Introduction

Sacroiliac joint injury (SIJ) is a common cause of low back pain (LBP). Posterior pelvic joint pain is frequently used to describe SIJ dysfunction. This articulation connects the spine and pelvis and may be traumatically dislocated in high-energy events, such as motor vehicle accidents, representing a true orthopedic emergency.

The SIJ connects the iliac and sacral auricular surfaces. Injury to this region often produces significant pain localized to the posterior low back and buttock, although referral patterns may vary.[1] The SIJ experiences shearing, torsion, rotational, and tensile forces. Based on its geometry and load-bearing function, the joint has been analogized to a “Chinese finger trap.”

The SIJ plays a critical role in ambulation, as it represents the sole orthopedic connection between the upper and lower body. Structurally, the SIJ is an amphiarthrosis, similar to the pubic symphysis, characterized by limited motion via cartilaginous connections and a relatively stiff synovial joint containing synovial fluid. Sacral and iliac articular surfaces are coated with hyaline cartilage, while dense fibrous tissue reinforces the joint. Normal SIJ motion is limited to a few degrees.

Diagnosing SIJ pathology can be challenging. One difficulty in evaluating SIJ injury is distinguishing it from LBP (lumbago). Specialized provocation tests and diagnostic imaging can assist in making this distinction. The SIJ is a significant contributor to LBP, responsible for about 15% to 30% of cases, and should be routinely considered in differential diagnoses.[2] Pregnant women are particularly vulnerable due to hormonal joint laxity. SIJ fusion reduces joint laxity between the ages of 40 and 50. Pregnancy or fusion-related changes may result in hypermobility or hypomobility, which can exacerbate SIJ pain. Osteoarthritis is a frequent contributor to SIJ dysfunction.[3]

Multiple etiologies and contributing factors underlie SIJ injury. Symptom overlap with other sources of LBP, along with the diverse origins of SIJ dysfunction, complicates diagnosis and management.[4] SIJ injury can be acute, but pain persisting beyond 3 months defines chronic SIJ pain, which occurs when free nerve endings within the joint degenerate or become chronically activated. Pain may be constant or intermittent. Exclusion of lumbar pathology is essential before confirming SIJ dysfunction as the primary cause of back pain, with exceptions including trauma and pregnancy. Infectious causes of SIJ pain are uncommon but can occur in both pediatric and adult populations and are often overlooked.[5]

Excessive joint mobility can result in pain within the SIJ. Conversely, hypomobility is a hallmark of ankylosing spondylitis, a common cause of inflammatory SIJ injury. SIJ dysfunction frequently coexists with mechanical LBP. The SIJ may also be the site of referred pain from the lumbar vertebrae rather than the primary origin. For example, degenerative disc disease at L5 to S1 may be perceived as SIJ pain, although the source is located higher in the lumbar spine.

Multiple referral patterns are observed in SIJ injury, including the posterior thigh, knee, or foot. The posterior thigh is the most common site, occurring in approximately 50% of patients.[6][7][8] Management is further complicated by the absence of clearly defined diagnostic and treatment guidelines. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the preferred imaging modality for evaluating SIJ dysfunction. In addition, radiography-guided anesthetic injection provides a reliable method for confirming SIJ pathology as the source of pain in many cases.

The SIJ is a frequent target for intervention in chronic LBP.[9][10] Conservative management typically includes physical therapy, home exercise programs, and over-the-counter (OTC) analgesics such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or acetaminophen. Corticosteroid injections and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) are viable options when conservative strategies are insufficient. SIJ fusion may be indicated in severe, refractory cases.[11] Patient education is a critical component of management, emphasizing posture, safe lifting techniques, stretching, and regular exercise. Weight reduction should be considered in patients with elevated body mass index to reduce mechanical stress on the joint.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

SIJ injuries may result from a variety of etiologies. Approximately 88% of SIJ pathologies arise from either repetitive microtrauma or acute trauma, with a notably high prevalence among athletes. Pregnancy accounts for 20% of cases, while 4% are idiopathic.[12] Trauma associated with pelvic ring injuries represents a specific example of SIJ injury. Pelvic ring injuries are classified into 3 main types: anteroposterior compression, lateral compression, and vertical shear. SIJ injuries may manifest as incomplete dislocations, complete dislocations, or fracture-dislocations.

Three types of fractures are associated with SIJ injury. A type 1 fracture involves the anterior aspect of the S2 foramen, producing a large crescent-shaped fragment that remains stable. Less than 1/3 of the SIJ is involved, with minimal ligament injury compared to the other fracture types. Type 2 fractures occur between the anterior aspects of the S1 and S2 foramina, generating a smaller crescent-shaped fragment than a type 1 fracture. These fractures involve 1/3 to 2/3 of the SIJ. Type 3 fractures encompass the superior and posterior aspects of the SIJ up to the S1 nerve root. Greater than 2/3 of the joint is involved, with a higher degree of ligament disruption, although the fragment is typically smaller than in type 1 or 2 fractures. Posterior fracture-dislocations of the SIJ involve variable disruption of the ligament complex.[13]

The L5 nerve root crosses the sacral ala approximately 2 cm medial to the SIJ. This nerve root may be compromised in the presence of joint injury, producing radicular pain. SIJ innervation derives from the ventral rami of L4 and L5, the dorsal rami of L5 to S2, and the superior gluteal nerve. Damage to these neural structures can produce neuropathic SIJ pain. Generalized gluteal pain may arise from SIJ lesions or injury to adjacent nerves, producing radiculopathy. Direct trauma to the S1 nerve root during SIJ injury is another cause of radiculopathy.

During pregnancy, relaxin-mediated ligamentous laxity increases mobility of the pelvic joints, including the SIJ. Additional stress is placed on the SIJ as the pelvis widens and the hips rotate, producing pain that may be unilateral or bilateral.[14] SIJ dysfunction in pregnancy arises from multiple biomechanical mechanisms, including weight gain, altered posture, increased intra-abdominal and intrauterine pressures, and ligamentous laxity of the spine and pelvis.[15] Patients with pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain have higher disability rates compared with those experiencing mechanical LBP.[16] Reported risk factors include forceps delivery, intense contractions, and fetal macrosomia, while multiparity, precipitous labor, and a rapid 2nd stage of labor further contribute to the condition.[17][18][19]

Anatomical variations can predispose to SIJ injury. Increased lumbar lordosis and anterior pelvic tilt predispose to SIJ dysfunction.[20] Patients with underdeveloped musculature may experience postural imbalances, such as leg-length discrepancy.

Degenerative and inflammatory conditions also play a role in SIJ pathology. Osteoarthritis produces characteristic radiographic changes, including joint-space narrowing, osteophyte formation, and sclerosis. Inflammatory arthritis most often manifests as ankylosing spondylitis, which progressively erodes the SIJ, producing pain and functional impairment. Subchondral edema represents the earliest imaging finding of sacroiliitis. The joint space widens, becomes sclerotic, and ultimately fuses as erosions advance.[21] Severity is graded from 0 (normal) to 4 (complete ankylosis).[22] Risk factors for accelerated progression include active inflammation with elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) levels or abnormal MRI findings, smoking history, male sex, and human leukocyte antigen B27 (HLA-B27) positivity.

Infectious causes of SIJ pathology are often overlooked. Risk factors include intravenous drug abuse, immunosuppression, pregnancy, end-stage renal disease requiring hemodialysis, penetrating trauma, infective endocarditis, sepsis, and tuberculosis. The most common organisms are Staphylococcus aureus, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and Salmonella. Skeletal tuberculosis accounts for 3% to 5% of all cases, 10% of which involve the joint. Salmonella infection leading to SIJ involvement occurs more frequently in patients with sickle cell disease for unclear reasons.

Epidemiology

Approximately 13% of patients with chronic LBP have SIJ dysfunction. Between 15% and 30% of LBP is attributable to SIJ pathology.[23] A study reported that 1 in 6 patients with newly diagnosed inflammatory bowel disease demonstrated MRI findings consistent with axial spondyloarthropathy, 40% of whom were asymptomatic at diagnosis.[24]

Lateral compression involving the SIJ accounts for up to 80% of pelvic ring injuries. Crescent fracture-dislocations represent 12% of cases. Abnormal SIJ movement is observed in 20% of college students and in 8% to 16% of asymptomatic individuals.

More than 80% of patients report clinically significant pain relief following SIJ fusion compared to 25% in the nonoperative group. Approximately 3% of patients undergoing fusion require revision surgery. Surgical intervention generally necessitates at least 75% pain reduction following an SIJ diagnostic injection before proceeding to fusion.[25][26]

Pathophysiology

"SIJ injury" is a broad term that encompasses conditions ranging from enthesitis and blunt trauma to infection and complex pelvic fractures. Open-book pelvic fractures are characterized by pubic symphysis diastasis or pubic rami fractures, typically associated with posterior pelvic disruption involving the SIJ and potential injury to the femoral artery.[27]

The surface area of the SIJ is slightly larger in men than in women, with a typically thinner sacrocartilaginous alignment that suggests greater tolerance to biomechanical load in men. In women, the SIJ demonstrates greater mobility due to the lower curvature of the articular surface, an adaptation that facilitates vaginal childbirth. These anatomical differences contribute to distinct biomechanical and biophysical properties, with women exhibiting higher rates of SIJ misalignment and a correspondingly increased prevalence of LBP.

Previous studies from Ulas et al demonstrated that the “typical” SIJ shape is observed more frequently in men (85.9%, compared to 37.9% in women). Accordingly, SIJ shape variants are significantly more common in women. The bipartite iliac bone plate occurs most frequently in women (21.9% vs 0.7% in men), followed by the accessory joint facet (12.7% vs 4.1% in men). These findings are clinically relevant because degenerative and inflammatory SIJ changes are more often associated with anatomically atypical joints.[28]

Histopathology

Distinct cartilage types cover the articular surfaces of the SIJ. The sacral surface is primarily composed of hyaline cartilage (approximately 1.18 mm thick), which provides elastic properties that reduce friction and absorb shock. In contrast, the iliac surface is covered by fibrocartilage, which is thinner (approximately 0.8 mm) and contributes to joint stability. The SIJ is classified as an amphiarthrosis.

Toxicokinetics

No toxins have been identified that specifically target the SIJ. Many chemicals can induce myopathy with overlap into LBP, although proximal myopathy is more common.

History and Physical

The clinical history of SIJ pain often resembles that of mechanical back pain, with some distinguishing features. Pain is typically localized to the buttock region and may be accompanied by numbness, tingling, weakness, pelvic pain, leg instability, or groin pain. Patients frequently indicate the area between the gluteal folds and posterior iliac crests as the primary site of discomfort.[29] Exacerbating factors include stair climbing, sitting cross-legged, and prolonged sitting or standing. The pain may be stabbing in quality in acute injuries. Many patients report an inability to sleep on the affected side, and symptoms may worsen with menstruation.

Pain radiation is observed in up to 50% of SIJ injuries, most commonly into the lower extremity.[30][31] Referral patterns vary and may involve the posterior thigh, knee, or foot. Pain frequently radiates into the gluteal muscles and may extend to the groin, mimicking hip pathology. The posterior thigh is the most common site of referred pain, reported in 50% of patients with SIJ injury.[32]

The presentation of SIJ injury can overlap with S1 radiculopathy, classically manifesting as sciatica. SIJ-related neuropathic pain involving the S1 nerve root may produce numbness, tingling, or burning pain along the posterior leg, extending below the knee to the plantar aspect of the foot. Depending on the nerve root involved, patients may also experience sensory disturbances or muscle weakness.

The physical examination for suspected SIJ injury requires a comprehensive musculoskeletal and neurologic evaluation of the lumbar spine and bilateral lower extremities. Neurologic and musculoskeletal findings in the lower extremities are typically normal, with preserved muscle strength, sensation, and deep tendon reflexes. Pelvic asymmetry may be evident on inspection, and lower extremity range-of-motion testing is essential for assessing SIJ dysfunction. A rectal examination may be indicated in select cases. Palpation may elicit tenderness over the pelvic floor muscles or along the sacral dimple, corresponding to the long dorsal sacroiliac ligament.[33]

Studies of SIJ mobility and pelvic symmetry have demonstrated poor reliability for diagnosing SIJ dysfunction. However, compression of the iliac crest on the symptomatic side may reproduce pain, whereas reduced pain with pelvic compression suggests a source other than lumbar pathology and supports an SIJ origin.[34][35][36] In cases of SIJ-related neuropathy, loss of the S1 deep tendon reflex, diminished sensation in the S1 dermatome, and weakness in knee extension or flexion may be observed in more advanced presentations.

Special tests are frequently employed in the evaluation of suspected SIJ injury. The Gaenslen test isolates the SIJ by placing the patient supine with one hip flexed to the chest while the examiner applies anterior force to the flexed knee. Simultaneously, the contralateral leg is extended and allowed to fall off the table. Both SIJs are stressed in this position, and reproduction of the patient’s symptoms indicates a positive result.[37] The supine hip posterior thrust test is another commonly used maneuver, entailing downward pressure applied along the axis of the femur to stress the SIJ.

Additional assessments include the Trendelenburg test, which identifies gluteus medius weakness that may contribute to SIJ pain, and the FABER (flexion, abduction, and external rotation) test, where pain localized over the contralateral SIJ constitutes a positive finding. No single maneuver is diagnostic, but the combined use of provocative tests improves accuracy. When 3 or more provocation tests yield positive findings, sensitivity and specificity for SIJ pathology reach 91% and 78%, respectively. Specificity increases to 87% in patients who do not report midline LBP.[38][39]

A thorough history should include intravenous drug use, immunosuppression, recent needle insertion, SIJ therapeutic injection, acupuncture, recent systemic infection, travel, dietary exposures such as undercooked food, and contact with animals that may harbor pathogens (eg, turtles or birds carrying Salmonella). Clinical evaluation should also address fever, warmth, erythema, and swelling over the SIJ. Although not directly related to SIJ pathology, a pilonidal cyst can present with nearby pain and must be differentiated from SIJ infection or SIJ-mediated pain.

Infectious disease exposure history is particularly relevant to the etiology of SIJ infection, especially in pediatric populations where presentations are variable. Features such as fever, localized pain, and impaired ambulation should prompt a comprehensive evaluation with physical examination, laboratory testing, and imaging.

Evaluation

Following the history and physical examination, plain radiography is often the first diagnostic study in suspected SIJ injury, but interpretation has many pitfalls and idiosyncrasies.[40] Weight-bearing anteroposterior views are generally sufficient for the initial evaluation of SIJ-related pain.[41][42] Additional projections, including inlet and outlet views, may be obtained when greater detail is required. Sacroiliac views with 25° to 30° rotation may be considered in cases where initial radiographs are nondiagnostic.

The normal SIJ space measures 4 to 5 mm. Abnormal findings on radiography may include joint space narrowing, sclerotic changes, or erosive alterations. However, interpretation can be unreliable. Early changes of sacroiliitis, particularly grade 1 or 2 radiographic findings, demonstrate high variability, and normal radiographs may still be interpreted as SIJ dysfunction.[43][44] Approximately 20% to 30% of patients with seronegative spondyloarthropathy show abnormalities on plain films.[45][46]

MRI is the most sensitive modality for the assessment of SIJ injury and is critical for the diagnosis of sacroiliitis.[47] Despite its diagnostic value, this imaging method has a significant false-positive rate in otherwise healthy individuals.[48] MRI is usually performed without contrast.[49] Findings associated with sacroiliitis, such as bone marrow edema, are seen in more than 20% of patients with mechanical back pain on MRI.[50][51][52] Similarly, structural changes such as joint erosions may reflect multiple underlying pathologies.[53][54] Scintigraphy may be employed when MRI findings are nondiagnostic.

Computed tomography (CT) is used when MRI is contraindicated or unavailable. CT of the pelvis with contrast may also evaluate vascular and urogenital etiologies. This imaging modality is more sensitive than radiographs but remains inferior to MRI for detecting SIJ injury. CT is not generally recommended to establish the diagnosis of sacroiliitis unless MRI is contraindicated.[55] A low-radiation protocol is considered sufficient when CT is utilized.

Local anesthetic blocks provide a more invasive diagnostic option when SIJ pathology is uncertain. Ultrasound- or fluoroscopy-guided injections allow direct assessment of pain before and after the procedure, determining whether short-acting anesthetics alleviate symptoms. A 75% or greater reduction in pain is often considered indicative of SIJ-mediated pain and may qualify the patient for RFA. Conversely, absent or minimal relief is diagnostically meaningful, suggesting that the SIJ is not the primary pain generator and prompting evaluation of alternative causes of LBP. Candidates for ultrasound-guided diagnostic injections include patients with isolated SIJ pain or pain that is reproducible with 3 positive provocative tests.[56][57]

Laboratory testing forms an important component of the evaluation for a possible inflammatory or infectious etiology. A complete blood count, CRP, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) are commonly obtained when sacroiliitis is identified on pelvic radiography. Additional testing, including HLA-B27, autoimmune serologies, and evaluation for inflammatory bowel disease, may be indicated, depending on the clinical context.

Treatment / Management

Treatment strategies for SIJ injury vary considerably depending on etiology. Pregnancy-related SIJ pain often resolves within several months postpartum, whereas traumatic SIJ injury may require urgent surgical stabilization and can result in chronic pain with long-term disability and functional impairment.

In the setting of acute injury, initial management typically includes ice application and NSAIDs, provided no contraindications are identified. Muscle relaxants, such as cyclobenzaprine, may also be used when muscle spasm contributes to SIJ pain.

Chronic inflammatory sacroiliitis is managed within the framework of the underlying rheumatologic or autoimmune disorder. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, including infliximab and etanercept, may be indicated, while disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) protocols are tailored to the primary systemic condition.

The therapeutic value of corticosteroid injections into the periarticular region of the SIJ remains controversial. Periarticular corticosteroid injections may be performed with or without ultrasound guidance in patients with SIJ pain that does not respond to conservative management. In many cases, pain originates from the posterior ligaments, where a simple trigger-point injection may suffice.

Ultrasound-guided SIJ injections demonstrate higher accuracy and efficiency compared to blind techniques. Periarticular corticosteroid injection also provides superior outcomes compared to lidocaine injection alone.[58] However, the number of studies comparing SIJ corticosteroid injection to sham injection remains limited. Fluoroscopically guided injections of the SIJ have shown variable results for both diagnosis and management.[59](A1)

Corticosteroid injections can be therapeutic in chronic SIJ osteoarthritis, although no more than 3 injections are recommended within a year. Cooled radiofrequency neurotomy provides superior pain relief compared to intra-articular SIJ injections. Nevertheless, intra-articular injection is performed first to confirm the diagnosis prior to RFA. The 2 procedures should not be directly compared, as they serve distinct diagnostic and therapeutic purposes.

Radiofrequency denervation is a treatment option for refractory, chronic SIJ pain. The procedure is performed only after 2 successful injections in which a local anesthetic provided effective relief, similar to medial branch blocks and medial branch RFA. Eligibility for SIJ RFA requires both a positive diagnostic block and a lack of sustained benefit from corticosteroid injection. Reported outcomes have been mixed. Evidence suggests a likely short-term reduction in pain following rhizotomy, although the benefit diminishes over time. High-quality randomized controlled trials are limited, and most published studies include small patient cohorts.[60](A1)

RFA has been shown to demonstrate clinically significant pain reduction and functional improvement at 3 to 6 months in patients with SIJ injury.[61] However, evidence is insufficient to establish whether one ablative technique is superior to another for SIJ denervation. Some studies report that RFA may be effective without first performing a diagnostic block.[62] In a trial of 228 patients unresponsive to conservative management, RFA provided statistically significant pain reduction compared to placebo at 3 months, although the improvement was not considered clinically significant.[63](A1)

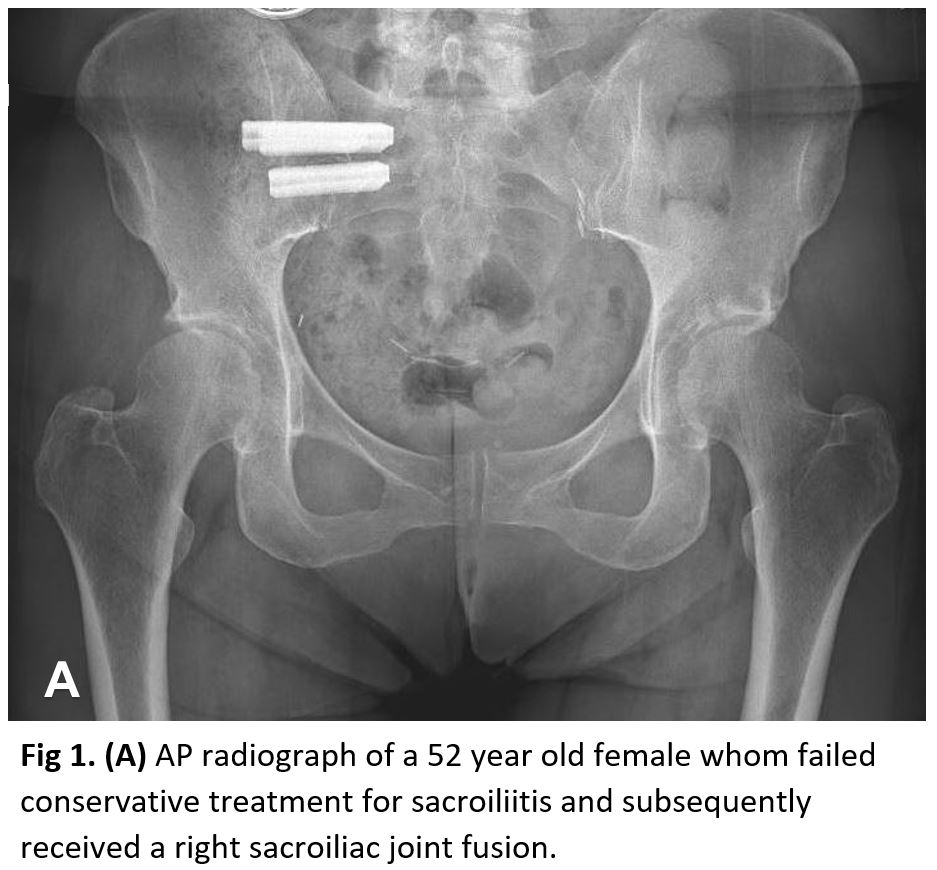

Spinal cord stimulation with leads implanted in the sacrum may reduce chronic, recurrent SIJ pain. When other interventions fail, surgical fusion is an option (see Image. Radiograph of a Right Sacroiliac Joint Fusion). Approximately 80% of patients reported clinically significant pain relief following fusion. Surgical candidacy requires documented pain improvement after a diagnostic injection.

Traditionally, SIJ fusion was performed using an open technique, with the first description published in 1921. Over the past decade, minimally invasive SIJ fusion has become the primary treatment for chronic SIJ dysfunction, with several techniques available. These procedures may be performed through a posterior, posterolateral, or lateral approach.

The techniques are generally categorized as transfixing, intra-articular or interpositional, or spanning. Transfixing devices traverse 2 cortices on one side of the joint, cross the SIJ, and terminate in the opposite bone. Intra-articular procedures involve the placement of implants, such as bone allograft or metallic devices, into the SIJ through a posterior approach. Spanning implants engage both the ilium and sacrum with structural elements that bridge the joint.

A 2023 meta-analysis supports the safety and efficacy of SIJ fusion using transfixing and intra-articular implants when appropriately performed.[64] Substantial literature also supports the overall safety and efficacy of minimally invasive SIJ fusion. Evidence for the lateral approach is considered the strongest, with larger improvements in pain and disability compared to other techniques, although direct comparative studies are lacking.[65] The minimally invasive lateral approach carries a significantly lower risk compared to open procedures. The posterior approach demonstrates efficacy comparable to the lateral approach, with a more favorable risk profile.(A1)

At present, no comparative evidence establishes the clear superiority of one approach over another. The current recommendation is to select the safest technique with the highest likelihood of success.[66][67](B3)

Intra-articular regenerative medicine injections may be considered when conservative measures or corticosteroid injections fail to provide adequate relief in patients seeking to avoid more invasive procedures. The 2 most commonly studied modalities are platelet-rich plasma and bone marrow aspirate concentrate. Current peer-reviewed evidence for regenerative medicine in SIJ-related pain is limited.[68] A consensus report on regenerative medicine concluded that existing data suggest platelet-rich plasma may have efficacy for SIJ-related pain, although further high-quality studies are needed.[69](A1)

Endoscopic denervation of the dorsal rami branches supplying the SIJ has also been explored. A study (n=47) found this technique to be safe, effective, and durable for SIJ dysfunction.[70] Larger comparative trials are required to evaluate its role relative to established treatments.(B2)

Implantable technologies may be considered in severe cases meeting the Chronic Pain Criteria.[71] Spinal cord stimulators require long-term management, including periodic reprogramming and battery replacement every 7 to 10 years. Subarachnoid pain pumps are more complex, as they use custom preservative-free medications prepared by compounding pharmacies. These devices typically require refilling every 90 days, regardless of reservoir volume, due to risks of device malfunction, catheter-related complications, or diversion potential.

Differential Diagnosis

Common causes of SIJ pain include overuse, iatrogenic factors, pregnancy, trauma such as hip fractures, hypermobility, hypomobility, leg length discrepancies, obesity, and prior surgery, particularly lumbar fusion. The differential diagnosis of SIJ-related pain overlaps significantly with that of mechanical LBP, encompassing both vertebral and extravertebral etiologies. Conditions such as synovitis, capsulitis, enthesitis, infection, piriformis syndrome, endometriosis, pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy, bladder pathology, interstitial cystitis, and malignancy (eg, multiple myeloma or metastatic disease) should be considered.[72][73] Functional contributors include scoliosis or leg length discrepancy, while posterior sacral ligament tears may directly produce SIJ pain.

Degenerative and mechanical changes are additional sources of SIJ pain. Progressive osteoarthritis within the SIJ can lead to joint space narrowing, which, in itself, becomes a generator of pain in SIJ dysfunction.

Osteitis condensans ilii warrants specific mention because it is often identified incidentally on plain radiographs of the SIJ. This condition is characterized by sclerosis on the iliac side of the joint, which is typically bilateral, symmetrical, and triangular in distribution. The sclerosis is sharply marginated and dense, occurring primarily in the anterior middle 1/3 of the joint. Absence of sacral involvement or joint space narrowing is considered diagnostic.[74]

Hip osteoarthritis should also be evaluated alongside SIJ osteoarthritis when assessing patients with LBP and pelvic pain.[75] Inflammatory arthropathies remain an important component of the differential diagnosis in SIJ injury, even though they fall outside the scope of this discussion. Reactive arthritis and psoriatic arthritis are examples of inflammatory conditions that can involve the SIJ. Additional contributors include Behçet disease and hyperparathyroidism, both of which may lead to sacroiliitis.[76][77][78] Disc herniation, lumbar spinal stenosis, and mechanical back pain must also be considered in the differential diagnosis of SIJ pain. Infectious causes, while less common, should not be overlooked, particularly in pediatric patients.

Toxicity and Adverse Effect Management

Toxicity and adverse effect management vary depending on the intervention. With conservative therapies for LBP, such as osteopathic manipulation or self-directed SIJ gapping techniques, adverse events are rare apart from falls, which may occur during any therapy session, or complications related to comorbid disease.

Injections carry risks of vascular or neural injury, steroid-related reactions, and procedural pain. Fluoroscopic guidance typically requires the use of a contrast agent, which introduces a potential risk of allergic reaction or renal toxicity, although the injected volume generally remains below 1 to 2 mL. Ultrasound guidance may not reliably detect inadvertent vascular uptake, and blood aspiration is not considered a reliable safeguard.

Bupivacaine has a greater risk of cardiotoxicity than lidocaine when administered intravascularly, a complication best minimized by avoiding the anesthetic in this setting. RFA generally requires only lidocaine, and steroids are not routinely employed. These procedures should only be performed in facilities equipped with a code cart and staffed by personnel trained in Basic (BCLS) and Advanced (ACLS) Cardiac Life Support to manage potential periprocedural complications. Lipid emulsion therapy (lipid rescue) must be immediately available in rare situations where bupivacaine use cannot be avoided.[79] Consequently, bupivacaine has become increasingly avoided in outpatient procedural settings.

All medications carry some degree of toxicity. When opioid therapy is prescribed, a responsible caregiver should be instructed in the administration of intranasal naloxone.

Risks of sacroiliac fusion include bleeding, infection, vascular or visceral injury, and fusion failure. A case report has also described pyogenic sacroiliitis following acupuncture, underscoring the need for vigilance regarding rare but serious complications.[80]

Infectious sacroiliitis carries a risk of systemic complications, including organ damage. Aspiration of the SIJ for culture and sensitivity testing has risks similar to those of therapeutic intra-articular injection. Surgical fusion and debridement depend on the chosen technique. The posterior SIJ approach is generally limited to postoperative pain but carries the same risk of nonunion as other fusion procedures. The anterior approach carries a higher risk of vascular injury, psoas abscess formation, urologic complications, and nerve injury. Thus, anterior procedures are typically restricted to major centers with access to multiple surgical subspecialists for intraoperative support. Custom-compounded corticosteroid preparations designated for single-patient use carry a higher risk of incomplete sterility compared with commercially manufactured depot formulations containing preservatives.[81]

Prognosis

Similar to mechanical back pain, most cases of SIJ injury improve with conservative management. More than 75% of cases respond to conservative measures and physical therapy.[82] Atraumatic SIJ injury is more likely to resolve completely compared with traumatic cases. Sedentary behavior is associated with worse outcomes.[83][84] Physically active patients generally maintain an excellent quality of life despite SIJ injury.[85] Stabilization training has been shown to reduce disability by 50% in the long term.[86] The mean duration of symptoms in chronic SIJ injury is 43 months. In patients with chronic refractory SIJ pain, 2% ultimately require operative fusion. Progression of sacroiliitis-related SIJ deterioration occurs at a rate of 1% to 5% per year.

Complications

The recurrence rate of SIJ injury exceeds 30% in chronic cases.[87][88] Complications include impaired ambulation, chronic pain, disability, and reduced quality of life. As with other musculoskeletal injuries, acute dysfunction should be addressed promptly to prevent transition to chronic pain.

Chronic pain is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality, as well as depression, catastrophic thinking, and opioid dependence. Failure to promptly evaluate and manage sacroiliitis can result in long-term sequelae.

Treatment-related complications vary according to the intervention. Injection and RFA are the most common procedures for SIJ pain. Potential complications include hematoma, contrast-mediated reactions, hyperglycemia from steroid use, and postprocedure infection. Spinal block or spinal headache should not occur even in the least experienced hands. Although rare at the low injection volumes typically used for SIJ procedures, systemic local anesthetic toxicity can develop, particularly with bupivacaine, which predominantly affects cardiac conduction. This complication may be treated with intravenous lipid emulsion therapy (“lipid rescue”).

SIJ pain and injury may become chronic, and patients with persistent symptoms often pursue alternative or experimental treatments, frequently influenced by online information. Some obtain unregulated “magic pain pills” or engage in medical tourism, often at considerable personal expense, for unproven therapies. Although medical tourism may provide access to otherwise unavailable treatments, it also carries risks of exploitation and requires careful evaluation.

Emerging oral and topical agents, including herbal remedies and methylene blue, are under investigation.[89] However, potential drug-herb and drug-chemical interactions must be considered. Many of these products lack regulatory oversight, and labeling may not accurately reflect ingredients or disclose toxic contaminants such as heavy metals.

Basic physical and occupational therapy techniques are generally safe and rarely associated with complications. A gait belt can reduce fall risk. Patients with SIJ pain often have comorbid conditions that necessitate modified physical therapy protocols, such as 1/4 weight bearing in the setting of concomitant fracture. Major medical events, including myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, or cerebrovascular accident, may occur during therapy but are not necessarily attributable to the intervention. In high-risk patients, medical clearance should be obtained and the maximum target heart rate documented before therapy initiation.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Postprocedure instructions vary according to the procedure and the specific protocol of the proceduralist. Most patients are advised to rest at home for the remainder of the day and apply ice as needed. Therapy is generally withheld for 1 day to allow the local anesthetic to wear off and enable the provider to assess the diagnostic value of the intervention. Suture or staple removal may be required in SIJ fusion. Postprocedure wound care typically consists of a dry sterile dressing secured with paper tape.

Patients with chronic mechanical LBP frequently exhibit combined sources of pain, including facet, ligamentous, tendinous, and SIJ involvement, as the condition rarely occurs in isolation. Long-term rehabilitation commonly includes lumbar stabilization and other exercises performed periodically throughout life, even in the absence of symptoms.

Consultations

Virtually any clinician, and certainly any physician, should be able to recognize SIJ-related pain on physical examination. Healthcare providers must also be able to initiate appropriate investigations to exclude other visceral conditions causing similar symptoms.

Training in fluoroscopy-guided, contrast-confirmed, or ultrasound-guided SIJ injection, as well as RFA, is provided across multiple specialties. The most common pathways are through physical medicine and rehabilitation or anesthesiology, although orthopedic surgeons, interventional radiologists, and neurosurgeons also frequently perform these procedures. Sacroplasty for sacral insufficiency fracture, while not technically joint pathology, is also commonly performed by these specialists and is relevant to this discussion.

Rheumatologists may be consulted when an autoimmune disorder is suspected or confirmed. Nutritional and weight management consultations may be appropriate for patients with obesity. Infectious disease specialists may be indicated when an infectious process is suspected or confirmed. Radiologists not only provide imaging support but may also recommend less common modalities such as tagged white blood cell scans or positron emission tomography.

Physical and occupational therapy often overlap, particularly in small community hospitals and rural or underserved regions. Pediatric patients present unique challenges and may require specialized therapists, such as pediatric-trained physical therapists who use play-based approaches. For example, a therapist may encourage a child to blow soap bubbles but pop them only with the great toe, thereby promoting active ankle dorsiflexion. These therapists may also incorporate music or art as therapeutic modalities.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education and deterrence focus on identifying aggravating etiologies, avoiding repetitive stress, maintaining adequate core strength, and modifying activities that irritate the SIJ. Teaching a structured home exercise program is equally important. Exercises should not only target the SIJ but also promote lumbar stabilization, general conditioning, a healthy lifestyle, and an appropriate body mass index.

Patients should understand that the proper use of OTC NSAIDs or acetaminophen can help manage their pain. Other prescription medications may be indicated in chronic cases. In rare cases where opioid therapy is necessary, either periodically or chronically, a responsible household member should be trained in the use of intranasal naloxone. The manufacturer’s training video, which has become the standard, should be reviewed in the physician’s office. The internet link should also be placed in the patient’s chart as evidence of completion. Unless the responsible individual is a medical professional, this training should be repeated annually.

Individuals with autoimmune conditions should be educated on the importance of adhering to DMARD therapy and the need for monitoring adverse effects. In cases of SIJ infection, recurrence is uncommon when antibiotics are administered for an adequate duration. However, recurrence remains possible, particularly in patients who are immunosuppressed, harbor resistant organisms, or have a history of persistent intravenous drug use. These individuals should be counseled to monitor for pain, swelling, fever, chills, night sweats, and other constitutional symptoms as red flags and to seek prompt reevaluation.

Pearls and Other Issues

Clinicians must recognize the SIJ not only as a joint at the terminal spine but also as a site susceptible to underlying pathology, potentially providing diagnostic clues. Healthcare providers should remain current with assessment techniques, evidence-based therapies, and the ethical delivery of care. Strategic management begins with early evaluation and conservative interventions, with escalation based on the underlying diagnosis. Isometric abdominal strengthening (core strengthening) is the primary method of protecting the SIJ.

All clinicians should be able to identify and evaluate red flags in any case of LBP, not solely those involving the SIJ. Important clues include systemic symptoms such as fever or chills, laboratory abnormalities such as elevated ESR or CRP, and examination findings such as weakness or upper motor neuron signs.

The differential diagnosis for SIJ pain, LBP, or thoracic pain is among the broadest in clinical medicine. Clinicians must maintain an open diagnostic perspective. The well-known adages taught in medical training, "When you hear hoofbeats, look for horses, not zebras," and "An uncommon presentation of a common disease is more common than a common presentation of an uncommon disease," are intended not to exclude rare entities but to emphasize that uncommon diseases must remain in the differential.

Approximately 2% of LBP or SIJ pain cases in primary care may have a visceral etiology. In specialist settings, 10% to 25% of patients with back pain are reported to have no vertebral pathology.[90]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Managing SIJ injury can be challenging. LBP secondary to SIJ dysfunction requires an interprofessional team, including a primary care provider, physical therapist, sports medicine specialist, pain medicine physician, radiologist, orthopedic surgeon, nurse specialist, and, in cases of sacroiliitis, a rheumatologist. Without appropriate management, SIJ injury can progress to chronic, debilitating morbidity. Assessment involves multiple steps, including evaluation of the condition and targeted treatment.

Initial history and physical examination should be performed by the primary care provider, encompassing a complete musculoskeletal and neurologic assessment. Radiographs should also be obtained. Most primary care providers may not differentiate SIJ pathology from facet or diskogenic pain, but identification of red flags is essential. Imaging interpretation should be performed by the radiologist. Standard imaging typically includes a weight-bearing anteroposterior view of the SIJ. MRI of the pelvis and sacrum or CT of the pelvis may be indicated based on clinical suspicion and diagnostic need. The primary care provider often directs initial therapy, which may include OTC medications. Treatment typically involves instruction in home exercise programs, use of braces or belts, manipulative therapy, and physical therapy interventions.

In cases of acute, sudden-onset SIJ pain or LBP, patients may present to the emergency department. The primary goal is to rule out immediately life-threatening etiologies, particularly when no inciting event is identified. The concept of “anginal equivalency” has been discussed in pain management literature. These patients are commonly screened for conditions such as cardiac ischemia, renal calculi, urinary tract infection, or ectopic pregnancy. Mechanical LBP is generally a diagnosis of exclusion, with referral to orthopedic or pain management clinics depending on the resources available within the hospital or affiliated healthcare system.

The physical therapist should maintain a low threshold to contact the prescribing practitioner in cases of regression, new-onset weakness or sensory deficit, loss of bowel or bladder control, or any unexplained progression of pain. The therapist may also require a prescription for durable medical equipment, such as an SIJ belt, or for dexamethasone for use in iontophoresis or phonophoresis.

Corticosteroid or anesthetic injections may be performed under either ultrasound or fluoroscopic guidance. Interventional pain management physicians have multiple scopes of practice for these procedures. Refractory treatment, such as RFA of the SIJ following a successful diagnostic block, may also be performed by interventional pain management physicians. This procedure requires a facility equipped with a radiofrequency lesion generator. Referral may be necessary if the initial physician’s office does not have the required equipment. In some cases, the physician performing the initial steroid or anesthetic injection may need to transfer the patient to a hospital or ambulatory surgery center that has a radiofrequency generator.

Suspected inflammatory SIJ injury usually requires further assessment, including laboratory evaluation, and may necessitate management by a rheumatologist. Surgical intervention for debridement or fusion in cases such as an open-book fracture may involve collaboration among general surgeons and, potentially, urologists, in addition to neurosurgeons or orthopedic surgeons for anterior fusion approaches.

In athletes, a sports medicine specialist or therapist may assess sport-specific technique to determine whether biomechanical factors contribute to SIJ pain. This evaluation is ideally conducted in conjunction with a coach for organized teams, such as high school sports. In informal sports settings, such as recreational leagues without a formal coach, other players or a team captain may assist, and a simple video recorded on a phone may be reviewed to evaluate technique.

The management of SIJ pain can address both acute and chronic presentations. Treatment options range from conservative therapy to surgical intervention. However, most cases improve with conservative measures. Effective management often requires the coordinated efforts of multiple healthcare providers.

In cases of sacral insufficiency fracture, bone density should be assessed and may require treatment prior to sacroplasty. Weight-bearing therapy, even in a seated position, or bracing may be necessary during this phase. Depending on facility resources, bracing may be provided by an orthotist or administered by physical or occupational therapy staff, subject to durable medical equipment availability, facility policy, and 3rd-party reimbursement guidelines.

Clear communication and coordination among healthcare team members, facilitated through meetings, case reviews, and shared documentation, are essential to align treatment goals and ensure timely interventions. Nurses and physical and occupational therapists play a critical role in monitoring patient progress, managing adverse effects, providing education, advocating for appropriate resources, and notifying the attending physician of any clinical decline.

Healthcare providers must understand that the SIJ is a terminal joint that can sustain damage and may provide insight into underlying disease. Providers must remain current on assessment techniques, evidence-based therapies, and ethical care delivery. Strategic management should begin with early evaluation and conservative interventions, escalating treatment according to the underlying diagnosis. Pharmacists play a key role in ensuring medication safety and monitoring for potential drug interactions, particularly in patients receiving autoimmune DMARD therapy or intravenous antibiotics.

Consistent follow-up across care settings is essential. Special attention should be given to medication reconciliation, as patients may use unreported OTC or herbal remedies that could interact with prescribed treatments. Vulnerable populations, especially older adults or those with cognitive impairment, may encounter misleading online information, potentially reducing transparency with healthcare providers or caregivers.

Strengthening clinical skills, fostering effective communication, and coordinating care allow healthcare teams to improve outcomes, enhance patient safety, and provide ethical, evidence-based management of chronic SIJ-related pain. This collaborative approach builds patient trust, minimizes care fragmentation, and supports long-term adherence to treatment plans.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Radiograph of a Right Sacroiliac Joint Fusion. This anteroposterior radiograph displays the pelvic region of a 52-year-old female. The image shows the outcome of a right sacroiliac joint fusion, a surgical procedure performed after conservative treatments for sacroiliitis were unsuccessful. Surgical hardware used for stabilization is visible in the right sacroiliac joint region.

Contributed by StatPearls

References

Cocconi F, Maffulli N, Bell A, Memminger MK, Simeone F, Migliorini F. Sacroiliac joint pain: what treatment and when. Expert review of neurotherapeutics. 2024 Nov:24(11):1055-1062. doi: 10.1080/14737175.2024.2400682. Epub 2024 Sep 11 [PubMed PMID: 39262128]

Cohen SP, Chen Y, Neufeld NJ. Sacroiliac joint pain: a comprehensive review of epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Expert review of neurotherapeutics. 2013 Jan:13(1):99-116. doi: 10.1586/ern.12.148. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23253394]

van der Wurff P, Meyne W, Hagmeijer RH. Clinical tests of the sacroiliac joint. Manual therapy. 2000 May:5(2):89-96 [PubMed PMID: 10903584]

Hansen H, Manchikanti L, Simopoulos TT, Christo PJ, Gupta S, Smith HS, Hameed H, Cohen SP. A systematic evaluation of the therapeutic effectiveness of sacroiliac joint interventions. Pain physician. 2012 May-Jun:15(3):E247-78 [PubMed PMID: 22622913]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKuckelman I, Farid AR, Hauth L, Franco H, Mosiman S, Flynn JM, Kocher MS, Noonan KJ. When the Sacroiliac Joint is the Culprit: A Multicenter Investigation of an Uncommon Primary Location for Pediatric Musculoskeletal Infections. Journal of the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America. 2024 Aug:8():100077. doi: 10.1016/j.jposna.2024.100077. Epub 2024 Jul 4 [PubMed PMID: 40433005]

Schmidt GL, Bhandutia AK, Altman DT. Management of Sacroiliac Joint Pain. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2018 Sep 1:26(17):610-616. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-15-00063. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30059395]

Buchanan BK, Varacallo MA. Sacroiliitis. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28846269]

Bina RW, Hurlbert RJ. Sacroiliac Fusion: Another "Magic Bullet" Destined for Disrepute. Neurosurgery clinics of North America. 2017 Jul:28(3):313-320. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2017.02.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28600005]

Weiner DK, Sakamoto S, Perera S, Breuer P. Chronic low back pain in older adults: prevalence, reliability, and validity of physical examination findings. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2006 Jan:54(1):11-20 [PubMed PMID: 16420193]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePolsunas PJ, Sowa G, Fritz JM, Gentili A, Morone NE, Raja SN, Rodriguez E, Schmader K, Scholten JD, Weiner DK. Deconstructing Chronic Low Back Pain in the Older Adult-Step by Step Evidence and Expert-Based Recommendations for Evaluation and Treatment: Part X: Sacroiliac Joint Syndrome. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.). 2016 Sep:17(9):1638-47. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnw151. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27605679]

Ogunseinde B. Single Incision Posteromedial to Ventrolateral (PML) Surgical Technique for Minimally Invasive Sacroiliac Joint Fusion. Clinical spine surgery. 2025 Aug 1:38(7):319-325. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0000000000001867. Epub 2025 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 40539626]

Bjelland EK, Stuge B, Vangen S, Stray-Pedersen B, Eberhard-Gran M. Mode of delivery and persistence of pelvic girdle syndrome 6 months postpartum. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2013 Apr:208(4):298.e1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.12.002. Epub 2012 Dec 5 [PubMed PMID: 23220506]

Coccolini F, Stahel PF, Montori G, Biffl W, Horer TM, Catena F, Kluger Y, Moore EE, Peitzman AB, Ivatury R, Coimbra R, Fraga GP, Pereira B, Rizoli S, Kirkpatrick A, Leppaniemi A, Manfredi R, Magnone S, Chiara O, Solaini L, Ceresoli M, Allievi N, Arvieux C, Velmahos G, Balogh Z, Naidoo N, Weber D, Abu-Zidan F, Sartelli M, Ansaloni L. Pelvic trauma: WSES classification and guidelines. World journal of emergency surgery : WJES. 2017:12():5. doi: 10.1186/s13017-017-0117-6. Epub 2017 Jan 18 [PubMed PMID: 28115984]

Albert HB, Godskesen M, Westergaard JG. Incidence of four syndromes of pregnancy-related pelvic joint pain. Spine. 2002 Dec 15:27(24):2831-4 [PubMed PMID: 12486356]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFiani B, Sekhon M, Doan T, Bowers B, Covarrubias C, Barthelmass M, De Stefano F, Kondilis A. Sacroiliac Joint and Pelvic Dysfunction Due to Symphysiolysis in Postpartum Women. Cureus. 2021 Oct:13(10):e18619. doi: 10.7759/cureus.18619. Epub 2021 Oct 9 [PubMed PMID: 34786225]

Robinson HS, Mengshoel AM, Bjelland EK, Vøllestad NK. Pelvic girdle pain, clinical tests and disability in late pregnancy. Manual therapy. 2010 Jun:15(3):280-5. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2010.01.006. Epub 2010 Feb 8 [PubMed PMID: 20117040]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSnow RE, Neubert AG. Peripartum pubic symphysis separation: a case series and review of the literature. Obstetrical & gynecological survey. 1997 Jul:52(7):438-43 [PubMed PMID: 9219278]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBjelland EK, Eskild A, Johansen R, Eberhard-Gran M. Pelvic girdle pain in pregnancy: the impact of parity. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2010 Aug:203(2):146.e1-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.03.040. Epub 2010 May 26 [PubMed PMID: 20510180]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBjelland EK, Eberhard-Gran M, Nielsen CS, Eskild A. Age at menarche and pelvic girdle syndrome in pregnancy: a population study of 74 973 women. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2011 Dec:118(13):1646-52. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03099.x. Epub 2011 Sep 6 [PubMed PMID: 21895953]

Croisier JL. Factors associated with recurrent hamstring injuries. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.). 2004:34(10):681-95 [PubMed PMID: 15335244]

Omar A, Sari I, Bedaiwi M, Salonen D, Haroon N, Inman RD. Analysis of dedicated sacroiliac views to improve reliability of conventional pelvic radiographs. Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 2017 Oct 1:56(10):1740-1745. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex240. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28957558]

van den Berg R, Lenczner G, Feydy A, van der Heijde D, Reijnierse M, Saraux A, Rahmouni A, Dougados M, Claudepierre P. Agreement between clinical practice and trained central reading in reading of sacroiliac joints on plain pelvic radiographs. Results from the DESIR cohort. Arthritis & rheumatology (Hoboken, N.J.). 2014 Sep:66(9):2403-11. doi: 10.1002/art.38738. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24909765]

Dreyfuss P, Dryer S, Griffin J, Hoffman J, Walsh N. Positive sacroiliac screening tests in asymptomatic adults. Spine. 1994 May 15:19(10):1138-43 [PubMed PMID: 8059269]

Vladimirova N, Møller J, Attauabi M, Madsen G, Seidelin J, Terslev L, Gosvig KK, Siebner HR, Hansen SB, Fana V, Wiell C, Bendtsen F, Burisch J, Østergaard M. Spine and Sacroiliac Joint Involvement in Newly Diagnosed Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Clinical and MRI Findings From a Population-Based Cohort. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2025 Jan 1:120(1):225-240. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000003039. Epub 2024 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 39162769]

Polly DW, Cher DJ, Wine KD, Whang PG, Frank CJ, Harvey CF, Lockstadt H, Glaser JA, Limoni RP, Sembrano JN, INSITE Study Group. Randomized Controlled Trial of Minimally Invasive Sacroiliac Joint Fusion Using Triangular Titanium Implants vs Nonsurgical Management for Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction: 12-Month Outcomes. Neurosurgery. 2015 Nov:77(5):674-90; discussion 690-1. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000988. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26291338]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePolly DW, Swofford J, Whang PG, Frank CJ, Glaser JA, Limoni RP, Cher DJ, Wine KD, Sembrano JN, INSITE Study Group. Two-Year Outcomes from a Randomized Controlled Trial of Minimally Invasive Sacroiliac Joint Fusion vs. Non-Surgical Management for Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction. International journal of spine surgery. 2016:10():28. doi: 10.14444/3028. Epub 2016 Aug 23 [PubMed PMID: 27652199]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGomez-Sierra MA, Martinez-Rondanelli A, Palacio L, Martinez-Cano JP. Traumatic Anterior Hip Dislocation With an Open Book Pelvic Fracture and Femoral Artery Compression: An Atypical Case Report. JBJS case connector. 2024 Oct 1:14(4):. doi: e24.00177. Epub 2024 Dec 12 [PubMed PMID: 39666833]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceUlas ST, Diekhoff T, Ziegeler K. Sex Disparities of the Sacroiliac Joint: Focus on Joint Anatomy and Imaging Appearance. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). 2023 Feb 9:13(4):. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics13040642. Epub 2023 Feb 9 [PubMed PMID: 36832130]

Vleeming A, Albert HB, Ostgaard HC, Sturesson B, Stuge B. European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2008 Jun:17(6):794-819. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0602-4. Epub 2008 Feb 8 [PubMed PMID: 18259783]

Protopopov M, Poddubnyy D. Radiographic progression in non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Expert review of clinical immunology. 2018 Jun:14(6):525-533. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2018.1477591. Epub 2018 May 24 [PubMed PMID: 29774755]

Ziade NR. HLA B27 antigen in Middle Eastern and Arab countries: systematic review of the strength of association with axial spondyloarthritis and methodological gaps. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2017 Jun 29:18(1):280. doi: 10.1186/s12891-017-1639-5. Epub 2017 Jun 29 [PubMed PMID: 28662723]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceThawrani DP, Agabegi SS, Asghar F. Diagnosing Sacroiliac Joint Pain. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2019 Feb 1:27(3):85-93. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-17-00132. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30278010]

Fitzgerald CM, Neville CE, Mallinson T, Badillo SA, Hynes CK, Tu FF. Pelvic floor muscle examination in female chronic pelvic pain. The Journal of reproductive medicine. 2011 Mar-Apr:56(3-4):117-22 [PubMed PMID: 21542528]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePotter NA, Rothstein JM. Intertester reliability for selected clinical tests of the sacroiliac joint. Physical therapy. 1985 Nov:65(11):1671-5 [PubMed PMID: 2932746]

Slipman CW, Sterenfeld EB, Chou LH, Herzog R, Vresilovic E. The predictive value of provocative sacroiliac joint stress maneuvers in the diagnosis of sacroiliac joint syndrome. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 1998 Mar:79(3):288-92 [PubMed PMID: 9523780]

Levangie PK. Four clinical tests of sacroiliac joint dysfunction: the association of test results with innominate torsion among patients with and without low back pain. Physical therapy. 1999 Nov:79(11):1043-57 [PubMed PMID: 10534797]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLaslett M. Evidence-based diagnosis and treatment of the painful sacroiliac joint. The Journal of manual & manipulative therapy. 2008:16(3):142-52 [PubMed PMID: 19119403]

Rashbaum RF, Ohnmeiss DD, Lindley EM, Kitchel SH, Patel VV. Sacroiliac Joint Pain and Its Treatment. Clinical spine surgery. 2016 Mar:29(2):42-8. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0000000000000359. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26889985]

Buchanan P, Vodapally S, Lee DW, Hagedorn JM, Bovinet C, Strand N, Sayed D, Deer T. Successful Diagnosis of Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction. Journal of pain research. 2021:14():3135-3143. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S327351. Epub 2021 Oct 8 [PubMed PMID: 34675642]

Carotti M, Ceccarelli L, Poliseno AC, Ribichini F, Bandinelli F, Scarano E, Farah S, Di Carlo M, Giovagnoni A, Salaffi F. Imaging of Sacroiliac Pain: The Current State-of-the-Art. Journal of personalized medicine. 2024 Aug 17:14(8):. doi: 10.3390/jpm14080873. Epub 2024 Aug 17 [PubMed PMID: 39202065]

Miller R, Beck NA, Sampson NR, Zhu X, Flynn JM, Drummond D. Imaging modalities for low back pain in children: a review of spondyloysis and undiagnosed mechanical back pain. Journal of pediatric orthopedics. 2013 Apr-May:33(3):282-8. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e318287fffb. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23482264]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRodriguez DP, Poussaint TY. Imaging of back pain in children. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2010 May:31(5):787-802. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1832. Epub 2009 Nov 19 [PubMed PMID: 19926701]

Diekhoff T, Hermann KG, Greese J, Schwenke C, Poddubnyy D, Hamm B, Sieper J. Comparison of MRI with radiography for detecting structural lesions of the sacroiliac joint using CT as standard of reference: results from the SIMACT study. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2017 Sep:76(9):1502-1508. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210640. Epub 2017 Mar 10 [PubMed PMID: 28283515]

van Tubergen A, Heuft-Dorenbosch L, Schulpen G, Landewé R, Wijers R, van der Heijde D, van Engelshoven J, van der Linden S. Radiographic assessment of sacroiliitis by radiologists and rheumatologists: does training improve quality? Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2003 Jun:62(6):519-25 [PubMed PMID: 12759287]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJang JH, Ward MM, Rucker AN, Reveille JD, Davis JC Jr, Weisman MH, Learch TJ. Ankylosing spondylitis: patterns of radiographic involvement--a re-examination of accepted principles in a cohort of 769 patients. Radiology. 2011 Jan:258(1):192-8. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100426. Epub 2010 Oct 22 [PubMed PMID: 20971774]

Poddubnyy D, Brandt H, Vahldiek J, Spiller I, Song IH, Rudwaleit M, Sieper J. The frequency of non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis in relation to symptom duration in patients referred because of chronic back pain: results from the Berlin early spondyloarthritis clinic. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2012 Dec:71(12):1998-2001. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201945. Epub 2012 Aug 21 [PubMed PMID: 22915622]

Khmelinskii N, Regel A, Baraliakos X. The Role of Imaging in Diagnosing Axial Spondyloarthritis. Frontiers in medicine. 2018:5():106. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00106. Epub 2018 Apr 17 [PubMed PMID: 29719835]

Weber U, Jurik AG, Lambert RG, Maksymowych WP. Imaging in Spondyloarthritis: Controversies in Recognition of Early Disease. Current rheumatology reports. 2016 Sep:18(9):58. doi: 10.1007/s11926-016-0607-7. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27435070]

Lambert RG, Bakker PA, van der Heijde D, Weber U, Rudwaleit M, Hermann KG, Sieper J, Baraliakos X, Bennett A, Braun J, Burgos-Vargas R, Dougados M, Pedersen SJ, Jurik AG, Maksymowych WP, Marzo-Ortega H, Østergaard M, Poddubnyy D, Reijnierse M, van den Bosch F, van der Horst-Bruinsma I, Landewé R. Defining active sacroiliitis on MRI for classification of axial spondyloarthritis: update by the ASAS MRI working group. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2016 Nov:75(11):1958-1963. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208642. Epub 2016 Jan 14 [PubMed PMID: 26768408]

Marzo-Ortega H, McGonagle D, O'Connor P, Hensor EM, Bennett AN, Green MJ, Emery P. Baseline and 1-year magnetic resonance imaging of the sacroiliac joint and lumbar spine in very early inflammatory back pain. Relationship between symptoms, HLA-B27 and disease extent and persistence. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2009 Nov:68(11):1721-7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.097931. Epub 2008 Nov 19 [PubMed PMID: 19019894]

Weber U, Lambert RG, Østergaard M, Hodler J, Pedersen SJ, Maksymowych WP. The diagnostic utility of magnetic resonance imaging in spondylarthritis: an international multicenter evaluation of one hundred eighty-seven subjects. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2010 Oct:62(10):3048-58. doi: 10.1002/art.27571. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20496416]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceArnbak B, Grethe Jurik A, Hørslev-Petersen K, Hendricks O, Hermansen LT, Loft AG, Østergaard M, Pedersen SJ, Zejden A, Egund N, Holst R, Manniche C, Jensen TS. Associations Between Spondyloarthritis Features and Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of 1,020 Patients With Persistent Low Back Pain. Arthritis & rheumatology (Hoboken, N.J.). 2016 Apr:68(4):892-900. doi: 10.1002/art.39551. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26681230]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencede Hooge M, van den Berg R, Navarro-Compán V, Reijnierse M, van Gaalen F, Fagerli K, Landewé R, van Oosterhout M, Ramonda R, Huizinga T, van der Heijde D. Patients with chronic back pain of short duration from the SPACE cohort: which MRI structural lesions in the sacroiliac joints and inflammatory and structural lesions in the spine are most specific for axial spondyloarthritis? Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2016 Jul:75(7):1308-14. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207823. Epub 2015 Aug 18 [PubMed PMID: 26286018]

Weber U, Pedersen SJ, Østergaard M, Rufibach K, Lambert RG, Maksymowych WP. Can erosions on MRI of the sacroiliac joints be reliably detected in patients with ankylosing spondylitis? - A cross-sectional study. Arthritis research & therapy. 2012 May 24:14(3):R124. doi: 10.1186/ar3854. Epub 2012 May 24 [PubMed PMID: 22626458]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMandl P, Navarro-Compán V, Terslev L, Aegerter P, van der Heijde D, D'Agostino MA, Baraliakos X, Pedersen SJ, Jurik AG, Naredo E, Schueller-Weidekamm C, Weber U, Wick MC, Bakker PA, Filippucci E, Conaghan PG, Rudwaleit M, Schett G, Sieper J, Tarp S, Marzo-Ortega H, Østergaard M, European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR). EULAR recommendations for the use of imaging in the diagnosis and management of spondyloarthritis in clinical practice. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2015 Jul:74(7):1327-39. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206971. Epub 2015 Apr 2 [PubMed PMID: 25837448]

Young S, Aprill C, Laslett M. Correlation of clinical examination characteristics with three sources of chronic low back pain. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2003 Nov-Dec:3(6):460-5 [PubMed PMID: 14609690]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRupert MP, Lee M, Manchikanti L, Datta S, Cohen SP. Evaluation of sacroiliac joint interventions: a systematic appraisal of the literature. Pain physician. 2009 Mar-Apr:12(2):399-418 [PubMed PMID: 19305487]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLuukkainen RK, Wennerstrand PV, Kautiainen HH, Sanila MT, Asikainen EL. Efficacy of periarticular corticosteroid treatment of the sacroiliac joint in non-spondylarthropathic patients with chronic low back pain in the region of the sacroiliac joint. Clinical and experimental rheumatology. 2002 Jan-Feb:20(1):52-4 [PubMed PMID: 11892709]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceIrwin RW, Watson T, Minick RP, Ambrosius WT. Age, body mass index, and gender differences in sacroiliac joint pathology. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation. 2007 Jan:86(1):37-44 [PubMed PMID: 17304687]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMaas ET, Ostelo RW, Niemisto L, Jousimaa J, Hurri H, Malmivaara A, van Tulder MW. Radiofrequency denervation for chronic low back pain. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2015 Oct 23:2015(10):CD008572. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008572.pub2. Epub 2015 Oct 23 [PubMed PMID: 26495910]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCohen SP, Hurley RW, Buckenmaier CC 3rd, Kurihara C, Morlando B, Dragovich A. Randomized placebo-controlled study evaluating lateral branch radiofrequency denervation for sacroiliac joint pain. Anesthesiology. 2008 Aug:109(2):279-88. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31817f4c7c. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18648237]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCohen SP, Williams KA, Kurihara C, Nguyen C, Shields C, Kim P, Griffith SR, Larkin TM, Crooks M, Williams N, Morlando B, Strassels SA. Multicenter, randomized, comparative cost-effectiveness study comparing 0, 1, and 2 diagnostic medial branch (facet joint nerve) block treatment paradigms before lumbar facet radiofrequency denervation. Anesthesiology. 2010 Aug:113(2):395-405. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181e33ae5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20613471]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceJuch JNS, Maas ET, Ostelo RWJG, Groeneweg JG, Kallewaard JW, Koes BW, Verhagen AP, van Dongen JM, Huygen FJPM, van Tulder MW. Effect of Radiofrequency Denervation on Pain Intensity Among Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain: The Mint Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA. 2017 Jul 4:318(1):68-81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7918. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28672319]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceJung MW. Safety and Preliminary Effectiveness of Lateral Transiliac Sacroiliac Joint Fusion by Interventional Pain Physicians: A Retrospective Analysis. Journal of pain research. 2024:17():2147-2153. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S462072. Epub 2024 Jun 17 [PubMed PMID: 38910592]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWhang PG, Patel V, Duhon B, Sturesson B, Cher D, Carlton Reckling W, Capobianco R, Polly D. Minimally Invasive SI Joint Fusion Procedures for Chronic SI Joint Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Safety and Efficacy. International journal of spine surgery. 2023 Dec 26:17(6):794-808. doi: 10.14444/8543. Epub 2023 Dec 26 [PubMed PMID: 37798076]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSayed D, Deer TR, Tieppo Francio V, Lam CM, Sochacki K, Hussain N, Weaver TE, Karri J, Orhurhu V, Strand NH, Weisbein JS, Hagedorn JM, D'Souza RS, Budwany RR, Chitneni A, Amirdelfan K, Dorsi MJ, Nguyen DTD, Bovinet C, Abd-Elsayed A. American Society of Pain and Neuroscience Best Practice (ASPN) Guideline for the Treatment of Sacroiliac Disorders [Response to Letter]. Journal of pain research. 2024:17():2509-2510. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S482580. Epub 2024 Jul 29 [PubMed PMID: 39100138]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCalodney A, Azeem N, Buchanan P, Skaribas I, Antony A, Kim C, Girardi G, Vu C, Bovinet C, Vogel R, Li S, Jassal N, Josephson Y, Lubenow T, Lam CM, Deer TR. Safety, Efficacy, and Durability of Outcomes: Results from SECURE: A Single Arm, Multicenter, Prospective, Clinical Study on a Minimally Invasive Posterior Sacroiliac Fusion Allograft Implant. Journal of pain research. 2024:17():1209-1222. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S458334. Epub 2024 Mar 20 [PubMed PMID: 38524688]

Navani A, Manchikanti L, Albers SL, Latchaw RE, Sanapati J, Kaye AD, Atluri S, Jordan S, Gupta A, Cedeno D, Vallejo A, Fellows B, Knezevic NN, Pappolla M, Diwan S, Trescot AM, Soin A, Kaye AM, Aydin SM, Calodney AK, Candido KD, Bakshi S, Benyamin RM, Vallejo R, Watanabe A, Beall D, Stitik TP, Foye PM, Helander EM, Hirsch JA. Responsible, Safe, and Effective Use of Biologics in the Management of Low Back Pain: American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) Guidelines. Pain physician. 2019 Jan:22(1S):S1-S74 [PubMed PMID: 30717500]

D'Souza RS, Her YF, Hussain N, Karri J, Schatman ME, Calodney AK, Lam C, Buchheit T, Boettcher BJ, Chang Chien GC, Pritzlaff SG, Centeno C, Shapiro SA, Klasova J, Grider JS, Hubbard R, Ege E, Johnson S, Epstein MH, Kubrova E, Ramadan ME, Moreira AM, Vardhan S, Eshraghi Y, Javed S, Abdullah NM, Christo PJ, Diwan S, Hassett LC, Sayed D, Deer TR. Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines on Regenerative Medicine Treatment for Chronic Pain: A Consensus Report from a Multispecialty Working Group. Journal of pain research. 2024:17():2951-3001. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S480559. Epub 2024 Sep 11 [PubMed PMID: 39282657]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHasan S, Halalmeh DR, Ansari YZ, Herrera A, Hofstetter CP. Full-Endoscopic Sacroiliac Joint Denervation for Painful Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction: A Prospective 2-Year Clinical Outcomes and Predictors for Improved Outcomes. Neurosurgery. 2025 Jan 1:96(1):213-222. doi: 10.1227/neu.0000000000003053. Epub 2024 Jun 25 [PubMed PMID: 38916375]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceStretanski MF, Kopitnik NL, Matha A, Conermann T. Chronic Pain. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31971706]

Kocak O, Kocak AY, Sanal B, Kulan G. Bilateral Sacroiliitis Confirmed with Magnetic Resonance Imaging during Isotretinoin Treatment: Assessment of 11 Patients and a Review of the Literature. Acta dermatovenerologica Croatica : ADC. 2017 Oct:25(3):228-233 [PubMed PMID: 29252176]

Pandita A, Madhuripan N, Hurtado RM, Dhamoon A. Back pain and oedematous Schmorl node: a diagnostic dilemma. BMJ case reports. 2017 May 22:2017():. pii: bcr-2017-219904. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-219904. Epub 2017 May 22 [PubMed PMID: 28536227]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceUslu S. Osteitis condensans ilii: a mimicker of axial spondyloarthritis. Scandinavian journal of rheumatology. 2025 May 8:():1-2. doi: 10.1080/03009742.2025.2495493. Epub 2025 May 8 [PubMed PMID: 40338025]

Poddubnyy D, Listing J, Haibel H, Knüppel S, Rudwaleit M, Sieper J. Functional relevance of radiographic spinal progression in axial spondyloarthritis: results from the GErman SPondyloarthritis Inception Cohort. Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 2018 Apr 1:57(4):703-711. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex475. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29373733]

Slobodin G, Hussein H, Rosner I, Eshed I. Sacroiliitis - early diagnosis is key. Journal of inflammation research. 2018:11():339-344. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S149494. Epub 2018 Sep 10 [PubMed PMID: 30237730]

Chahal BS, Kwan ALC, Dhillon SS, Olubaniyi BO, Jhiangri GS, Neilson MM, Lambert RGW. Radiation Exposure to the Sacroiliac Joint From Low-Dose CT Compared With Radiography. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2018 Nov:211(5):1058-1062. doi: 10.2214/AJR.18.19678. Epub 2018 Sep 12 [PubMed PMID: 30207791]

Gutierrez M, Rodriguez S, Soto-Fajardo C, Santos-Moreno P, Sandoval H, Bertolazzi C, Pineda C. Ultrasound of sacroiliac joints in spondyloarthritis: a systematic review. Rheumatology international. 2018 Oct:38(10):1791-1805. doi: 10.1007/s00296-018-4126-x. Epub 2018 Aug 11 [PubMed PMID: 30099591]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSepulveda EA, Pak A. Lipid Emulsion Therapy. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31751087]

Bayala YLT, Ayouba Tinni I, Kaboré F, Zabsonré/Tiendrebeogo WJS, Ouedraogo DD. Infectious pyogenic sacroiliitis following acupuncture: a series of three cases and review of the literature. Acupuncture in medicine : journal of the British Medical Acupuncture Society. 2025 Apr:43(2):114-119. doi: 10.1177/09645284251327200. Epub 2025 Mar 22 [PubMed PMID: 40119763]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShehab N, Brown MN, Kallen AJ, Perz JF. U.S. Compounding Pharmacy-Related Outbreaks, 2001-2013: Public Health and Patient Safety Lessons Learned. Journal of patient safety. 2018 Sep:14(3):164-173. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000188. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26001553]

Cusi M, Saunders J, Hungerford B, Wisbey-Roth T, Lucas P, Wilson S. The use of prolotherapy in the sacroiliac joint. British journal of sports medicine. 2010 Feb:44(2):100-4. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2007.042044. Epub 2008 Apr 9 [PubMed PMID: 18400878]

Added MAN, de Freitas DG, Kasawara KT, Martin RL, Fukuda TY. STRENGTHENING THE GLUTEUS MAXIMUS IN SUBJECTS WITH SACROILIAC DYSFUNCTION. International journal of sports physical therapy. 2018 Feb:13(1):114-120 [PubMed PMID: 29484248]

Miles D, Bishop M. Use of Manual Therapy for Posterior Pelvic Girdle Pain. PM & R : the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation. 2019 Aug:11 Suppl 1():S93-S97. doi: 10.1002/pmrj.12172. Epub 2019 Jun 26 [PubMed PMID: 31020812]

Nelson AM, Nagpal G. Interventional Approaches to Low Back Pain. Clinical spine surgery. 2018 Jun:31(5):188-196. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0000000000000542. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28486278]

Stuge B, Laerum E, Kirkesola G, Vøllestad N. The efficacy of a treatment program focusing on specific stabilizing exercises for pelvic girdle pain after pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Spine. 2004 Feb 15:29(4):351-9 [PubMed PMID: 15094530]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWhang PG, Darr E, Meyer SC, Kovalsky D, Frank C, Lockstadt H, Limoni R, Redmond AJ, Ploska P, Oh M, Chowdhary A, Cher D, Hillen T. Long-Term Prospective Clinical And Radiographic Outcomes After Minimally Invasive Lateral Transiliac Sacroiliac Joint Fusion Using Triangular Titanium Implants. Medical devices (Auckland, N.Z.). 2019:12():411-422. doi: 10.2147/MDER.S219862. Epub 2019 Sep 26 [PubMed PMID: 31576181]

van Lunteren M, Ez-Zaitouni Z, de Koning A, Dagfinrud H, Ramonda R, Jacobsson L, Landewé R, van der Heijde D, van Gaalen FA. In Early Axial Spondyloarthritis, Increasing Disease Activity Is Associated with Worsening of Health-related Quality of Life over Time. The Journal of rheumatology. 2018 Jun:45(6):779-784. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.170796. Epub 2018 Mar 15 [PubMed PMID: 29545448]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMiralles L, López-Bas R, Díaz-Alejo C, Roldan CJ. Methylene Blue, a Unique Topical Analgesic: A Case Report. Journal of palliative medicine. 2024 Oct:27(10):1425-1428. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2024.0033. Epub 2024 Jul 15 [PubMed PMID: 39007195]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKunow A, Freyer Martins Pereira J, Chenot JF. Extravertebral low back pain: a scoping review. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2024 May 7:25(1):363. doi: 10.1186/s12891-024-07435-9. Epub 2024 May 7 [PubMed PMID: 38714994]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence