Introduction

The term "Pott puffy tumor" (PPT) refers to edema of part or all of the forehead due to a subperiosteal abscess associated with frontal bone osteomyelitis (see Image. Example of a Pott Puffy Tumor). While the word "tumor" typically suggests neoplasia, in this context, it refers to swelling as one of Celsus' "4 cardinal signs of inflammation"—the other 3 being calor (heat), rubor (redness), and dolor (pain).

PPT was first described in 1760 by Sir Percivall Pott as a complication of a frontal bone fracture.[1] Sir Percivall Pott was a prominent surgeon of the eighteenth century, known for identifying the link between chimney sweeping and scrotal cancer, as well as for describing mycobacterial infection of the spine (Pott disease) and bimalleolar ankle fractures (Pott fractures). In 1775, Pott documented a more typical case of PPT, which developed as a complication of frontal sinusitis. He also outlined its treatment through operative drainage—a method that remains a mainstay of treatment today.[2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The most common cause of PPT is infection of the frontal or ethmoid sinuses, whether acute or chronic. Sinusitis affects approximately 1 in 8 individuals in the United States and typically resolves without complications. Only 0.5% to 2% of patients develop bacterial sinusitis, and 80% of these cases resolve without antibiotics. However, in rare instances, untreated bacterial sinusitis can lead to severe complications, such as PPT.[3][4][5] Head trauma, particularly frontal bone fractures, is the second most common cause of PPT, which develops due to the direct extension of a wound infection.[6]

Less common causes of PPT, reported in small numbers of cases, include cranial surgery, dental infections, mastoiditis, cocaine abuse, malignancy, insect bites, and acupuncture.[7][8][6][9][10] Risk factors that may increase the likelihood of developing PPT in the context of fronto-ethmoid sinusitis include diabetes mellitus, allergic rhinitis, chronic renal failure, aplastic anemia, and other conditions that cause immunosuppression.[11]

Approximately half of PPT cases involve polymicrobial infections.[7][12][8][4][13][14] The most commonly identified organisms include non-enterococcal streptococci (47%), anaerobic oral bacteria (28%), and staphylococci (22%), with streptococci being the most likely to cause intracranial complications.[7] Less common organisms that have been reported include Fusobacterium necrophorum, Haemophilus influenzae, Enterococcus faecalis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, Pasteurella multocida, Proteus mirabilis, Actinomyces naeslundii, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Bacteroides fragilis.[12][14]

Epidemiology

PPT is a rare clinical condition, and its incidence has significantly decreased with the advent of antibiotics. Although uncommon, rapid recognition and prompt treatment are essential for optimizing patient outcomes. Although PPT can occur across all age groups, it is most commonly seen in individuals between the ages of 6 and 15. This age range coincides with the peak growth and vascularity of the frontal sinuses, which increases the potential for hematogenous spread of infection.[15] Nevertheless, PPT has been reported in individuals aged between 2 and 83. In younger patients, infection may originate from the ethmoid cells before frontal sinus pneumatization is complete, while in older individuals, trauma is a more common cause.[16][8][6][13][17]

Approximately 75% of cases occur in patients aged 30 or below.[2] The male-to-female incidence ratio is 9:1, possibly due to the higher likelihood of respiratory infections in male children and increased risk of cranial trauma in adult males.[2] Immunocompromised individuals face a higher risk of PPT, which is rarely observed in immunocompetent adults.[14][7][8][4][6][13] Adults are more likely to develop PPT due to trauma, whereas children typically have a recent history of an upper respiratory tract infection.[2]

Pathophysiology

The increased prominence of the frontal scalp characteristic of PPT results from the accumulation of a subperiosteal abscess originating from underlying osteomyelitis of the frontal bone. If left untreated, this condition can lead to severe intracranial complications, including epidural empyema, subdural empyema, meningitis, and venous thrombosis.[8][13] The most common mechanism of osteomyelitis development begins with either untreated or inadequately treated frontal sinusitis. Subsequent septic thrombophlebitis causes vascular compromise and bone necrosis.

The communication between the frontal sinus and the dural venous plexus through the valveless diploic veins of Galen can allow septic emboli to spread, leading to intracranial involvement with or without frontal bone erosion.[8][13] Additionally, frontal bone osteomyelitis can arise from the direct extension of an infection following open trauma to the forehead. If the wound is contaminated, bacteria can be introduced directly into the bone through a skull fracture.[11][13]

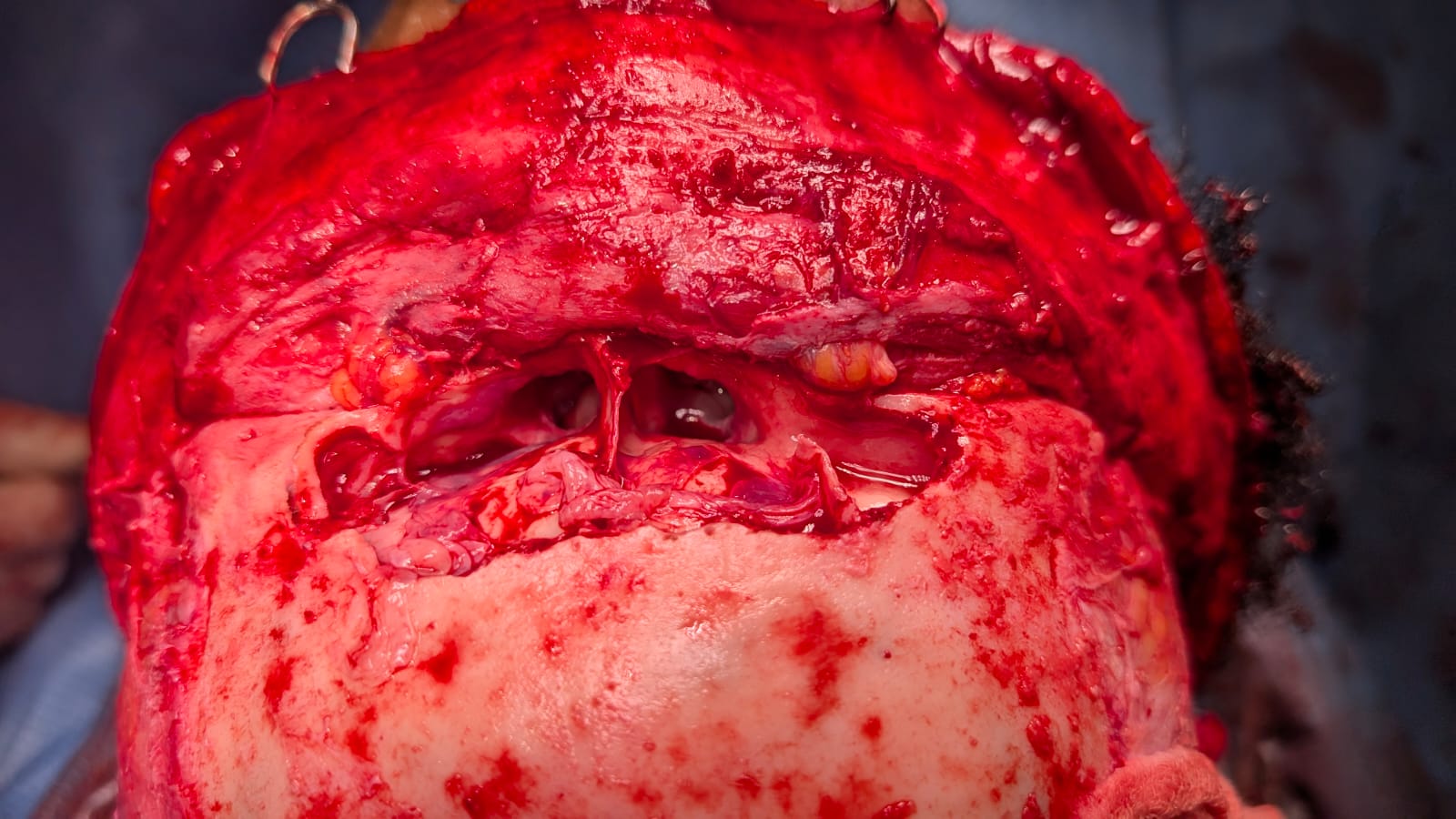

History and Physical

Patients with PPT typically present with fluctuant, tender, "doughy" edema of the frontal scalp, which may be localized or generalized (see Image. Pott Puffy Tumor in a Girl Aged 8 on Day 12 of Infection).[5][13] The most common symptoms include forehead swelling, headache, purulent or non-purulent rhinorrhea, and fever, although fever occurs in fewer than 50% of cases.[12][3][5][14][18] Additional possible signs and symptoms that may present in PPT include glabellar and periorbital swelling, nausea, vomiting, and cutaneous fistulae[8][3]

Increased intracranial pressure should be suspected if patients develop nausea, vomiting, photophobia, cranial nerve deficits, hemiparesis, seizures, altered mental status, lethargy, or obtundation.[12] In the pediatric population, symptoms may be nonspecific and vary depending on the severity of the infection. Some children present with an indolent course, exhibiting only headache and rhinorrhea, with or without fever, making diagnosis dependent on a high index of suspicion.[5]

Evaluation

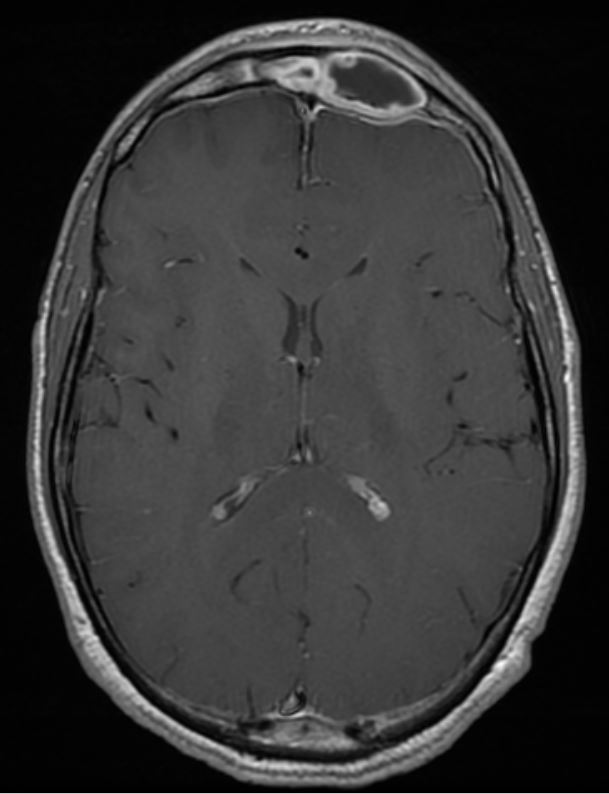

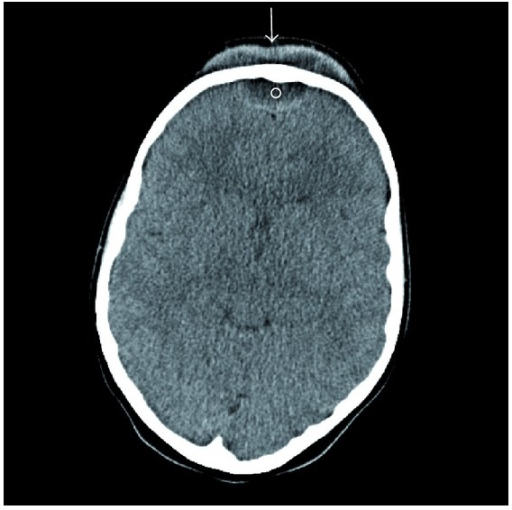

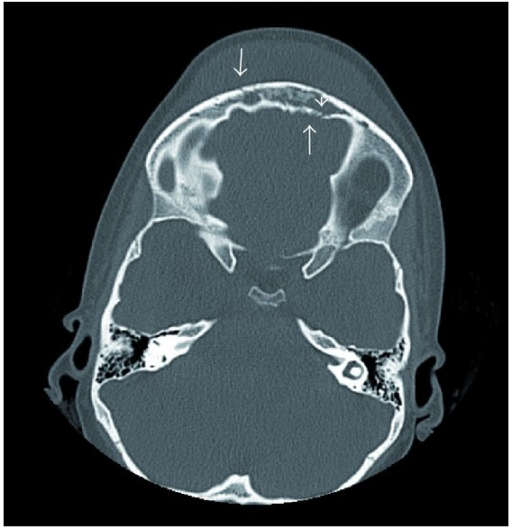

Imaging should be performed as soon as PPT is suspected, as it is crucial in determining prognosis and guiding acute management. The choice between contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) depends on clinical judgment and the specific diagnostic goals. Both CT and MRI can identify PPT, subperiosteal abscesses, and intracranial fluid. However, CT is superior for assessing air-bone interfaces and any frontal bone or skull base involvement, while MRI provides more detailed imaging of soft tissue anomalies (see Images. Pott Puffy Tumor With Frontal Sinusitis and Axial Contrast-Enhanced CT of Pott Puffy Tumor in a Girl Aged 8).[12][8]

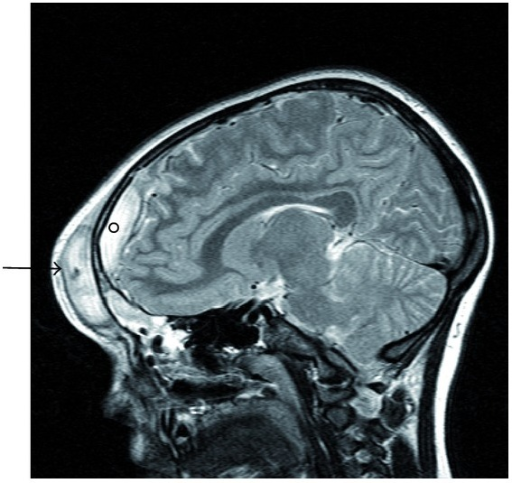

In addition, MRI also offers advantages in better characterizing intracranial infections and dural venous sinus thrombosis compared to CT.[3][5] MRI is the preferred imaging modality for postoperative follow-up, as it avoids radiation exposure. However, obtaining an MRI in some centers in the acute setting can be challenging, potentially delaying diagnosis and treatment (see Image. Sagittal MRI of Pott Puffy Tumor in a Girl Aged 8).[6][11] MRI can also be challenging in pediatric patients due to its prolonged duration and loud noise, which may cause discomfort. In contrast, CT scanning is faster, more accessible, and typically more readily available, especially after hours (see Image. Axial Non-Contrast CT of Pott Puffy Tumor in a Girl Aged 8).[13][14]

Bone scintigraphy using technetium-99 or gallium is another imaging modality that is rarely used today. Although this technique is more sensitive than CT or MRI for detecting early osteomyelitis, its lower specificity and limited role make it less valuable when anatomical imaging and physical examination can be monitored over time.[8]

Laboratory evaluation for suspected PPT may include a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein, along with tests for suspected immunocompromising conditions. However, white blood cell counts and inflammatory markers may be normal in up to half of patients with PPT.[19]

Treatment / Management

Rapid diagnosis and prompt treatment of PPT are essential to reducing the risk of severe neurological complications. Studies have shown that the most effective management strategy for PPT involves a combination of systemic antibiotic therapy, surgical abscess drainage, debridement of devitalized tissue, and restoration of frontal sinus outflow.[8][3][4][5][11][14] Once PPT is suspected, the patient should be admitted and promptly started on broad-spectrum intravenous (IV) antibiotics, IV hydration, and analgesia. Imaging studies should be obtained immediately. If the diagnosis is confirmed, consultation with otolaryngology and neurosurgery is required.[13](B3)

Broad-Spectrum IV Antibiotics

Empiric antibiotic therapy should be initiated promptly to cover the most common pathogens, including gram-positive cocci and anaerobes. Ideally, selected antibiotics should penetrate the blood-brain barrier for intracranial coverage. Recommended options include penicillins (such as ampicillin-sulbactam and piperacillin-tazobactam), vancomycin, fluoroquinolones (such as ciprofloxacin), third- or fourth-generation cephalosporins (such as ceftriaxone and cefepime), and metronidazole.

Once culture and sensitivity results are available, antibiotic coverage can be refined for more targeted, long-term therapy. The duration of treatment varies, but for osteomyelitis, it is typically prolonged, often lasting 4 to 8 weeks postoperatively, and is administered via a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC). Consultation with an infectious disease specialist is standard practice to determine the appropriate type and duration of antibiotic therapy. While small extradural collections may be managed with IV antibiotics alone, aspiration or biopsy is still recommended to obtain material for culture and optimize treatment.

Surgery

The primary goal of surgery is to drain extracranial and intracranial abscesses, reestablish drainage from the affected sinus(es), and remove compromised bone. These steps are essential to achieving successful infection clearance, except in cases of the smallest infections. Historically, an open approach has been the standard of care due to its superior visualization of the frontal recess. However, this method is highly invasive, requiring a long incision and posing a risk of injury to the sensory and motor nerves of the forehead. In cases without significant bone devitalization or intracranial extension, endoscopic intranasal frontal sinusotomy, with or without trephination, is now the preferred approach due to its lower morbidity, shorter recovery time, and absence of external scarring.[4]

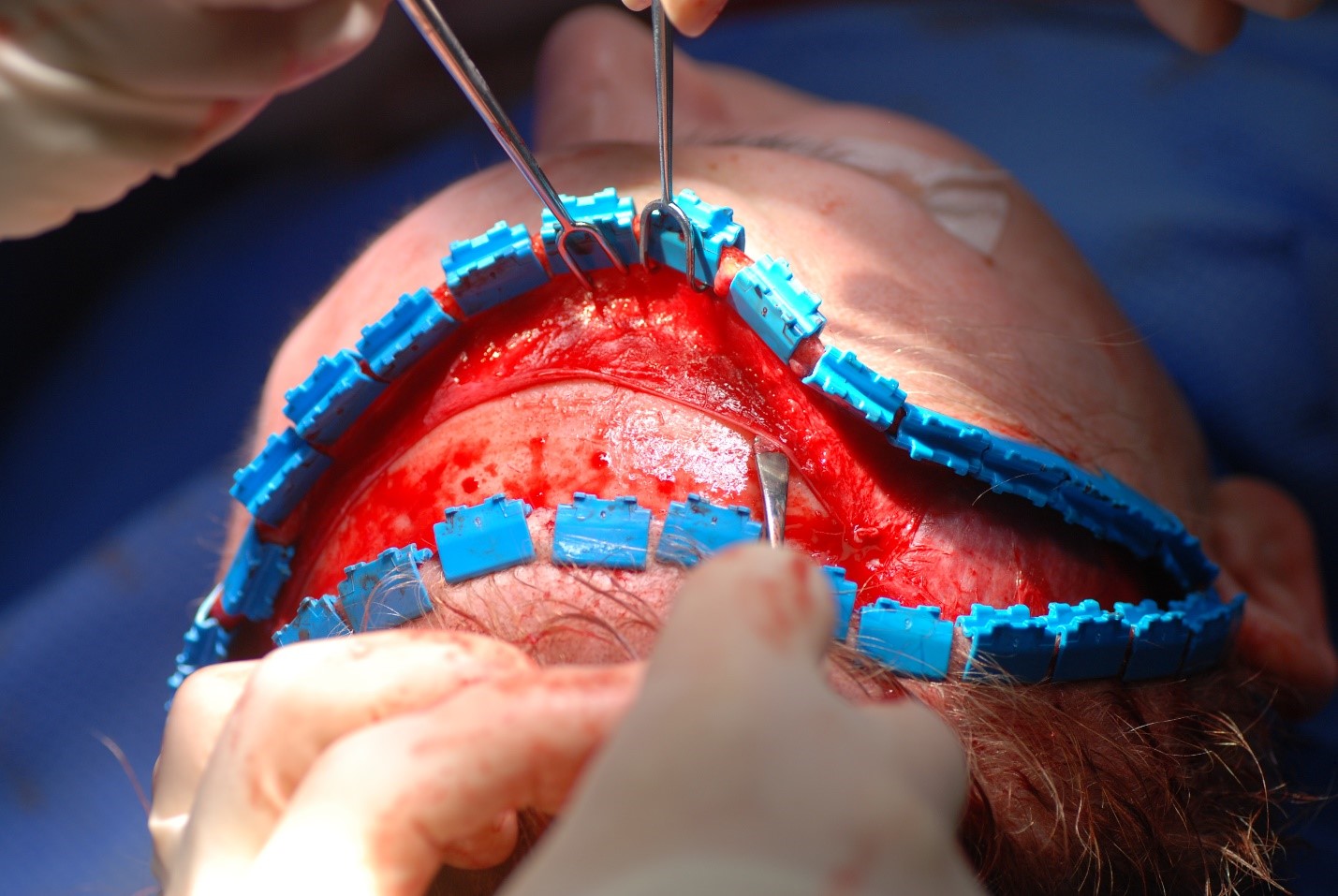

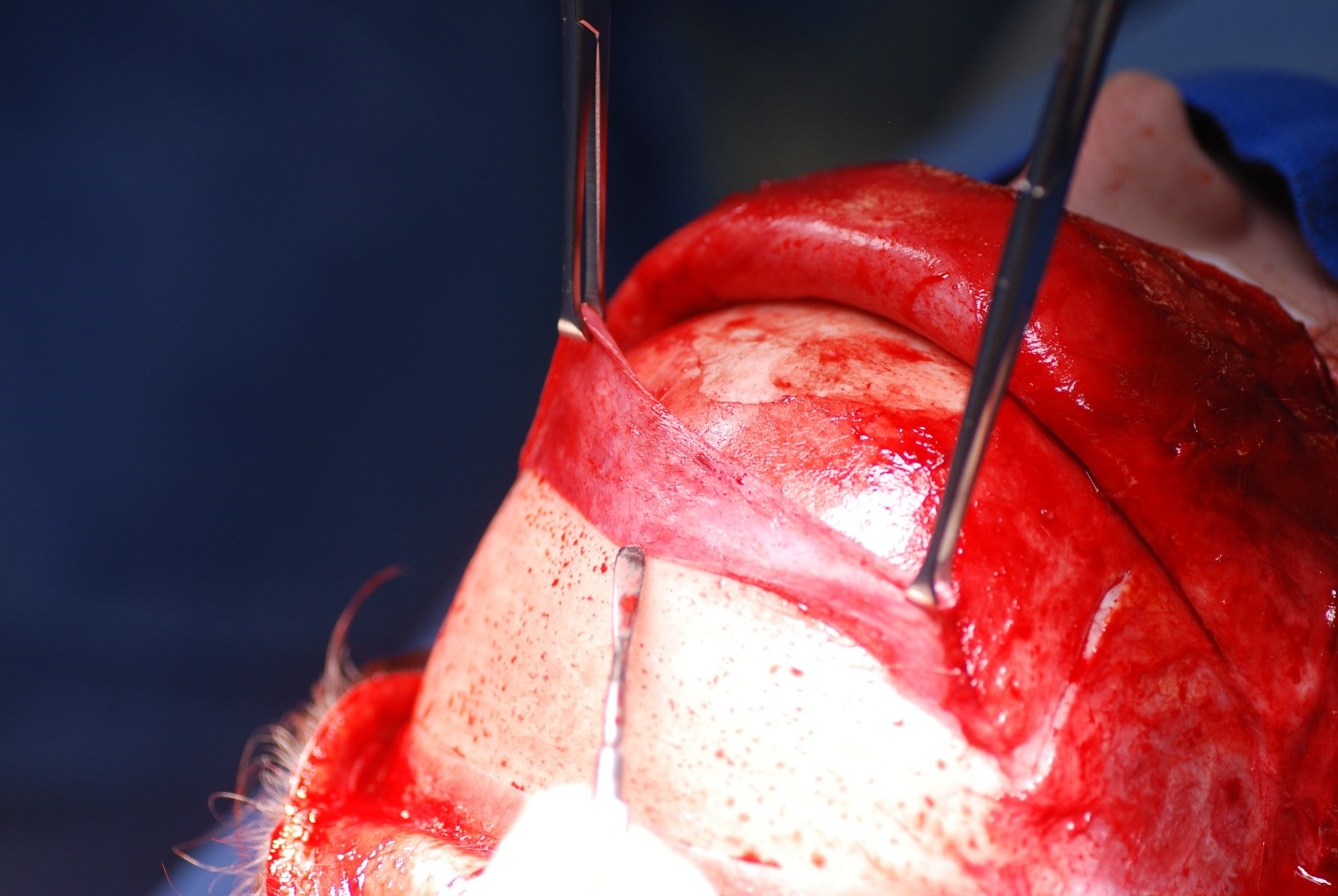

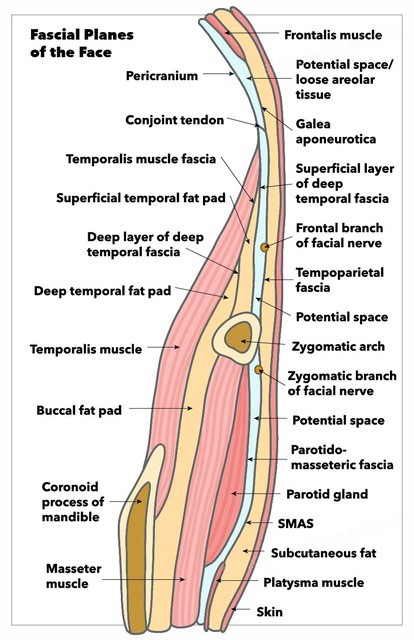

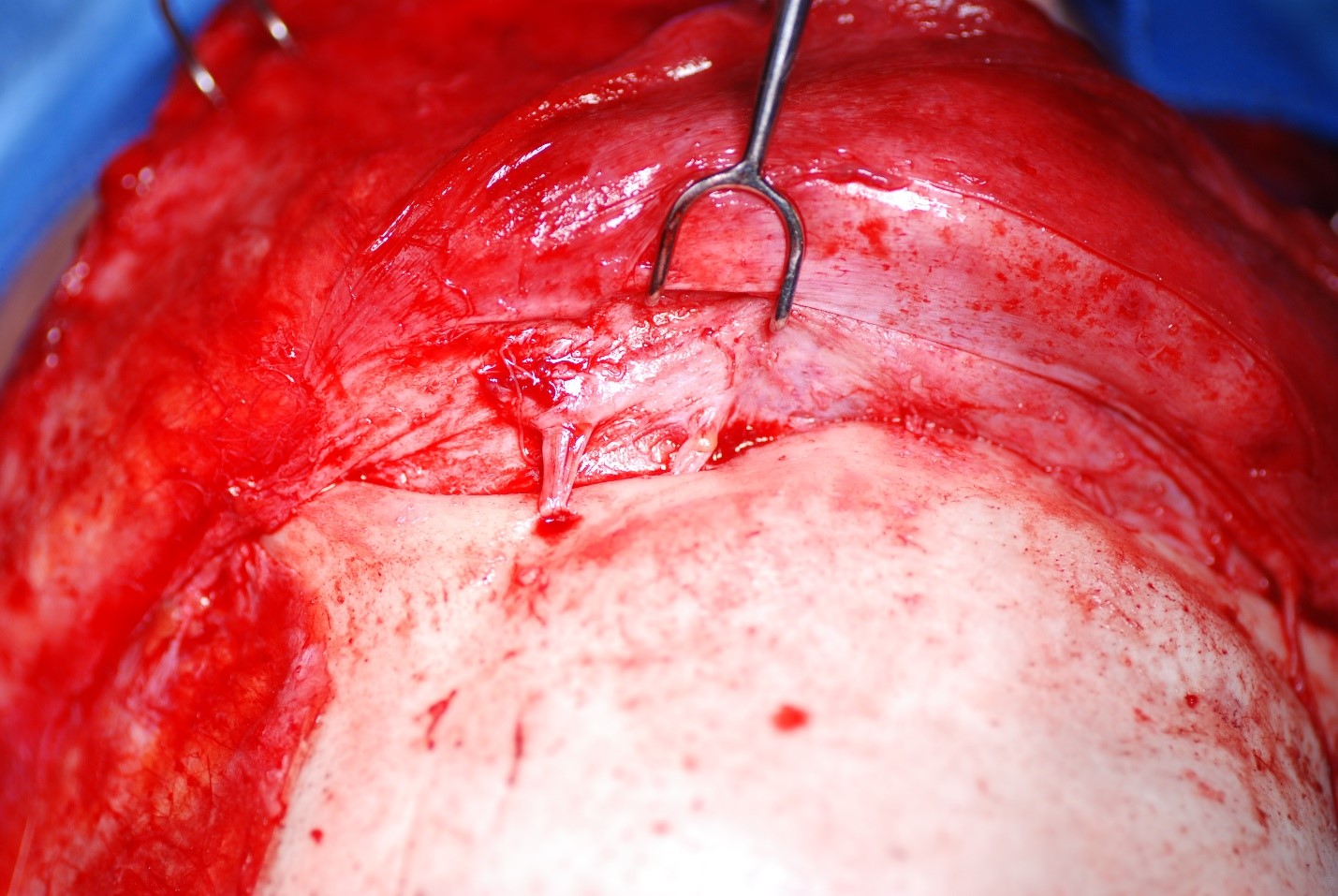

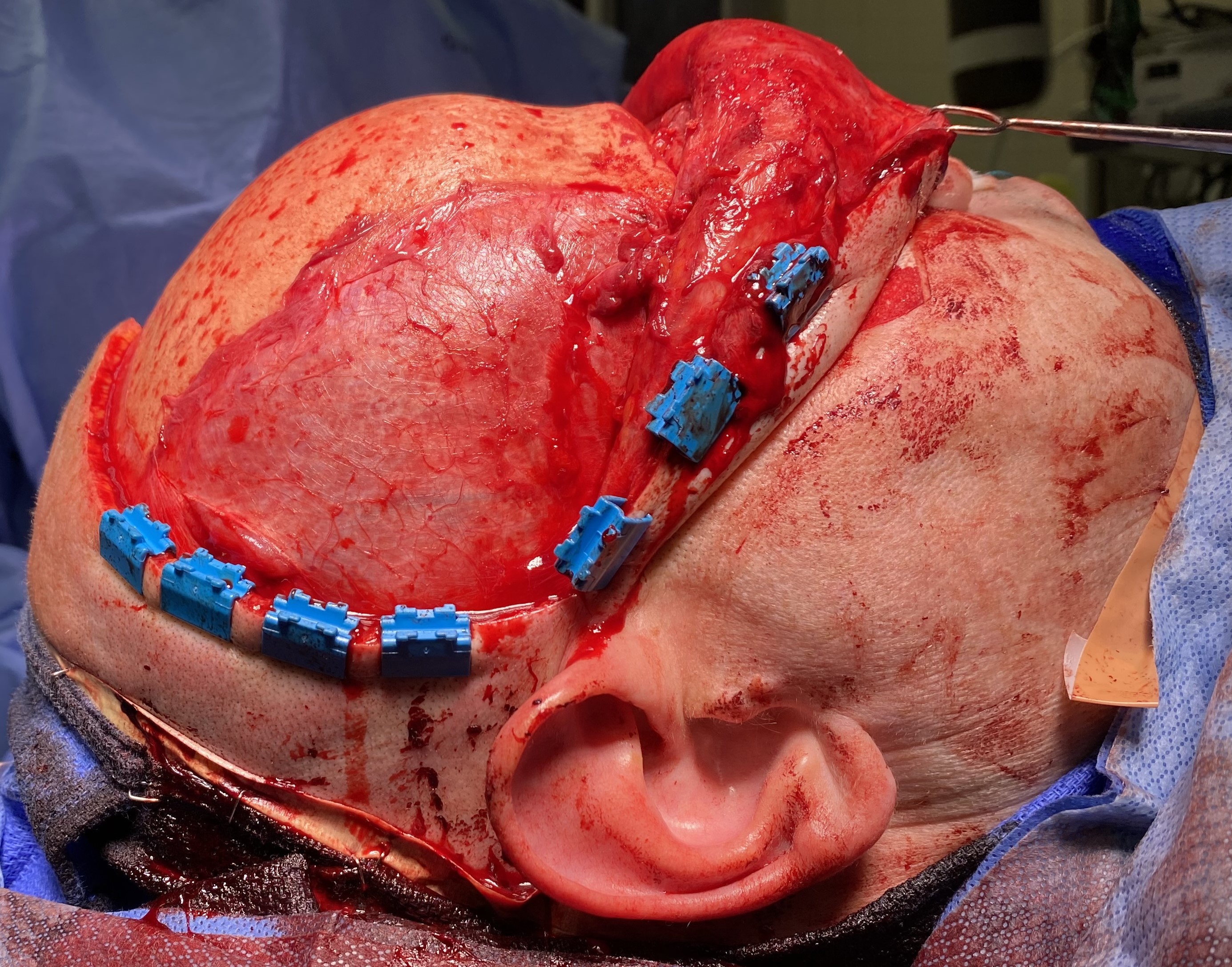

Craniotomy: A craniotomy is typically performed via a coronal approach to expose the frontal sinus, debride necrotic bone, and access intracranial structures.[8][4][11] The incision is made from ear to ear across the vertex of the scalp. Some surgeons include a wave or zig-zag pattern to break up the scar, whereas others make a straight incision for simplicity's sake (see Image. Coronal Approach to the Craniofacial Skeleton). In the central portion of the incision, dissection is carried out either down to the pericranium (if the surgeon anticipates needing a pericranial flap and prefers to elevate it separately from the forehead flap) or down to the bare skull (if no pericranial flap is anticipated, or if the surgeon prefers to elevate the pericranial flap from the deep surface of the forehead flap) (see Image. Periosteum Elevation Using a Freer Elevator). Laterally, the dissection proceeds down to the temporalis muscle fascia (deep temporal fascia), allowing for the elevation of the temporoparietal fascia (superficial temporal fascia) while preserving the frontal branch of the facial nerve within it (see Image. Fascial Planes of the Face and Musculature). To connect the central and lateral compartments, the intervening conjoint tendon must be divided. After this, elevating the coronal flap down to the level of the orbital rims requires minimal effort.(B3)

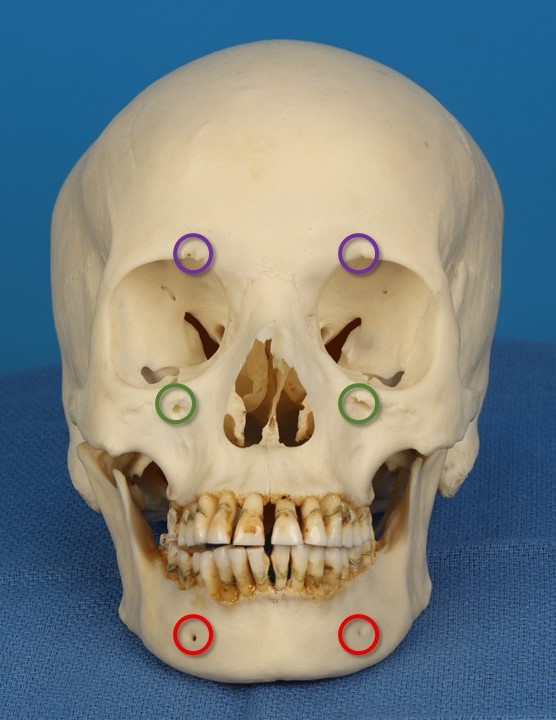

The supraorbital neurovascular bundles are typically found emerging from the skull via notches, though in rare cases, they may traverse foramina up to 1 cm above the supraorbital nerves. Care should be taken to avoid injuring these bundles, as well as the supratrochlear nerves, to preserve sensation to the forehead (see Image. Supraorbital and Supratrochlear Neurovascular Bundles). The supraorbital nerves are reliably located at or slightly medial to the point where the midpupillary line intersects the supraorbital rim, whereas the supratrochlear nerves are situated 1.5 to 2 cm lateral to the midline, emerging from the superomedial orbit (see Image. Trigeminal Foramina of the Face). Regardless of whether the supraorbital nerves remain intact at the brow, the patient should expect scalp numbness posterior to the coronal incision.

Once flap elevation is complete, necrotic bone can be debrided, and the frontal sinus irrigated. If needed, subperiosteal or epidural abscesses can be drained, and the frontal sinus outflow tracts can be enlarged as necessary (see Image. Coronal Approach to the Frontal Sinus). Frontal sinus obliteration may be considered for patients with recurrent episodes of PPT. This procedure involves exenterating all mucosa with a drill, plugging the outflow tracts with soft tissue, and filling the sinus with fat or a pericranial flap.[4][14] The pericranial flap can either be elevated separately from the forehead flap or the deep surface of the forehead flap, maintaining its pedicle on the supraorbital vessels in both instances (see Image. Pericranial Flap Elevation). In addition to predictable posterior scalp hypesthesia, the primary risks of this approach include forehead hypesthesia and forehead weakness due to injury to the supraorbital and facial nerves, respectively.(B3)

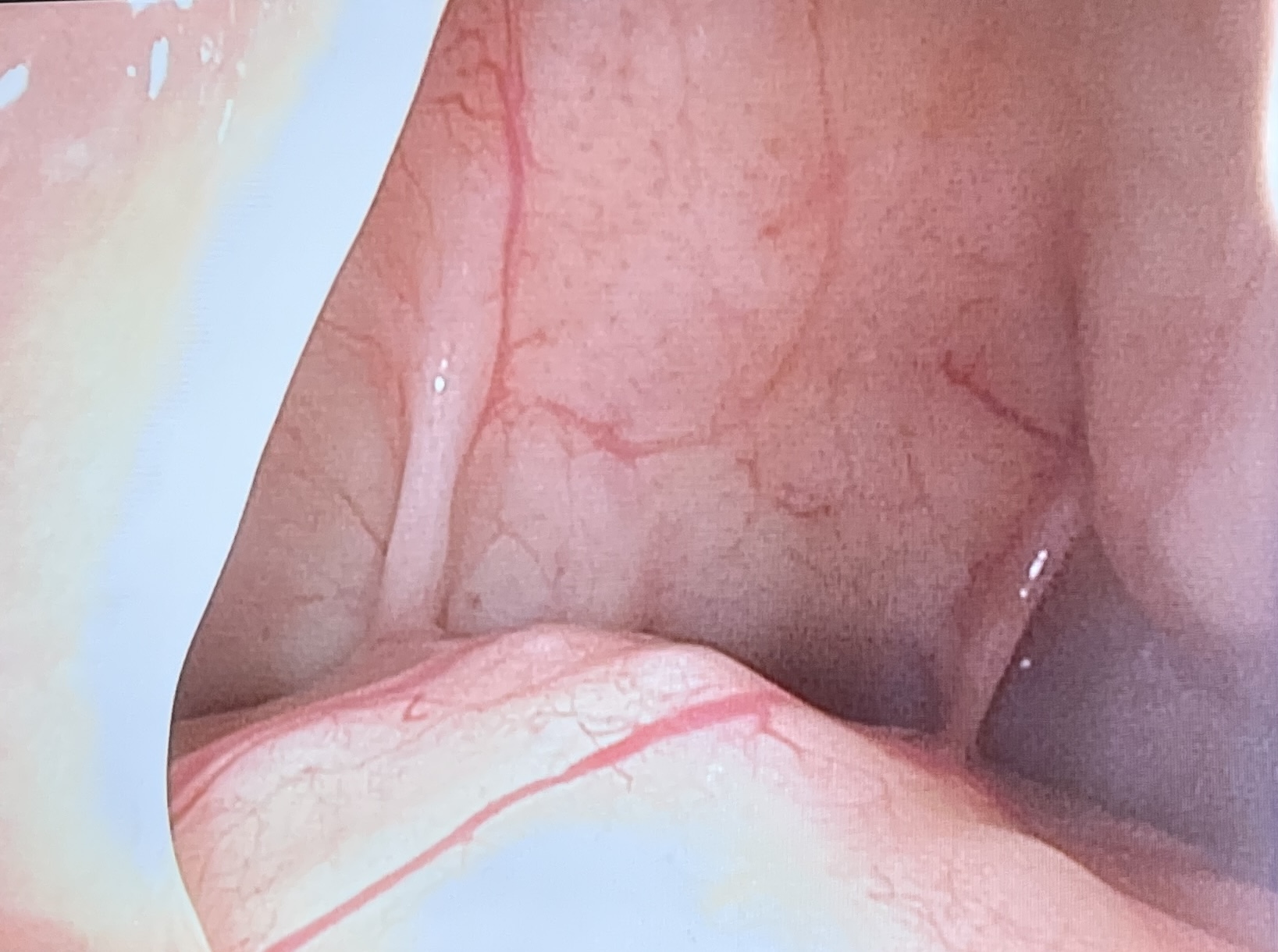

Endoscopic frontal sinusotomy: This procedure is performed endonasally, significantly reducing the morbidity associated with access to the frontal sinus. However, this technique is unsuitable when bone debridement is necessary (see Image. Endoscopic View of the Frontal Sinus).[4][20][21][22] Accessing the frontal outflow tract, which drains into the middle meatus beneath the middle turbinate, necessitates the removal of the uncinate process of the ethmoid bone, the ethmoid bulla, and the agger nasi (the most anterior ethmoid) cell. The frontal outflow tract is consistently located posterior to the agger nasi cell, lateral to the middle turbinate, medial to the lamina papyracea, and anterior to the ethmoid bulla. Diseased mucosa within the nasofrontal duct can be excised, and the outflow tract may be enlarged, if needed, by removing surrounding ethmoid air cells or using balloon dilation.(B2)

Trephination: Trephination may be necessary, in addition to either a coronal or endoscopic approach, if there is an epidural abscess deep to the frontal sinus or if the anatomy of the frontal sinus prevents complete drainage via endoscopic sinusotomy.[8][4][14] For frontal sinus trephination, a skin incision of approximately 2 cm is made above, within, or below the medial brow or within the upper eyelid supratarsal crease, similar to a blepharoplasty approach (see Image. Approaches for Frontal Sinus Trephination). The incision is extended through the periosteum, which is then elevated to expose the frontal bone. A small drill, such as a 4-mm cutting bur, is used to perforate the frontal bone, creating an osteotomy just large enough (6-8 mm in diameter) to provide access for a camera or endoscopic instrumentation.(B3)

Alternatively, a "mini trephination" technique may be used, which involves a shorter incision and a 4-mm drill specifically designed to penetrate the frontal sinus without violating the skull base.[23] If necessary, an IV angiocatheter can be sutured into the incision to allow for postoperative irrigation and drainage of the sinus for a few days. When accessing the epidural space, a similar protocol is followed, with a longer incision made through the periosteum and a trephination drill used to core out a circular piece of bone, which may be replaced at the surgeon's discretion.

Differential Diagnosis

Additional conditions that may mimic PPT include:

- Abscess of the forehead

- Cellulitis of the forehead

- Frontal hematoma, with or without secondary infection

- Frontal sinus fracture

- Frontal bone fracture

- Lipoma

- Osteoma

- Epidermal inclusion cyst

- Hemangioma

- Basal cell carcinoma

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Merkel cell carcinoma

- Dermatofibrosarcoma protruberans

Prognosis

The morbidity, mortality, and prognosis of PPT in an individual case depend on prompt recognition and early treatment. If the infection is not addressed in a timely manner, intracranial complications are more likely to develop, worsening the prognosis for full recovery.[12][3][5][13][14] Due to the rarity of PPT with the widespread use of antibiotics, determining an exact mortality rate is challenging; however, reported figures in the literature range from 5% to 17%.[24][25]

Complications

Intracranial Complications

Intracranial complications are the most common sequelae of PPT, occurring in 60% to 85% of cases, with children affected 3 times as often as adults.[2] Epidural and subdural abscesses are the most frequent intracranial complications.[7][8][11] Intracranial complications develop either via septic thrombophlebitis or by direct extension of the infection.[4] Delayed treatment significantly increases the incidence and severity of intracranial involvement.

Common intracranial complications include:

- Epidural abscess

- Subdural abscess

- Frontal lobe abscess

- Meningitis

- Encephalitis

- Dural venous sinus thrombosis

- Cavernous sinus thrombosis

- Cortical venous thrombosis

Intraorbital Complications

Direct extension of the infection through the floor of the frontal sinus or the lateral wall of the ethmoid air cells can lead to orbital complications. These include orbital cellulitis and orbital abscess, both of which require ophthalmological consultation.[8]

Surgical Complications

The risks associated with surgery depend on the operative approach used to manage the infection.

- Potential complications of endoscopic sinusotomy include infection recurrence or persistence, inadequate bony debridement, epistaxis, obstructive intranasal scarring (synechiae), frontal sinus outflow tract obstruction, diplopia, retrobulbar hematoma, vision loss, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak, and meningitis.

- A coronal approach carries many of the same risks and also increases the likelihood of poor scarring and alopecia due to the incision length. Additionally, motor and sensory nerve damage may result in forehead hypesthesia and/or paresis.

- Trephination, an external approach, also poses the risk of a visible scar, forehead numbness, CSF leak, meningitis, epistaxis, frontal sinus outflow tract obstruction, and infection recurrence.[4]

Consultations

The extent and severity of the infection determine the specialists required for the treatment of patients with this condition. In addition to the emergency medicine provider who initially evaluates the patient, a radiologist or neuroradiologist is needed to confirm the diagnosis of PPT.

Frontal sinusotomy is typically performed by an otolaryngologist, pediatric otolaryngologist, or rhinologist, while a neurosurgeon is required for cases with intracranial extension. If the infection spreads to the orbit, ophthalmological consultation is necessary. An infectious disease specialist is usually consulted to determine the appropriate antibiotic regimen, including the route of administration and duration of therapy. If neurological complications arise, an intensivist oversees the patient’s care with support from critical care nurses. Long-term rehabilitation may involve physical therapy, occupational therapy, and, if needed, speech and swallowing therapy.[8][13]

Deterrence and Patient Education

PPT is an uncommon condition but is relatively easy to suspect and diagnose due to its characteristic forehead swelling and radiographic findings. Successful outcomes depend on timely medical evaluation and prompt initiation of appropriate antibiotic therapy to be administered to patients. Most upper respiratory tract infections resolve spontaneously; however, over-the-counter treatments such as sinonasal saline irrigation and fluticasone or mometasone nasal spray can help reduce the duration and severity of symptoms.[26][27][28] However, medical care should be sought when a frontal headache or pain between the eyes, fever, purulent rhinorrhea, and glabellar, forehead, or periorbital swelling develops.

Pearls and Other Issues

Key facts to keep in mind regarding "Pott puffy syndrome" include:

- PPT refers to the forehead or glabellar swelling caused by frontal bone osteomyelitis with an associated subperiosteal abscess.

- PPT is most commonly a complication of sinusitis but can also result due to trauma.

- Although PPT is rare, it is most frequently seen in pediatric and young adolescent patients due to active frontal sinus pneumatization.

- The most common presentation of PPT is forehead swelling, fever, rhinorrhea, and headache.

- PPT is typically polymicrobial, involving Streptococci, anaerobes, and Staphylococci.

- Once suspected, management should include broad-spectrum IV antibiotics, IV hydration, analgesia, and prompt imaging.

- Neurological symptoms such as obtundation, altered mental status, or seizures should heighten suspicion of intracranial involvement.

- Head CT with contrast is the preferred initial imaging modality, while brain MRI is superior for assessing intracranial involvement.

- Brain MRI is the preferred modality for assessing infection resolution during follow-up, as it avoids radiation exposure.

- Early specialist consultation, particularly with otolaryngology and neurosurgery, is essential for optimal management.

- Effective treatment of PPT requires a combination of surgical intervention and prolonged IV antibiotic therapy.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Although PPT is a rare complication of bacterial rhinosinusitis, its prompt recognition by emergency or primary care teams is crucial for a successful patient outcome. Diagnosis confirmation requires the expertise of a radiologist and imaging technicians specializing in CT or MRI. Treatment initiation is guided by the recommendations of an infectious disease specialist, informed by the findings of microbiology technicians.

As osteomyelitis often requires prolonged antibiotic therapy, a PICC line is typically placed by a vascular access nurse or an interventional radiologist. If surgery is necessary, an otolaryngologist or rhinologist, anesthesia provider, surgical technician, operating room nurse, and recovery room nurse will be involved. In cases of intracranial complications, a neurosurgeon and critical care team will also be required. Given the potential severity of PPT, many healthcare providers are typically involved in the patient's care. Efficient and respectful coordination among these providers is essential to achieving optimal patient outcomes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Pott Puffy Tumor in a Girl Aged 8 on Day 12 of Infection. Sagittal view at presentation showed significant fullness over the area corresponding to the frontal sinus, indicative of swelling associated with a Pott puffy tumor.

Suwan PT, Mogal S, Chaudhary S. Pott's puffy tumor: an uncommon clinical entity. Case Rep Pediatr. 2012;2012:386104.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Axial Contrast-Enhanced CT of Pott Puffy Tumor in a Girl Aged 8. Axial CT with contrast demonstrating subperiosteal (arrow) and epidural (circle) abscesses in a girl aged 8 with a Pott puffy tumor.

Suwan PT, Mogal S, Chaudhary S. Pott's puffy tumor: an uncommon clinical entity. Case Rep Pediatr. 2012;2012:386104.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Axial Non-Contrast CT of Pott Puffy Tumor in a Girl Aged 8. Axial CT without contrast at presentation showing erosion of the anterior and posterior tables of the frontal sinus (arrows), frontal sinus opacification (arrowhead), and soft tissue swelling of the forehead, consistent with a Pott puffy tumor.

Suwan PT, Mogal S, Chaudhary S. Pott's puffy tumor: an uncommon clinical entity. Case Rep Pediatr. 2012;2012:386104.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Sagittal MRI of Pott Puffy Tumor in a Girl Aged 8. Sagittal MRI demonstrating an abscess in the frontal scalp (arrow) and an adjacent epidural abscess (circle) in a girl aged 8 with a Pott puffy tumor.

Suwan PT, Mogal S, Chaudhary S. Pott's puffy tumor: an uncommon clinical entity. Case Rep Pediatr. 2012;2012:386104.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Fascial Planes of the Face. This illustration depicts the fascial planes of the face, highlighting the continuity of the frontalis muscle, galea aponeurotica, temporoparietal fascia, superficial musculoaponeurotic system, platysma, and the location of the facial nerve.

Contributed by K Humphreys and MH Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

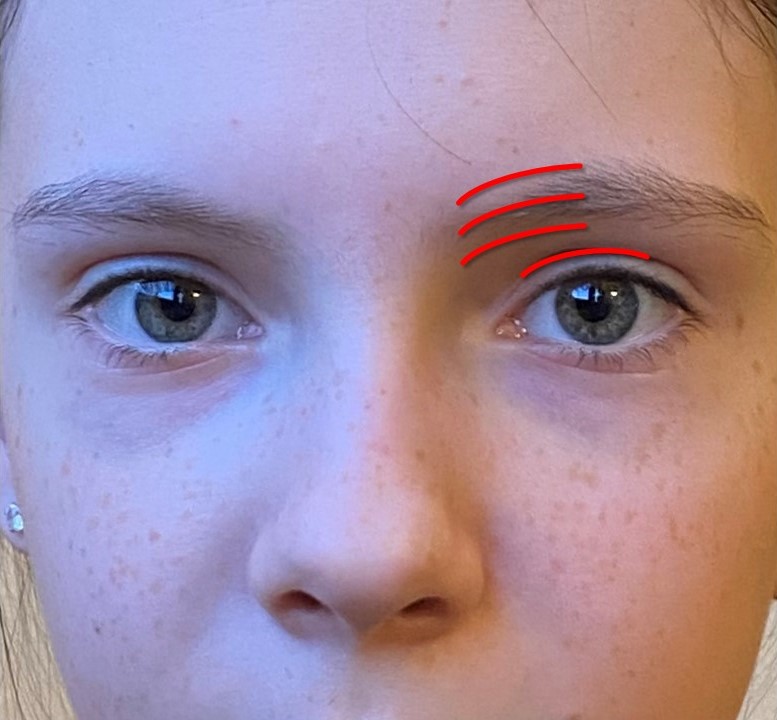

Supraorbital and Supratrochlear Neurovascular Bundles. The supraorbital and supratrochlear neurovascular bundles are visible above the patient’s left orbit. The supraorbital bundle exits through a foramen at the midpupillary line, whereas the supratrochlear bundle passes through a shallow notch approximately 1.5 to 2 cm lateral to the facial midline.

Contributed by MH Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Coronal Approach to the Craniofacial Skeleton. This surgical exposure grants access to the frontal sinus, naso-orbito-ethmoid region, zygomatic arches, orbital roofs, and anterior skull base. Structures at risk include the frontal branches of the facial nerve and the supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves.

Contributed by MH Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Approaches For Frontal Sinus Trephination. A roughly 2 cm incision can be made inferior to, within, or superior to the medial brow or within the supratarsal crease. Dissection continues down to the periosteum, which is incised and elevated to allow access for the trephination drill.

Contributed by COM Hohman and MH Hohman, MD, FACS

References

Ravitch MM. Surgery in 1776. Annals of surgery. 1977 Sep:186(3):291-300 [PubMed PMID: 329781]

Skomro R, McClean KL. Frontal osteomyelitis (Pott's puffy tumour) associated with Pasteurella multocida-A case report and review of the literature. The Canadian journal of infectious diseases = Journal canadien des maladies infectieuses. 1998 Mar:9(2):115-21 [PubMed PMID: 22451778]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJoo MJ, Schapira KE. Pott's Puffy Tumor: A Potentially Deadly Complication of Sinusitis. Cureus. 2019 Dec 11:11(12):e6351. doi: 10.7759/cureus.6351. Epub 2019 Dec 11 [PubMed PMID: 31938637]

Jung J, Lee HC, Park IH, Lee HM. Endoscopic Endonasal Treatment of a Pott's Puffy Tumor. Clinical and experimental otorhinolaryngology. 2012 Jun:5(2):112-5. doi: 10.3342/ceo.2012.5.2.112. Epub 2011 Feb 7 [PubMed PMID: 22737293]

Bhalla V, Khan N, Isles M. Pott's puffy tumour: the usefulness of MRI in complicated sinusitis. Journal of surgical case reports. 2016 Mar 21:2016(3):. pii: rjw038. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjw038. Epub 2016 Mar 21 [PubMed PMID: 27001196]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKoltsidopoulos P, Papageorgiou E, Skoulakis C. Acute sinusitis complicated with Pott puffy tumour. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 2019 Feb 11:191(6):E165. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.181025. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30745402]

Apostolakos D, Tang I. Image Diagnosis: Pott Puffy Tumor. The Permanente journal. 2016 Summer:20(3):15-157. doi: 10.7812/TPP/15-157. Epub 2016 Jun 24 [PubMed PMID: 27352411]

Sharma P, Sharma S, Gupta N, Kochar P, Kumar Y. Pott puffy tumor. Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center). 2017 Apr:30(2):179-181 [PubMed PMID: 28405074]

Wu CT, Huang JL, Hsia SH, Lee HY, Lin JJ. Pott's puffy tumor after acupuncture therapy. European journal of pediatrics. 2009 Sep:168(9):1147-9. doi: 10.1007/s00431-008-0892-x. Epub 2008 Dec 5 [PubMed PMID: 19057925]

Khan MA. Pott's puffy tumor: a rare complication of mastoiditis. Pediatric neurosurgery. 2006:42(2):125-8 [PubMed PMID: 16465085]

Perić A, Milojević M, Ivetić D. A Pott's Puffy Tumor Associated with Epidural - Cutaneous Fistula and Epidural Abscess: Case Report. Balkan medical journal. 2017 May 5:34(3):284-287. doi: 10.4274/balkanmedj.2016.1304. Epub 2017 Apr 13 [PubMed PMID: 28443599]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHasan I, Smith SF, Hammond-Kenny A. Potts puffy tumour: a rare but important diagnosis. Journal of surgical case reports. 2019 Apr:2019(4):rjz099. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjz099. Epub 2019 Apr 3 [PubMed PMID: 30967934]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceur Rehman A, Muhammad MN, Moallam FA. Pott puffy tumor: a rare complication of sinusitis. Annals of Saudi medicine. 2013 Jan-Feb:33(1):79-80 [PubMed PMID: 22634502]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLauria RA, Laffitte Fernandes F, Brito TP, Pereira PS, Chone CT. Extensive Frontoparietal Abscess: Complication of Frontal Sinusitis (Pott's Puffy Tumor). Case reports in otolaryngology. 2014:2014():632464. doi: 10.1155/2014/632464. Epub 2014 May 25 [PubMed PMID: 24971185]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceForgie SE, Marrie TJ. Pott's puffy tumor. The American journal of medicine. 2008 Dec:121(12):1041-2. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.08.018. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19028195]

McCallum JE, Brand E, Selker RG. Osteomyelitis of the skull in chronic granulomatous disease of childhood. Case report. Journal of neurosurgery. 1974 Jun:40(6):764-6 [PubMed PMID: 4596996]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVerbon A, Husni RN, Gordon SM, Lavertu P, Keys TF. Pott's puffy tumor due to Haemophilus influenzae: case report and review. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 1996 Dec:23(6):1305-7 [PubMed PMID: 8953076]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFeder HM Jr, Cates KL, Cementina AM. Pott puffy tumor: a serious occult infection. Pediatrics. 1987 Apr:79(4):625-9 [PubMed PMID: 3822683]

Bullitt E, Lehman RA. Osteomyelitis of the skull. Surgical neurology. 1979 Mar:11(3):163-6 [PubMed PMID: 473006]

Leong SC. Minimally Invasive Surgery for Pott's Puffy Tumor: Is It Time for a Paradigm Shift in Managing a 250-Year-Old Problem? The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2017 Jun:126(6):433-437. doi: 10.1177/0003489417698497. Epub 2017 Apr 4 [PubMed PMID: 28376662]

van der Poel NA, Hansen FS, Georgalas C, Fokkens WJ. Minimally invasive treatment of patients with Pott's puffy tumour with or without endocranial extension - a case series of six patients: Our Experience. Clinical otolaryngology : official journal of ENT-UK ; official journal of Netherlands Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology & Cervico-Facial Surgery. 2016 Oct:41(5):596-601. doi: 10.1111/coa.12538. Epub 2016 Feb 8 [PubMed PMID: 26382235]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDeutsch E, Hevron I, Eilon A. Pott's puffy tumor treated by endoscopic frontal sinusotomy. Rhinology. 2000 Dec:38(4):177-80 [PubMed PMID: 11190752]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMcIntosh DL, Mahadevan M. Frontal sinus mini-trephination for acute sinusitis complicated by intracranial infection. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2007 Oct:71(10):1573-7 [PubMed PMID: 17628703]

Adejumo A, Ogunlesi O, Siddiqui A, Sivapalan V, Alao O. Pott puffy tumor complicating frontal sinusitis. The American journal of the medical sciences. 2010 Jul:340(1):79. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181bdb5b5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20442649]

Tsai BY, Lin KL, Lin TY, Chiu CH, Lee WJ, Hsia SH, Wu CT, Wang HS. Pott's puffy tumor in children. Child's nervous system : ChNS : official journal of the International Society for Pediatric Neurosurgery. 2010 Jan:26(1):53-60. doi: 10.1007/s00381-009-0954-z. Epub 2009 Sep 2 [PubMed PMID: 19727764]

Pynnonen MA, Mukerji SS, Kim HM, Adams ME, Terrell JE. Nasal saline for chronic sinonasal symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 2007 Nov:133(11):1115-20 [PubMed PMID: 18025315]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceZalmanovici Trestioreanu A, Yaphe J. Intranasal steroids for acute sinusitis. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2013 Dec 2:2013(12):CD005149. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005149.pub4. Epub 2013 Dec 2 [PubMed PMID: 24293353]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKeith PK, Dymek A, Pfaar O, Fokkens W, Yun Kirby S, Wu W, Garris C, Topors N, Lee LA. Fluticasone furoate nasal spray reduces symptoms of uncomplicated acute rhinosinusitis: a randomised placebo-controlled study. Primary care respiratory journal : journal of the General Practice Airways Group. 2012 Sep:21(3):267-75. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2012.00039. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22614920]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence