Introduction

Pneumothorax refers to the presence of air or gas within the pleural space—the space between the visceral and parietal pleura of the thoracic cavity. This accumulation can disrupt normal lung expansion, impairing ventilation and oxygenation. The clinical presentations of pneumothorax range from asymptomatic to a life-threatening emergency, depending on factors such as the volume of air, the rate of accumulation, and the patient's underlying respiratory status.[1][2]

Pneumothorax is categorized into 3 broad types based on its etiology and pathophysiology—spontaneous, traumatic, and tension. Spontaneous pneumothorax occurs without an apparent external cause and is further divided into primary and secondary types. Primary spontaneous pneumothorax develops in individuals without underlying lung disease, most commonly in young, tall, thin males with subclinical pleural blebs. In contrast, secondary spontaneous pneumothorax occurs in patients with preexisting lung conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cystic fibrosis, or pulmonary fibrosis.

Traumatic pneumothorax occurs due to blunt or penetrating chest trauma, including rib fractures, gunshot wounds, or iatrogenic causes, such as lung biopsy, central venous catheter placement, or mechanical ventilation. Tension pneumothorax is a rapidly progressive and potentially fatal condition in which trapped air accumulates under pressure, leading to severe respiratory distress, mediastinal shift, and hemodynamic instability. Immediate needle thoracostomy is required for decompression, followed by definitive chest tube placement.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Traditionally, pneumothorax is divided into primary or secondary based on its etiology. Primary spontaneous pneumothorax is more common in men and is frequently associated with underlying lung disease and smoking.[3] However, this simplified classification has become less accurate, as advancements in diagnostic techniques have revealed that many cases previously classified as primary are associated with secondary causes, such as parenchyma disorders, emphysema, or smoking-related lung disease.[4]

Studies conducted in the United Kingdom have identified COPD as the leading cause of secondary spontaneous pneumothorax, accounting for 70% to 80% of all cases. Tobacco smoking is recognized as the primary risk factor for primary spontaneous pneumothorax, as it increases the likelihood of pneumothorax due to its harmful effects on lung parenchyma.[5]

In addition to traditional tobacco use, emerging evidence suggests that other forms of smoking, including cannabis use and vaping, may also contribute to the development of spontaneous pneumothorax.[6][7] In addition to smoke-related risks, secondary pneumothorax can also result from lung malignancies, infections—such as Pneumocystis jirovecii—and, more recently, severe cases of COVID-19.[8][9]

Pneumothorax is broadly classified into 3 broad categories based on its etiology:

- Traumatic pneumothorax: Results from blunt or penetrating chest trauma, such as rib fractures and gunshot wounds.

- Iatrogenic pneumothorax: A subtype of traumatic pneumothorax caused by medical interventions, such as central line insertion, thoracentesis, device implantation, computed tomography (CT)-guided biopsy, endotracheal intubation, and mechanical ventilation or resuscitation.[10][11][12][13]

- Spontaneous pneumothorax: Occurs without external trauma and is divided into 2 categories.

- Primary spontaneous pneumothorax: Develops in individuals without underlying lung disease

- Secondary spontaneous pneumothorax: Occurs in individuals with significant underlying parenchymal lung disease, such as COPD or cystic fibrosis), often triggered by events such as bleb rupture.[14]

Pneumothorax can also be classified into 4 categories based on its physiological impact:

- Simple pneumothorax

- No communication with the outside atmosphere

- No mediastinal or diaphragmatic shift

- Example: A pleural laceration from a fractured rib [15]

- Communicating pneumothorax

- Occurs when a defect in the chest wall creates an open connection between the pleura space and the external environment, such as a gunshot wound

- Results in paradoxical lung collapse and severe ventilatory impairment [16]

- Tension pneumothorax

- Progressive air accumulation in the pleural cavity leads to:

- Mediastinal shift to the opposite side

- Compression of the vena cava and great vessels, reducing diastolic filling

- Compromised cardiac output, leading to hemodynamic instability

- Occurs when a one-way valve effect traps air in the pleural space, preventing its escape.

- Progressive air accumulation in the pleural cavity leads to:

- Catamenial pneumothorax

- A rare, nontraumatic pneumothorax that occurs in women of childbearing age, typically within 3 to 4 days after menstruation onset

- Often affects the right lung.

- Believed to be caused by pleural endometriosis, although the exact mechanism remains unclear.

Other causes of pneumothorax include barotrauma, occurring from scuba diving or air travel, especially in individuals with preexisting lung disease.[17] In addition, individuals with underlying lung cysts or bullae are at an increased risk of developing pneumothorax in response to rapid pressure changes.

Epidemiology

The incidence of nontraumatic pneumothorax ranges from 7.4 to 18 cases per 100,000 people annually.[18] However, the risk is significantly higher among smokers, with a lifetime risk of 12% compared to 0.1% in nonsmokers.[19]

Primary spontaneous pneumothorax most commonly affects tall, thin-built young males, particularly those who smoke.[20] The condition has a high recurrence rate, with 20% to 60% of patients experiencing a recurrence within the first 3 years following their initial episode.

Secondary spontaneous pneumothorax occurs in individuals with underlying lung disease, resulting in significant variation in its epidemiology. Among patients with COPD, secondary spontaneous pneumothorax accounts for 50% to 70% of cases.[21] In 11% of secondary spontaneous pneumothorax instances, bacterial pneumonia was identified as the causative factor. In addition, pneumothorax is a known complication in 5% to 10% of pneumocystis pneumonia cases, further emphasizing the role of infections in its development.[22]

History and Physical

The clinical presentation of pneumothorax varies depending on its size and etiology. Some patients may be asymptomatic, and the condition may be diagnosed incidentally during the imaging performed for an unrelated reason.[23]

The most common symptoms include chest pain and shortness of breath, reported in 64% to 85% of cases.[24] Chest pain is typically sudden, unilateral (though rarely bilateral), sharp or stabbing, pleuritic, and may radiate to the ipsilateral shoulder or arm. The severity of symptoms varies, depending on the extent of the lung collapse. In cases of primary spontaneous pneumothorax, symptoms may gradually improve after 24 hours, possibly due to the spontaneous reabsorption of air from the pleural space. Other possible symptoms include anxiety and cough, though these are less common.

Physical examination findings depend on the size of the pneumothorax. In small pneumothoraces, the exam may be entirely normal. However, the affected side may have absent breath sounds in larger pneumothoraces. Many patients experiencing a first-time spontaneous pneumothorax may delay seeking medical attention for several days. Hypoxia (oxygen saturation below 90%) is rare, occurring in only 3% to 11% of cases.[25]

Tension Pneumothorax

Tension pneumothorax is a life-threatening emergency that requires immediate recognition and intervention.[26] In addition to chest pain and shortness of breath, patients with tension pneumothorax exhibit hemodynamic compromise, which can include profound hypoxia and hypotension.

The pathophysiology of tension pneumothorax involves the gradual accumulation of air in the pleural space caused by a one-valve effect that prevents air from escaping. The increasing intrapleural pressure leads to a mediastinal shift to the contralateral side, compression of the vena cava, and decreased cardiac output, ultimately resulting in severe hypotension and hypoxia.

On physical examination, classic findings of tension pneumothorax include absent breath sounds on the affected hemithorax, tracheal deviation to the contralateral side, tachycardia, and jugular venous distention. If left untreated, tension pneumothorax rapidly leads to hemodynamic collapse and death.

Patients on mechanical ventilation who develop pneumothorax due to barotrauma experience a sudden increase in intrathoracic pressure and hemodynamic instability, often presenting more abruptly compared to those breathing spontaneously.[27] Early recognition is critical in these cases, as symptoms may rapidly progress to cardiorespiratory failure.

Evaluation

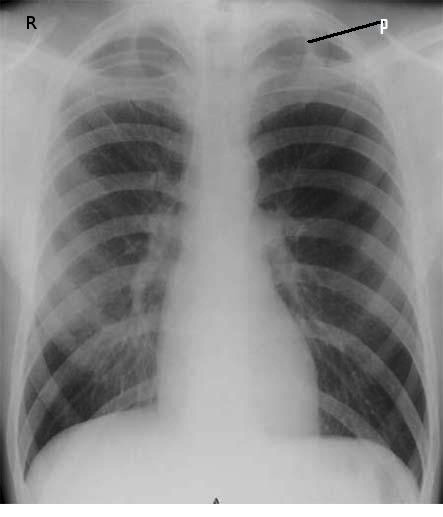

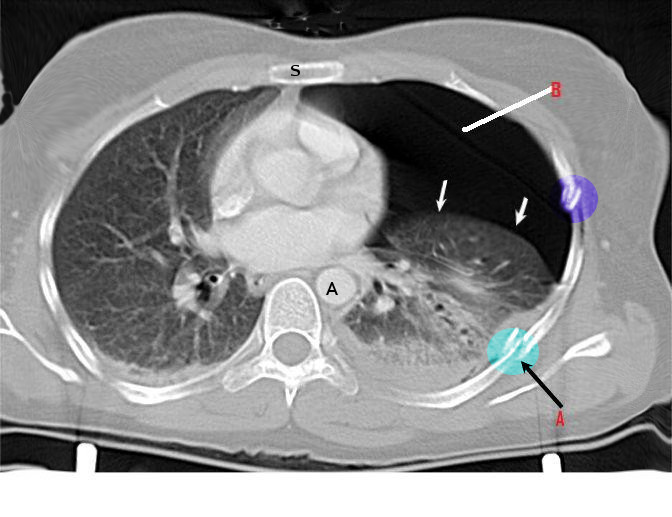

The diagnosis of pneumothorax is based on a combination of patient history, physical examination, laboratory tests, and imaging studies, with chest x-rays being the primary imaging modality (see Image. Primary Spontaneous Pneumothorax). However, small pneumothoraces are often missed on physical examination and chest x-rays and may be detected incidentally on CT scans performed for other indications (see Image. Rib Fracture).[1][28] In cases of moderate-to-severe pneumothorax, arterial blood gas analysis may reveal hypoxia and, in patients with underlying COPD, occasional hypercapnia.[29]

Spontaneous pneumothorax should always be considered when diagnosing patients with sudden-onset pleuritic chest pain and shortness of breath.[14] Similarly, traumatic pneumothorax must be suspected in any case of blunt or penetrating chest trauma.

The diagnostic approach varies depending on the clinical scenario. An upright chest radiograph is typically the preferred initial imaging study. However, tension pneumothorax is a clinical diagnosis, as waiting for imaging can delay life-saving treatment.

Point-of-care ultrasound is increasingly used to evaluate pneumothorax. This modality offers greater accuracy compared to chest x-rays while avoiding radiation exposure.[30] Ultrasound is particularly valuable in critically ill patients and situations requiring rapid bedside assessment.

Classification Based on Size

The distinction between small and large pneumothoraces is based on the distance between the lung margin and the chest wall on imaging: [31]

- Small pneumothorax: Visible rim less than 2 cm between the lung margin and the chest wall.

- Large pneumothorax: Visible rim greater than 2 cm between the lung margin and the chest wall.

Chest x-rays underestimate the size of pneumothorax and may also reveal other findings, such as hydropneumothorax (air and fluid levels in the pleural space), particularly when obtained in the upright position.[32] In cases where clinical suspicion remains high despite a negative chest x-ray, a CT scan can provide a more accurate assessment of pneumothorax size and detect subtle or loculated air collections that may not be visible on standard radiographs.

Bilateral pneumothorax, sometimes called buffalo chest, can be either congenital or iatrogenic. The iatrogenic form typically occurs as a result of thoracic surgical procedures that compromise the anterior connection between the chest cavities. This condition is commonly observed in patients who have undergone lung or heart transplantation, esophagectomy, or lung cryobiopsy.[33][34][35]

Treatment / Management

The management of pneumothorax is guided by its etiology, clinical presentation, and risk stratification.[14][28] The key treatment principles include eliminating air from the pleural space, reducing air leakage, promoting pleural healing, facilitating lung reexpansion, and preventing recurrence.[36]

Asymptomatic Patients

Asymptomatic Patients with an incidentally discovered pneumothorax may not require intervention unless they are at high risk of recurrence. Typically, this decision is not made in the emergency department; instead, these patients should be referred to a pulmonologist for further evaluation and care.

Symptomatic Patients

For symptomatic patients with stable vital signs, initial management may include needle aspiration or small-bore catheter insertion (pigtail catheter) in the emergency department. Evidence suggests that needle aspiration is as safe and effective as tube thoracostomy in cases of primary spontaneous pneumothorax.[37] A recent randomized clinical trial involving unilateral, moderate-to-large primary spontaneous pneumothorax revealed that conservative observation was not inferior to interventional management, with a lower risk of serious adverse events compared to invasive techniques.[38] These patients may require hospital admission for observation. Although oxygen therapy with serial chest radiographs is sometimes used, there are limited supporting data.[39] Importantly, positive pressure-generating therapies, such as noninvasive ventilation or high nasal flow nasal cannula, should not be used due to the risk of air leaks and worsening pneumothorax.[40]

For secondary secondary spontaneous pneumothorax, observation or needle aspiration is typically insufficient. These cases require hospital admission and chest tube insertion (ranging from 20 to 28 French), which is typically connected to a water-seal device with or without additional suctioning.[41](B3)

Management of Unstable Patients

Patients with traumatic or tension pneumothorax require emergent thoracostomy or chest tube placement.[42] In most cases, non-tension pneumothorax can be effectively managed with small-bore pigtail catheters inserted using the Seldinger technique. Very large pneumothoraces may necessitate large-bore chest tubes.[43] A thoracostomy with a large-bore chest tube insertion is necessary if there is a concomitant hemothorax.

Studies have shown that simple aspiration has a higher failure rate compared to chest tube drainage when used as the initial management strategy for complete primary spontaneous pneumothorax cases.[44] As a result, chest tube placement is often preferred in patients with large or recurrent pneumothoraces to ensure adequate lung reexpansion and reduce the risk of early recurrence.(A1)

Air Drainage Techniques

Air drainage techniques are essential in managing pneumothorax. These techniques help remove air from the pleural space, facilitate lung reexpansion, and prevent recurrence. The choice of technique depends on the size of the pneumothorax, the patient's clinical stability, and the underlying etiology.

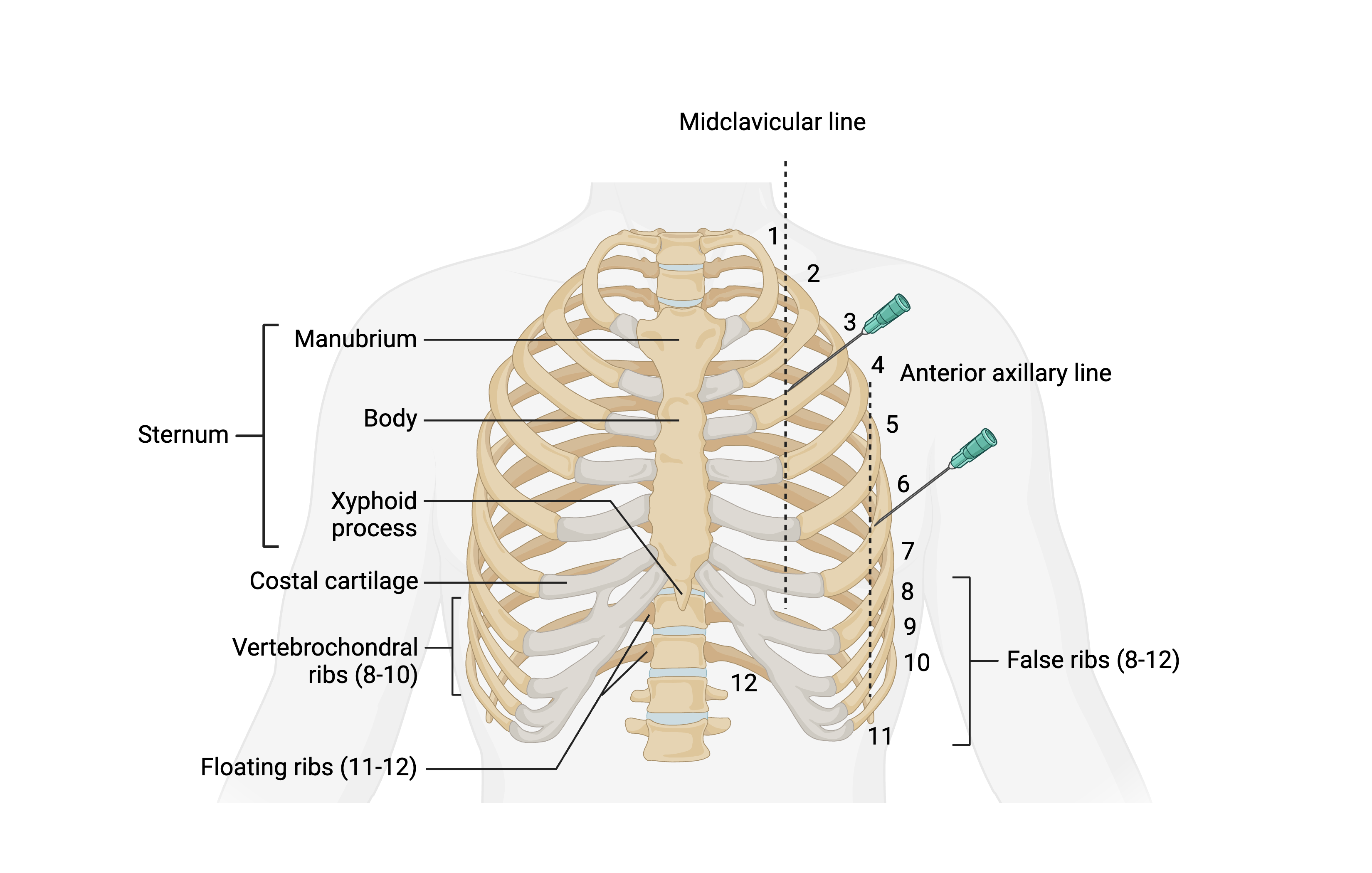

- Needle aspiration technique: A large-bore (14-gauge) needle approximately 10 cm long can be inserted at one of 2 locations (see Image. Chest Wall Decompression.)

- Second intercostal space at the midclavicular line, above the superior edge of the third rib

- Fifth intercostal space at the anterior axillary line, above the upper border of the sixth rib

This placement method aims to prevent injury to the neurovascular bundle, which runs along the inferior edge of each rib.[45]

- Large-bore catheter drainage technique: For cases requiring large-bore catheter drainage, an 8.3-French pigtail catheter can be introduced into the pleural cavity using ultrasound. Similar to needle aspiration, there are multiple insertion points.

- Second intercostal space at the midclavicular line

- Fifth intercostal space at the anterior axillary line, ensuring placement above the superior rib edge to minimize the risk of neurovascular bundle injury.[46]

(A1)

Special Considerations in Pneumothorax Management

The management of pneumothorax in special populations requires specific considerations. In pregnant women, nearly 50% of pneumothorax cases resolve with conservative observation, and fetal complications remain below 5%.[47] Patients with lymphangioleiomyomatosis, even if asymptomatic, should be educated about the risk of pneumothorax, particularly during pregnancy, and should seek immediate medical attention if symptoms arise. Throughout pregnancy, patients with lymphangioleiomyomatosis should be co-managed by a pulmonologist and an obstetrician with expertise.[48](A1)

For patients with primary spontaneous pneumothorax who have a high risk of recurrence, 2 surgical approaches have demonstrated comparable effectiveness:

- Thoracic pleurodesis using pleural abrasion with minocycline pleurodesis

- Apical pleurectomy

Both techniques effectively prevent recurrence and are viable management options for high-risk individuals.[49](A1)

Pharmacological Management and Pain Control

Pharmacotherapy for pneumothorax primarily focuses on pain control, both from the pneumothorax itself and procedures such as thoracostomy or needle aspiration. Pain control can be achieved through: [50]

- Local anesthetic infiltration at the thoracostomy site

- Intravenous or oral pain medications

- Regional anesthesia techniques, such as intercostal nerve blocks

For patients undergoing video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for pneumothorax, intercostal nerve blocks are as effective as thoracic epidural analgesia in managing postoperative pain, with the added benefit of improved patient mobility.[50] In addition, intercostal nerve blocks are associated with fewer systemic adverse effects, such as hypotension and urinary retention, making them a safer and more convenient option for pain management in these patients.

During chest tube insertion, prophylactic antibiotics should be considered to prevent insertion site infections and to reduce the risk of complications, such as empyema. These antibiotics can also be used for patients requiring prolonged chest tube placement.

Differential Diagnosis

Nontraumatic spontaneous pneumothorax can present with symptoms similar to various pulmonary, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, and psychiatric conditions. The following differential diagnosis should be considered:

- Pulmonary

- Pneumonia

- Acute asthma exacerbation

- Bronchitis

- Pulmonary embolism

- Tuberculosis

- Pulmonary empyema

- Lung abscess

- Cardiovascular

- Aortic dissection

- Acute coronary syndrome

- Myocarditis

- Pericarditis

- Pleurodynia

- Musculoskeletal and Gastrointestinal

- Costochondritis

- Diaphragmatic injuries

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- Esophageal spasm

- Mallory-Weiss tear

- Boerhaave syndrome

- Mediastinitis

- Psychiatric

- Anxiety or panic attack

The possibility of tension pneumothorax and concomitant hemothorax must always be considered in traumatic pneumothorax. Patients with traumatic pneumothorax often have a high association with additional thoracic and abdominal injuries. Therefore, a comprehensive trauma evaluation by emergency physicians and trauma surgeons is essential to identify and manage any concurrent injuries effectively.

Prognosis

The prognosis of spontaneous pneumothorax largely depends on the size of the pneumothorax, the underlying cause, and the patient's overall health. In many cases, small, primary spontaneous pneumothoraxes may resolve on their own with minimal intervention, and the prognosis is generally good. However, recurrence rates are high, ranging from 20% to 60% within 3 years of the initial episode.[51]

For patients with secondary spontaneous pneumothorax, often related to underlying lung diseases, the prognosis can be more guarded and may require more aggressive treatment. Early detection and appropriate management are key to reducing complications and improving long-term outcomes.

Complications

Misdiagnosis is a common complication of pneumothorax. Several factors can contribute, including an incomplete or inadequate history or physical examination, low clinical suspicion, failure to obtain a chest radiograph, or failure to recognize a pneumothorax on imaging. Misdiagnosis can result in delayed treatment, leading to serious consequences, such as: [36][52][53][54][55]

- Conversion to tension pneumothorax

- Hypoxemic respiratory failure

- Shock

- Respiratory or cardiac arrest

- Empyema

- Reexpansion pulmonary edema

- Iatrogenic complications from needle decompression or thoracostomy procedure, including lung to re-expand, lung laceration, infection at the insertion site, pleural space infection, intercostal vessel or internal mammary artery laceration, hemothorax, persistent air leak, and damage to the intercostal neurovascular bundle

- Chest tube-induced arrhythmia

- Pneumomediastinum, where air from the pneumothorax tracks into the mediastinum, may present as air lucency around the heart on a chest x-ray. A characteristic crunching sound, Hamman's crunch, can also be auscultated during the cardiac examination, most notably in the left lateral decubitus position.

Consultations

The management of pneumothorax often requires consultation with multiple specialists, depending on its severity and underlying cause. In cases of uncomplicated primary spontaneous pneumothorax, a pulmonologist or emergency medicine physician may oversee treatment, including observation, oxygen therapy, or simple aspiration. However, if the pneumothorax is large, recurrent, or associated with significant symptoms, a thoracic surgeon may be consulted for chest tube placement, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery, or pleurodesis to prevent recurrence.

Secondary spontaneous pneumothorax, often linked to underlying lung disease such as COPD or interstitial lung disease, requires consultation with a pulmonologist to optimize management and prevent future episodes. If the patient requires ventilatory support or intensive care monitoring, anesthesiologists and critical care specialists may also be involved. In addition, in cases of iatrogenic pneumothorax resulting from medical procedures, collaboration with the primary treating specialist, such as an interventional radiologist or proceduralist, may be necessary to guide further management and prevent complications.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Preventing recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax requires patient education on risk factors and lifestyle modifications. Patients should be advised to avoid smoking, as it significantly increases the risk of recurrence. Activities involving significant pressure changes, such as scuba diving, high-altitude travel, and flying in unpressurized aircraft, should be cautiously approached, particularly in individuals with a history of pneumothorax.

Patients with recurrent pneumothorax or underlying lung disease should be educated on recognizing early symptoms, such as sudden chest pain or shortness of breath, and should seek prompt medical attention. Patients who have undergone surgical interventions such as pleurodesis should be counseled on postoperative care and the potential for residual lung function changes. Long-term follow-up with a pulmonologist may be recommended to monitor lung health and prevent complications.

Pearls and Other Issues

Key considerations to keep in mind about acute pneumothorax include the following:

- Pneumothorax is the presence of air in the pleural space, leading to lung collapse.

- Symptoms include sudden-onset pleuritic chest pain and dyspnea.

- Tension pneumothorax may present with hypotension, tachycardia, jugular venous distention, tracheal deviation away from the affected side, and respiratory distress.

- Physical examination findings include decreased breath sounds on the affected side, hyperresonance to percussion, decreased tactile fremitus, distended neck veins, and hypotension.

- Chest x-ray shows a visceral pleural line without lung markings beyond it.

- Small stable pneumothorax (<2 cm, minimal symptoms) can be observed with oxygen therapy.

- Large or symptomatic pneumothorax (>2 cm) can be treated with needle aspiration or chest tube placement.

- Tension pneumothorax is a medical emergency and should be treated with immediate needle decompression followed by chest tube placement.

- Recurrent cases may require pleurodesis or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery.

- Prevention includes avoiding smoking, high-altitude travel, diving, or unpressurized flights.

- Follow-up imaging should be obtained to ensure resolution.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Pneumothorax is a common condition, with over 5 million intensive care unit admissions in the United States annually. Managing this condition requires a coordinated interprofessional team, including emergency department physicians, general surgeons, thoracic surgeons, critical care specialists, radiologists, and specialty-trained emergency or critical care nurses. Nurses play a crucial role in patient monitoring after chest tube placement, ensuring proper wound care, assessing breath sounds, and maintaining the patency of the drainage system. Any abnormalities must be promptly reported to the team.

Early recognition of tension pneumothorax by nurses is crucial, as it can rapidly lead to deterioration in a patient's condition. As frontline providers, they must be prepared to notify the clinical team immediately and assist in emergency interventions.

Although chest x-ray remains the standard diagnostic tool, advancements in radiology software have improved detection, particularly for less experienced practitioners.[56] Effective management relies on a well-trained, interprofessional team with clear and rapid communication, ultimately leading to better patient outcomes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Chest Wall Decompression. An illustration of techniques to acutely decompress tension pneumothorax using a 14-gauge needle inserted either in the 2nd intercostal space at the top edge of the third on at the midclavicular line or at the 5th intercostal space at the top edge of 6th rib at the anterior axillary line.

Created in BioRender. Bohlen, J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/d53u966

References

Swierzy M, Helmig M, Ismail M, Rückert J, Walles T, Neudecker J. [Pneumothorax]. Zentralblatt fur Chirurgie. 2014 Sep:139 Suppl 1():S69-86; quiz S87. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1383029. Epub 2014 Sep 29 [PubMed PMID: 25264729]

Papagiannis A, Lazaridis G, Zarogoulidis K, Papaiwannou A, Karavergou A, Lampaki S, Baka S, Mpoukovinas I, Karavasilis V, Kioumis I, Pitsiou G, Katsikogiannis N, Tsakiridis K, Rapti A, Trakada G, Karapantzos I, Karapantzou C, Zissimopoulos A, Zarogoulidis P. Pneumothorax: an up to date "introduction". Annals of translational medicine. 2015 Mar:3(4):53. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.03.23. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25861608]

Bense L, Lewander R, Eklund G, Hedenstierna G, Wiman LG. Nonsmoking, non-alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency-induced emphysema in nonsmokers with healed spontaneous pneumothorax, identified by computed tomography of the lungs. Chest. 1993 Feb:103(2):433-8 [PubMed PMID: 8432133]

Bintcliffe OJ, Hallifax RJ, Edey A, Feller-Kopman D, Lee YC, Marquette CH, Tschopp JM, West D, Rahman NM, Maskell NA. Spontaneous pneumothorax: time to rethink management? The Lancet. Respiratory medicine. 2015 Jul:3(7):578-88. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00220-9. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26170077]

Bense L,Eklund G,Wiman LG, Smoking and the increased risk of contracting spontaneous pneumothorax. Chest. 1987 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 3677805]

Hedevang Olesen W, Katballe N, Sindby JE, Titlestad IL, Andersen PE, Ekholm O, Lindahl-Jacobsen R, Licht PB. Cannabis increased the risk of primary spontaneous pneumothorax in tobacco smokers: a case-control study. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2017 Oct 1:52(4):679-685. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezx160. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28605480]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAberegg SK, Cirulis MM, Maddock SD, Freeman A, Keenan LM, Pirozzi CS, Raman SM, Schroeder J, Mann H, Callahan SJ. Clinical, Bronchoscopic, and Imaging Findings of e-Cigarette, or Vaping, Product Use-Associated Lung Injury Among Patients Treated at an Academic Medical Center. JAMA network open. 2020 Nov 2:3(11):e2019176. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19176. Epub 2020 Nov 2 [PubMed PMID: 33156346]

Afessa B. Pleural effusions and pneumothoraces in AIDS. Current opinion in pulmonary medicine. 2001 Jul:7(4):202-9 [PubMed PMID: 11470975]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMcGuinness G, Zhan C, Rosenberg N, Azour L, Wickstrom M, Mason DM, Thomas KM, Moore WH. Increased Incidence of Barotrauma in Patients with COVID-19 on Invasive Mechanical Ventilation. Radiology. 2020 Nov:297(2):E252-E262. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020202352. Epub 2020 Jul 2 [PubMed PMID: 32614258]

Lorenz FJ, Goyal N. Iatrogenic Pneumothorax During Hypoglossal Nerve Stimulator Implantation: A Large Database Analysis. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2023 Apr:168(4):876-880. doi: 10.1177/01945998221122696. Epub 2023 Jan 29 [PubMed PMID: 36066978]

Sabatino V, Russo U, D'Amuri F, Bevilacqua A, Pagnini F, Milanese G, Gentili F, Nizzoli R, Tiseo M, Pedrazzi G, De Filippo M. Pneumothorax and pulmonary hemorrhage after CT-guided lung biopsy: incidence, clinical significance and correlation. La Radiologia medica. 2021 Jan:126(1):170-177. doi: 10.1007/s11547-020-01211-0. Epub 2020 May 6 [PubMed PMID: 32377914]

Rowland D, Vryhof N, Overton D, Mastenbrook J. Tension Hemopneumothorax in the Setting of Mechanical CPR during Prehospital Cardiac Arrest. Prehospital emergency care. 2021 Mar-Apr:25(2):274-280. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2020.1743800. Epub 2020 Apr 14 [PubMed PMID: 32208039]

Cantey EP, Walter JM, Corbridge T, Barsuk JH. Complications of thoracentesis: incidence, risk factors, and strategies for prevention. Current opinion in pulmonary medicine. 2016 Jul:22(4):378-85. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000285. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27093476]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBaumann MH. Management of spontaneous pneumothorax. Clinics in chest medicine. 2006 Jun:27(2):369-81 [PubMed PMID: 16716824]

Henry MT. Simple sequential treatment for primary spontaneous pneumothorax: one step closer. The European respiratory journal. 2006 Mar:27(3):448-50 [PubMed PMID: 16507842]

Eguchi T, Hamanaka K, Kobayashi N, Saito G, Shiina T, Kurai M, Yoshida K. Occurrence of a simultaneous bilateral spontaneous pneumothorax due to a pleuro-pleural communication. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2011 Sep:92(3):1124-6. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.03.066. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21871318]

Ioannidis G, Lazaridis G, Baka S, Mpoukovinas I, Karavasilis V, Lampaki S, Kioumis I, Pitsiou G, Papaiwannou A, Karavergou A, Katsikogiannis N, Sarika E, Tsakiridis K, Korantzis I, Zarogoulidis K, Zarogoulidis P. Barotrauma and pneumothorax. Journal of thoracic disease. 2015 Feb:7(Suppl 1):S38-43. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.01.31. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25774306]

McKnight CL, Burns B. Pneumothorax. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28722915]

Larson R. Primary spontaneous pneumothorax presenting to a chiropractic clinic as undifferentiated thoracic spine pain: a case report. The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association. 2016 Mar:60(1):66-72 [PubMed PMID: 27069268]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceComelli I, Bologna A, Ticinesi A, Magnacavallo A, Comelli D, Meschi T, Cervellin G. Incidence of primary spontaneous pneumothorax is not associated with microclimatic variations. Results of a seven-year survey in a temperate climate area. Monaldi archives for chest disease = Archivio Monaldi per le malattie del torace. 2017 May 18:87(1):793. doi: 10.4081/monaldi.2017.793. Epub 2017 May 18 [PubMed PMID: 28635192]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGuo Y, Xie C, Rodriguez RM, Light RW. Factors related to recurrence of spontaneous pneumothorax. Respirology (Carlton, Vic.). 2005 Jun:10(3):378-84 [PubMed PMID: 15955153]

Afessa B. Pleural effusion and pneumothorax in hospitalized patients with HIV infection: the Pulmonary Complications, ICU support, and Prognostic Factors of Hospitalized Patients with HIV (PIP) Study. Chest. 2000 Apr:117(4):1031-7 [PubMed PMID: 10767235]

Sahn SA, Heffner JE. Spontaneous pneumothorax. The New England journal of medicine. 2000 Mar 23:342(12):868-74 [PubMed PMID: 10727592]

Gottlieb M, Long B. Managing Spontaneous Pneumothorax. Annals of emergency medicine. 2023 May:81(5):568-576. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2022.08.447. Epub 2022 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 36328849]

Sousa C, Neves J, Sa N, Goncalves F, Oliveira J, Reis E. Spontaneous pneumothorax: a 5-year experience. Journal of clinical medicine research. 2011 May 19:3(3):111-7. doi: 10.4021/jocmr560w. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21811541]

Roberts DJ, Leigh-Smith S, Faris PD, Blackmore C, Ball CG, Robertson HL, Dixon E, James MT, Kirkpatrick AW, Kortbeek JB, Stelfox HT. Clinical Presentation of Patients With Tension Pneumothorax: A Systematic Review. Annals of surgery. 2015 Jun:261(6):1068-78. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001073. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25563887]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDiaz R, Heller D. Barotrauma and Mechanical Ventilation. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31424810]

Idrees MM, Ingleby AM, Wali SO. Evaluation and management of pneumothorax. Saudi medical journal. 2003 May:24(5):447-52 [PubMed PMID: 12847616]

Light RW, O'Hara VS, Moritz TE, McElhinney AJ, Butz R, Haakenson CM, Read RC, Sassoon CS, Eastridge CE, Berger R. Intrapleural tetracycline for the prevention of recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax. Results of a Department of Veterans Affairs cooperative study. JAMA. 1990 Nov 7:264(17):2224-30 [PubMed PMID: 2214100]

Alrajab S, Youssef AM, Akkus NI, Caldito G. Pleural ultrasonography versus chest radiography for the diagnosis of pneumothorax: review of the literature and meta-analysis. Critical care (London, England). 2013 Sep 23:17(5):R208. doi: 10.1186/cc13016. Epub 2013 Sep 23 [PubMed PMID: 24060427]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMacDuff A, Arnold A, Harvey J, BTS Pleural Disease Guideline Group. Management of spontaneous pneumothorax: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline 2010. Thorax. 2010 Aug:65 Suppl 2():ii18-31. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.136986. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20696690]

Stark P, Leung A. Effects of lobar atelectasis on the distribution of pleural effusion and pneumothorax. Journal of thoracic imaging. 1996 Spring:11(2):145-9 [PubMed PMID: 8820023]

Matsuoka S, Miyazawa M, Kashimoto K, Kobayashi H, Mitsui F, Tsunoda H, Kunitomo K, Chisuwa H, Haba Y. A case of simultaneous bilateral spontaneous pneumothorax after the Nuss procedure. General thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2016 Jun:64(6):347-50. doi: 10.1007/s11748-014-0489-4. Epub 2014 Oct 29 [PubMed PMID: 25352312]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSalman S, Lofino L, Mastinu S, Ammirabile A, Francone M, Politi LS, Lanza E. Buffalo Chest: An Overlooked Risk Factor for Thoracic Interventional Procedures? Cardiovascular and interventional radiology. 2023 May:46(5):697-700. doi: 10.1007/s00270-023-03381-6. Epub 2023 Feb 13 [PubMed PMID: 36781436]

Nishiyama K, Baba T, Oda T, Sekine A, Niwa T, Yamada S, Kaburaki S, Nagasawa R, Okudela K, Takemura T, Iwasawa T, Mineshita M, Ogura T. Bilateral Pneumothorax after a Transbronchial Lung Cryobiopsy for Interstitial Lung Disease. Internal medicine (Tokyo, Japan). 2024 Mar 15:63(6):839-842. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.2149-23. Epub 2023 Aug 2 [PubMed PMID: 37532548]

Huang Y, Huang H, Li Q, Browning RF, Parrish S, Turner JF Jr, Zarogoulidis K, Kougioumtzi I, Dryllis G, Kioumis I, Pitsiou G, Machairiotis N, Katsikogiannis N, Courcoutsakis N, Madesis A, Diplaris K, Karaiskos T, Zarogoulidis P. Approach of the treatment for pneumothorax. Journal of thoracic disease. 2014 Oct:6(Suppl 4):S416-20. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.08.24. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25337397]

Zehtabchi S, Rios CL. Management of emergency department patients with primary spontaneous pneumothorax: needle aspiration or tube thoracostomy? Annals of emergency medicine. 2008 Jan:51(1):91-100, 100.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.06.009. Epub 2007 Sep 29 [PubMed PMID: 18166436]

Brown SGA, Ball EL, Perrin K, Asha SE, Braithwaite I, Egerton-Warburton D, Jones PG, Keijzers G, Kinnear FB, Kwan BCH, Lam KV, Lee YCG, Nowitz M, Read CA, Simpson G, Smith JA, Summers QA, Weatherall M, Beasley R, PSP Investigators. Conservative versus Interventional Treatment for Spontaneous Pneumothorax. The New England journal of medicine. 2020 Jan 30:382(5):405-415. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910775. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31995686]

Northfield TC. Oxygen therapy for spontaneous pneumothorax. British medical journal. 1971 Oct 9:4(5779):86-8 [PubMed PMID: 4938315]

Parke R, McGuinness S, Eccleston M. Nasal high-flow therapy delivers low level positive airway pressure. British journal of anaesthesia. 2009 Dec:103(6):886-90. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep280. Epub 2009 Oct 20 [PubMed PMID: 19846404]

Nava GW, Walker SP. Management of the Secondary Spontaneous Pneumothorax: Current Guidance, Controversies, and Recent Advances. Journal of clinical medicine. 2022 Feb 22:11(5):. doi: 10.3390/jcm11051173. Epub 2022 Feb 22 [PubMed PMID: 35268264]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAnderson D, Chen SA, Godoy LA, Brown LM, Cooke DT. Comprehensive Review of Chest Tube Management: A Review. JAMA surgery. 2022 Mar 1:157(3):269-274. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.7050. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35080596]

Tsai TM, Lin MW, Li YJ, Chang CH, Liao HC, Liu CY, Hsu HH, Chen JS. The Size of Spontaneous Pneumothorax is a Predictor of Unsuccessful Catheter Drainage. Scientific reports. 2017 Mar 15:7(1):181. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00284-8. Epub 2017 Mar 15 [PubMed PMID: 28298628]

Marx T, Joly LM, Parmentier AL, Pretalli JB, Puyraveau M, Meurice JC, Schmidt J, Tiffet O, Ferretti G, Lauque D, Honnart D, Al Freijat F, Dubart AE, Grandpierre RG, Viallon A, Perdu D, Roy PM, El Cadi T, Bronet N, Duncan G, Cardot G, Lestavel P, Mauny F, Desmettre T. Simple Aspiration versus Drainage for Complete Pneumothorax: A Randomized Noninferiority Trial. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2023 Jun 1:207(11):1475-1485. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202110-2409OC. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36693146]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePasquier M, Hugli O, Carron PN. Videos in clinical medicine. Needle aspiration of primary spontaneous pneumothorax. The New England journal of medicine. 2013 May 9:368(19):e24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMvcm1111468. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23656667]

Chang SH, Kang YN, Chiu HY, Chiu YH. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Comparing Pigtail Catheter and Chest Tube as the Initial Treatment for Pneumothorax. Chest. 2018 May:153(5):1201-1212. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.01.048. Epub 2018 Feb 13 [PubMed PMID: 29452099]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAgrafiotis AC, Assouad J, Lardinois I, Markou GA. Pneumothorax and Pregnancy: A Systematic Review of the Current Literature and Proposal of Treatment Recommendations. The Thoracic and cardiovascular surgeon. 2021 Jan:69(1):95-100. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1702160. Epub 2020 Mar 21 [PubMed PMID: 32199405]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceJohnson SR. The ERS guidelines for LAM: trying a rationale approach to a rare disease. Respiratory medicine. 2010 Jul:104 Suppl 1():S33-41. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.03.015. Epub 2010 May 6 [PubMed PMID: 20451364]

Chen JS, Hsu HH, Huang PM, Kuo SW, Lin MW, Chang CC, Lee JM. Thoracoscopic pleurodesis for primary spontaneous pneumothorax with high recurrence risk: a prospective randomized trial. Annals of surgery. 2012 Mar:255(3):440-5. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824723f4. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22323011]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSpaans LN, van Steenwijk QCA, Seiranjan A, Janssen N, de Loos ER, Susa D, Eerenberg JP, Bouwman RAA, Dijkgraaf MG, van den Broek FJC. Pain management after pneumothorax surgery: intercostal nerve block or thoracic epidural analgesia. Interdisciplinary cardiovascular and thoracic surgery. 2023 Nov 2:37(5):. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivad180. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37941433]

Sadikot RT, Greene T, Meadows K, Arnold AG. Recurrence of primary spontaneous pneumothorax. Thorax. 1997 Sep:52(9):805-9 [PubMed PMID: 9371212]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceEggeling S. [Complications in the therapy of spontaneous pneumothorax]. Der Chirurg; Zeitschrift fur alle Gebiete der operativen Medizen. 2015 May:86(5):444-52. doi: 10.1007/s00104-014-2866-z. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25995086]

Slade M. Management of pneumothorax and prolonged air leak. Seminars in respiratory and critical care medicine. 2014 Dec:35(6):706-14. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1395502. Epub 2014 Dec 2 [PubMed PMID: 25463161]

Peyrin JC, Charlet JP, Duret J, Crepel N, Brichon PY. [Reexpansion pulmonary edema after pneumothorax. Apropos of a case. Review of the literature]. Journal de chirurgie. 1988 Mar:125(3):199-202 [PubMed PMID: 3286664]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCardozo S, Belgrave K. A shocking complication of a pneumothorax: chest tube-induced arrhythmias and review of the literature. Case reports in cardiology. 2014:2014():681572. doi: 10.1155/2014/681572. Epub 2014 Jul 24 [PubMed PMID: 25147742]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLey-Zaporozhan J, Shoushtari H, Menezes R, Zelovitzky L, Odedra D, Jimenez-Juan L, Brunet K, Karimzad Y, Paul NS. Enhanced pneumothorax visualization in ICU patients using portable chest radiography. PloS one. 2018:13(12):e0209770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0209770. Epub 2018 Dec 21 [PubMed PMID: 30576378]