Introduction

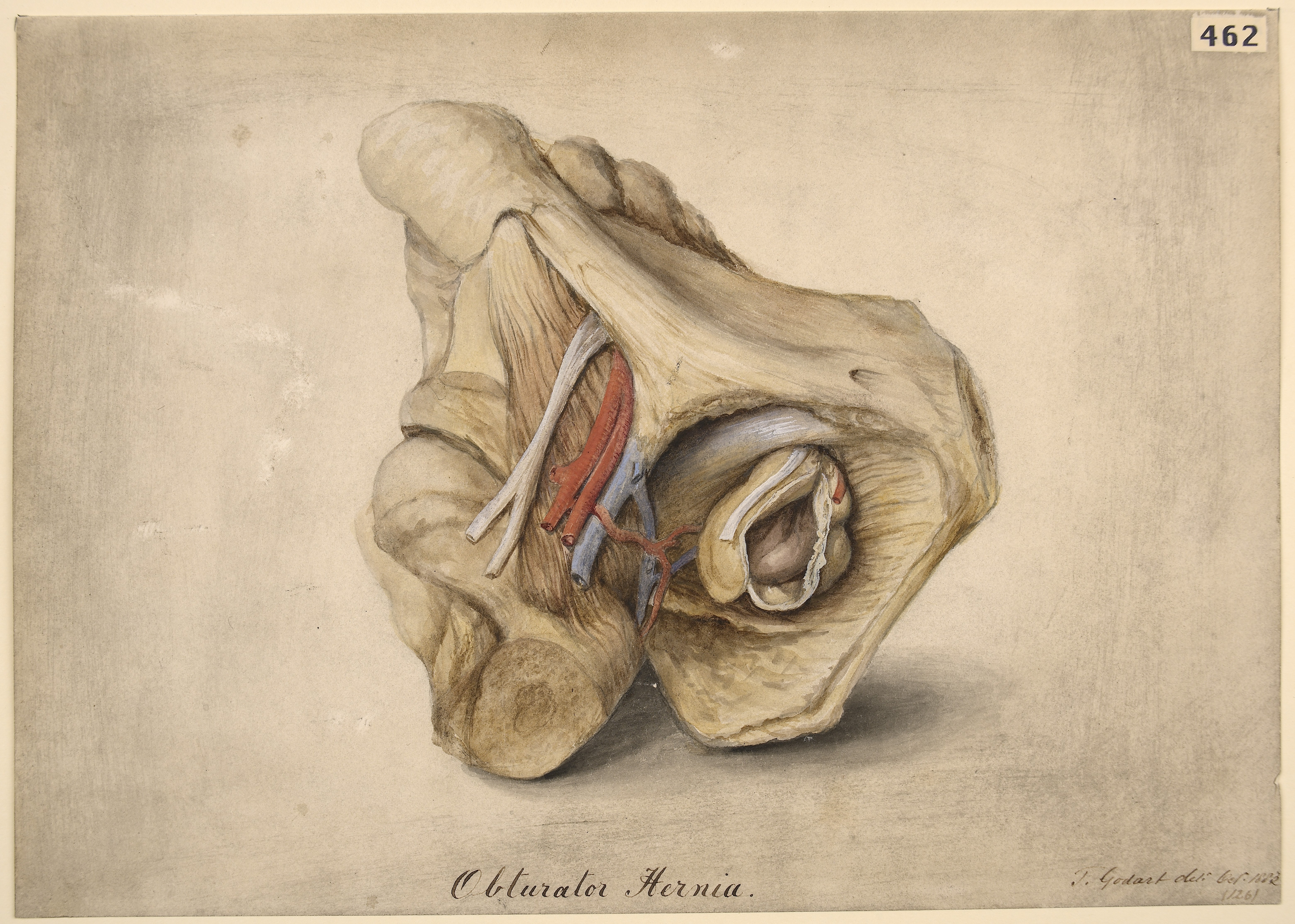

The obturator hernia was first described by Arnaud de Ronsil in 1724. More than 100 years later, Henry Obre performed the first successful obturator hernia repair in 1851. Migration of intra-abdominal contents through the obturator foramen constitutes an obturator hernia (see Image. Obturator Hernia). The hernia sac most often contains small bowel, though other intra-abdominal structures may also be involved, including preperitoneal fat, omentum, and large bowel. (Source: Conti et al, 2022) Obturator hernias are rare, accounting for approximately 0.05 to 1.5% of all hernias.[1][2]

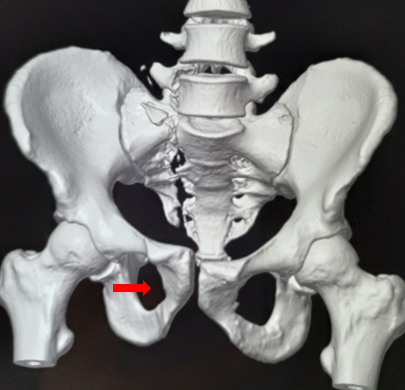

The obturator foramen is a large pelvic aperture bounded by the ischium and pubic bone (see Image. Obturator Foramen). In adults, this opening may measure 2 to 3 cm in length and 0.5 to 1 cm in width. A thin, fibrous membrane spans the bony margins of the foramen. The internal and external surfaces of this orifice serve as attachment sites for the obturator internus and externus muscles, respectively.

The internal iliac artery gives rise to the obturator artery, which divides into medial and lateral branches that encircle the foramen. The obturator nerve, artery, and vein pass from the pelvis into the thigh through the obturator canal, located at the superior aspect of the foramen. The obturator nerve lies most cranially within this neurovascular bundle and divides into anterior and posterior branches upon exiting the canal. Unlike the rest of the obturator foramen, the obturator canal is not covered by a fibrous membrane.

Female individuals have larger, more triangular obturator foramina than male individuals. Herniation of structures through the obturator foramen occurs more frequently in women, particularly those of advanced age and low body mass, due to anatomic predisposition. The sigmoid colon generally overlies the left obturator foramen. Thus, obturator hernias are more common on the right in both sexes.[3]

Diagnosis is often challenging, as presenting signs and symptoms are frequently nonspecific.[4] Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion, especially in older patients with low body mass, and promptly obtain computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis. Treatment is surgical, employing open or minimally invasive techniques.[5][6] Morbidity and mortality rates depend on the presence of complications and the timeliness of surgical intervention.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Formation of an obturator hernia is facilitated by anatomic factors that permit invagination of abdominal contents through the obturator foramen. Increasing age, female sex, multiparity, rapid weight loss, and malnutrition with emaciation weaken the pelvic floor and reduce the soft tissue that normally overlies the foramen.[7] Conditions that increase intra-abdominal pressure, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ascites, constipation, and chronic cough, further elevate the risk. The nature and severity of complications depend on the structures contained within the hernia sac and whether strangulation is present. Bowel involvement is most common, although the ovary, fallopian tube, ureter, and soft tissues may also protrude through the foramen.[8]

Epidemiology

Obturator hernias occur most frequently in women of advanced age and low body mass due to anatomic predisposition, including wide obturator foramina and weaker pelvic floor musculature.[9][10] The condition is sometimes referred to in the literature as the “little old lady’s hernia.” Obturator hernias account for approximately 0.05% to 2% of all hernias, with bilateral involvement reported in about 25% of cases. Right-sided obturator hernias are more common than left-sided ones, likely because the sigmoid colon overlies and shields the left obturator foramen.[11][12][13]

History and Physical

Patients with symptomatic obturator hernias most often present directly to the emergency department. Reported manifestations are typically nonspecific and may include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, pelvic pain, thigh pain, constipation, or hip pain radiating into the ipsilateral lower extremity, mimicking radiculopathy. Some patients describe prior episodes of similar symptoms that resolved without intervention.[14]

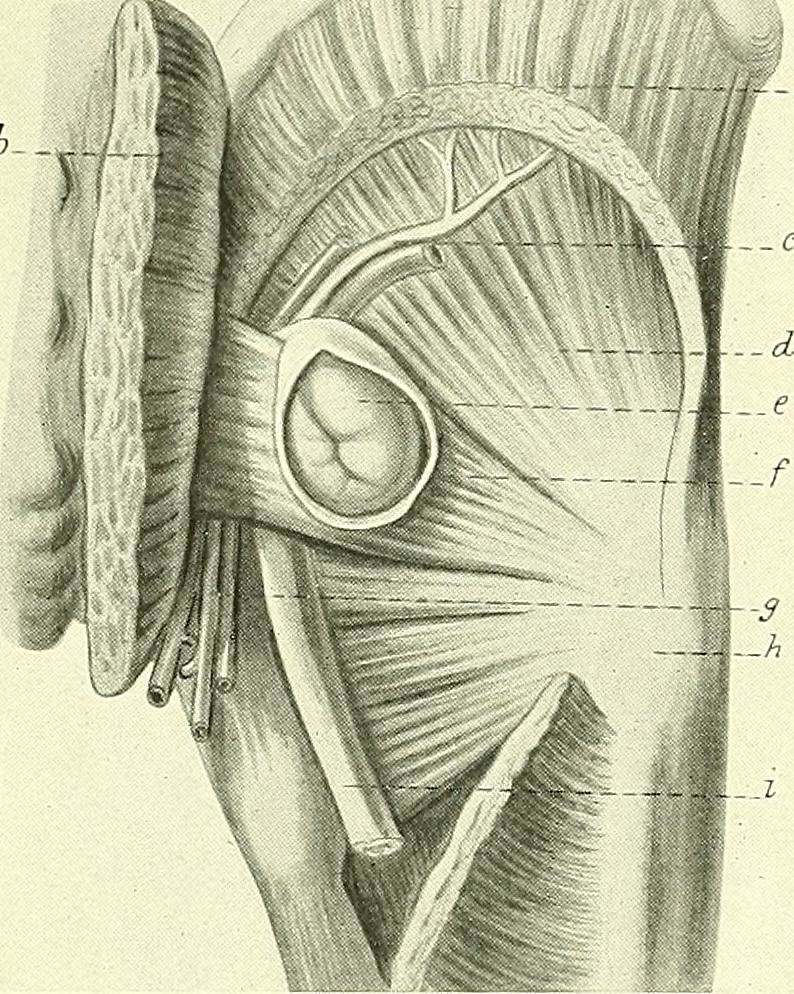

Affected individuals often appear uncomfortable on examination. Abdominal or pelvic tenderness and abdominal distension may be present, and signs of peritoneal irritation can occur in cases of bowel necrosis or perforation. The hernia sac is generally not palpable because of the deep location of the obturator foramen (see Image. Obturator Hernia Contents).[15][16]

Two physical examination signs are described, but neither is sufficiently sensitive nor specific to confirm or exclude the diagnosis. The Howship-Romberg sign is characterized by pain on adduction, extension, and medial rotation of the thigh caused by compression of the cutaneous branch of the obturator nerve by the hernia sac. The sensitivity of this finding is approximately 50%. The Hannington-Kiff sign is marked by loss of the thigh adductor reflex with preservation of the patellar reflex due to obturator nerve compression. This sign is elicited by placing a finger on the adductors 5 cm above the knee and percussing the finger with a tendon hammer. Muscle contraction indicates an intact reflex. The Hannington-Kiff sign is more specific than the Howship-Romberg sign but is technically more difficult and operator-dependent.[17][18]

Evaluation

Patients with a suspected obturator hernia should undergo a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with or without intravenous contrast.[19] CT can delineate the size and contents of the hernia sac and identify complications, such as bowel obstruction, necrosis, or perforation. Reported diagnostic accuracy is as high as 90%.[20] However, in some patients later diagnosed with obturator hernia during surgery, CT imaging either failed to identify the pathology or did not adequately characterize its features.[21] Surgical consultation for possible exploration is warranted when clinical suspicion persists despite the lack of evidence of abnormality on CT.

Pertinent laboratory evaluation includes complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, blood typing and screening, and serum lactate measurement. Leukocytosis may occur in the setting of bowel obstruction, perforation, peritonitis, or as a stress response. Electrolyte abnormalities may result from vomiting, diarrhea, or volume depletion. Patients with ureteral herniation and obstruction may exhibit elevated blood urea nitrogen and creatinine. Blood typing and screening are useful for preoperative preparation. Elevated lactate may indicate bowel ischemia or necrosis.

Treatment / Management

Surgical Intervention

Surgery is required for the treatment of an obturator hernia. Surgical consultation should be sought emergently upon identification of the condition on imaging. In cases where the hernia contains only the ureter, repair may be delayed until renal function improves.

No universal consensus has been established regarding the optimal surgical approach. However, the methods most commonly employed to treat obturator hernias are midline laparotomy or laparoscopy, with minimally invasive robotic techniques becoming increasingly available.[22][23] Retropubic, inguinal, and femoral approaches have also been described.[24] Laparoscopic repair is preferred when feasible because it is associated with lower intraoperative blood loss, less postoperative pain, reduced risk of infection and ileus, and shorter hospitalization compared with laparotomy. Conversion to laparotomy may be undertaken intraoperatively if required.(B2)

The most frequently described laparoscopic techniques are transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) and total extraperitoneal (TEP) procedures. Most case reports describe reduction via the transabdominal preperitoneal approach, which permits direct visualization of the hernia contents and assessment of bowel viability.[25][26] If bowel resection is necessary, the surgeon may continue with this laparoscopic approach or switch to open surgery, depending on intraoperative findings. The total extraperitoneal technique is reserved for cases without suspected strangulation or necrosis and allows simultaneous repair of the inguinal and obturator spaces without entering the peritoneal cavity.(B3)

Several methods exist for closure of the obturator foramen to prevent recurrence. Defects smaller than 1 cm may be repaired directly with sutures, although suture repair may carry a higher risk of recurrence than mesh repair.

Mesh repair is reasonable if the bowel is viable or the defect is too large for primary closure. Large hernia defects may also be repaired with other tissues, such as a peritoneal or periosteal patch, omentum, or musculoaponeurotic flap, depending on surgeon preference.

Exploration of the opposite obturator foramen may be warranted if CT does not adequately exclude contralateral involvement, as some patients have bilateral obturator hernias. Concomitant inguinal or femoral hernias may also be present. Prophylactic repair of these incidental hernias is sometimes performed when detected intraoperatively to prevent future complications.[27]

Manual Reduction

Obturator hernias are generally not palpable and cannot be reduced manually, although rare successful reductions have been reported. Manual reduction is technically challenging, does not allow assessment of bowel viability, and carries a substantial risk of failure or recurrence. Cases of ultrasound-guided manual reduction followed by surgical repair have also been described.[28]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, or constipation is extensive. However, compared to younger individuals, older adults may not demonstrate typical symptoms or examination findings due to altered inflammatory and pain responses, putting this patient group at greater risk for obturator hernias. Important considerations include gastrointestinal disorders such as small or large bowel obstruction, ileus, intestinal perforation, gastritis, gastroenteritis, infectious or inflammatory colitis, volvulus, appendicitis, abdominal wall or inguinal hernia, diaphragmatic hernia, pancreatitis, biliary colic or cholecystitis, and hepatitis.

Cardiac causes, such as acute coronary syndrome, may obscure the manifestations of a surgical abdomen. Genitourinary conditions to consider include ovarian or testicular torsion and urinary tract infection or pyelonephritis. Vascular disorders, such as mesenteric ischemia, abdominal aortic aneurysm, and aortic dissection, should be differentiated from an obturator hernia. Metabolic disturbances that must be ruled out include diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar hyperglycemic nonketotic syndrome. Nonspecific causes of abdominal symptoms include medication adverse effects or withdrawal.

Prognosis

Historically, an obturator hernia diagnosis carried a substantial risk of morbidity and mortality. Improved outcomes in recent decades are likely attributable to increased clinical awareness, broader access to advanced CT imaging, and advances in surgical techniques.

Patients who undergo bowel resection may develop complications frequently associated with this procedure, such as ostomy dysfunction, anastomotic leaks, and intra-abdominal infection. Mesh placement for hernia repair carries potential risks of future mesh infection and migration. As with other major abdominal surgeries and hospitalizations, patients who undergo operative treatment for obturator hernia are also at risk for severe pain, infection, venous thromboembolism, skin breakdown, and deconditioning.

Reported mortality rates vary widely, from 12% to 70%. The persistently high figures are attributed to delays in diagnosis and treatment due to the nonspecific presentation of the condition, as well as the advanced age, frailty, and comorbidities common in the predisposed population.[29][30][31][32][33]

Complications

Protrusion of abdominal or pelvic contents through the obturator foramen may lead to obstruction or incarceration of viscera and occlusion of blood vessels. Bowel entrapment may cause obstruction, strangulation, necrosis, or perforation with subsequent peritonitis and sepsis. Ureteral herniation can lead to hydronephrosis and renal dysfunction. Obturator nerve compression may produce pain, paresthesia, or weakness in this neural structure's sensory and motor distribution.

Obturator hernias carry a small risk of recurrence, whether repaired with sutures or mesh. Patients with symptoms suggestive of this condition should be evaluated for recurrence even after prior repair. Herniation on the contralateral side may also occur.

The incidence of complications following obturator hernia repair is approximately 11%. The sequelae resemble those seen in other major abdominal surgeries, including wound infection, wound dehiscence, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, sepsis, and anastomotic leak. Mesh placement may result in infection or migration. Intraoperative and postoperative risks depend on the surgical approach, the extent of tissue necrosis, the presence of intestinal perforation, and preexisting comorbidities.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Postoperative care should follow local protocols for hernia repair, bowel resection, and surgical interventions performed for any associated complications. Most patients are admitted after surgery and require analgesia, bowel rest, and wound care. Mobilization and diet advancement should begin as soon as tolerated.

Physical and occupational therapy, as well as nutrition consultation, are beneficial before hospital discharge, given that patients with obturator hernias are typically of advanced age and frail at baseline. Discharge to a skilled nursing facility may be necessary when ongoing care needs are anticipated. Outpatient follow-up with the surgical team should be arranged according to local protocols.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Prevention of obturator hernia is generally impossible, except through modification of risk factors for pelvic laxity and increased abdominal pressure. Addressing malnutrition and cachexia may help restore physiologic intra-abdominal fat pads that support the obturator foramen. Management of chronic ascites, persistent coughing, and constipation may reduce sustained increases in intra-abdominal pressure.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Prompt diagnosis and treatment require an interprofessional, team-based approach. An obturator hernia rarely presents asymptomatically. Thus, patients typically arrive at the emergency department with uncomfortable symptoms related to entrapment, obstruction, or strangulation of structures in the hernia sac. Nursing staff are essential for administering pain medication, fluids, and antibiotics intravenously, alongside wound care, before and after surgical intervention. These healthcare professionals may also insert a nasogastric tube for bowel decompression in cases of gut obstruction. Emergency department providers must communicate the diagnosis, associated complications, and anticipated treatment plan with the interprofessional team to minimize delays to definitive surgical intervention.

Imaging serves as the primary diagnostic tool in most cases, making radiologists critical for identifying and communicating the presence of an obturator hernia to the patient’s primary provider. An obturator hernia can be difficult to detect on imaging. Consequently, radiologists must examine CT scans carefully for the presence of this condition. Communicating concern for an obturator hernia in the CT order can prompt targeted assessment by the radiologist.

Surgeons and interprofessional surgical teams treat patients perioperatively and coordinate optimal postsurgical care, which may be provided in the intensive care unit or a general medical ward, depending on the severity of complications and underlying comorbidities. Nursing staff, pharmacists, technicians, and occupational and physical therapists in these units must ensure adequate analgesia, nutrition, and rehabilitation in preparation for hospital discharge. When a stoma is created, specialized nurses, along with general nursing staff, should closely monitor the site and its output, providing patient education on stoma care after discharge as needed.

Case management coordinates a safe discharge from the hospital, either to home or a skilled nursing facility. Many patients with an obturator hernia are advanced in age and frail, often with significant care needs after discharge. Access to medications, durable medical equipment, and adequate nursing care after discharge is essential for optimal recovery.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Obturator Hernia. This anatomical illustration shows protrusion of abdominal contents through the obturator foramen, with adjacent vessels and surrounding pelvic structures.

St Bartholomew's Hospital Archives & Museum. From the Wellcome Collection. https://wellcomecollection.org/works/gcenude2. 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Chung CC, Mok CO, Kwong KH, Ng EK, Lau WY, Li AK. Obturator hernia revisited: a review of 12 cases in 7 years. Journal of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. 1997 Apr:42(2):82-4 [PubMed PMID: 9114674]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLi Z, Gu C, Wei M, Yuan X, Wang Z. Diagnosis and treatment of obturator hernia: retrospective analysis of 86 clinical cases at a single institution. BMC surgery. 2021 Mar 9:21(1):124. doi: 10.1186/s12893-021-01125-2. Epub 2021 Mar 9 [PubMed PMID: 33750366]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDelgado A, Bhuller SB, Phan P, Weaver J. Rare case of obturator hernia: Surgical anatomy, planning, and considerations. SAGE open medical case reports. 2022:10():2050313X221081371. doi: 10.1177/2050313X221081371. Epub 2022 Mar 22 [PubMed PMID: 35341101]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGilbert JD, Byard RW. Obturator hernia and the elderly. Forensic science, medicine, and pathology. 2019 Sep:15(3):491-493. doi: 10.1007/s12024-018-0046-z. Epub 2018 Nov 5 [PubMed PMID: 30397870]

Shapiro K, Patel S, Choy C, Chaudry G, Khalil S, Ferzli G. Totally extraperitoneal repair of obturator hernia. Surgical endoscopy. 2004 Jun:18(6):954-6 [PubMed PMID: 15095078]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWu JM, Lin HF, Chen KH, Tseng LM, Huang SH. Laparoscopic preperitoneal mesh repair of incarcerated obturator hernia and contralateral direct inguinal hernia. Journal of laparoendoscopic & advanced surgical techniques. Part A. 2006 Dec:16(6):616-9 [PubMed PMID: 17243881]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDhital B, Gul-E-Noor F, Downing KT, Hirsch S, Boutis GS. Pregnancy-Induced Dynamical and Structural Changes of Reproductive Tract Collagen. Biophysical journal. 2016 Jul 12:111(1):57-68. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.05.049. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27410734]

Neureiter J, Goerl T, Tolla-Jensen C, Wiessner R. Laparoscopic Repair of Ureteral Obturator Hernia Using Extended TAPP Technique: A Case Report. The American journal of case reports. 2025 Mar 21:26():e948017. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.948017. Epub 2025 Mar 21 [PubMed PMID: 40114368]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMantoo SK, Mak K, Tan TJ. Obturator hernia: diagnosis and treatment in the modern era. Singapore medical journal. 2009 Sep:50(9):866-70 [PubMed PMID: 19787172]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHolm MA, Baker JJ, Andresen K, Fonnes S, Rosenberg J. Epidemiology and surgical management of 184 obturator hernias: a nationwide registry-based cohort study. Hernia : the journal of hernias and abdominal wall surgery. 2023 Dec:27(6):1451-1459. doi: 10.1007/s10029-023-02891-z. Epub 2023 Sep 25 [PubMed PMID: 37747656]

Chowbey PK, Bandyopadhyay SK, Khullar R, Soni V, Baijal M, Wadhwa A, Sharma A. Endoscopic totally extraperitoneal repair for occult bilateral obturator hernias and multiple groin hernias. Journal of laparoendoscopic & advanced surgical techniques. Part A. 2004 Oct:14(5):313-6 [PubMed PMID: 15630949]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGlicklich M, Eliasoph J. Incarcerated obturator hernia: case diagnosed at barium enema fluoroscopy. Radiology. 1989 Jul:172(1):51-2 [PubMed PMID: 2740520]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAnderson T, Bessoff KE, Spain D, Choi J. Contemporary management of obturator hernia. Trauma surgery & acute care open. 2022:7(1):e001011. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2022-001011. Epub 2022 Oct 5 [PubMed PMID: 36213131]

Ghimire SK, Shrestha S, Jha R, Maharjan S, Shrestha M. Small bowel obstruction secondary to strangulated obturator hernia with transected ileal segment: A case report. International journal of surgery case reports. 2025 Apr:129():111098. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2025.111098. Epub 2025 Feb 28 [PubMed PMID: 40054411]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLosanoff JE, Richman BW, Jones JW. Obturator hernia. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2002 May:194(5):657-63 [PubMed PMID: 12022607]

Bergstein JM, Condon RE. Obturator hernia: current diagnosis and treatment. Surgery. 1996 Feb:119(2):133-6 [PubMed PMID: 8571196]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMajor CK, Aziz M, Collins J. Obturator hernia: a case report. Journal of medical case reports. 2021 Jun 17:15(1):319. doi: 10.1186/s13256-021-02793-7. Epub 2021 Jun 17 [PubMed PMID: 34140042]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNaude G, Bongard F. Obturator hernia is an unsuspected diagnosis. American journal of surgery. 1997 Jul:174(1):72-5 [PubMed PMID: 9240957]

Expert Panel on Gastrointestinal Imaging, Garcia EM, Pietryga JA, Kim DH, Fowler KJ, Chang KJ, Kambadakone AR, Korngold EK, Liu PS, Marin D, Moreno CC, Panait L, Santillan CS, Weinstein S, Wright CL, Zreloff J, Carucci LR. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Hernia. Journal of the American College of Radiology : JACR. 2022 Nov:19(11S):S329-S340. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2022.09.016. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36436960]

Ijiri R, Kanamaru H, Yokoyama H, Shirakawa M, Hashimoto H, Yoshino G. Obturator hernia: the usefulness of computed tomography in diagnosis. Surgery. 1996 Feb:119(2):137-40 [PubMed PMID: 8571197]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSiddiqui Z, Khalil M, Khalil A, Saeed S. Obturator hernia: a delayed diagnosis. A case report with literature review. Journal of surgical case reports. 2021 Jan:2021(1):rjaa599. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjaa599. Epub 2021 Jan 25 [PubMed PMID: 33532053]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNg DC, Tung KL, Tang CN, Li MK. Fifteen-year experience in managing obturator hernia: from open to laparoscopic approach. Hernia : the journal of hernias and abdominal wall surgery. 2014 Jun:18(3):381-6. doi: 10.1007/s10029-013-1080-0. Epub 2013 Apr 2 [PubMed PMID: 23546862]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLiu J, Zhu Y, Shen Y, Liu S, Wang M, Zhao X, Nie Y, Chen J. The feasibility of laparoscopic management of incarcerated obturator hernia. Surgical endoscopy. 2017 Feb:31(2):656-660. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5016-5. Epub 2016 Jun 10 [PubMed PMID: 27287915]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePetrie A, Tubbs RS, Matusz P, Shaffer K, Loukas M. Obturator hernia: anatomy, embryology, diagnosis, and treatment. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2011 Jul:24(5):562-9. doi: 10.1002/ca.21097. Epub 2011 Feb 14 [PubMed PMID: 21322061]

Haith LR Jr, Simeone MR, Reilly KJ, Patton ML, Moss BE, Shotwell BA. Obturator hernia: laparoscopic diagnosis and repair. JSLS : Journal of the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons. 1998 Apr-Jun:2(2):191-3 [PubMed PMID: 9876738]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAmiki M, Goto M, Tomizawa Y, Sugiyama A, Sakon R, Inoue T, Ito S, Oneyama M, Shimojima R, Hara Y, Narita K, Tachimori Y, Sekikawa K. Laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal hernioplasty for recurrent obturator hernia: A case report. Asian journal of endoscopic surgery. 2020 Jul:13(3):457-460. doi: 10.1111/ases.12739. Epub 2019 Jul 22 [PubMed PMID: 31332930]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNakayama T, Kobayashi S, Shiraishi K, Nishiumi T, Mori S, Isobe K, Furuta Y. Diagnosis and treatment of obturator hernia. The Keio journal of medicine. 2002 Sep:51(3):129-32 [PubMed PMID: 12371643]

Gokon Y, Ohki Y, Ogino T, Hatoyama K, Oikawa T, Shimizu K, Katsura K, Abe T, Sato K. Manual reduction for incarcerated obturator hernia. Scientific reports. 2023 Apr 4:13(1):5504. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-31634-4. Epub 2023 Apr 4 [PubMed PMID: 37015958]

Arbman G. Strangulated obturator hernia. A simple method for closure. Acta chirurgica Scandinavica. 1984:150(4):337-9 [PubMed PMID: 6377785]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYokoyama Y, Yamaguchi A, Isogai M, Hori A, Kaneoka Y. Thirty-six cases of obturator hernia: does computed tomography contribute to postoperative outcome? World journal of surgery. 1999 Feb:23(2):214-6; discussion 217 [PubMed PMID: 9880435]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLo CY, Lorentz TG, Lau PW. Obturator hernia presenting as small bowel obstruction. American journal of surgery. 1994 Apr:167(4):396-8 [PubMed PMID: 8179083]

Yip AW, AhChong AK, Lam KH. Obturator hernia: a continuing diagnostic challenge. Surgery. 1993 Mar:113(3):266-9 [PubMed PMID: 8441961]

Nakamura A, Harada Y, Oyama H, Tadamura K, Moro H, Kigawa G, Umemoto T, Matsuo K, Tanaka K. Indications for treatment of incidental obturator hernia encountered during transabdominal preperitoneal repair (TAPP). Hernia : the journal of hernias and abdominal wall surgery. 2024 Dec 2:29(1):37. doi: 10.1007/s10029-024-03224-4. Epub 2024 Dec 2 [PubMed PMID: 39623060]