Introduction

Paracentesis is a fundamental procedure in evaluating and managing ascites, defined as the abnormal fluid accumulation within the peritoneal cavity.[1] The procedure involves inserting a needle into the peritoneal space to remove ascitic fluid, which may be performed for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes.[2] Diagnostic paracentesis is essential for determining ascites' etiology and ruling out infection, particularly spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP). Therapeutic paracentesis allows for removing large volumes of fluid to alleviate the significant discomfort and respiratory compromise associated with tense ascites. Ascitic fluid analysis should be performed in all patients with new-onset ascites; timely intervention is critical. In fact, study results demonstrate that patients with suspected SBP who undergo delayed paracentesis face a 2.7-fold increased risk of mortality compared to those receiving early paracentesis within 12 hours of initial physician evaluation.[3]

Cirrhosis of the liver is the most common underlying cause of ascites, and its presence significantly worsens prognosis.[4] Patients with cirrhosis and ascites have an estimated 1-year mortality of 20%, compared to 7% in patients with cirrhosis but without ascites.[5] Given these risks, paracentesis is a cornerstone of initial evaluation and a life-saving intervention in appropriate contexts. This review will address the indications, contraindications, and potential complications of paracentesis, while also emphasizing the role of an interprofessional care team in optimizing outcomes. Physicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, and other healthcare professionals are critical in ensuring early recognition, prompt diagnostic evaluation, and safe therapeutic fluid removal. In treating liver disease as a global health burden, proficiency in paracentesis and evidence-based care coordination are indispensable skills for healthcare professionals.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Paracentesis is a procedure performed in patients with ascites, in which a needle is inserted into the peritoneal cavity to obtain or remove ascitic fluid. Ascites, defined as the abnormal fluid accumulation within the peritoneal cavity, typically arise from portal hypertension, decreased oncotic pressure, or impaired lymphatic drainage. In cirrhosis, increased hydrostatic pressure within the splanchnic circulation and hypoalbuminemia result in progressive fluid accumulation. Removing this fluid through paracentesis alleviates intra-abdominal pressure, restores diaphragmatic excursion, and improves symptoms such as abdominal discomfort, dyspnea, and early satiety. However, large-volume fluid removal can precipitate paracentesis-induced circulatory dysfunction, underscoring the importance of intravenous (IV) albumin infusion when more than 5 liters are drained.

The procedure is usually performed with the patient in the supine position. However, a wedge may be placed beneath one side of the body to mobilize fluid toward a dependent quadrant and enhance access. Paracentesis may be performed with or without imaging guidance; however, substantial data demonstrate that ultrasound-guided techniques offer superior safety and efficacy.[6] When performed without imaging, the left lower quadrant is considered the safest site, given its thinner abdominal wall and greater likelihood of containing a deeper fluid pocket, as demonstrated in the study by Sakai et al.[7]

Several key anatomical considerations must be respected to minimize complications. Entry should be planned away from surgical scars and visible abdominal wall veins. At the same time, vital structures such as the spleen, inferior epigastric arteries, and the cecum should be avoided when accessing the right lower quadrant. The preferred entry site is in the lower quadrant, lateral to the rectus abdominis muscle and 2 to 4 cm superomedial to the anterior superior iliac spine. This landmark minimizes the risk of injury to the inferior epigastric artery.[2][8] The needle should be introduced at a 45-degree angle or via the z-tracking technique to reduce the chance of postprocedural ascitic leakage. A comprehensive understanding of the abdominal wall anatomy, fluid distribution within the peritoneal cavity, and the physiological consequences of fluid removal is essential for performing safe and effective paracentesis.

Indications

Paracentesis is performed for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes, with indications depending on the clinical context. Diagnostic paracentesis is recommended in several situations. Patients with known ascites should undergo paracentesis to rule out SBP when presenting with concerning features such as abdominal pain, fever, gastrointestinal bleeding, worsening encephalopathy, new or progressive renal or hepatic dysfunction, hypotension, or other signs of infection or sepsis. Evaluating ascitic fluid is also essential in cases of new-onset ascites, as fluid analysis helps determine the underlying etiology, differentiate between transudative and exudative causes, identify malignant cells, and rule out other conditions. Additionally, any hospitalized individual with ascites should undergo diagnostic paracentesis, as recommended by current guidelines, to exclude occult infection.

Therapeutic paracentesis is indicated in hemodynamically stable individuals with tense ascites, particularly when ascites is refractory to diuretics or causing significant abdominal discomfort and respiratory compromise.[2][8] Large-volume paracentesis (LVP), defined as removing more than 5 liters of fluid, is frequently required in these patients.[2] IV albumin infusion is generally recommended when more than 5 liters are removed to mitigate complications such as paracentesis-induced circulatory dysfunction. Bureau et al described a novel low-flow pump system that transfers ascitic fluid into the urinary bladder for excretion during micturition, demonstrating improved quality of life and reducing the need for repeated LVP in patients with refractory ascites.[9]

Paracentesis may also play a role in patients with abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) secondary to tense ascites. Although surgical decompression via laparotomy remains the definitive treatment in ACS, LVP can provide a temporizing reduction in intra-abdominal pressure and decrease the risk of hemodynamic collapse.[10] Additional physiologic benefits of paracentesis have been documented. Wittmer et al evaluated 30 patients with cirrhosis and ascites, reporting significant improvement in abdominal breathing mechanics, thoracoabdominal mobility, ventilatory parameters, and oxygen saturation following paracentesis.[11] Patients also experienced reduced dyspnea and fatigue, further supporting the role of therapeutic paracentesis in improving overall quality of life.

Historically, paracentesis under ultrasonographic guidance has been used for hospital palliative care. However, some patients may have difficulty reaching the hospital. Home-based palliative paracentesis is a safe, effective, and convenient option for such patients. This was reported by Ota et al in a case series of patients with ascites.[12] Home-based abdominal paracentesis in refractory congestive heart failure cases is a better alternative to periodic percutaneous paracentesis. A study by Kunin et al demonstrated that it improved symptoms in patients on peritoneal dialysis without needing peritoneal exchanges for fluid.[13]

Contraindications

There are a few absolute contraindications for paracentesis.[14] These include:

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation

- An acute abdomen requiring surgery

The relative contraindications of paracentesis include the following:

- Pregnancy

- Organomegaly

- Ileus

- Intestinal obstruction

- Distended bladder

- Surgical scars

- The bowel may adhere to the abdominal wall near surgical scars; hence, the needle insertion location should be away from the scar to decrease the risk of bowel perforation.

- Clotting derangements (ie, severe thrombocytopenia where platelets are less than 20 × 103/μL and an international normalized ratio [INR] more than 2.0)

- Abnormal coagulation studies and thrombocytopenia (common in cirrhotic patients) are not absolute contraindications, as the incidence of bleeding complications from the procedure is very low.[15] PA McVay and PT Toy demonstrated that only 0.2% of patients undergoing paracentesis required transfusion due to the incidence of bleeding, and the patients who required transfusion had platelets less than 20,000/µL.[15] Clinicians can consider platelet transfusion before paracentesis if platelets are less than 20,000/µL. The same study also demonstrated that patients with renal failure had a higher risk of bleeding complications; hence, it may be reasonable to consider desmopressin administration before paracentesis in patients with cirrhosis and renal failure.

- The liver produces pro- and anticoagulant proteins, and in cirrhotic patients, the balance of these proteins is not well measured by conventional tests such as prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time, or INR.[16] Many clinicians even to this day respond inappropriately to abnormal coagulation studies and transfuse fresh frozen plasma (FFP) before paracentesis as they believe that patients with cirrhosis and abnormal PT and INR are "autoanticoagulated," however a study performed on 190 patients with chronic liver disease demonstrated that an elevated INR in this patient population may not protect against venous thromboembolism providing more evidence that patients with abormal coagulation studies in the seting of chronic liver disease may not be "autoanticoagulated."[16] Administering FFP to patients before paracentesis is not indicated, as studies have demonstrated that LVP can be performed without a significant increase in bleeding-related complications and postprocedure transfusion despite an INR as high as 8.7.[17]

- In patients with no prior history and without clinical evidence of active bleeding, tests such as PT, activated partial thromboplastin time, and platelet count may not be required before the procedure.[15]

Ultrasound-guided paracentesis should be performed in patients with relative contraindications to paracentesis. The success and safety of a blind paracentesis depend on the volume of ascitic fluid.[18] By performing a paracentesis using ultrasound guidance, the healthcare professionals can identify the ascitic fluid and evaluate the procedure's safety by confirming the absence of solid organs, bowel, bladder, and blood vessels in the expected needle track.[14] Results from a study performed on 1300 patients undergoing diagnostic and therapeutic paracentesis demonstrated that ultrasound-guided paracentesis was associated with lower costs and complication rates (1.4% vs 4.7%, odds ratio of 0.349) compared to paracentesis performed without ultrasound guidance.[19]

Equipment

Prepackaged paracentesis kits come with all the equipment required for paracentesis. Alternatively, traditional large-bore IV catheters or 18-gauge to 20-gauge standard or spinal needles can be used; these can be attached to a syringe for aspiration and IV tubing for fluid drainage in resource-poor settings. If these prepackaged kits are not available, the following items will be needed:

- Ultrasound machine

- Sterile gloves

- Antiseptic swab sticks

- Alcohol wipes

- Sterile gauze, 4 x 4 inches

- Scalpel, #11 blade

- Sterile drapes/towels

- Lidocaine 1%, 5 mL ampule

- Skin anesthesia needles (25- or 27-gauge)

- Two 22-gauge injection needles

- 18-gauge needle for inoculation of blood culture bottles

- Catheter, 8 French, over 15- or 18-gauge × 7.5-inch (19 cm) needle with 3-way stopcock and self-sealing valve

- Sterile syringes (5, 20, or 60 mL) to collect fluid

- Tubing set with roller clamp

- Drainage bag or vacuum container

- Red-top tube, purple-top tube, 2 blood culture bottles [14]

Personnel

To independently perform a paracentesis, clinicians should complete a minimum of 10 supervised procedures under the guidance of an experienced physician to establish competency.[17] Ongoing assessment of procedural proficiency is essential, with regular monitoring of complication rates to ensure patient safety and maintain quality standards.[20] The procedure should ideally be performed with an assistant available to help the operator once sterile gown and gloves are donned, ensuring smooth workflow and adherence to sterile technique. In addition to physicians, advanced clinical providers, nurses, and trainees may play essential roles in the performance and support of paracentesis, provided that appropriate supervision, training, and competency assessments are in place.

Preparation

Consent

Before performing paracentesis, the clinician should explain the procedure's purpose, potential risks, expected benefits, possible complications, and alternative options. Informed consent must be obtained and documented from the patient or a legally authorized representative.

Portal of Entry

The preferred site of needle entry is the right or left lower quadrant of the abdomen, lateral to the rectus sheath and superior to the anterior superior iliac spine. This approach minimizes the risk of puncturing abdominal collateral vessels and the inferior epigastric artery. Commonly recommended entry sites include:

- Midline approach: 2 cm below the umbilicus through the linea alba

- Lateral approach: 5 cm superior and medial to the anterior superior iliac spine on either side

Positioning

Paracentesis is typically performed with the patient in the supine position. To improve access to ascitic fluid in a particular quadrant, a wedge may be placed under 1 side of the body, allowing the patient to lean slightly to the right or left. Patients should also empty their bladder before the procedure to reduce the risk of bladder injury.

Imaging

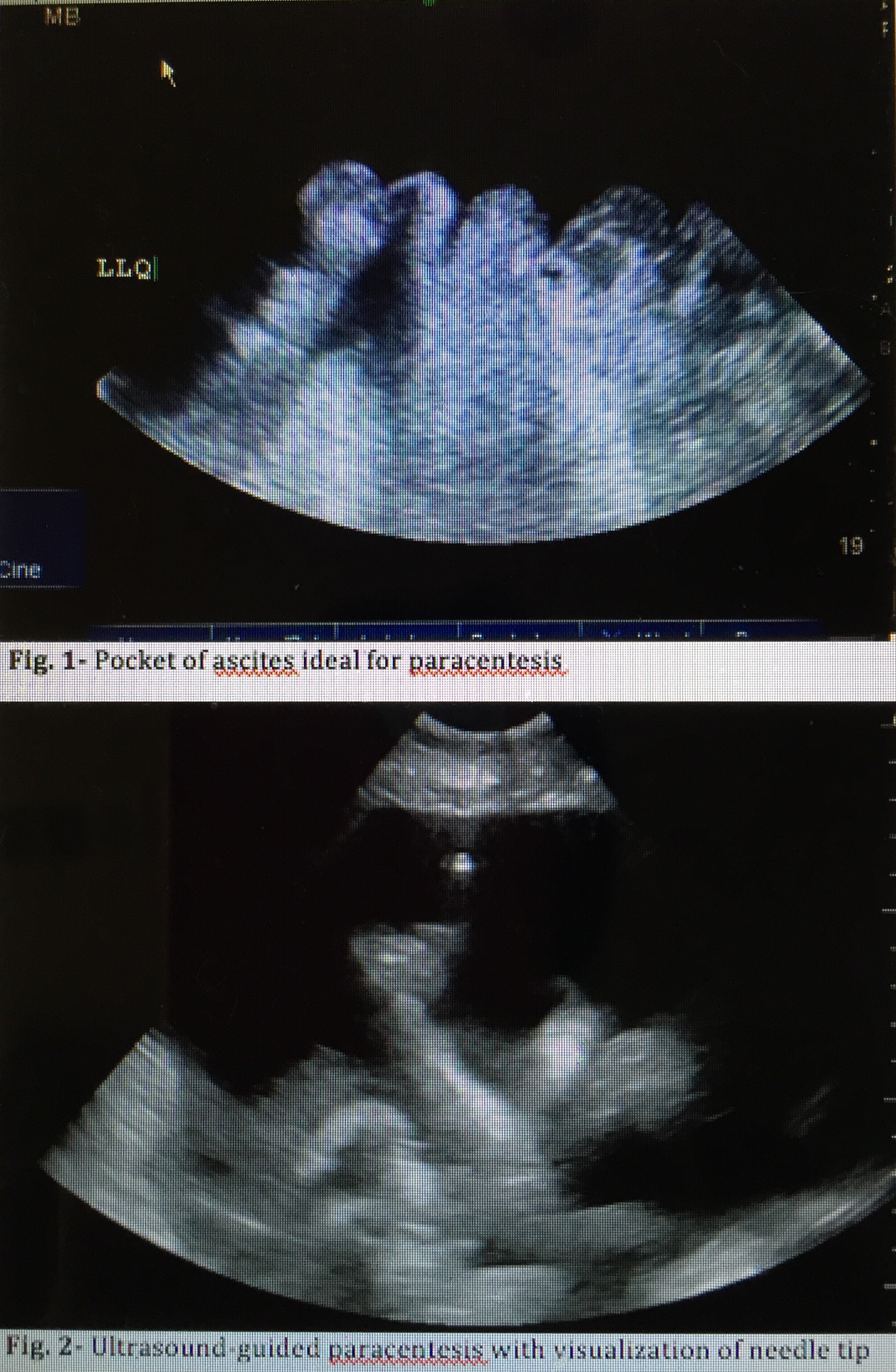

Bedside ultrasound guidance is recommended to identify an appropriate location for the procedure.[21] Ultrasound can confirm the presence of fluid and identify an area with sufficient fluid for aspiration, decreasing the incidence of unsuccessful aspiration and complications (see Image. Ultrasound-Guided Paracentesis). Ultrasound increases the success rate of paracentesis and helps prevent an unnecessary invasive procedure in some patients.[22] The procedure can be performed either after marking the insertion site or in real-time by advancing the needle under direct ultrasound guidance. Performing an ultrasound also helps the clinician avoid small bowel adhesions or a distended urinary bladder below the entry point. Avoiding areas of prominent veins (caput medusae), scar tissue, and infected skin is critical to minimize complications.

Technique or Treatment

Skin Preparation and Sterilization

The procedure begins with skin antisepsis using either povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine. A sterile drape with an opening over the procedure site should be applied, and the skin may be sterilized again within the exposed field. The antiseptic solution must be allowed to dry fully to ensure sterility.

Local Anesthesia

The operator dons sterile gloves and prepares 5 mL of 1% lidocaine. If using a multidose vial, the assistant should disinfect the vial top with an alcohol swab before drawing the anesthetic. The skin is first entered tangentially to raise a small wheal of anesthesia. The needle is then reinserted perpendicularly through the anesthetized track, with intermittent aspiration during advancement to check for inadvertent vascular puncture. If no blood return is seen, lidocaine is infiltrated into the subcutaneous tissues and abdominal wall. Advancement continues until peritoneal entry is confirmed by aspiration of yellow ascitic fluid.

Needle and Catheter Insertion

The paracentesis needle, IV catheter, or prepackaged catheter kit is introduced along the anesthetized path using the Z-track method, which reduces postprocedural fluid leakage. This technique involves displacing the skin caudally before needle advancement; once the peritoneal cavity is entered, the skin is released, creating a misaligned tract. When using a catheter kit with a large-bore (15-gauge) introducer needle, a small skin nick with an 11-blade scalpel can facilitate catheter passage.

During insertion, negative pressure should be intermittently applied to the syringe until a loss of resistance and free flow of ascitic fluid are achieved. This maneuver helps confirm peritoneal entry while avoiding inadvertent puncture of a vessel or viscus. Once ascitic fluid is aspirated, the catheter is advanced into the peritoneal cavity, and the needle is withdrawn.

Fluid Collection and Sampling

An initial 25 to 30 mL of fluid should be collected for analysis. Recommended sample distribution includes:

- Purple-top tube: cell count and differential

- Red-top tube: biochemical analysis

- Blood culture bottles: ~10 mL each, which has been shown to improve culture sensitivity [2]

Following diagnostic sampling, the catheter can be connected via stopcock and tubing to a vacuum bottle, plastic drainage canister, or collection bag for therapeutic removal of larger fluid volumes. After drainage, the catheter is removed, and manual pressure is applied to achieve hemostasis at the insertion site.[8][14]

Equipment and Safety Considerations

Kelil et al demonstrated that wall suction and plastic canisters represent safe, cost-effective alternatives to evacuated glass bottles for fluid drainage.[23] For patients undergoing LVP (>5 L removed), colloid (eg, albumin) replacement should be considered to reduce the risk of post-paracentesis circulatory dysfunction.

Peritoneal Fluid Analysis

The 2 most common indications for paracentesis are:

- To rule out spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP)

- To evaluate the etiology of ascites

Accordingly, fluid testing should be directed at answering these clinical questions.

Initial Tests

- Appearance

- Clear fluid suggests uncomplicated ascites.

- Milky fluid indicates elevated triglyceride concentration; fluid triglyceride levels should be measured to assess for chylous ascites.

- Red or hemorrhagic fluid raises suspicion for malignant ascites or tuberculous peritonitis. Additional tests may include fluid lactate dehydrogenase, adenosine deaminase, cytology, and tumor markers (eg, carcinoembryonic antigen).

- Cell count and differential

- SBP is diagnosed when the absolute neutrophil count is ≥250 cells/mm³.[2]

- This is calculated by multiplying the total white cell count by the percentage of neutrophils in the differential.

- Protein concentration

- Total protein in ascitic fluid helps differentiate between cardiac and cirrhotic causes of portal hypertension-related ascites (see below).

- Albumin concentration

- Gram stain

- Fluid culture

- Cultures should be sent in blood culture bottles to improve sensitivity.

- Empiric antibiotics (usually a third-generation cephalosporin or fluoroquinolone) should be initiated immediately in patients with ascites and high suspicion of SBP, even before cell count results are available, or in any patient with an absolute neutrophil count ≥250 cells/mm³.

- In patients with SBP, 25% albumin infusion (1.5 g/kg on day 1) should be administered unless contraindicated (eg, hypoxia, pulmonary edema, end-stage renal disease, decompensated heart failure). Albumin therapy reduces the risk of acute kidney injury and hepatorenal syndrome.[26]

Ascites Etiology Based on SAAG

- SAAG ≥1.1 g/dL (portal hypertension–related ascites)

- Hepatic cirrhosis

- Heart failure

- Alcoholic hepatitis

- Fulminant hepatic failure

- Nephrotic syndrome

- Portal vein thrombosis

- Ascitic total protein >2.5 g/dL → more likely heart failure

- Ascitic total protein <2.5 g/dL → more likely cirrhosis

- SAAG <1.1 g/dL (nonportal hypertension ascites)

- Peritoneal carcinomatosis

- Pancreatitis

- Peritonitis (tuberculous, bacterial, or fungal)

- Ischemic colitis

- Intestinal obstruction

Complications

Paracentesis is a safe procedure; however, complications are possible.[27] They include the following:

- Persistent leakage of ascitic fluid at the needle insertion site

- This issue can often be addressed with a single skin suture.

- Abdominal wall hematoma or bleeding

- Wound infection

- Perforation of surrounding vessels or viscera (extremely rare)

- Hypotension after large volume fluid removal (more than 5-6 L)

- Spontaneous hemoperitoneum

- Catheter laceration and loss in the abdominal cavity

- Hepatorenal syndrome [29]

- Subcutaneous effusion due to ascitic fluid leakage [30]

The evidence supporting colloid replacement after large-volume paracentesis (LVP) is mixed and of lower quality. However, several studies have demonstrated decreased hypotension after paracentesis if albumin is administered when more than 5 L of fluid is removed.[14][28][31][32][28] Around 6 to 8 g of 25% albumin/L of fluid should be administered within 1 hour of LVP.[28] In patients with SBP, in addition to empiric antibiotics, 25% albumin should be administered in patients without hypoxia, pulmonary edema, end-stage renal disease, and decompensated heart failure at a dose of 1.5 g/kg body weight, to prevent acute kidney injury (AKI) and hepatorenal syndrome. Albumin administration in patients with SBP lowered the risk of AKI (8 vs 31%, odds ratio of 0.21) and mortality (16% vs 35% OR 0.34%).[26][33]

Clinical Significance

The development of fluid in the peritoneal space, known as ascites, can occur due to many different disease states. Performing a paracentesis will help determine the etiology of a patient's ascites. Draining the peritoneal fluid may help identify infection, causes of liver disease, or portal hypertension and relieve symptoms by removing a large volume of fluid. Using bedside ultrasound to identify an ideal pocket of fluid will increase the likelihood of a successful procedure. According to the results of a retrospective study of 97 patients, early paracentesis can decrease mortality rates in cases of SBP.[34] The study showed that emergency clinicians often ordered early paracentesis.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Optimal performance of paracentesis requires a combination of technical skills, evidence-based strategies, and effective interprofessional collaboration to ensure safety and improved outcomes. Physicians and advanced practitioners must demonstrate procedural proficiency, including patient selection, anatomical knowledge, ultrasound-guided technique, and peritoneal fluid interpretation. Nurses play a critical role in preparation, patient positioning, monitoring vital signs, and providing postprocedure care. Pharmacists contribute by ensuring the timely initiation of empiric antibiotics in suspected spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and guiding appropriate albumin replacement after large-volume paracentesis. Advanced clinical providers and trainees also require structured supervision to develop procedural competency while maintaining patient safety.

High-quality patient care during paracentesis is enhanced by clear interprofessional communication and coordinated workflows. Preprocedure discussions between providers ensure informed consent and patient education. At the same time, real-time collaboration during the procedure supports sterility and safety. Postprocedure, coordination among the care team allows for timely review of ascitic fluid results, early identification of complications, and rapid initiation of targeted therapies. By leveraging the expertise of multiple disciplines, healthcare teams can minimize complications, enhance patient safety, and optimize both immediate and long-term outcomes for patients with ascites requiring paracentesis.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

Competence and proficiency in performing paracentesis and other procedures should be monitored at predetermined intervals. Analysing complication rates for individual operators helps decrease adverse events and improve safety and quality.[20] The infection control and prevention department and healthcare systems' patient safety and quality departments can perform this.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

Patients need close monitoring by nursing during and after the procedure, as it can be associated with hypotension, tachycardia, hemorrhage, fluid leakage, infection, and bowel perforation.[35][36] They can then communicate any untoward signs or symptoms to the physician so that appropriate action can be taken.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Ong JP. Paracentesis. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2006 Sep:101(9):1954-5 [PubMed PMID: 16968501]

Runyon BA, AASLD Practice Guidelines Committee. Management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis: an update. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.). 2009 Jun:49(6):2087-107. doi: 10.1002/hep.22853. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19475696]

Kim JJ, Tsukamoto MM, Mathur AK, Ghomri YM, Hou LA, Sheibani S, Runyon BA. Delayed paracentesis is associated with increased in-hospital mortality in patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2014 Sep:109(9):1436-42. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.212. Epub 2014 Aug 5 [PubMed PMID: 25091061]

Aithal GP, Palaniyappan N, China L, Härmälä S, Macken L, Ryan JM, Wilkes EA, Moore K, Leithead JA, Hayes PC, O'Brien AJ, Verma S. Guidelines on the management of ascites in cirrhosis. Gut. 2021 Jan:70(1):9-29. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321790. Epub 2020 Oct 16 [PubMed PMID: 33067334]

Fleming KM, Aithal GP, Card TR, West J. The rate of decompensation and clinical progression of disease in people with cirrhosis: a cohort study. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2010 Dec:32(11-12):1343-50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04473.x. Epub 2010 Oct 4 [PubMed PMID: 21050236]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCho J, Jensen TP, Reierson K, Mathews BK, Bhagra A, Franco-Sadud R, Grikis L, Mader M, Dancel R, Lucas BP, Society of Hospital Medicine Point-of-care Ultrasound Task Force, Soni NJ. Recommendations on the Use of Ultrasound Guidance for Adult Abdominal Paracentesis: A Position Statement of the Society of Hospital Medicine. Journal of hospital medicine. 2019 Jan 2:14():E7-E15. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3095. Epub 2019 Jan 2 [PubMed PMID: 30604780]

Sakai H, Sheer TA, Mendler MH, Runyon BA. Choosing the location for non-image guided abdominal paracentesis. Liver international : official journal of the International Association for the Study of the Liver. 2005 Oct:25(5):984-6 [PubMed PMID: 16162157]

Thomsen TW, Shaffer RW, White B, Setnik GS. Videos in clinical medicine. Paracentesis. The New England journal of medicine. 2006 Nov 9:355(19):e21 [PubMed PMID: 17093242]

Bureau C, Adebayo D, Chalret de Rieu M, Elkrief L, Valla D, Peck-Radosavljevic M, McCune A, Vargas V, Simon-Talero M, Cordoba J, Angeli P, Rosi S, MacDonald S, Malago M, Stepanova M, Younossi ZM, Trepte C, Watson R, Borisenko O, Sun S, Inhaber N, Jalan R. Alfapump® system vs. large volume paracentesis for refractory ascites: A multicenter randomized controlled study. Journal of hepatology. 2017 Nov:67(5):940-949. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.06.010. Epub 2017 Jun 21 [PubMed PMID: 28645737]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAllen R, Sarani B. Evaluation and management of intraabdominal hypertension. Current opinion in critical care. 2020 Apr:26(2):192-196. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000701. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32004192]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWittmer VL, Lima RT, Maia MC, Duarte H, Paro FM. RESPIRATORY AND SYMPTOMATIC IMPACT OF ASCITES RELIEF BY PARACENTESIS IN PATIENTS WITH HEPATIC CIRRHOSIS. Arquivos de gastroenterologia. 2020 Jan-Mar:57(1):64-68. doi: 10.1590/S0004-2803.202000000-11. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32294737]

Ota KS, Schultz N, Segaline NA. Palliative Paracentesis in the Home Setting: A Case Series. The American journal of hospice & palliative care. 2021 Aug:38(8):1042-1045. doi: 10.1177/1049909120963075. Epub 2020 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 32996326]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKunin M, Mini S, Abu-Amer N, Beckerman P. Regular at-home abdominal paracentesis via Tenckhoff catheter in patients with refractory congestive heart failure. International journal of clinical practice. 2021 Dec:75(12):e14924. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.14924. Epub 2021 Oct 5 [PubMed PMID: 34581465]

McGibbon A, Chen GI, Peltekian KM, van Zanten SV. An evidence-based manual for abdominal paracentesis. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2007 Dec:52(12):3307-15 [PubMed PMID: 17393312]

McVay PA, Toy PT. Lack of increased bleeding after paracentesis and thoracentesis in patients with mild coagulation abnormalities. Transfusion. 1991 Feb:31(2):164-71 [PubMed PMID: 1996485]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTripodi A, Mannucci PM. The coagulopathy of chronic liver disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2011 Jul 14:365(2):147-56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1011170. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21751907]

Grabau CM, Crago SF, Hoff LK, Simon JA, Melton CA, Ott BJ, Kamath PS. Performance standards for therapeutic abdominal paracentesis. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.). 2004 Aug:40(2):484-8 [PubMed PMID: 15368454]

Bard C, Lafortune M, Breton G. Ascites: ultrasound guidance or blind paracentesis? CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 1986 Aug 1:135(3):209-10 [PubMed PMID: 3524781]

Patel PA, Ernst FR, Gunnarsson CL. Evaluation of hospital complications and costs associated with using ultrasound guidance during abdominal paracentesis procedures. Journal of medical economics. 2012:15(1):1-7. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2011.628723. Epub 2011 Oct 19 [PubMed PMID: 22011070]

Suh MI, Preiksaitis C, Chen E. Beyond the numbers: Reimagining procedural proficiency in emergency medicine residencies. AEM education and training. 2023 Dec:7(6):e10920. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10920. Epub 2023 Nov 29 [PubMed PMID: 38046092]

Millington SJ, Koenig S. Better With Ultrasound: Paracentesis. Chest. 2018 Jul:154(1):177-184. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.03.034. Epub 2018 Apr 7 [PubMed PMID: 29630894]

Nazeer SR, Dewbre H, Miller AH. Ultrasound-assisted paracentesis performed by emergency physicians vs the traditional technique: a prospective, randomized study. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2005 May:23(3):363-7 [PubMed PMID: 15915415]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKelil T, Shyn PB, Wu LE, Levesque VM, Kacher D, Khorasani R, Silverman SG. Wall suction-assisted image-guided therapeutic paracentesis: a safe and less expensive alternative to evacuated bottles. Abdominal radiology (New York). 2016 Jul:41(7):1333-7. doi: 10.1007/s00261-016-0634-x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27315094]

Hoefs JC. Serum protein concentration and portal pressure determine the ascitic fluid protein concentration in patients with chronic liver disease. The Journal of laboratory and clinical medicine. 1983 Aug:102(2):260-73 [PubMed PMID: 6864073]

Bunchorntavakul C, Chamroonkul N, Chavalitdhamrong D. Bacterial infections in cirrhosis: A critical review and practical guidance. World journal of hepatology. 2016 Feb 28:8(6):307-21. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v8.i6.307. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26962397]

Sort P, Navasa M, Arroyo V, Aldeguer X, Planas R, Ruiz-del-Arbol L, Castells L, Vargas V, Soriano G, Guevara M, Ginès P, Rodés J. Effect of intravenous albumin on renal impairment and mortality in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. The New England journal of medicine. 1999 Aug 5:341(6):403-9 [PubMed PMID: 10432325]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRunyon BA. Paracentesis of ascitic fluid. A safe procedure. Archives of internal medicine. 1986 Nov:146(11):2259-61 [PubMed PMID: 2946271]

De Gottardi A, Thévenot T, Spahr L, Morard I, Bresson-Hadni S, Torres F, Giostra E, Hadengue A. Risk of complications after abdominal paracentesis in cirrhotic patients: a prospective study. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2009 Aug:7(8):906-9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.05.004. Epub 2009 May 15 [PubMed PMID: 19447197]

Duggal P, Farah KF, Anghel G, Marcus RJ, Lupetin AR, Babich MM, Sandroni SE, McGill RL. Safety of paracentesis in inpatients. Clinical nephrology. 2006 Sep:66(3):171-6 [PubMed PMID: 16995339]

Otsuka Y, Nagaoka H, Nakano Y, Sakae H, Hasegawa K, Otsuka F. Subcutaneous edema as rare complication of abdominal paracentesis. Clinical case reports. 2021 Nov:9(11):e05116. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.5116. Epub 2021 Nov 19 [PubMed PMID: 34824856]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLuca A, García-Pagán JC, Bosch J, Feu F, Jiménez W, Ginés A, Fernández M, Escorsell A, Arroyo V, Rodés J. Beneficial effects of intravenous albumin infusion on the hemodynamic and humoral changes after total paracentesis. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.). 1995 Sep:22(3):753-8 [PubMed PMID: 7657279]

Ginès A, Fernández-Esparrach G, Monescillo A, Vila C, Domènech E, Abecasis R, Angeli P, Ruiz-Del-Arbol L, Planas R, Solà R, Ginès P, Terg R, Inglada L, Vaqué P, Salerno F, Vargas V, Clemente G, Quer JC, Jiménez W, Arroyo V, Rodés J. Randomized trial comparing albumin, dextran 70, and polygeline in cirrhotic patients with ascites treated by paracentesis. Gastroenterology. 1996 Oct:111(4):1002-10 [PubMed PMID: 8831595]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBelcher JM, Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Bhogal H, Lim JK, Ansari N, Coca SG, Parikh CR, TRIBE-AKI Consortium. Association of AKI with mortality and complications in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.). 2013 Feb:57(2):753-62. doi: 10.1002/hep.25735. Epub 2012 Dec 6 [PubMed PMID: 22454364]

Abdu B, Akolkar S, Picking C, Boura J, Piper M. Factors Associated with Delayed Paracentesis in Patients with Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2021 Nov:66(11):4035-4045. doi: 10.1007/s10620-020-06750-0. Epub 2020 Dec 3 [PubMed PMID: 33274417]

Ning S, Yang Y, Wang C, Luo F. Pseudomyxoma peritonei induced by low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm accompanied by rectal cancer: a case report and literature review. BMC surgery. 2019 Apr 25:19(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s12893-019-0508-6. Epub 2019 Apr 25 [PubMed PMID: 31023277]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJun Jie NG, Teo KA, Shabbir A, Yeo TT. Widespread Intra-abdominal Carcinomatosis from a Rhabdoid Meningioma after Placement of a Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Asian journal of neurosurgery. 2018 Jan-Mar:13(1):176-183. doi: 10.4103/1793-5482.181128. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29492156]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence