Introduction

Pancreatic serous cystadenomas are mostly benign and considered among the common primary pancreatic cystic neoplasms (PCNs), representing one-third (see Image. Serous Cystadenoma, CT).[1] Patients are usually asymptomatic. Other types of PCNs include mucinous cystic neoplasm, intraductal papillary Mucinous neoplasm, cystic neuroendocrine neoplasm, solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm, acinar-cell cystic neoplasm, and ductal adenocarcinoma with cystic degeneration.[2] Due to the increased use and advances in cross-sectional imaging of the abdomen, the detection of these lesions has improved, especially in asymptomatic patients. This topic discusses the pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of pancreatic serous cystadenoma.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The exact etiology of serous cystadenomas is not well understood. Genetic mutations may contribute to serous cystadenoma formation.[3]

Epidemiology

Pancreatic serous cystadenomas represent one-third of PCNs. Pancreatic serous cystadenomas are almost always benign and occur more commonly in women.[4][5][2] Patients usually present between the 5th and 7th decade of life (mean age 62 years), and the lesions occur more frequently in the body or the tail of the pancreas.[6] Around 77% of patients with von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) syndrome develop pancreatic cystic lesions, 9% of which are serous cystadenomas.[7]

Pathophysiology

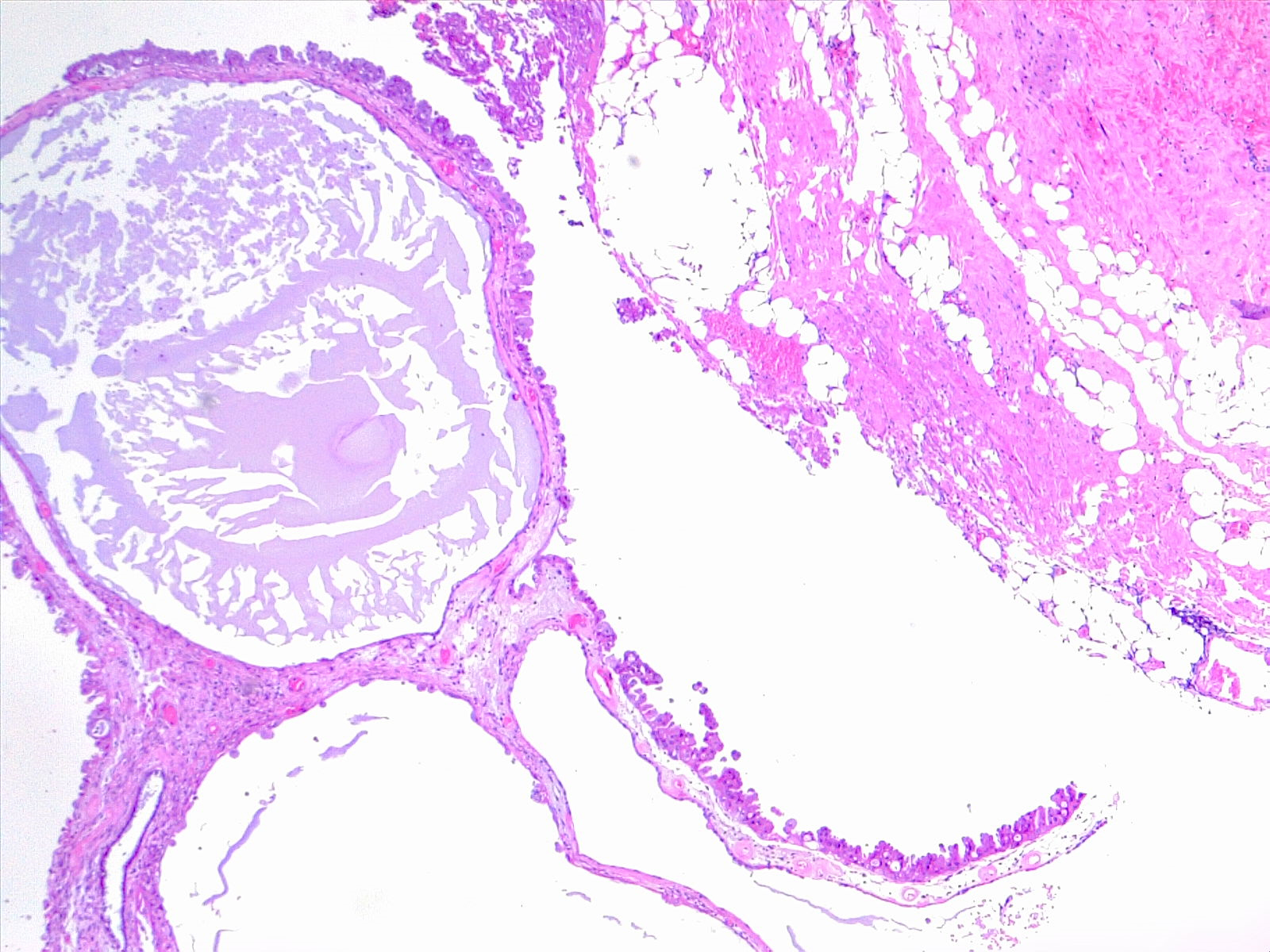

The pathophysiology of pancreatic serous cystadenomas is poorly understood (see Image. Cystadenoma, 4x H/E). The morphologic and immunohistochemical features of the serous neoplasms favor the centroacinar, intralobular, and ductular cells of the pancreas. The WHO classified them into serous microcystic adenomas and serous macrocystic (oligocystic) adenomas.[7] There are macroscopic variants of serous cystadenoma: microcystic serous cystadenoma (most commonly encountered), macrocytic serous cystadenoma (also referred to as oligocystic), solid serous adenoma, VHL-associated serous cystadenomas, and mixed serous-neuroendocrine neoplasm.[8] Macrocystic serous cystadenomas include both previous serous oligocystic and the ill-demarcated serous adenoma. Solid serous adenomas are well-circumscribed and have a solid gross appearance; they have the cytologic and immunohistologic features of classic serous cystadenomas. Serous cystadenomas that occur in VHL syndrome involve the entire pancreas or in a patchy fashion. The mixed serous neuroendocrine neoplasm is a rare serous cystadenoma associated with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. This is also suggestive of VHL syndrome.[8]

Histopathology

Pancreatic serous neoplasms are unifocal, round, well-demarcated, and are often honeycombed. The cysts are loculated, contain mucin-free serous fluid, and are lined by flattened or cuboidal epithelium. Their size can reach to more than 20 cm. They do not communicate with the pancreatic duct. Usually, a dense fibronodular scar is found in the center of the lesion (also called fibrous stellate scar) that is composed of acellular hyalinized tissue and a few clusters of tiny cysts, which are lined by a single layer of cuboidal epithelial cells.[8]

History and Physical

Many patients present without any specific signs or symptoms.[9][10] Often, pancreatic serous cystadenomas are detected incidentally by abdominal ultrasonography or cross-sectional imaging studies performed for another condition. When patients are symptomatic, the most common presentation includes abdominal pain or a palpable mass in the upper abdomen. Less commonly, patients with advanced cystic lesions present similar to those with pancreatic ductal carcinoma, with abdominal pain, weight loss, early satiety secondary to compression of the stomach wall by the adjacent pancreatic mass (gastric outlet obstruction), obstructive jaundice due to obstruction of the biliary tree (may lead to acute cholangitis) and pancreatic duct obstruction causing pancreatic exocrine insufficiency and recurrent pancreatitis.[9][10] True cystic lesions may be confused with pseudocysts, which leads to similarities in the presentations and the characteristics of imaging studies.[11] Pseudocysts usually occur after an episode of acute pancreatitis or insidiously in cases of chronic pancreatitis, and they are frequently associated with pain. Large pseudocysts can compress the stomach, duodenum, or bile duct, resulting in vomiting, early satiety, or obstructive jaundice.

Evaluation

Evaluation of PCNs involves laboratory and imaging modalities to distinguish these types based on morphological and radiological patterns. In the last 15 years, there has been a 20-fold increase in the detection of PCNs, mainly by cross-sectional imaging such as computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).[12] The advent of imaging modalities led to the detection of 4 morphological serous cystadenoma patterns: microcystic, macrocystic, mixed microcystic, and macrocystic and solid.[13] The microcystic pattern was defined as multiple cysts that measure less than 2 cm and are separated by thin fibrous septa, giving a honeycomb appearance.[14] Macrocystic type is diagnosed when cysts ≥2 cm are seen.[15] Mixed microcystic and macrocystic types combine both microcystic and macrocystic patterns. Solid serous cystic neoplasm vs. serous adenoma is a tumor without any cystic lesions on cross-sectional imaging.

Ultrasound: serous microcystic adenoma usually presents as a well-circumscribed, loculated lesion. The fibrous portion of the lesion is hyperechoic, and the cystic portions appear hypoechoic. In lesions where the cysts are only a couple of millimeters in size (microcysts), the tumor appears solid due to the innumerable interfaces. Areas of calcification also appear hyperechoic with posterior acoustic shadowing.

CT scan: serous microcystic adenomas most commonly have a lobular shape.[16][17][18][19] They appear hypodense on unenhanced CT because the tumor is primarily of water density. Calcifications in up to 30% of serous cystadenomas are pathognomic, and a "sunburst" pattern can be seen less commonly. The central fibrous scar is hyperdense and is generally arranged in a stellate pattern known as a "stellate central scar." After the administration of iodinated contrast material, the fibrous portions are enhanced. Because serous microcystic adenomas are considered the only hypervascular cystic pancreatic tumors, their enhancement pattern is an important distinguishing feature. Lesions with fewer fibrous septations show fluid density regardless of contrast administration. Lesions composed primarily of microscopic cysts can have a solid appearance and show homogeneous enhancement after contrast administration.[19] In these cases, as well as all other cystic pancreatic neoplasms, MR imaging is used to characterize the lesion further. On CT, it is often difficult to differentiate the oligocystic pattern from the mucinous neoplasms. Therefore, serous oligocystic adenomas should be suspected when an unilocular cystic lesion with a lobulated contour without wall enhancement is situated in the pancreatic head. Due to cystic degeneration, macrocystic variants may be confused when imaging with pseudocysts or mucinous cysts.[20]

MRI on T1-weighted fat-suppressed imaging shows that the cystic portions are classically hypointense, but areas of hyperintensity may appear if there has been an intracystic hemorrhage.[21] The fibrous components are hypointense on T1-weighted imaging. On T2-weighted images, the cystic fluid-filled components are hyperintense relative to adjacent pancreatic parenchyma, and the fibrous components are hypointense on T2. In addition, any areas of calcification are hypointense on both T1-weighted and T2-weighted imaging, if visible at all. After gadolinium infusion, enhancement of the fibrous septations is visible in the early and late phases of imaging, and it maintains this enhancement of the central scar in more delayed phases of imaging. MR imaging is more sensitive in detecting fluid than CT imaging, especially in the case of microcysts.[22]

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) can readily identify pancreatic cysts through high-resolution imaging. When EUS is used in addition to other imaging modalities, the accuracy of diagnosis is greatly improved by providing high-quality imaging and detecting small areas of closely assembled microcysts. EUS allows for accurate diagnosis in all cases misdiagnosed by other imaging modalities. EUS-guided fine needle aspiration usually provides a definitive diagnosis, but the sensitivity may decrease when there is no adequate sample for analysis.[9][23][24] On EUS, serous cystadenoma usually has multiple small, anechoic cystic areas with thin septations. Because of the vascular nature of serous cystadenoma, aspirates are thin and sometimes bloody or contain hemosiderin-laden macrophages.[25]

Pancreas Cyst fluid analysis includes chemical analysis (Amylase), tumor markers (carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), carbohydrate antigen(CA19-9), and cytology. Serous cystadenoma shows low viscosity, low amylase level, and low CEA levels (<5 to 20 ng/mL), with variable levels of pancreatic enzymes such as Amylase isoenzymes and CA-125. Cancer antigen (CA 72-4) level is low as well. Cytology reveals cuboidal cells with glycogen-rich cytoplasm. Combining these parameters helps classify these cysts and differentiate serous cystadenoma from malignant or mucinous cysts.[26] Cyst fluid DNA analysis may reveal a mutation in VHL among patients with VHL syndrome.[27]

Treatment / Management

When diagnosing pancreatic serous cystadenoma based on clinical and radiographic evidence, non-surgical management should be recommended in asymptomatic cases. Surveillance imaging can be safely recommended based on these cysts' slow growth rate. This is due to the small risk of malignancy (<3%).[28] Surgical resection should be the next step in the management of symptomatic patients due to rapidly growing lesions (cystadenoma itself vs. hemorrhage), giant tumors more than 10 cm (causing mass effect, obstructive jaundice, pancreatic duct obstruction causing pancreatic exocrine insufficiency or gastric outlet obstruction) or when malignancy (for example serous cystadenocarcinoma) cannot be excluded.[29] Although the increased size does not predict malignancy, large lesions are usually known to grow faster, making them more likely to cause symptoms.[3] The surgical approach depends on the location and may include distal pancreatectomy with or without splenectomy, mid pancreatectomy, or Whipple procedure. Enucleation was previously reported as a safe option for well-selected patients with serous cystadenoma, preserving the endocrine and exocrine pancreas function.[30](B2)

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions could be difficult, especially if it is based solely on radiological studies. It is known that most pancreatic cystic lesions are inflammatory, which are considered pseudocysts, and the minority are considered neoplastic.[23][24][31] It is equally problematic to distinguish benign serous from mucinous (mucinous cystic neoplasm) and malignant mucinous lesions (mucinous cystadenocarcinoma), therefore implementing radiologic, morphologic and laboratory tests help in distinguishing these lesions before resection and assessing their malignant potential. It is also essential to distinguish pseudocysts from serous lesions as it is essential for planning appropriate surgical management.[23][24][31] A rare entity of cystic pancreatic lesions includes cystic islet cell tumors, papillary cystic lesions, and lymphoepithelial cysts. The differential diagnosis for serous cystadenomas can be summarized as follows:

- Non-neoplastic pancreatic cysts: true cysts, retention cysts, mucinous non-neoplastic cysts, lymphoepithelial cysts.

- Pancreatic cystic neoplasms include mucinous, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and solid pseudopapillary neoplasms.

- Cystic degeneration in solid pancreatic tumors includes ductal carcinoma, acinar cell carcinoma, and endocrine tumors.

Prognosis

Serous cystadenomas are considered benign with a small malignant potential (<3%). During long-term follow-up in a clinical study of 18 patients with serous cystadenomas, the following morphologic changes were seen in 3 tumors (17%): microcystic serous cystadenoma changed to macrocystic serous cystadenoma and was associated with tumor enlargement in 1 patient, macrocystic serous cystadenoma changed to micro and macrocystic serous cystadenoma resulting in a mixed type with tumor enlargement in the second patient. In the third patient, the macrocystic serous cystadenoma changed to a microcystic serous cystadenoma with associated tumor shrinkage from 30 to 25 mm. So, of the 18 patients, 9 cases (50%) had an enlargement of the tumor, and in the remaining 9 cases (50%), there was no change in size. The median growth rate was 0.29 cm per year.[29] The prognosis for patients with serous cystadenomas is excellent. Even in rare cases of serous cystadenocarcinoma, there are reports of long-term survival after resection. Studies also conclude that any serous cystadenoma has the potential to grow with time, regardless of the tumor subtype, size, or location. That's why all serous cystic neoplasms should be followed up regularly.

Complications

Physicians must evaluate the risks and benefits of surveillance imaging vs. surgical resection. Operative mortality was probably underestimated. Pancreatic surgical morbidity in the short and long term remains high, with pancreatic fistulae formation and exocrine or endocrine (diabetes mellitus) pancreatic insufficiency in around one-third of cases.[1] If growing serous cystadenomas are left untreated, they can lead to pancreatitis, obstructive jaundice due to obstruction of the biliary tree, which can lead to cholangitis, pancreatic exocrine insufficiency due to pancreatic duct obstruction, or gastric outlet obstruction.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education and reassurance are essential, as most serous cystadenomas are benign. Most of these lesions are discovered incidentally on cross-sectional imaging; however, patients' knowledge of their own personal and family history regarding previous episodes of pancreatitis may lead to the formation of pseudocysts or any hereditary or genetic familial syndrome that may be associated with pancreatic lesions as in VHL syndrome can be very helpful. Patients should be counseled about the importance of reporting new symptoms such as jaundice, abdominal pain, and early satiety that warrant further investigation to assess for complicated disease and rule out pancreatic tumors. In addition, patient education about the importance of regular surveillance imaging is essential, given the great impact on the prognosis and survival rates in case the tumor grows in size or has any degree of dysplasia.

Pearls and Other Issues

Recent developments in the diagnosis and treatment of PCNs have been made. Ex vivo optical coherence tomography (OCT) of freshly resected pancreatectomy specimens has shown that mucinous cysts could be differentiated from nonmucinous cysts. OCT is an interferometric technique that typically uses near-infrared light. It allows noninvasive assessment of biological tissues by measuring their optical reflections.[32] Confocal laser endomicroscopy (CLE) is a novel imaging technology that uses a low-power laser. Needle-based CLE (nCLE) is used for intraabdominal organs under EUS guidance. The nCLE mini probe is introduced into the lesion through an FNA needle to obtain a biopsy. Pancreatitis was reported as an adverse complication in a few cases. EUS-guided pancreatic cyst ablation uses EUS guidance to inject a cytotoxic agent, either ethanol or paclitaxel, after the puncture of the pancreatic cyst. The injection of a cytotoxic agent may ablate the cyst epithelium.[33]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

There are many suggested algorithms for managing pancreatic cystic lesions. Emphasis is placed on the size and morphology of the pancreatic cysts. The main issue in managing serous cystic neoplasm is accurately diagnosing the serous cystadenoma. Surgical intervention is only indicated if all investigations have been completed and there is still a doubt about a pancreatic neoplasm.[34] Physicians should first suggest conservative management surveillance imaging according to the available guidelines unless the initial diagnosis concerns a complicated disease or malignancy and warrants immediate intervention.

Media

References

Jais B, Rebours V, Malleo G, Salvia R, Fontana M, Maggino L, Bassi C, Manfredi R, Moran R, Lennon AM, Zaheer A, Wolfgang C, Hruban R, Marchegiani G, Fernández Del Castillo C, Brugge W, Ha Y, Kim MH, Oh D, Hirai I, Kimura W, Jang JY, Kim SW, Jung W, Kang H, Song SY, Kang CM, Lee WJ, Crippa S, Falconi M, Gomatos I, Neoptolemos J, Milanetto AC, Sperti C, Ricci C, Casadei R, Bissolati M, Balzano G, Frigerio I, Girelli R, Delhaye M, Bernier B, Wang H, Jang KT, Song DH, Huggett MT, Oppong KW, Pererva L, Kopchak KV, Del Chiaro M, Segersvard R, Lee LS, Conwell D, Osvaldt A, Campos V, Aguero Garcete G, Napoleon B, Matsumoto I, Shinzeki M, Bolado F, Fernandez JM, Keane MG, Pereira SP, Acuna IA, Vaquero EC, Angiolini MR, Zerbi A, Tang J, Leong RW, Faccinetto A, Morana G, Petrone MC, Arcidiacono PG, Moon JH, Choi HJ, Gill RS, Pavey D, Ouaïssi M, Sastre B, Spandre M, De Angelis CG, Rios-Vives MA, Concepcion-Martin M, Ikeura T, Okazaki K, Frulloni L, Messina O, Lévy P. Serous cystic neoplasm of the pancreas: a multinational study of 2622 patients under the auspices of the International Association of Pancreatology and European Pancreatic Club (European Study Group on Cystic Tumors of the Pancreas). Gut. 2016 Feb:65(2):305-12. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309638. Epub 2015 Jun 4 [PubMed PMID: 26045140]

Brugge WR, Lauwers GY, Sahani D, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Warshaw AL. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. The New England journal of medicine. 2004 Sep 16:351(12):1218-26 [PubMed PMID: 15371579]

Tseng JF, Warshaw AL, Sahani DV, Lauwers GY, Rattner DW, Fernandez-del Castillo C. Serous cystadenoma of the pancreas: tumor growth rates and recommendations for treatment. Annals of surgery. 2005 Sep:242(3):413-9; discussion 419-21 [PubMed PMID: 16135927]

Del Chiaro M, Verbeke C, Salvia R, Klöppel G, Werner J, McKay C, Friess H, Manfredi R, Van Cutsem E, Löhr M, Segersvärd R, European Study Group on Cystic Tumours of the Pancreas. European experts consensus statement on cystic tumours of the pancreas. Digestive and liver disease : official journal of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology and the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver. 2013 Sep:45(9):703-11. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2013.01.010. Epub 2013 Feb 14 [PubMed PMID: 23415799]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYoon WJ, Lee JK, Lee KH, Ryu JK, Kim YT, Yoon YB. Cystic neoplasms of the exocrine pancreas: an update of a nationwide survey in Korea. Pancreas. 2008 Oct:37(3):254-8. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181676ba4. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18815545]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGalanis C, Zamani A, Cameron JL, Campbell KA, Lillemoe KD, Caparrelli D, Chang D, Hruban RH, Yeo CJ. Resected serous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: a review of 158 patients with recommendations for treatment. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery : official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. 2007 Jul:11(7):820-6 [PubMed PMID: 17440789]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHammel PR, Vilgrain V, Terris B, Penfornis A, Sauvanet A, Correas JM, Chauveau D, Balian A, Beigelman C, O'Toole D, Bernades P, Ruszniewski P, Richard S. Pancreatic involvement in von Hippel-Lindau disease. The Groupe Francophone d'Etude de la Maladie de von Hippel-Lindau. Gastroenterology. 2000 Oct:119(4):1087-95 [PubMed PMID: 11040195]

Klöppel G, Solcia E, Capella C, Heitz PU. Classification of neuroendocrine tumours. Italian journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 1999 Oct:31 Suppl 2():S111-6 [PubMed PMID: 10604114]

Bassi C, Salvia R, Molinari E, Biasutti C, Falconi M, Pederzoli P. Management of 100 consecutive cases of pancreatic serous cystadenoma: wait for symptoms and see at imaging or vice versa? World journal of surgery. 2003 Mar:27(3):319-23 [PubMed PMID: 12607059]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKerlin DL, Frey CF, Bodai BI, Twomey PL, Ruebner B. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Surgery, gynecology & obstetrics. 1987 Dec:165(6):475-8 [PubMed PMID: 2446398]

Warshaw AL, Rutledge PL. Cystic tumors mistaken for pancreatic pseudocysts. Annals of surgery. 1987 Apr:205(4):393-8 [PubMed PMID: 3566376]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKhalid A, Brugge W. ACG practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of neoplastic pancreatic cysts. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2007 Oct:102(10):2339-49 [PubMed PMID: 17764489]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKimura W, Moriya T, Hirai I, Hanada K, Abe H, Yanagisawa A, Fukushima N, Ohike N, Shimizu M, Hatori T, Fujita N, Maguchi H, Shimizu Y, Yamao K, Sasaki T, Naito Y, Tanno S, Tobita K, Tanaka M. Multicenter study of serous cystic neoplasm of the Japan pancreas society. Pancreas. 2012 Apr:41(3):380-7. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31822a27db. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22415666]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJohnson CD, Stephens DH, Charboneau JW, Carpenter HA, Welch TJ. Cystic pancreatic tumors: CT and sonographic assessment. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 1988 Dec:151(6):1133-8 [PubMed PMID: 3055888]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChoi JY, Kim MJ, Lee JY, Lim JS, Chung JJ, Kim KW, Yoo HS. Typical and atypical manifestations of serous cystadenoma of the pancreas: imaging findings with pathologic correlation. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2009 Jul:193(1):136-42. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1309. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19542405]

Kim SY, Lee JM, Kim SH, Shin KS, Kim YJ, An SK, Han CJ, Han JK, Choi BI. Macrocystic neoplasms of the pancreas: CT differentiation of serous oligocystic adenoma from mucinous cystadenoma and intraductal papillary mucinous tumor. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2006 Nov:187(5):1192-8 [PubMed PMID: 17056905]

Khurana B, Mortelé KJ, Glickman J, Silverman SG, Ros PR. Macrocystic serous adenoma of the pancreas: radiologic-pathologic correlation. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2003 Jul:181(1):119-23 [PubMed PMID: 12818841]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCohen-Scali F, Vilgrain V, Brancatelli G, Hammel P, Vullierme MP, Sauvanet A, Menu Y. Discrimination of unilocular macrocystic serous cystadenoma from pancreatic pseudocyst and mucinous cystadenoma with CT: initial observations. Radiology. 2003 Sep:228(3):727-33 [PubMed PMID: 12954892]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceProcacci C, Graziani R, Bicego E, Bergamo-Andreis IA, Guarise A, Valdo M, Bogina G, Solarino U, Pistolesi GF. Serous cystadenoma of the pancreas: report of 30 cases with emphasis on the imaging findings. Journal of computer assisted tomography. 1997 May-Jun:21(3):373-82 [PubMed PMID: 9135643]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePanarelli NC, Park KJ, Hruban RH, Klimstra DS. Microcystic serous cystadenoma of the pancreas with subtotal cystic degeneration: another neoplastic mimic of pancreatic pseudocyst. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2012 May:36(5):726-31. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31824cf879. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22498822]

Sahni VA, Mortelé KJ. The bloody pancreas: MDCT and MRI features of hypervascular and hemorrhagic pancreatic conditions. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2009 Apr:192(4):923-35. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1602. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19304696]

Mottola JC, Sahni VA, Erturk SM, Swanson R, Banks PA, Mortele KJ. Diffusion-weighted MRI of focal cystic pancreatic lesions at 3.0-Tesla: preliminary results. Abdominal imaging. 2012 Feb:37(1):110-7. doi: 10.1007/s00261-011-9737-6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21512724]

Compagno J, Oertel JE. Mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas with overt and latent malignancy (cystadenocarcinoma and cystadenoma). A clinicopathologic study of 41 cases. American journal of clinical pathology. 1978 Jun:69(6):573-80 [PubMed PMID: 665578]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWarshaw AL, Compton CC, Lewandrowski K, Cardenosa G, Mueller PR. Cystic tumors of the pancreas. New clinical, radiologic, and pathologic observations in 67 patients. Annals of surgery. 1990 Oct:212(4):432-43; discussion 444-5 [PubMed PMID: 2171441]

Lennon AM, Rintoul RC, Penman ID. Competition for EUS (a) EBUS-TBNA (b) video assisted thoracoscopy. Endoscopy. 2006 Jun:38 Suppl 1():S80-3 [PubMed PMID: 16802233]

Lewandrowski KB, Southern JF, Pins MR, Compton CC, Warshaw AL. Cyst fluid analysis in the differential diagnosis of pancreatic cysts. A comparison of pseudocysts, serous cystadenomas, mucinous cystic neoplasms, and mucinous cystadenocarcinoma. Annals of surgery. 1993 Jan:217(1):41-7 [PubMed PMID: 8424699]

Springer S, Wang Y, Dal Molin M, Masica DL, Jiao Y, Kinde I, Blackford A, Raman SP, Wolfgang CL, Tomita T, Niknafs N, Douville C, Ptak J, Dobbyn L, Allen PJ, Klimstra DS, Schattner MA, Schmidt CM, Yip-Schneider M, Cummings OW, Brand RE, Zeh HJ, Singhi AD, Scarpa A, Salvia R, Malleo G, Zamboni G, Falconi M, Jang JY, Kim SW, Kwon W, Hong SM, Song KB, Kim SC, Swan N, Murphy J, Geoghegan J, Brugge W, Fernandez-Del Castillo C, Mino-Kenudson M, Schulick R, Edil BH, Adsay V, Paulino J, van Hooft J, Yachida S, Nara S, Hiraoka N, Yamao K, Hijioka S, van der Merwe S, Goggins M, Canto MI, Ahuja N, Hirose K, Makary M, Weiss MJ, Cameron J, Pittman M, Eshleman JR, Diaz LA Jr, Papadopoulos N, Kinzler KW, Karchin R, Hruban RH, Vogelstein B, Lennon AM. A combination of molecular markers and clinical features improve the classification of pancreatic cysts. Gastroenterology. 2015 Nov:149(6):1501-10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.041. Epub 2015 Aug 4 [PubMed PMID: 26253305]

Strobel O, Z'graggen K, Schmitz-Winnenthal FH, Friess H, Kappeler A, Zimmermann A, Uhl W, Büchler MW. Risk of malignancy in serous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Digestion. 2003:68(1):24-33 [PubMed PMID: 12949436]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFukasawa M, Maguchi H, Takahashi K, Katanuma A, Osanai M, Kurita A, Ichiya T, Tsuchiya T, Kin T. Clinical features and natural history of serous cystic neoplasm of the pancreas. Pancreatology : official journal of the International Association of Pancreatology (IAP) ... [et al.]. 2010:10(6):695-701. doi: 10.1159/000320694. Epub 2011 Jan 18 [PubMed PMID: 21242709]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGe C, Luo X, Chen X, Guo K. Enucleation of pancreatic cystadenomas. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery : official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. 2010 Jan:14(1):141-7. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1023-3. Epub 2009 Sep 25 [PubMed PMID: 19779948]

Compagno J, Oertel JE. Microcystic adenomas of the pancreas (glycogen-rich cystadenomas): a clinicopathologic study of 34 cases. American journal of clinical pathology. 1978 Mar:69(3):289-98 [PubMed PMID: 637043]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHee MR, Izatt JA, Swanson EA, Huang D, Schuman JS, Lin CP, Puliafito CA, Fujimoto JG. Optical coherence tomography of the human retina. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1995 Mar:113(3):325-32 [PubMed PMID: 7887846]

Brugge WR. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Ablation of Pancreatic Cysts. Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2018 Oct:14(10):602-604 [PubMed PMID: 30774574]

Yoon WJ, Brugge WR. Pancreatic cystic neoplasms: diagnosis and management. Gastroenterology clinics of North America. 2012 Mar:41(1):103-18. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2011.12.016. Epub 2012 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 22341252]