Introduction

Plaque psoriasis, also known as psoriasis vulgaris, is a chronic, immune-mediated inflammatory skin disorder characterized by well-demarcated, erythematous plaques covered with silvery-white scales (see Image. Plaque Psoriasis: Multiple Erythematous Scaly Plaques Over the Back). Plaque psoriasis is the most prevalent form of psoriasis, accounting for approximately 80% to 90% of all psoriasis cases. This disorder is typically a lifelong relapsing-remitting condition, with flares often triggered by infections, stress, medications, or trauma. Some patients may experience stable disease with minimal symptoms, whereas others develop severe, widespread plaques that significantly impair their quality of life.

Plaque psoriasis most commonly affects the extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees, the scalp, the trunk, and the lumbosacral region; it can also appear on the nails and intertriginous areas. In some cases, it may progress to involve the joints, manifesting as psoriatic arthritis, or be associated with systemic inflammatory comorbidities such as metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and depression. Early recognition and comprehensive management are crucial to mitigate disease burden and long-term complications.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The etiology of psoriasis is multifactorial, involving genetic, immunologic, and environmental factors. Although the precise cause remains incompletely understood, the condition is widely recognized as an immune-mediated disorder that triggers symptoms in genetically predisposed individuals.

Genetics plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Up to 40% of patients report a positive family history. Multiple susceptibility loci have been identified, with PSORS1 on chromosome 6p21 being the most significant. This region includes the HLA-Cw6 allele, strongly associated with early-onset and more severe disease phenotypes.[1]

Several environmental and lifestyle factors are known to precipitate or exacerbate psoriasis in susceptible individuals:

- Infections, especially streptococcal pharyngitis, where oligoclonal expansion of T cells occurs in the tonsils in response to streptococcal colonisation, and the same T-cell repertoire may be found in the peripheral blood and skin

- Trauma or skin injury (Koebner phenomenon) (see Image. True Koebner Phenomenon in a Patient With Chronic Plaque Psoriasis)

- Stress and psychological factors

- Medications such as beta-blockers, lithium, antimalarials, and immune checkpoint inhibitors (eg, pembrolizumab) [2]

- Abrupt withdrawal of corticosteroids

- Smoking and alcohol use

- Obesity and metabolic syndrome

Epidemiology

Psoriasis is a global chronic inflammatory disease with substantial variation in prevalence by age, sex, and geography. Overall, psoriasis affects nearly 3% of adults in the United States and has a significant global burden, with variation influenced by geography, ethnicity, diagnostic criteria, and environmental factors.[3]

According to the Global Psoriasis Atlas systematic review, the estimated global lifetime prevalence in adults is 0.59%, equating to about 29.5 million affected adults.[4]

The age distribution indicates that psoriasis is primarily a disease of adults, with a prevalence ranging from 0.14% to 3%, depending on the region. In contrast, the prevalence among children is significantly lower, ranging from 0.02% in East Asia to 0.21% in Western Europe and Australasia. There is a bimodal age of onset, with the first peak occurring before 35 and a second peak in middle age. The sex distribution does not follow a consistent global pattern; studies show considerable variability, with some reporting slightly higher rates in women and others indicating a male predominance.

Pathophysiology

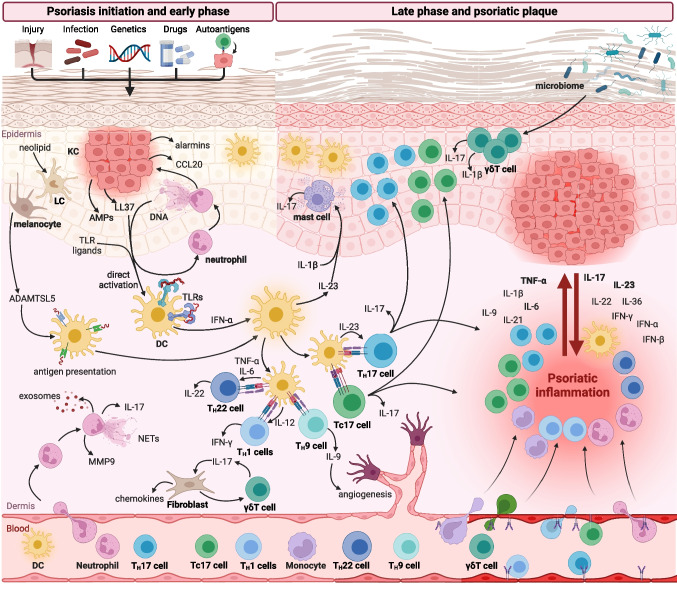

Plaque psoriasis is an immune-mediated inflammatory disorder characterized by hyperproliferation and abnormal differentiation of keratinocytes, driven by dysregulated interactions between the innate and adaptive immune systems (see Image. Pathogenesis of Psoriasis).[5]

The process begins with antigen-presenting cells, such as Langerhans cells, activating T cells in regional lymph nodes. These T cells return to the skin, where they secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines, centered around the interleukin (IL)-23/IL-17 axis and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) pathways, particularly the TNF-α pathway, promoting a chronic inflammatory response. This inflammation results in the recruitment of additional immune cells, such as dendritic cells, neutrophils, and macrophages, to the dermis and epidermis, amplifying the cycle.[6]

Keratinocytes respond to these cytokines with rapid proliferation, causing epidermal thickening (ie, acanthosis), parakeratosis (ie, retention of nuclei in the stratum corneum), and impaired differentiation. The accelerated cell turnover (3-5 days versus 28-30 days in normal skin) and decreased lipid secretion lead to characteristic scaly plaques. Vascular changes, including superficial blood vessel dilation and neovascularization, also contribute to the lesion's appearance. The chronicity of plaque psoriasis is maintained by ongoing crosstalk between immune cells and keratinocytes, sustaining a vicious cycle of inflammation and skin remodeling. Persistent resident memory T cells explain the recurrence of plaques at the same sites.

Histopathology

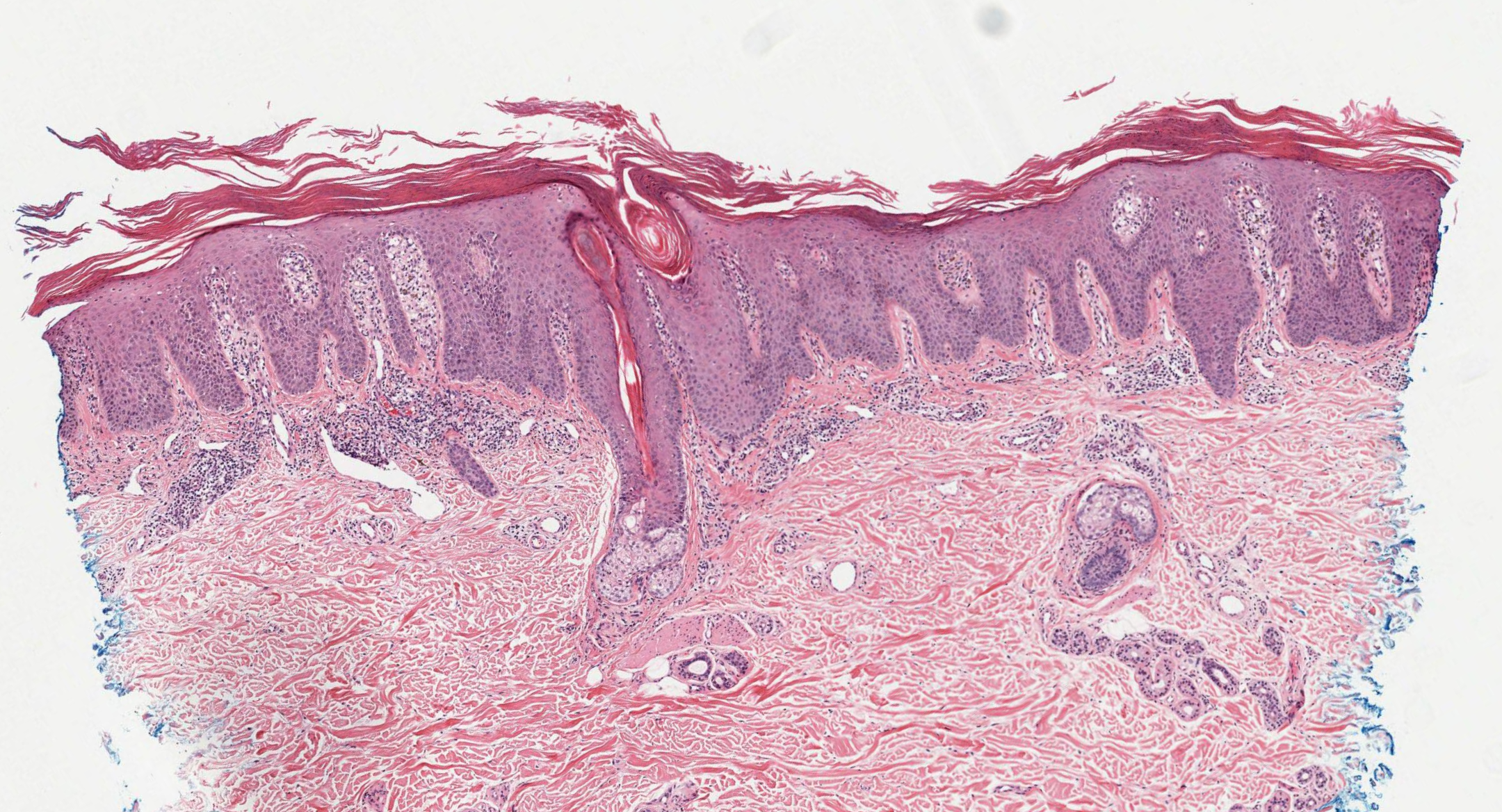

In early lesions, vasodilation, papillary dermal edema, and leukocyte infiltration precede epidermal changes. These changes are followed by compact hyperkeratosis, loss of the granular layer, epidermal hyperplasia, and focal parakeratosis. Dilated, tortuous papillary capillaries with mixed inflammatory infiltrates are prominent.

Fully developed plaques demonstrate parakeratosis with focal orthokeratosis, near absence of the granular layer, elongated and clubbed rete ridges, and suprapapillary epidermal thinning. Munro microabscesses and mixed dermal infiltrates of lymphocytes and neutrophils are common, along with dilated papillary vessels and occasional necrotic keratinocytes (see Image. Psoriasis Dermpath).

History and Physical

Patients with plaque psoriasis typically report a chronic, relapsing-remitting course of scaly skin lesions.

On examination, the hallmark finding is symmetrically distributed, well-demarcated, erythematous plaques with loosely adherent, dry, silvery-white scales, most commonly affecting the extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees, scalp, and lumbosacral region.

Psoriatic lesions are sometimes surrounded by a pale blanching ring, which is commonly known as Woronoff's ring. The characteristic triad of erythema, thickening, and scaling in plaque psoriasis corresponds to underlying histopathologic changes, including dilated superficial capillaries, epidermal acanthosis with inflammatory infiltrates, and disordered keratinization.

When the micaceous, silvery-white scales are gently removed, a moist surface with pinpoint bleeding (Auspitz sign) is observed, reflecting elongated dermal papillary vessels beneath a thinned suprapapillary epidermis. Exacerbations are often accompanied by pruritus, and the appearance of tiny papules at the periphery of plaques indicates disease instability.

Actively spreading lesions typically show a brightly erythematous advancing edge, whereas involution often begins centrally, creating annular configurations (see Image. Psoriasis: Annular Erythematous Plaques on the Arm).

Plaques can persist for months to years at the exact locations. In contrast, periods of complete remission do occur, and remissions lasting for at least 5 years have been reported in nearly 15% of patients. Linear and geometric configurations may arise at the sites of trauma as an isomorphic (Koebner) phenomenon.

Nail changes are common, including pitting, onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, and oil-drop discoloration, the latter of which is often described as a salmon patch appearance. Nail involvement is a strong predictor of concomitant psoriatic arthritis (see Image. Nails in Psoriasis).

Evaluation

The diagnosis of plaque psoriasis is primarily clinical, based on history and physical examination. A skin biopsy may occasionally be helpful in atypical cases to rule out notoriously similar pathologies. Routine laboratory or radiographic testing is not typically required for classic presentations. However, additional studies may be warranted to assess disease severity, exclude mimicking conditions, or evaluate systemic involvement.

Laboratory tests may include complete blood counts, liver and renal function tests, and lipid or glucose profiles, particularly before and during systemic therapies, such as methotrexate, cyclosporine, acitretin, and biologics.

Screening for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, HIV, and tuberculosis (eg, purified protein derivative, T-Spot, or QuantiFERON Gold) is recommended before initiating biologic or immunosuppressive therapy in accordance with American Academy of Dermatology guidelines. A noninvasive baseline assessment of liver fibrosis is recommended before initiating methotrexate. Baseline and biweekly blood urea nitrogen and creatinine monitoring are recommended during the first 3 months of treatment, followed by monthly monitoring thereafter with cyclosporine. Baseline fasting lipid profile and pregnancy test are essential for women of childbearing potential before starting acitretin.[7]

Radiographic evaluation is not necessary for cutaneous disease but is indicated when psoriatic arthritis is suspected. Plain radiographs may reveal erosions, joint space narrowing, or new bone formation, whereas ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging can detect early synovitis and enthesitis.

Other tools include validated disease severity indices such as the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI), Body Surface Area (BSA) involvement, and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), which help guide therapy and monitor response.[8]

Treatment / Management

The management of plaque psoriasis is individualized, guided by disease severity, body surface area (BSA) involvement, impact on quality of life, and comorbidities. Treatment goals include reducing lesion burden, alleviating symptoms, improving quality of life, and preventing systemic complications.

Topical therapy is first-line for mild disease (BSA <5%). Common agents include topical corticosteroids, vitamin D analogs, retinoids, coal tar, anthralin, salicylic acid, TNF-α inhibitors, IL-12/23 inhibitors, IL-17 inhibitors, and IL-23 inhibitors.

Topical Corticosteroids

The selection of a topical corticosteroid should consider disease severity, anatomical site, patient preference, and age. Low-potency agents are preferred for sensitive areas such as the face, flexures, and thin-skinned regions prone to atrophy. For most adults, moderate-to-high potency corticosteroids (classes 2-5) are suitable as first-line therapy, whereas ultra-high potency agents (class 1) are reserved for thick, chronic plaques. The most frequent local adverse effects of topical corticosteroids include skin atrophy, striae, folliculitis, telangiectasia, and purpura, with the face, flexures, and chronically treated thin-skinned areas being most susceptible (see Image. Striae Atrophicans Due to Potent Topical Corticosteroid Application to Axilla).

These corticosteroids may also exacerbate acne, rosacea, perioral dermatitis, tinea infections, or, in rare cases, induce contact dermatitis. Sudden discontinuation can lead to rebound flares, although their frequency is uncertain. To minimize risks, class 1 corticosteroids are generally limited to twice daily use for up to 4 weeks. Proactive therapy is a useful long-term strategy in which clinically quiescent but recurrent sites are treated twice weekly to reduce relapse rates.[9]

Vitamin D Analogs

Vitamin D analogs, such as calcipotriene and calcitriol, improve psoriasis by reducing keratinocyte proliferation and promoting differentiation. These agents are generally safe, with local irritation—such as burning, pruritus, or erythema—affecting up to one-third of patients but often resolves over time. Rare systemic effects, such as hypercalcemia and parathyroid hormone suppression, occur mainly with excessive dosing or renal impairment.

Retinoids

Tazarotene is a topical retinoid used for mild-to-moderate psoriasis, improving lesions within 8 to 12 weeks by regulating keratinocyte proliferation and inflammation. Common adverse effects include erythema, burning, and pruritus, which can be minimized with combination therapy or alternate application. Use is contraindicated during pregnancy and requires careful counseling in women of childbearing age.

Coal Tar

Coal tar, a long-standing therapy for mild-to-moderate psoriasis, inhibits keratinocyte proliferation and reduces inflammation. Clinical trials confirm its efficacy alone or when combined with narrowband UVB (Goeckerman therapy). Adverse effects include irritation, folliculitis, and phototoxicity; carcinogenic risk remains unproven. Use is generally avoided during pregnancy and lactation.[10](B3)

Anthralin

Anthralin is a topical agent for mild-to-moderate psoriasis that inhibits T-cell activation and promotes keratinocyte differentiation. Used in short-contact therapy (up to 2 h), it improves lesions within 8 to 12 weeks. Adverse effects include erythema, burning, and skin staining; use on the face and flexures should be avoided.

Salicylic Acid

Salicylic acid is useful both as monotherapy and when used in conjunction with topical corticosteroids.

Combination regimens, such as corticosteroids with vitamin D analogs, are more effective and reduce adverse effects.

Phototherapy is recommended for patients with inadequate response to topicals or with more widespread disease. Narrowband UVB is preferred for efficacy or safety; broadband UVB and excimer (308 nm) are alternatives for localized plaques. PUVA is effective but less favored due to its cumulative phototoxicity and carcinogenic risk; therefore, eye and skin protection, as well as tracking of cumulative dose, are required.

Systemic non-biologic therapy is appropriate for moderate-to-severe disease (BSA >10%, PASI >10), rapid flares, or special sites (nails, scalp, palms, or soles), and as a bridging therapy to biologics. Methotrexate remains a cornerstone therapy; it should be accompanied by folate supplementation, with regular monitoring of CBC, liver and renal function, and pregnancy testing. Cyclosporine provides rapid control for severe, unstable, erythrodermic, or pustular psoriasis but is time-limited by nephrotoxicity and hypertension.

Acitretin is effective for keratoderma and pustular psoriasis phenotypes; however, its teratogenicity necessitates strict avoidance of pregnancy for up to three years following treatment. Oral alternatives include targeted small molecules such as apremilast—a PDE4 inhibitor—and JAK inhibitors, such as deucravacitinib and tofacitinib. Apremilast offers a favorable safety profile, primarily limited to gastrointestinal symptoms and weight loss, and requires minimal laboratory monitoring.

Biologics are highly effective for moderate-to-severe psoriasis, offering durable clearance and an improved quality of life. The 2023 British Academy of Dermatology update recommends TNF-α inhibitors, IL-17 inhibitors, IL-12/23 inhibitors, and IL-23 inhibitors as first-line biologics, with class choice guided by efficacy, comorbidities, and safety profile. IL-17 and IL-23 inhibitors offer rapid, high-level skin clearance and durable responses, whereas ustekinumab (IL-12/23) and TNF inhibitors remain preferred in patients with psoriatic arthritis or specific comorbidities.[11]

TNF-α Inhibitors

- Adalimumab: 80 mg subcutaneous (SC) once, then 40 mg every other week.

- Etanercept: 50 mg SC twice weekly for 12 weeks, then 50 mg weekly.

- Infliximab: 5 mg/kg intravenous at weeks 0, 2, and 6, then every 8 weeks.

- Certolizumab pegol: 400 mg SC at weeks 0, 2, and 4, then 200 mg every 2 weeks or 400 mg every 4 weeks.[12] (A1)

IL-12/23 Inhibitor

-

Ustekinumab: For patients weighing <100 kg, 45 mg SC at weeks 0 and 4, then every 12 weeks; For those weighing ≥100 kg, 90 mg at the same schedule.

IL-17 Inhibitors

- Secukinumab: 300 mg SC weekly for 5 weeks, then every 4 weeks.

- Ixekizumab: 160 mg SC once, then 80 mg every 2 weeks through week 12, then every 4 weeks.

- Brodalumab: 210 mg SC at weeks 0, 1, and 2, then every 2 weeks (boxed warning for suicidality).[13] (B2)

IL-23 Inhibitors

Differential Diagnosis

Diagnosis is typically clinical; however, atypical morphology, special sites, or treatment-refractory plaques warrant a structured differential diagnosis and, occasionally, biopsy.

Classic plaque psoriasis should be differentiated from several mimics as follows:

- Seborrheic dermatitis: Less sharply demarcated plaques with a dull or greasy, branny scale

- Chronic eczema or lichen simplex chronicus: Ill-defined borders, lichenification, and intense pruritus

- Lichen planus: Violaceous hue, Wickham striae, and oral lesions

In cases of atrophic, wrinkled, or nonresponsive plaques, porokeratosis (characterized by cornoid lamella), Bowen disease or erythroplasia of Queyrat (typically solitary lesions requiring biopsy to exclude squamous cell carcinoma in situ), and mycosis fungoides should be considered. Dermatomyositis may mimic scalp, elbow, or knee involvement.

Flexural or intertriginous disease overlaps with candidiasis (satellite pustules), tinea incognito, erythrasma (coral-red on Wood's lamp), seborrheic and allergic or irritant contact dermatitis, and extramammary Paget disease. KOH wet mount preparation and culture should be performed when fungal infection is possible; note that candidiasis and psoriasis may coexist.

Palmoplantar disease can resemble hyperkeratotic hand or foot eczema; sharply marginated plaques favor psoriasis. Dermatophyte infection and secondary infection should be ruled out in palmoplantar pustulosis and acrodermatitis continua (see Image. Plantar Psoriasis: Isolated Hyperkeratotic Scaly Plaque With Fissuring Over the Sole).

Guttate psoriasis must be differentiated from pityriasis lichenoides chronica, small-plaque parapsoriasis, secondary syphilis (serology, mucosal lesions, and palm or sole involvement), pityriasis rosea, and tinea corporis (annular edge and positive mycology).

Although psoriasis may have an expansive differential, coexistence with other conditions, such as seborrheic dermatitis, lichen simplex chronicus, or contact dermatitis via koebnerization, is common. For limited, treatment-resistant plaques, a biopsy should be obtained to exclude squamous cell carcinoma in situ or cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. When arthritis accompanies psoriasiform eruptions, evaluation for reactive arthritis is warranted.

Prognosis

Plaque psoriasis is generally a chronic, relapsing disease with variable clinical courses. In many patients, lesions persist for years with minimal change, whereas others experience fluctuating severity influenced by environmental triggers. Spontaneous remission may occur in up to one-third of patients, though relapse is common without treatment. Modern systemic and biologic therapies can maintain prolonged remission, but discontinuation often leads to recurrence, with relapse timing varying widely among individuals and treatment modalities. Patients with severe plaque psoriasis have a reduced life expectancy by an estimated 4 to 6 years, largely due to comorbid cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and systemic inflammation. In addition, all treatments have significant adverse effects, including skin cancers, liver damage, and susceptibility to infections. The most significant morbidity is from poor aesthetics, which can cause depression, isolation, and withdrawal from society.

Complications

Psoriasis can lead to complications involving multiple organ systems.

- Cutaneous complications include painful fissuring, erythroderma, and pustular flares, which can be life-threatening due to impaired thermoregulation, dehydration, or sepsis. Chronic scratching may lead to lichenification or Koebnerization at sites of trauma.

- Articular complications occur in up to 20% to 30% of patients with psoriatic arthritis, characterized by enthesitis, dactylitis, and progressive joint damage if untreated (see Image. Arthritis Mutilans).[15]

- Systemic comorbidities include metabolic syndrome, obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and cardiovascular disease, contributing to increased risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and reduced life expectancy. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is also common, present in up to 50% patients with psoriasis.[16]

- Ophthalmologic manifestations, such as uveitis and conjunctivitis, may occur, particularly in individuals with psoriatic arthritis.[17]

- Psychiatric complications include depression, anxiety, alcohol misuse, dysfunctional thought, pathological worrying, fear of stigmatisation, alexithymia, effects on self-image, personality, and temperament, and increased risk of suicidal ideation, reflecting the high psychosocial burden.[18]

- Treatment-related complications must also be considered. Methotrexate can cause hepatotoxicity and myelosuppression, cyclosporine may lead to nephrotoxicity and hypertension, acitretin is teratogenic, and biologic agents increase the risk of infections.[19][20]

Consultations

Effective care for psoriasis is interprofessional, requiring coordination and referrals tailored to disease presentation, comorbidities, and treatment plans.

- Dermatology: Diagnostic uncertainty; atypical, erythrodermic, or pustular variants; moderate-to-severe disease (eg, BSA >10%, PASI >10, or DLQI >10); phototherapy candidacy; initiation or failure of systemic or biologic therapy.

- Rheumatology: Suspected psoriatic arthritis (eg, inflammatory back pain, enthesitis, dactylitis, morning stiffness, and nail disease); joint damage risk; biologic selection when joint disease predominates.

- Primary care or internal medicine: Longitudinal comorbidity screening and risk-factor modification (eg, obesity, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, smoking, and alcohol).

- Cardiology or endocrinology: High cardiometabolic risk or established disease and optimization before systemic therapy.

- Hepatology: Preexisting liver disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, alcohol use, or methotrexate monitoring or clearance concerns.

- Nephrology: Cyclosporine use or chronic kidney disease.

- Infectious diseases: Positive tuberculosis, hepatitis B or C, or HIV screening; recurrent or opportunistic infections on immunomodulators.

- Psychiatry or psychology: Depression, anxiety, substance use, suicidal ideation, and adherence support.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Effective management of plaque psoriasis requires patient-centered education to reduce triggers, prevent flares, and promote safe, sustained treatment. Counseling should be practical, concise, and reinforced by the interprofessional team.

Preventing Flares

- Trigger avoidance: Identify and avoid common triggers such as streptococcal infections, skin trauma (Koebner phenomenon), emotional stress, heavy alcohol use, smoking, and certain medications, such as lithium, beta-blockers, and abrupt systemic corticosteroid withdrawal.

- Sun exposure: Encourage moderate, safe sun exposure; brief supervised UV exposure can improve lesions, but caution against sunburn. Discuss phototherapy options with dermatology if appropriate.

- Lifestyle modification: Promote weight reduction and regular exercise, which reduce systemic inflammation and improve response to therapy in overweight patients.

- Skin care: Use emollients liberally to restore barrier function, avoid harsh soaps, and promptly treat secondary infections.

Medication and Treatment Education

- Explain expected timeframes for response to topical, phototherapy, systemic, and biologic therapies and set realistic goals, such as reduction in itching and plaque thickness.

- Emphasize adherence, correct topical application (thin layer; vehicles for scalp vs body), and safer intermittent or maintenance schedules for potent corticosteroids.

- Review medication safety: Need for baseline labs and periodic monitoring for methotrexate, cyclosporine, and acitretin; contraception requirements with acitretin; infection risk and vaccination timing with biologics or immunomodulators; and need for early morning resting blood pressure monitoring for cyclosporine.

- Advise patients on when to stop therapy and seek urgent care if they develop new widespread pustules, fever, signs of systemic infection, rapidly progressive erythroderma, or severe medication adverse effects.

Psychosocial Support and Self-Management

- Screen for depression, anxiety, and alcohol misuse; offer referral to mental health services and support groups. Discuss realistic expectations about cosmetic and social impacts.

- Provide written action plans, including a trigger log, treatment schedule, contact information for the care team, and criteria for urgent evaluation.

- Offer educational resources (eg, patient-friendly materials, National Psoriasis Foundation, and local support groups) and involve pharmacists for counseling on interactions and adherence aids.

Follow-up and Coordination

-

Arrange regular follow-up to reassess severity (BSA, PASI, and DLQI), monitor for comorbidities (cardiometabolic disease and psoriatic arthritis), and adjust therapy. Empower the patient to be an active partner in long-term disease control through lifestyle changes, adherence, and timely communication with the interprofessional team.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Plaque psoriasis is a chronic, multisystem inflammatory disease that requires coordinated, patient-centered care to reduce skin and joint morbidity, identify and manage cardiometabolic and psychiatric comorbidities, and safely use systemic and biologic therapies. Optimal outcomes depend on accurate assessment of severity (BSA, PASI, and DLQI), guideline-based treatment selection, proactive safety monitoring (laboratory tests, tuberculosis or hepatitis screening, and immunization review), and longitudinal follow-up to adjust therapy and address lifestyle factors. Because psoriasis affects quality of life, occupational functioning, and mental health, the care plan must integrate medical, psychosocial, and preventive care goals.

A high-performing interprofessional team leverages each member's expertise. Clinicians and dermatology specialists determine diagnosis, severity staging, and the initial treatment strategy; obtain informed consent for risks and benefits, and coordinate referrals (rheumatology, cardiology, and obstetrics). Advanced practice providers extend access by managing routine follow-ups, titrating therapies per protocols, and providing patient education. Nurses play a central role in triage, administration of phototherapy or biologics, injection teaching, wound or fissure care, monitoring adverse effects, and screening for psychosocial distress. Pharmacists review drug-drug interactions (eg, CYP3A4 issues with cyclosporine), counsel on adherence and contraception (acitretin), manage specialty pharmacy navigation for biologics, and support medication safety monitoring. Rheumatologists, cardiologists, endocrinologists, hepatologists, and infectious disease specialists co-manage comorbid conditions or pretherapy clearance. Mental health clinicians, social workers, dietitians, and physical or occupational therapists address depression, lifestyle modification, weight management, and functional limitations from arthritis.

Practical team strategies to improve care and safety include standardized care pathways and treatment algorithms; pre-biologic checklists (eg, vaccinations, tuberculosis or hepatitis screening, and baseline labs); scheduled multidisciplinary case reviews for complex patients; shared documentation and problem lists to reduce fragmentation; and defined referral triggers (new joint pain, uncontrolled BSA or PASI, and suicidal ideation). Regular team huddles, delegated standing orders (eg, baseline labs and vaccination administration), and care coordinators or nurse navigators reduce delays and improve adherence.

Ethical responsibilities include ensuring informed, shared decision-making, transparency about costs and access barriers, equitable therapy selection, and respect for patient autonomy—particularly when balancing teratogenic risks, infection risk with immunosuppression, or trade-offs between efficacy and adverse effects. Documentation of counseling, contraception plans when indicated, and mental health screening protects patient safety and supports ethical care.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Pathogenesis of Psoriasis. Triggers such as trauma, infection, drugs, or autoantigens activate neutrophils, keratinocytes, and dendritic cells, initiating T-cell–driven inflammation. Activated TH17, TH22, TH1, and Tc17 cells release cytokines (IL-17, IL-22, and IFN-γ) that drive keratinocyte hyperproliferation, angiogenesis, and sustained immune infiltration. This pathogenic cascade underscores the rationale for targeted therapies, including IL-17, IL-23, and TNF inhibitors. IL, interleukin; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; IFN, interferon; KC, keratinocyte; LC, Langerhans cell; DC, dendritic cell; AMPs, antimicrobial peptides; TLR, Toll-like receptor; NETs, neutrophil extracellular traps; MMP9, matrix metalloproteinase-9; γδT cell, gamma delta T cell; Th, T helper; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index.

Sieminska I, Pieniawska M, Grzywa TM. The immunology of psoriasis—current concepts in pathogenesis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2024;66(2):164-191. doi: 10.1007/s12016-024-08991-7.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Psoriasis Dermpath. The image shows fully developed plaques with parakeratosis, loss of the granular layer, elongated and clubbed rete ridges, suprapapillary epidermal thinning, dilated papillary dermal vessels, and mixed inflammatory infiltrates with Munro microabscesses.

Contributed by N Sathe, MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Majewski M, Konopelski P, Rudnicka L. The influence of genetic factors on the clinical manifestations and response to systemic treatment of plaque psoriasis. Archives of dermatological research. 2025 Mar 17:317(1):582. doi: 10.1007/s00403-025-04132-y. Epub 2025 Mar 17 [PubMed PMID: 40095058]

To SY, Lee CH, Chen YH, Hsu CL, Yang HW, Jiang YS, Wen YL, Chen IW, Kao LT. Psoriasis Risk With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. JAMA dermatology. 2025 Jan 1:161(1):31-38. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2024.4129. Epub [PubMed PMID: 39504056]

Armstrong AW, Mehta MD, Schupp CW, Gondo GC, Bell SJ, Griffiths CEM. Psoriasis Prevalence in Adults in the United States. JAMA dermatology. 2021 Aug 1:157(8):940-946. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.2007. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34190957]

Parisi R,Iskandar IYK,Kontopantelis E,Augustin M,Griffiths CEM,Ashcroft DM,Global Psoriasis Atlas, National, regional, and worldwide epidemiology of psoriasis: systematic analysis and modelling study. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2020 May 28; [PubMed PMID: 32467098]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSieminska I, Pieniawska M, Grzywa TM. The Immunology of Psoriasis-Current Concepts in Pathogenesis. Clinical reviews in allergy & immunology. 2024 Apr:66(2):164-191. doi: 10.1007/s12016-024-08991-7. Epub 2024 Apr 20 [PubMed PMID: 38642273]

Yamanaka K, Yamamoto O, Honda T. Pathophysiology of psoriasis: A review. The Journal of dermatology. 2021 Jun:48(6):722-731. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.15913. Epub 2021 Apr 22 [PubMed PMID: 33886133]

Menter A, Gelfand JM, Connor C, Armstrong AW, Cordoro KM, Davis DMR, Elewski BE, Gordon KB, Gottlieb AB, Kaplan DH, Kavanaugh A, Kiselica M, Kivelevitch D, Korman NJ, Kroshinsky D, Lebwohl M, Leonardi CL, Lichten J, Lim HW, Mehta NN, Paller AS, Parra SL, Pathy AL, Prater EF, Rahimi RS, Rupani RN, Siegel M, Stoff B, Strober BE, Tapper EB, Wong EB, Wu JJ, Hariharan V, Elmets CA. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis with systemic nonbiologic therapies. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2020 Jun:82(6):1445-1486. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.044. Epub 2020 Feb 28 [PubMed PMID: 32119894]

Manchanda Y, De A, Das S, Chakraborty D. Disease Assessment in Psoriasis. Indian journal of dermatology. 2023 May-Jun:68(3):278-281. doi: 10.4103/ijd.ijd_420_23. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37529444]

Elmets CA, Korman NJ, Prater EF, Wong EB, Rupani RN, Kivelevitch D, Armstrong AW, Connor C, Cordoro KM, Davis DMR, Elewski BE, Gelfand JM, Gordon KB, Gottlieb AB, Kaplan DH, Kavanaugh A, Kiselica M, Kroshinsky D, Lebwohl M, Leonardi CL, Lichten J, Lim HW, Mehta NN, Paller AS, Parra SL, Pathy AL, Siegel M, Stoff B, Strober B, Wu JJ, Hariharan V, Menter A. Joint AAD-NPF Guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapy and alternative medicine modalities for psoriasis severity measures. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2021 Feb:84(2):432-470. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.087. Epub 2020 Jul 30 [PubMed PMID: 32738429]

Smith P, Kranyak A, Johnson CE, Haran K, Muraguri Snr I, Maurer T, Bhutani T, Liao W, Kiprono S. Adapting the Goeckerman Regimen for Psoriasis Treatment in Kenya: A Case Study of Successful Management in a Resource-Limited Setting. Psoriasis (Auckland, N.Z.). 2024:14():93-100. doi: 10.2147/PTT.S481148. Epub 2024 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 39224150]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSmith CH, Yiu ZZN, Bale T, Burden AD, Coates LC, Eckert E, Longley N, Mahil SK, McGuire A, Murphy R, Nelson-Piercy C, Owen CM, Parslew R, Woolf RT, Mansour Kiaee Z, Constantin AM, Ezejimofor MC, Exton LS, Mohd Mustapa MF. British Association of Dermatologists guidelines for biologic therapy for psoriasis 2023: a pragmatic update. The British journal of dermatology. 2024 Jan 23:190(2):270-272. doi: 10.1093/bjd/ljad347. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37740557]

Zhang M, Hong S, Wang Q, Sun X, Zhou Y, Luo Y, Liu L, Wang J, Wang C, Lin N, Yan J, Li X. Biopharmaceutical Switching in Psoriasis Treatment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA dermatology. 2025 Aug 6:():. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2025.2714. Epub 2025 Aug 6 [PubMed PMID: 40768223]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKruczek W, Frątczak A, Litwińska-Inglot I, Polak K, Pawlus Z, Rutecka P, Bergler-Czop B, Miziołek B. Comparative Analysis of the Long-Term Real-World Efficacy of Interleukin-17 Inhibitors in a Cohort of Patients with Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis Treated in Poland. Journal of clinical medicine. 2025 Aug 1:14(15):. doi: 10.3390/jcm14155421. Epub 2025 Aug 1 [PubMed PMID: 40807042]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceD'Arino A, Fargnoli MC, Frascione P, Assorgi C, Dattola A, Lora V, Megna M, Pigliacelli F, Vagnozzi E, Orsini D. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab in patients with erythrodermic and sub-erythrodermic psoriasis: a case series. Dermatology reports. 2025 Jul 30:():. doi: 10.4081/dr.2025.10379. Epub 2025 Jul 30 [PubMed PMID: 40823859]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAltamirano De La Cruz AG, Lugo Rincón-Gallardo FJ, Salazar López MD, Ruedas Rodriguez CJ, Mendoza Gómez JM. Arthritis Mutilans: A Devastating Manifestation of Psoriatic Disease Without Dactylitis in a 61-Year-Old Patient. Cureus. 2025 Jul:17(7):e88502. doi: 10.7759/cureus.88502. Epub 2025 Jul 22 [PubMed PMID: 40851710]

Prussick R, Prussick L, Nussbaum D. Nonalcoholic Fatty liver disease and psoriasis: what a dermatologist needs to know. The Journal of clinical and aesthetic dermatology. 2015 Mar:8(3):43-5 [PubMed PMID: 25852814]

Almutairi AG, Aloraini LI, Almutairi RR, Alfaqih AA, Alruwaili SA, Aljefri S. Ocular Manifestations of Psoriasis: A Systematic Review. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2025 Jul:33(5):827-835. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2025.2459710. Epub 2025 Feb 17 [PubMed PMID: 39960409]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAbdel-Azim AA, Ismail RM, Ahmed Elshabasy HS, Pessar DAH. Psychiatric disorders in psoriatic patients: a cross-sectional study in multi-government hospitals. Archives of dermatological research. 2025 Apr 19:317(1):722. doi: 10.1007/s00403-025-04181-3. Epub 2025 Apr 19 [PubMed PMID: 40252117]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSurapaneni D, Dasi SC, Sam N, M J. Methotrexate Toxicity-Induced Pancytopenia and Mucocutaneous Ulcerations in Psoriasis. Cureus. 2024 Aug:16(8):e66222. doi: 10.7759/cureus.66222. Epub 2024 Aug 5 [PubMed PMID: 39238709]

James WA, Rosenberg AL, Wu JJ, Hsu S, Armstrong A, Wallace EB, Lee LW, Merola J, Schwartzman S, Gladman D, Liu C, Koo J, Hawkes JE, Reddy S, Prussick R, Yamauchi P, Lewitt M, Soung J, Weinberg J, Lebwohl M, Glick B, Kircik L, Desai S, Feldman SR, Zaino ML. Full Guidelines-From the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: Perioperative management of systemic immunomodulatory agents in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2024 Aug:91(2):251.e1-251.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2024.03.008. Epub 2024 Mar 17 [PubMed PMID: 38499181]