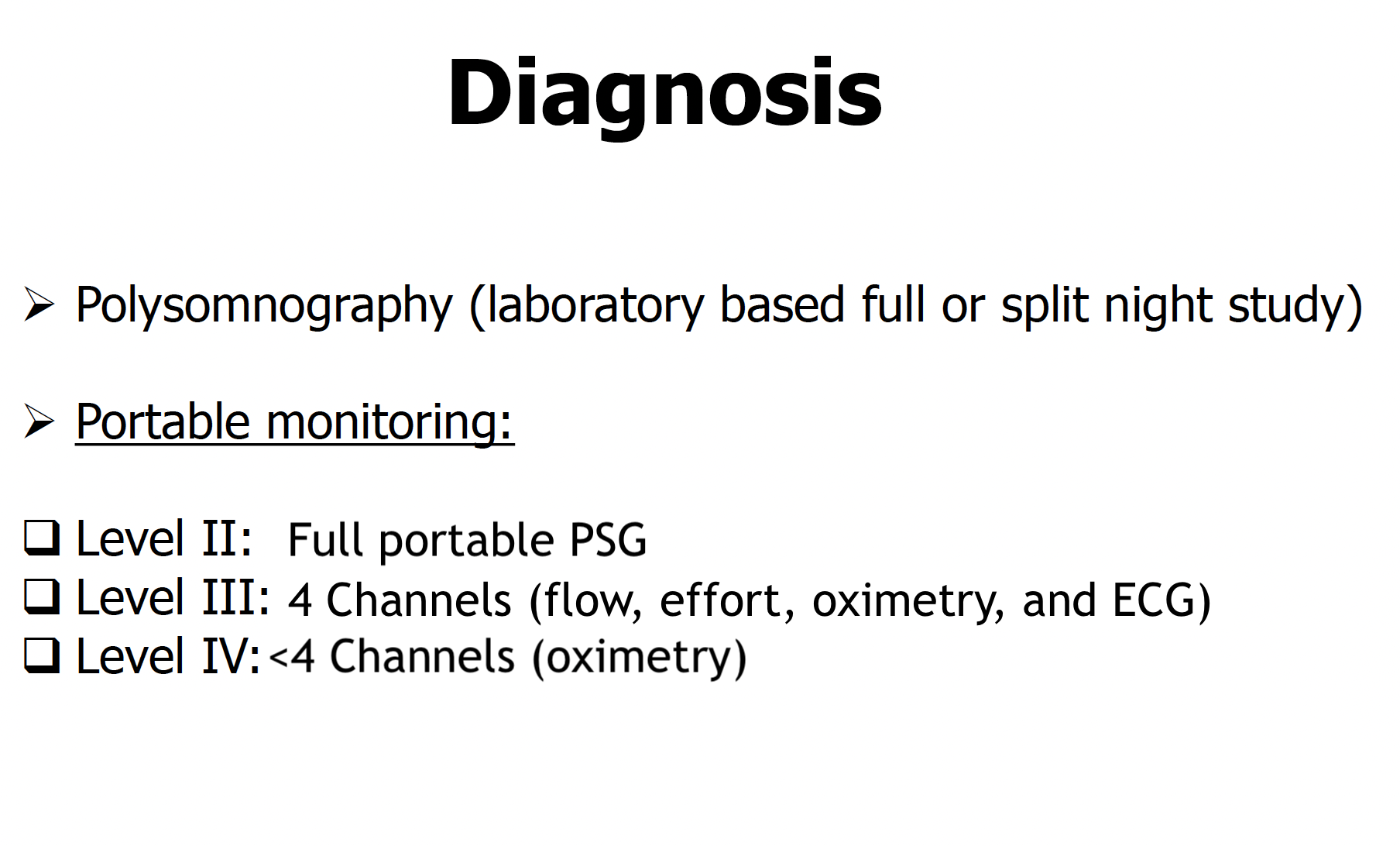

Home sleep tests or portable monitoring have gained popularity due to their accessibility and lower cost. However, portable monitoring should be conducted following specific rules and procedures as outlined by the AASM Unattended Portable Monitoring Task Force guidelines.[40] These guidelines include the following criteria:

- At a minimum, the portable monitoring device must record airflow, respiratory effort, and blood oxygenation.

- The airflow, effort, and oximetric biosensors traditionally used in in-laboratory PSG should also be utilized in portable monitoring.

- Portable monitoring testing must be conducted under the oversight of an AASM-accredited comprehensive sleep medicine program, with established written policies and procedures.

- An experienced sleep technologist or technician must apply the sensors or provide direct patient education on proper sensor application.

- The portable monitoring device must display raw data and allow a trained sleep technologist or technician to manually score or edit automated scoring.

- A board-certified sleep specialist, or an individual meeting the eligibility criteria for the sleep medicine certification examination, must review the raw data from portable monitoring using scoring criteria that align with current AASM standards.[39] Under these specified conditions, portable monitoring may be used for unattended studies in the patient's home.

- A follow-up visit should be scheduled to review test results for all patients undergoing portable monitoring.

- Patients with a high pretest probability of moderate-to-severe OSA who receive negative or technically inadequate portable monitoring results should undergo in-laboratory PSG.

Unattended portable monitoring and home sleep tests are suitable for adults with a high pretest probability of sleep apnea and no significant medical comorbidities, such as advanced congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or neurological disorders. These are level 3 sleep tests, which include pulse oximetry, heart rate monitoring, temperature and pressure sensors to detect nasal and oral airflow, resistance belts around the chest and abdomen to detect motion, and a sensor to monitor body position.

Moderate and severe sleep apnea can be detected using these tests. However, due to the potential underestimation of the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) relative to the total recording time (which may exceed the total sleep time measured in an in-laboratory study), mild sleep apnea may go undiagnosed. In such cases, a repeat in-laboratory study may be necessary. A proposed algorithm for the appropriate use of portable monitoring and in-laboratory PSG is outlined in the Image. Sleep Apnea Testing Modalities.

One of the main limitations of home sleep testing is that most studies use total recording time as the denominator for calculating the AHI, rather than total sleep time, due to the absence of EEG sensors to differentiate sleep from wakefulness. This approach can lead to an underestimation of the AHI by at least 20%.[41]

The AASM recommends using the term respiratory event index (REI) to differentiate the indices of respiratory events generated by a home sleep study (without recorded sleep). The AHI and REI represent the average number of obstructive events per hour, during sleep or recording time, respectively. Although most portable monitoring devices include flow sensors, other technologies, such as peripheral arterial tonometry (PAT), use alternative methods without flow to identify sleep-disordered breathing events. The severity of OSA obtained using PAT devices is referred to as pAHI, which has been reported to provide indices similar to those derived from PSG-based AHI.[42]

The severity of OSA in adults is classified based on AHI, REI, or pAHI as follows:

- Mild: 5 to 15 events per hour

- Moderate: Greater than 15 to 30 events per hour

- Severe: Greater than 30 events per hour

The disease burden in mild OSA is controversial and is primarily based on associated clinical sequelae, such as excessive daytime sleepiness, sleep maintenance insomnia, and cognitive dysfunction.[43]

Recent studies have challenged the traditional definition and scoring criteria of OSA in adults due to its limitations in capturing the pathophysiological impact on individual patients.[19] Various metrics have been proposed to improve the precision in diagnosing OSA,[44] including hypoxic burden, nocturnal heart rate changes, total sleep time with SpO2 less than 90% (TST90), duration of obstructive events, sleep arousal burden, and even genetic factors.[45][46][47][48][49][50][51]

Treatment / Management

Managing OSA requires a multifaceted approach that should be tailored to each patient. While treatment for moderate-to-severe OSA has demonstrated improvements in clinical outcomes,[52] evidence regarding the impact of therapy on mild OSA remains limited or inconsistent, particularly in relation to neurocognition, mood, vehicle accidents, cardiovascular events, stroke, and arrhythmias.[43](A1)

Lifestyle Changes and Treating Underlying Medical Conditions

The importance of weight loss should be emphasized in patients with OSA who are overweight or have obesity.[53][54] Although weight loss is recommended and can often decrease the severity of OSA, it is usually not curative. Patients should be educated about the impact of sleep duration on their health and encouraged to prioritize getting at least 7 to 8 hours of sleep each night.[55] (A1)

Patients should be advised to avoid alcohol, benzodiazepines, opiates, and certain antidepressants, as these may exacerbate their condition. Concomitant nasal obstruction should be addressed with nasal steroids for allergic rhinitis or surgically for nasal valve collapse. For patients with lung or heart conditions, such as asthma or heart failure, optimizing the treatment of these disorders is crucial.

Positional Therapy

OSA that is more pronounced in the supine position can be treated with a positioning device to maintain side-sleeping, which can be an effective option.[56][57]

Positive Airway Pressure Therapy

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is the most effective treatment for adults with OSA.[58] Bilevel PAP is also better tolerated by patients who require higher pressure settings (>15 cm H2O). However, despite the high efficacy of CPAP in eliminating respiratory events, its effectiveness is limited by decreased usage during sleep and poor adherence. Adherence to CPAP remains a significant challenge, as nearly half of patients do not consistently follow treatment after the first month.[59]

The American Thoracic Society recently published a statement on CPAP adherence tracking systems, optimal monitoring strategies, and outcome measures in adults.[60] Standardizing CPAP adherence reports is crucial, not only by tracking the number of hours used (>4 hours per night on >70% of nights) but also by including the amount of mask leak and the residual apnea and hypopnea index. However, what constitutes the optimal adherence goal for OSA treatment remains uncertain. Recent studies have explored the utility of telemedicine adherence interventions, remote CPAP monitoring, and more interactive features with patients and their families, which have been shown to increase CPAP adherence rates.[61][62][63][64](A1)

Several studies have reported conflicting findings when assessing the effect of CPAP therapy on cardiovascular outcomes in patients with OSA.[44] In a recent randomized controlled trial, CPAP use for a minimum of 1 year in patients with acute coronary syndrome and OSA, without excessive daytime sleepiness, did not lower the incidence of cardiovascular events. These events were defined as cardiac-related deaths or one or more of the following outcomes—acute myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, hospital admission for heart failure, and new hospitalizations for unstable angina or transient ischemic attack. However, adherence to CPAP therapy was low (2.78 hours per night), and the follow-up period was insufficient, both of which are significant limitations of the study.[65] (A1)

In another observational cohort study with long-term follow-up, CPAP use was associated with a lower all-cause mortality rate among patients with severe OSA, particularly around years 6 to 7 of follow-up.[66]

In a more recent study, patients with coronary artery disease and OSA who did not experience excessive sleepiness but exhibited greater changes in heart rate showed more benefit from CPAP therapy.[67](A1)

Oral Appliance

For patients who are unable or unwilling to use CPAP, or those who lack reliable access to electricity, custom-fitted and titrated oral appliances or mandibular advancement devices (MAD) can help alleviate airway obstruction by advancing the lower jaw. This approach is typically most effective for candidates with appropriate dentition and mild-to-moderate sleep apnea. In a randomized clinical trial involving 126 patients with moderate-to-severe OSA, the 24-hour mean arterial pressure was similar between CPAP and MAD after the first month of therapy. However, MAD was found to be superior to CPAP in improving quality of life measures.[68] More recently, another randomized clinical trial demonstrated similar long-term improvements for both CPAP and MAD in self-reported neurobehavioral outcomes over a 10-year follow-up.[69](A1)

The AASM and the American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine (AADSM) have developed guidelines for using MAD in patients with OSA.[70] The AASM/AADSM guidelines recommend the following: (A1)

- Oral appliances can be considered as an alternative to no treatment for adult patients with snoring (without OSA) or those with OSA who do not tolerate CPAP therapy or prefer an alternative treatment.

- When a sleep physician prescribes oral appliance therapy for an adult patient with OSA, a qualified dentist should use a custom, titratable appliance.

- A follow-up with a qualified dentist is necessary to assess for dental-related adverse effects after initiating oral appliance therapy in adult patients with OSA.

- Follow-up sleep testing is required to confirm the efficacy of the treatment.

Surgical Treatments

Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) involves the surgical removal of the uvula and tissue from the soft palate to create more space in the oropharynx.[71] This procedure is sometimes performed alongside a tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy. However, the long-term efficacy of UPPP is limited, with fewer than 50% of patients experiencing a significant improvement in the AHI after the first year.[72](A1)

Maxillomandibular advancement (MMA) involves detaching both the upper and lower jaws and surgically advancing them anteriorly to increase space in the oropharynx.[73] This procedure is most effective for patients with retrognathia and tends to be less successful in older patients or those with larger neck circumferences. More recently, drug-induced sleep endoscopy has been used for preoperative planning, helping to identify multiple levels of obstruction in these patients and determining their candidacy for surgical treatments such as MMA or hypoglossal nerve stimulation (HNS).[74] This technique enables surgeons to address nasal, soft palate, and hypopharyngeal obstructions in a single surgery.[75]

A newer treatment option is the implantable HNS, typically implanted unilaterally, although bilateral implantation has been reported recently.[76] This instrument works by stimulating the genioglossus muscle (an upper airway dilator) during apneas, causing tongue protrusion and relieving airway obstruction.[77] HNS effectively reduces the AHI, with a median AHI score at 12 months decreasing by 68%, from 29.3 events per hour to 9.0 events per hour. HNS also improves sleepiness symptoms in patients with moderate-to-severe OSA who are unable to tolerate CPAP treatment.[78] (A1)

Adverse events following HNS, both short- and long-term, are relatively uncommon. In a study, 134 adverse events were reported from 132 patients over 5 years.[79] The most common adverse events reported after HNS are tongue abrasion (11.0%), pain (6.2%), and device malfunction (3% to 6%).[77] (A1)

The eligibility criteria for HNS adopted from the original randomized trial include the following characteristics:

- Adults aged 18 or older

- Moderate-to-severe OSA (AHI between 20 and 50 with <25% central or mixed apneas)

- Inability to tolerate CPAP

- No complete concentric collapse at the palate on drug-induced sleep endoscopy [78] (A1)

Exclusion criteria for HNS include:

- BMI greater than 32.0 kg/m2

- Neuromuscular disease

- Hypoglossal nerve palsy

- Severe restrictive or obstructive pulmonary disease

- Moderate-to-severe pulmonary arterial hypertension

- Severe valvular heart disease

- Heart failure, New York Heart Association class III or IV

- Recent myocardial infarction or severe cardiac arrhythmias (within the past 6 months)

- Persistent uncontrolled hypertension despite medication use

- Active psychiatric disease and coexisting nonrespiratory sleep disorders

In extreme cases, OSA may be treated with a tracheostomy to bypass the oropharyngeal obstruction. This treatment is typically best managed at academic or specialty sleep centers with experience in handling tracheostomy cases. Patients undergoing tracheostomy face numerous challenges, including home care, durable medical equipment needs, and family or partner education on proper tracheostomy management. Additionally, many patients with severe OSA requiring a tracheostomy often have comorbidities that further complicate treatment.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses for OSA include:

- Asthma

- Central sleep apnea

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Depression

- Gastroesophageal reflux

- Hypothyroidism

- Narcolepsy

- Periodic limb movement disorder

Prognosis

The short-term prognosis of OSA with treatment is generally favorable, but the long-term outlook remains uncertain. The primary challenge is poor adherence to CPAP therapy, with nearly 50% of patients discontinuing its use within the first month despite education.[80] Many individuals with OSA have comorbidities or are at an increased risk for adverse cardiac events and stroke. Consequently, individuals who do not adhere to CPAP are at a higher risk for cardiac and cerebral events, as well as increased annual healthcare-related costs.[81][82]

Furthermore, OSA is also associated with pulmonary hypertension, hypercapnia, hypoxemia, and daytime sedation, and these individuals have a high risk of motor vehicle accidents. The overall life expectancy of individuals with OSA is lower than that of the general population. OSA is known to impact cardiac function, especially in individuals with obesity.[83][84] Recent studies have shown that CPAP treatment improves left and right ventricular mechanics in patients with OSA.[85]

Complications

Complications from OSA can include:

- Hypertension

- Myocardial infarction

- Atrial fibrillation

- Congestive heart failure

- Cerebrovascular accident

- Depression

- Sleeplessness-related accidents

Deterrence and Patient Education

Weight loss should be encouraged in patients with OSA. They should be advised to avoid alcohol, benzodiazepines, opiates, and certain antidepressants, as these substances can worsen their condition. Patients should also be educated on the importance of proper sleep hygiene, ensuring sufficient sleep each night, and the risks of driving while drowsy. Adherence to CPAP use should be strongly encouraged, along with proper cleaning and maintenance of the machine to ensure optimal function.

Pearls and Other Issues

An association exists between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and OSA, although a definitive causal relationship has not been established. Up to 47% of patients with PTSD have difficulty maintaining sleep and are known to have a low arousal threshold.[86][87] Patients with both PTSD and OSA experience more severe symptoms of both disorders compared to those with only one condition.[88]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Managing OSA is most effectively achieved through an interprofessional team that includes a sleep specialist, primary care provider, cardiologist, otolaryngologist, dietitian, pulmonologist, neurologist, and nursing staff. Several treatment options are available for OSA, with the primary treatment being CPAP.

Although clinicians oversee overall therapy, nurses and sleep evaluation personnel have a critical role. Nurses are often the first providers to detect therapeutic failure or noncompliance (eg, with CPAP machines) and should prompt clinicians to address the issue and ensure appropriate diagnostic algorithms are followed. An interprofessional care model will lead to the best possible outcomes for OSA patients, particularly given the challenges in managing the condition.

Unfortunately, compliance with CPAP remains low. While some patients may benefit from an oral or nasal device, compliance remains challenging. Surgery is considered a last resort and should only be pursued after a thorough evaluation. Surgery does not cure the disorder, is expensive, and may lead to severe complications. The prognosis for most patients with OSA is guarded. Until weight loss is achieved, most therapies exhibit limited efficacy.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Polysomnography, 120-Second Window Showing Obstructive Sleep Apnea. This polysomnographic recording over a 120-second window displays the electroencephalogram, electrooculogram, electrocardiogram, and chin electromyogram. Note the repetitive obstructive apnea episodes with persistent respiratory effort during the cessation of both nasal pressure flow and thermistor channels, followed by oxygen desaturation (light blue arrows) and arousals (dark blue arrows).

Contributed by A Sankari, MD, PhD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Clinical Assessment of Sleep Apnea. This image illustrates the clinical assessment process for patients with suspected sleep apnea, highlighting key evaluation steps and diagnostic considerations.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BT, bedtime; ED, erectile dysfunction; EDS, excessive daytime sleepiness; ESS, Epworth Sleepiness Scale; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; HEENT, head, ears, eyes, nose, and throat; ISI, insomnia severity index; MP, mandibular plane; OTC, over the counter; RLS, restless legs syndrome; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SOL, sleep onset latency; WT, wake-up time.

Contibuted by A Sankari, MD, PhD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Sleep Apnea Testing Modalities. This image outlines the various sleep apnea testing modalities, ranging from level I (in-laboratory polysomnography) to portable monitoring devices (levels II-IV). According to the AASM guidelines, only level II and III devices are deemed acceptable for diagnosing obstructive sleep apnea.

Contributed by A Sankari, MD, PhD

References

Sankri-Tarbichi AG. Obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome: Etiology and diagnosis. Avicenna journal of medicine. 2012 Jan:2(1):3-8. doi: 10.4103/2231-0770.94803. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23210013]

Mehrtash M, Bakker JP, Ayas N. Predictors of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Adherence in Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Lung. 2019 Apr:197(2):115-121. doi: 10.1007/s00408-018-00193-1. Epub 2019 Jan 7 [PubMed PMID: 30617618]

Esteller E, Carrasco M, Díaz-Herrera MÁ, Vila J, Sampol G, Juvanteny J, Sieira R, Farré A, Vilaseca I. Clinical Practice Guideline recommendations on examination of the upper airway for adults with suspected obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea syndrome. Acta otorrinolaringologica espanola. 2019 Nov-Dec:70(6):364-372. doi: 10.1016/j.otorri.2018.06.008. Epub 2019 Jan 5 [PubMed PMID: 30616837]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCarneiro-Barrera A, Díaz-Román A, Guillén-Riquelme A, Buela-Casal G. Weight loss and lifestyle interventions for obstructive sleep apnoea in adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2019 May:20(5):750-762. doi: 10.1111/obr.12824. Epub 2019 Jan 4 [PubMed PMID: 30609450]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceYeghiazarians Y, Jneid H, Tietjens JR, Redline S, Brown DL, El-Sherif N, Mehra R, Bozkurt B, Ndumele CE, Somers VK. Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021 Jul 20:144(3):e56-e67. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000988. Epub 2021 Jun 21 [PubMed PMID: 34148375]

Schwab RJ, Gupta KB, Gefter WB, Metzger LJ, Hoffman EA, Pack AI. Upper airway and soft tissue anatomy in normal subjects and patients with sleep-disordered breathing. Significance of the lateral pharyngeal walls. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1995 Nov:152(5 Pt 1):1673-89 [PubMed PMID: 7582313]

Isono S, Remmers JE, Tanaka A, Sho Y, Sato J, Nishino T. Anatomy of pharynx in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and in normal subjects. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985). 1997 Apr:82(4):1319-26 [PubMed PMID: 9104871]

Tufik S, Santos-Silva R, Taddei JA, Bittencourt LR. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in the Sao Paulo Epidemiologic Sleep Study. Sleep medicine. 2010 May:11(5):441-6. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.10.005. Epub 2010 Apr 1 [PubMed PMID: 20362502]

Dominguez JE, Habib AS. Obstructive sleep apnea in pregnant women. International anesthesiology clinics. 2022 Apr 1:60(2):59-65. doi: 10.1097/AIA.0000000000000360. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35261345]

Reutrakul S, Mokhlesi B. Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Diabetes: A State of the Art Review. Chest. 2017 Nov:152(5):1070-1086. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.05.009. Epub 2017 May 17 [PubMed PMID: 28527878]

Akset M, Poppe KG, Kleynen P, Bold I, Bruyneel M. Endocrine disorders in obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome: A bidirectional relationship. Clinical endocrinology. 2023 Jan:98(1):3-13. doi: 10.1111/cen.14685. Epub 2022 Feb 19 [PubMed PMID: 35182448]

Yaggi H, Mohsenin V. Obstructive sleep apnoea and stroke. The Lancet. Neurology. 2004 Jun:3(6):333-42 [PubMed PMID: 15157848]

Sankari A, Bascom A, Oomman S, Badr MS. Sleep disordered breathing in chronic spinal cord injury. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2014 Jan 15:10(1):65-72. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.3362. Epub 2014 Jan 15 [PubMed PMID: 24426822]

Kim SJ, Cho SY, Jin DK. Prader-Willi syndrome: an update on obesity and endocrine problems. Annals of pediatric endocrinology & metabolism. 2021 Dec:26(4):227-236. doi: 10.6065/apem.2142164.082. Epub 2021 Dec 31 [PubMed PMID: 34991300]

Hyzer JM, Milczuk HA, Macarthur CJ, King EF, Quintanilla-Dieck L, Lam DJ. Drug-Induced Sleep Endoscopy Findings in Children With Obstructive Sleep Apnea With vs Without Obesity or Down Syndrome. JAMA otolaryngology-- head & neck surgery. 2021 Feb 1:147(2):175-181. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.4548. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33270102]

Sin DD, Fitzgerald F, Parker JD, Newton G, Floras JS, Bradley TD. Risk factors for central and obstructive sleep apnea in 450 men and women with congestive heart failure. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1999 Oct:160(4):1101-6 [PubMed PMID: 10508793]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMoula AI, Parrini I, Tetta C, Lucà F, Parise G, Rao CM, Mauro E, Parise O, Matteucci F, Gulizia MM, La Meir M, Gelsomino S. Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Atrial Fibrillation. Journal of clinical medicine. 2022 Feb 25:11(5):. doi: 10.3390/jcm11051242. Epub 2022 Feb 25 [PubMed PMID: 35268335]

Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. The New England journal of medicine. 1993 Apr 29:328(17):1230-5 [PubMed PMID: 8464434]

Malhotra A, Ayappa I, Ayas N, Collop N, Kirsch D, Mcardle N, Mehra R, Pack AI, Punjabi N, White DP, Gottlieb DJ. Metrics of sleep apnea severity: beyond the apnea-hypopnea index. Sleep. 2021 Jul 9:44(7):. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsab030. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33693939]

Benjafield AV, Ayas NT, Eastwood PR, Heinzer R, Ip MSM, Morrell MJ, Nunez CM, Patel SR, Penzel T, Pépin JL, Peppard PE, Sinha S, Tufik S, Valentine K, Malhotra A. Estimation of the global prevalence and burden of obstructive sleep apnoea: a literature-based analysis. The Lancet. Respiratory medicine. 2019 Aug:7(8):687-698. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30198-5. Epub 2019 Jul 9 [PubMed PMID: 31300334]

Peppard PE, Young T, Barnet JH, Palta M, Hagen EW, Hla KM. Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. American journal of epidemiology. 2013 May 1:177(9):1006-14. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws342. Epub 2013 Apr 14 [PubMed PMID: 23589584]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGottlieb DJ, Punjabi NM. Diagnosis and Management of Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Review. JAMA. 2020 Apr 14:323(14):1389-1400. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3514. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32286648]

Garvey JF, Pengo MF, Drakatos P, Kent BD. Epidemiological aspects of obstructive sleep apnea. Journal of thoracic disease. 2015 May:7(5):920-9. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.04.52. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26101650]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMorrell MJ, Arabi Y, Zahn B, Badr MS. Progressive retropalatal narrowing preceding obstructive apnea. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1998 Dec:158(6):1974-81 [PubMed PMID: 9847295]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSankri-Tarbichi AG, Rowley JA, Badr MS. Expiratory pharyngeal narrowing during central hypocapnic hypopnea. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2009 Feb 15:179(4):313-9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200805-741OC. Epub 2008 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 19201929]

Smith PL, Wise RA, Gold AR, Schwartz AR, Permutt S. Upper airway pressure-flow relationships in obstructive sleep apnea. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985). 1988 Feb:64(2):789-95 [PubMed PMID: 3372436]

Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991 Dec:14(6):540-5 [PubMed PMID: 1798888]

Learmonth YC, Dlugonski D, Pilutti LA, Sandroff BM, Klaren R, Motl RW. Psychometric properties of the Fatigue Severity Scale and the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale. Journal of the neurological sciences. 2013 Aug 15:331(1-2):102-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2013.05.023. Epub 2013 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 23791482]

Russell MB, Kristiansen HA, Kværner KJ. Headache in sleep apnea syndrome: epidemiology and pathophysiology. Cephalalgia : an international journal of headache. 2014 Sep:34(10):752-5. doi: 10.1177/0333102414538551. Epub 2014 Jun 13 [PubMed PMID: 24928423]

Cho YW, Kim KT, Moon HJ, Korostyshevskiy VR, Motamedi GK, Yang KI. Comorbid Insomnia With Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Clinical Characteristics and Risk Factors. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2018 Mar 15:14(3):409-417. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6988. Epub 2018 Mar 15 [PubMed PMID: 29458695]

Maeda T, Fukunaga K, Nagata H, Haraguchi M, Kikuchi E, Miyajima A, Yamasawa W, Shirahama R, Narita M, Betsuyaku T, Asano K, Oya M. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome should be considered as a cause of nocturia in younger patients without other voiding symptoms. Canadian Urological Association journal = Journal de l'Association des urologues du Canada. 2016 Jul-Aug:10(7-8):E241-E245. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.3508. Epub 2016 Jul 12 [PubMed PMID: 28255415]

Subramanian S, Guntupalli B, Murugan T, Bopparaju S, Chanamolu S, Casturi L, Surani S. Gender and ethnic differences in prevalence of self-reported insomnia among patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep & breathing = Schlaf & Atmung. 2011 Dec:15(4):711-5. doi: 10.1007/s11325-010-0426-4. Epub 2010 Oct 16 [PubMed PMID: 20953842]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNagappa M, Liao P, Wong J, Auckley D, Ramachandran SK, Memtsoudis S, Mokhlesi B, Chung F. Validation of the STOP-Bang Questionnaire as a Screening Tool for Obstructive Sleep Apnea among Different Populations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PloS one. 2015:10(12):e0143697. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143697. Epub 2015 Dec 14 [PubMed PMID: 26658438]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSchellenberg JB, Maislin G, Schwab RJ. Physical findings and the risk for obstructive sleep apnea. The importance of oropharyngeal structures. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2000 Aug:162(2 Pt 1):740-8 [PubMed PMID: 10934114]

Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, Weber RP, Arvanitis M, Stine A, Lux L, Harris RP. Screening for Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Adults: Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2017 Jan 24:317(4):415-433. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.19635. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28118460]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceColvin LJ, Collop NA. Commercial Motor Vehicle Driver Obstructive Sleep Apnea Screening and Treatment in the United States: An Update and Recommendation Overview. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2016 Jan:12(1):113-25. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5408. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26094916]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYoung T, Skatrud J, Peppard PE. Risk factors for obstructive sleep apnea in adults. JAMA. 2004 Apr 28:291(16):2013-6 [PubMed PMID: 15113821]

Berry RB, Budhiraja R, Gottlieb DJ, Gozal D, Iber C, Kapur VK, Marcus CL, Mehra R, Parthasarathy S, Quan SF, Redline S, Strohl KP, Davidson Ward SL, Tangredi MM, American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Rules for scoring respiratory events in sleep: update of the 2007 AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events. Deliberations of the Sleep Apnea Definitions Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2012 Oct 15:8(5):597-619. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2172. Epub 2012 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 23066376]

Berry RB, Brooks R, Gamaldo C, Harding SM, Lloyd RM, Quan SF, Troester MT, Vaughn BV. AASM Scoring Manual Updates for 2017 (Version 2.4). Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2017 May 15:13(5):665-666. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6576. Epub 2017 May 15 [PubMed PMID: 28416048]

Collop NA, Anderson WM, Boehlecke B, Claman D, Goldberg R, Gottlieb DJ, Hudgel D, Sateia M, Schwab R, Portable Monitoring Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Clinical guidelines for the use of unattended portable monitors in the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in adult patients. Portable Monitoring Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2007 Dec 15:3(7):737-47 [PubMed PMID: 18198809]

Light MP, Casimire TN, Chua C, Koushyk V, Burschtin OE, Ayappa I, Rapoport DM. Addition of frontal EEG to adult home sleep apnea testing: does a more accurate determination of sleep time make a difference? Sleep & breathing = Schlaf & Atmung. 2018 Dec:22(4):1179-1188. doi: 10.1007/s11325-018-1735-2. Epub 2018 Oct 11 [PubMed PMID: 30311183]

Hedner J, White DP, Malhotra A, Herscovici S, Pittman SD, Zou D, Grote L, Pillar G. Sleep staging based on autonomic signals: a multi-center validation study. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2011 Jun 15:7(3):301-6. doi: 10.5664/JCSM.1078. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21677901]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChowdhuri S, Quan SF, Almeida F, Ayappa I, Batool-Anwar S, Budhiraja R, Cruse PE, Drager LF, Griss B, Marshall N, Patel SR, Patil S, Knight SL, Rowley JA, Slyman A, ATS Ad Hoc Committee on Mild Obstructive Sleep Apnea. An Official American Thoracic Society Research Statement: Impact of Mild Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Adults. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2016 May 1:193(9):e37-54. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201602-0361ST. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27128710]

Yasir M, Pervaiz A, Sankari A. Cardiovascular Outcomes in Sleep-Disordered Breathing: Are We Under-estimating? Frontiers in neurology. 2022:13():801167. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.801167. Epub 2022 Mar 15 [PubMed PMID: 35370882]

Sankari A, Ravelo LA, Maresh S, Aljundi N, Alsabri B, Fawaz S, Hamdon M, Al-Kubaisi G, Hagen E, Badr MS, Peppard P. Longitudinal effect of nocturnal R-R intervals changes on cardiovascular outcome in a community-based cohort. BMJ open. 2019 Jul 17:9(7):e030559. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030559. Epub 2019 Jul 17 [PubMed PMID: 31315880]

Azarbarzin A, Sands SA, Stone KL, Taranto-Montemurro L, Messineo L, Terrill PI, Ancoli-Israel S, Ensrud K, Purcell S, White DP, Redline S, Wellman A. The hypoxic burden of sleep apnoea predicts cardiovascular disease-related mortality: the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study and the Sleep Heart Health Study. European heart journal. 2019 Apr 7:40(14):1149-1157. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy624. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30376054]

Oldenburg O, Wellmann B, Buchholz A, Bitter T, Fox H, Thiem U, Horstkotte D, Wegscheider K. Nocturnal hypoxaemia is associated with increased mortality in stable heart failure patients. European heart journal. 2016 Jun 1:37(21):1695-703. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv624. Epub 2015 Nov 26 [PubMed PMID: 26612581]

Butler MP, Emch JT, Rueschman M, Sands SA, Shea SA, Wellman A, Redline S. Apnea-Hypopnea Event Duration Predicts Mortality in Men and Women in the Sleep Heart Health Study. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2019 Apr 1:199(7):903-912. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201804-0758OC. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30336691]

Shahrbabaki SS, Linz D, Hartmann S, Redline S, Baumert M. Sleep arousal burden is associated with long-term all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in 8001 community-dwelling older men and women. European heart journal. 2021 Jun 1:42(21):2088-2099. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab151. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33876221]

Khalyfa A, Zhang C, Khalyfa AA, Foster GE, Beaudin AE, Andrade J, Hanly PJ, Poulin MJ, Gozal D. Effect on Intermittent Hypoxia on Plasma Exosomal Micro RNA Signature and Endothelial Function in Healthy Adults. Sleep. 2016 Dec 1:39(12):2077-2090. doi: 10.5665/sleep.6302. Epub 2016 Dec 1 [PubMed PMID: 27634792]

Li K, Wei P, Qin Y, Wei Y. MicroRNA expression profiling and bioinformatics analysis of dysregulated microRNAs in obstructive sleep apnea patients. Medicine. 2017 Aug:96(34):e7917. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007917. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28834917]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceda Silva Paulitsch F, Zhang L. Continuous positive airway pressure for adults with obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Sleep medicine. 2019 Feb:54():28-34. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2018.09.030. Epub 2018 Oct 30 [PubMed PMID: 30529774]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNg SSS, Tam WWS, Lee RWW, Chan TO, Yiu K, Yuen BTY, Wong KT, Woo J, Ma RCW, Chan KKP, Ko FWS, Cistulli PA, Hui DS. Effect of Weight Loss and Continuous Positive Airway Pressure on Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Metabolic Profile Stratified by Craniofacial Phenotype: A Randomized Clinical Trial. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2022 Mar 15:205(6):711-720. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202106-1401OC. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34936531]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWong AM, Barnes HN, Joosten SA, Landry SA, Dabscheck E, Mansfield DR, Dharmage SC, Senaratna CV, Edwards BA, Hamilton GS. The effect of surgical weight loss on obstructive sleep apnoea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep medicine reviews. 2018 Dec:42():85-99. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2018.06.001. Epub 2018 Jun 19 [PubMed PMID: 30001806]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAl Lawati NM, Patel SR, Ayas NT. Epidemiology, risk factors, and consequences of obstructive sleep apnea and short sleep duration. Progress in cardiovascular diseases. 2009 Jan-Feb:51(4):285-93. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2008.08.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19110130]

Cerritelli L, Caranti A, Migliorelli A, Bianchi G, Stringa LM, Bonsembiante A, Cammaroto G, Pelucchi S, Vicini C. Sleep position and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA): Do we know how we sleep? A new explorative sleeping questionnaire. Sleep & breathing = Schlaf & Atmung. 2022 Dec:26(4):1973-1981. doi: 10.1007/s11325-022-02576-4. Epub 2022 Feb 7 [PubMed PMID: 35129756]

Jo JH, Kim SH, Jang JH, Park JW, Chung JW. Comparison of polysomnographic and cephalometric parameters based on positional and rapid eye movement sleep dependency in obstructive sleep apnea. Scientific reports. 2022 Jun 14:12(1):9828. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-13850-6. Epub 2022 Jun 14 [PubMed PMID: 35701572]

Ravesloot MJ, de Vries N. Reliable calculation of the efficacy of non-surgical and surgical treatment of obstructive sleep apnea revisited. Sleep. 2011 Jan 1:34(1):105-10 [PubMed PMID: 21203364]

Xanthopoulos MS, Kim JY, Blechner M, Chang MY, Menello MK, Brown C, Matthews E, Weaver TE, Shults J, Marcus CL. Self-Efficacy and Short-Term Adherence to Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Treatment in Children. Sleep. 2017 Jul 1:40(7):. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsx096. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28541508]

Schwab RJ, Badr SM, Epstein LJ, Gay PC, Gozal D, Kohler M, Lévy P, Malhotra A, Phillips BA, Rosen IM, Strohl KP, Strollo PJ, Weaver EM, Weaver TE, ATS Subcommittee on CPAP Adherence Tracking Systems. An official American Thoracic Society statement: continuous positive airway pressure adherence tracking systems. The optimal monitoring strategies and outcome measures in adults. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2013 Sep 1:188(5):613-20. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201307-1282ST. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23992588]

Fox N, Hirsch-Allen AJ, Goodfellow E, Wenner J, Fleetham J, Ryan CF, Kwiatkowska M, Ayas NT. The impact of a telemedicine monitoring system on positive airway pressure adherence in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep. 2012 Apr 1:35(4):477-81. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1728. Epub 2012 Apr 1 [PubMed PMID: 22467985]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBakker JP, Weaver TE, Parthasarathy S, Aloia MS. Adherence to CPAP: What Should We Be Aiming For, and How Can We Get There? Chest. 2019 Jun:155(6):1272-1287. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.01.012. Epub 2019 Jan 23 [PubMed PMID: 30684472]

Khan NNS, Todem D, Bottu S, Badr MS, Olomu A. Impact of patient and family engagement in improving continuous positive airway pressure adherence in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2022 Jan 1:18(1):181-191. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.9534. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34270409]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceThong BKS, Loh GXY, Lim JJ, Lee CJL, Ting SN, Li HP, Li QY. Telehealth Technology Application in Enhancing Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Adherence in Obstructive Sleep Apnea Patients: A Review of Current Evidence. Frontiers in medicine. 2022:9():877765. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.877765. Epub 2022 May 3 [PubMed PMID: 35592853]

Sánchez-de-la-Torre M, Sánchez-de-la-Torre A, Bertran S, Abad J, Duran-Cantolla J, Cabriada V, Mediano O, Masdeu MJ, Alonso ML, Masa JF, Barceló A, de la Peña M, Mayos M, Coloma R, Montserrat JM, Chiner E, Perelló S, Rubinós G, Mínguez O, Pascual L, Cortijo A, Martínez D, Aldomà A, Dalmases M, McEvoy RD, Barbé F, Spanish Sleep Network. Effect of obstructive sleep apnoea and its treatment with continuous positive airway pressure on the prevalence of cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ISAACC study): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. Respiratory medicine. 2020 Apr:8(4):359-367. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30271-1. Epub 2019 Dec 12 [PubMed PMID: 31839558]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLisan Q, Van Sloten T, Marques Vidal P, Haba Rubio J, Heinzer R, Empana JP. Association of Positive Airway Pressure Prescription With Mortality in Patients With Obesity and Severe Obstructive Sleep Apnea: The Sleep Heart Health Study. JAMA otolaryngology-- head & neck surgery. 2019 Jun 1:145(6):509-515. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.0281. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30973594]

Azarbarzin A, Zinchuk A, Wellman A, Labarca G, Vena D, Gell L, Messineo L, White DP, Gottlieb DJ, Redline S, Peker Y, Sands SA. Cardiovascular Benefit of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure in Adults with Coronary Artery Disease and Obstructive Sleep Apnea without Excessive Sleepiness. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2022 Sep 15:206(6):767-774. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202111-2608OC. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35579605]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePhillips CL, Grunstein RR, Darendeliler MA, Mihailidou AS, Srinivasan VK, Yee BJ, Marks GB, Cistulli PA. Health outcomes of continuous positive airway pressure versus oral appliance treatment for obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized controlled trial. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2013 Apr 15:187(8):879-87. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201212-2223OC. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23413266]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceUniken Venema JAM, Doff MHJ, Joffe-Sokolova D, Wijkstra PJ, van der Hoeven JH, Stegenga B, Hoekema A. Long-term obstructive sleep apnea therapy: a 10-year follow-up of mandibular advancement device and continuous positive airway pressure. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2020 Mar 15:16(3):353-359. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.8204. Epub 2020 Jan 14 [PubMed PMID: 31992403]

Ramar K, Dort LC, Katz SG, Lettieri CJ, Harrod CG, Thomas SM, Chervin RD. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Snoring with Oral Appliance Therapy: An Update for 2015. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2015 Jul 15:11(7):773-827. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.4858. Epub 2015 Jul 15 [PubMed PMID: 26094920]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceManiaci A, Di Luca M, Lechien JR, Iannella G, Grillo C, Grillo CM, Merlino F, Calvo-Henriquez C, De Vito A, Magliulo G, Pace A, Vicini C, Cocuzza S, Bannò V, Pollicina I, Stilo G, Bianchi A, La Mantia I. Lateral pharyngoplasty vs. traditional uvulopalatopharyngoplasty for patients with OSA: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep & breathing = Schlaf & Atmung. 2022 Dec:26(4):1539-1550. doi: 10.1007/s11325-021-02520-y. Epub 2022 Jan 3 [PubMed PMID: 34978022]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHe M, Yin G, Zhan S, Xu J, Cao X, Li J, Ye J. Long-term Efficacy of Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty among Adult Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2019 Sep:161(3):401-411. doi: 10.1177/0194599819840356. Epub 2019 Jun 11 [PubMed PMID: 31184261]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMartin MJ, Khanna A, Srinivasan D, Sovani MP. Patient-reported outcome measures following maxillomandibular advancement surgery in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. The British journal of oral & maxillofacial surgery. 2022 Sep:60(7):963-968. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2022.03.006. Epub 2022 Mar 22 [PubMed PMID: 35667944]

Zhou N, Ho JTF, de Vries N, Bosschieter PFN, Ravesloot MJL, de Lange J. Evaluation of drug-induced sleep endoscopy as a tool for selecting patients with obstructive sleep apnea for maxillomandibular advancement. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2022 Apr 1:18(4):1073-1081. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.9802. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34877928]

Huang Z, Bosschieter PFN, Aarab G, van Selms MKA, Vanhommerig JW, Hilgevoord AAJ, Lobbezoo F, de Vries N. Predicting upper airway collapse sites found in drug-induced sleep endoscopy from clinical data and snoring sounds in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a prospective clinical study. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2022 Sep 1:18(9):2119-2131. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.9998. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35459443]

Lewis R, Pételle B, Campbell MC, MacKay S, Palme C, Raux G, Sommer JU, Maurer JT. Implantation of the nyxoah bilateral hypoglossal nerve stimulator for obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope investigative otolaryngology. 2019 Dec:4(6):703-707. doi: 10.1002/lio2.312. Epub 2019 Nov 22 [PubMed PMID: 31890891]

Kompelli AR, Ni JS, Nguyen SA, Lentsch EJ, Neskey DM, Meyer TA. The outcomes of hypoglossal nerve stimulation in the management of OSA: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World journal of otorhinolaryngology - head and neck surgery. 2019 Mar:5(1):41-48. doi: 10.1016/j.wjorl.2018.04.006. Epub 2018 Sep 25 [PubMed PMID: 30775701]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceStrollo PJ Jr, Soose RJ, Maurer JT, de Vries N, Cornelius J, Froymovich O, Hanson RD, Padhya TA, Steward DL, Gillespie MB, Woodson BT, Van de Heyning PH, Goetting MG, Vanderveken OM, Feldman N, Knaack L, Strohl KP, STAR Trial Group. Upper-airway stimulation for obstructive sleep apnea. The New England journal of medicine. 2014 Jan 9:370(2):139-49. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308659. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24401051]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBellamkonda N, Shiba T, Mendelsohn AH. Adverse Events in Hypoglossal Nerve Stimulator Implantation: 5-Year Analysis of the FDA MAUDE Database. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2021 Feb:164(2):443-447. doi: 10.1177/0194599820960069. Epub 2020 Sep 22 [PubMed PMID: 32957866]

Guralnick AS, Balachandran JS, Szutenbach S, Adley K, Emami L, Mohammadi M, Farnan JM, Arora VM, Mokhlesi B. Educational video to improve CPAP use in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea at risk for poor adherence: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2017 Dec:72(12):1132-1139. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210106. Epub 2017 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 28667231]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMarshall NS, Wong KK, Cullen SR, Knuiman MW, Grunstein RR. Sleep apnea and 20-year follow-up for all-cause mortality, stroke, and cancer incidence and mortality in the Busselton Health Study cohort. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2014 Apr 15:10(4):355-62. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.3600. Epub 2014 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 24733978]

Bock JM, Needham KA, Gregory DA, Ekono MM, Wickwire EM, Somers VK, Lerman A. Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Adherence and Treatment Cost in Patients With Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Cardiovascular Disease. Mayo Clinic proceedings. Innovations, quality & outcomes. 2022 Apr:6(2):166-175. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2022.01.002. Epub 2022 Apr 4 [PubMed PMID: 35399584]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAlkatib S, Sankri-Tarbichi AG, Badr MS. The impact of obesity on cardiac dysfunction in patients with sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep & breathing = Schlaf & Atmung. 2014 Mar:18(1):137-42. doi: 10.1007/s11325-013-0861-0. Epub 2013 May 15 [PubMed PMID: 23673872]

Saeed S, Romarheim A, Solheim E, Bjorvatn B, Lehmann S. Cardiovascular remodeling in obstructive sleep apnea: focus on arterial stiffness, left ventricular geometry and atrial fibrillation. Expert review of cardiovascular therapy. 2022 Jun:20(6):455-464. doi: 10.1080/14779072.2022.2081547. Epub 2022 Jun 8 [PubMed PMID: 35673889]

Tadic M, Gherbesi E, Faggiano A, Sala C, Carugo S, Cuspidi C. The impact of continuous positive airway pressure on cardiac mechanics: Findings from a meta-analysis of echocardiographic studies. Journal of clinical hypertension (Greenwich, Conn.). 2022 Jul:24(7):795-803. doi: 10.1111/jch.14488. Epub 2022 Jun 13 [PubMed PMID: 35695237]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceOhayon MM, Shapiro CM. Sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders associated with posttraumatic stress disorder in the general population. Comprehensive psychiatry. 2000 Nov-Dec:41(6):469-78 [PubMed PMID: 11086154]

El-Solh AA, Lawson Y, Wilding GE. Impact of low arousal threshold on treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder. Sleep & breathing = Schlaf & Atmung. 2021 Jun:25(2):597-604. doi: 10.1007/s11325-020-02106-0. Epub 2020 Jul 10 [PubMed PMID: 32458377]

Lettieri CJ, Williams SG, Collen JF. OSA Syndrome and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Clinical Outcomes and Impact of Positive Airway Pressure Therapy. Chest. 2016 Feb:149(2):483-490. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-0693. Epub 2016 Jan 1 [PubMed PMID: 26291560]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence