Introduction

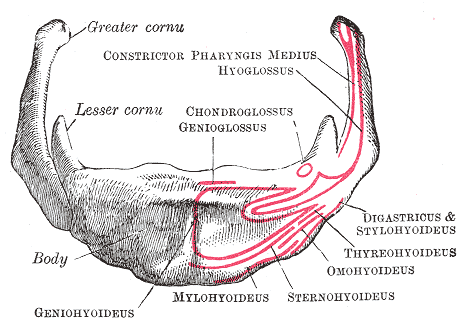

The hyoid bone, or simply hyoid, refers to a small, U- or horseshoe-shaped solitary bone located in the midline of the neck, inferior to the base of the mandible and anterior to the 4th cervical vertebra (see Image. Anterior View of the Hyoid Bone). Positioned just superior to the thyroid cartilage, the hyoid remains unconnected to adjacent bones and instead associates with an extended tendon-muscular complex. Many anatomists and anthropologists consider this bone unconventional for this reason. Anchoring occurs within the anterior triangle of the neck via muscles originating from the larynx, pharynx, tongue, and floor of the mouth. The term "hyoid" comes from the Greek word hyodeides, meaning “shaped like the letter Upsilon.” As part of the hyoid-larynx complex, the hyoid holds clinical and forensic relevance despite its designation as an unconventional bone.[1]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The hyoid consists of a body, 2 greater horns, and 2 lesser horns. The body forms the central, quadrilateral-shaped broad segment. The greater horns extend laterally as the longer and larger components compared to the lesser horns. These horns are also referred to as "cornu majus" and "cornu minus," respectively. The body and greater horns together define the characteristic U-shape, with the greater horns forming the limbs of the "U" on either side of the body. The greater and lesser horns typically unite with the body via fibrous tissue or a true synovial joint.[2] Advancing age often leads to physiological ankylosis at the articulations between the horns and the body.

The hyoid participates in all major functional actions of the orofacial complex. Patency of the airway between the oropharynx and the tracheal rings depends, in part, on the structural position of this bone. By connecting to the larynx, the hyoid also contributes to phonation. Additional roles include tongue movement, mastication, swallowing, prevention of regurgitation, and respiration. Continued stability of the hyoid ensures coordination among these functions.

Embryology

The 2nd pharyngeal arch forms the lesser horn (lesser cornu) and the upper portion of the hyoid body, while the greater horn (greater cornu) and the lower part of the body originate from the 3rd pharyngeal arch. The embryological origin of the hyoid remains a subject of debate. Ossification begins in the greater horns toward the end of the fetal gestational period. The body undergoes ossification shortly after birth, followed by ossification of the lesser horns during the 1st or 2nd postnatal year. In adulthood, fusion of the horns with the body commonly occurs, although not in all individuals. During infancy, the hyoid lies anterior to the 2nd and 3rd cervical vertebrae. In later stages of development, the hyoid descends to the level of the 4th and 5th cervical vertebrae, along with associated structures such as the epiglottis and larynx.[3]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Arterial blood supply to the hyoid bone primarily originates from branches of the external carotid artery. The lingual artery, a major branch, gives rise to the suprahyoid branch, which courses along the superior border of the hyoid, supplying both the bone and the associated musculature. The submental branch of the facial artery also contributes to vascularization of the suprahyoid region, supporting the overlying muscles. Inferiorly, the superior thyroid artery provides the infrahyoid branch, which travels beneath the thyrohyoid muscle and along the lower border of the hyoid, further reinforcing the vascular network in this area.[4][5]

Although not a primary structure for lymphatic drainage, the hyoid lies within a region densely populated by lymphatic vessels and nodes. Surrounding suprahyoid and infrahyoid areas facilitate drainage of the oral cavity, pharynx, and anterior neck.

Nerves

Although not a major site of sensory input, the hyoid bone supports multiple muscles that receive coordinated motor innervation from various cranial and cervical nerves. The mylohyoid nerve, a branch of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V3), innervates the mylohyoid muscle and the anterior belly of the digastric, contributing to elevation of the floor of the mouth. The facial nerve (cranial nerve VII) supplies motor input to the stylohyoid and the posterior belly of the digastric, both of which assist in hyoid elevation and stabilization during swallowing and speech.

The geniohyoid muscle receives innervation from fibers of the 1st cervical spinal nerve, which travel alongside the hypoglossal nerve (cranial nerve XII). In addition, the ansa cervicalis, formed by fibers from the 1st to 3rd cervical spinal nerves, provides motor innervation to several infrahyoid muscles responsible for anchoring and stabilizing the hyoid during functional activity. Although sensory innervation to the hyoid remains limited, the periosteum may receive sympathetic fibers that contribute to nociceptive signaling under pathological conditions such as trauma or infection.[6]

Muscles

The hyoid functions as an anchor for both the suprahyoid and infrahyoid muscles. Suspension from the temporal styloid processes occurs via the stylohyoid ligaments on either side. Inferiorly, ligamentous attachments to the superior aspect of the thyroid cartilage, mediated by the thyrohyoid membrane, restrict downward displacement. Posteriorly, the cervical fascia connects the hyoid to the cervical spine.

Suprahyoid Muscles

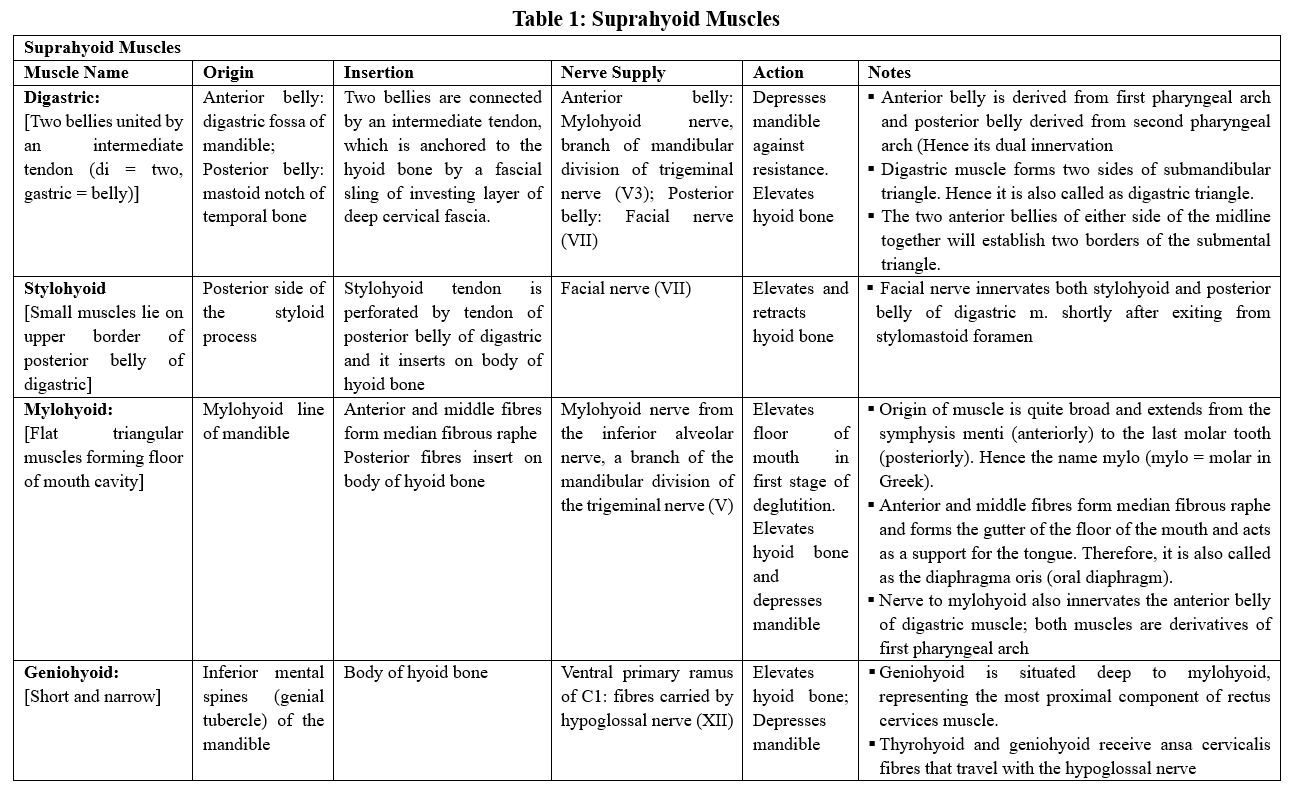

The suprahyoid muscles consist of 4 pairs on either side of the anterior midline, positioned above the level of the hyoid (see Image. Suprahyoid Muscles). Located between 2 bony landmarks—the base of the mandible above and the hyoid below—these muscles include the digastric, stylohyoid, mylohyoid, and geniohyoid.

The digastric muscle has 2 bellies, anterior and posterior. The anterior belly originates from the digastric fossa of the mandible, while the posterior belly originates from the mastoid notch. Both bellies insert into the intermediate tendon, which attaches to the hyoid. The stylohyoid muscle, originating from the temporal styloid process, lies parallel to the posterior belly of the digastric. The mylohyoid muscle arises from the mylohyoid line of the mandible and forms the floor of the mouth, creating a sling beneath the tongue. The geniohyoid muscle, narrow and short, originates from the inferior mental spine of the symphysis menti. The stylohyoid, mylohyoid, and geniohyoid insert on the body of the hyoid.

Functional significance

The primary function of the suprahyoid muscles is to elevate the hyoid bone. When the base of the mandible is stabilized, these muscles elevate the hyoid bone, subsequently elevating the floor of the mouth to facilitate deglutition. When the infrahyoid muscles stabilize the hyoid, the suprahyoid muscles assist in depressing the mandible, enabling a wide mouth opening.

The digastric muscle contributes to mouth opening by depressing and retracting the chin. This muscle also assists deglutition by drawing the floor of the mouth and the hyoid bone upward. The mylohyoid muscle facilitates speaking and deglutition by raising the floor of the mouth and tongue, and, when the hyoid is fixed, it aids in mandibular depression. The stylohyoid muscle helps draw the hyoid bone upward and backward, elevating the tongue and elongating the floor of the mouth. The geniohyoid muscle moves the hyoid bone upward and forward, also helping to widen the airway passage.

Infrahyoid Muscles

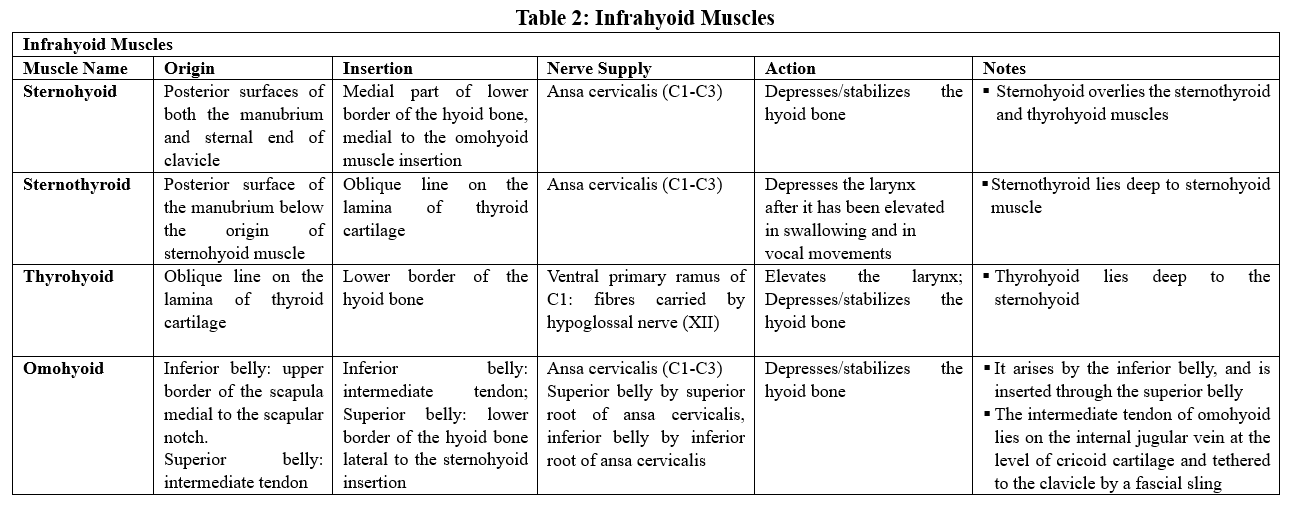

The infrahyoid muscles consist of 4 pairs located in the anterior neck, including the sternohyoid, sternothyroid, omohyoid, and thyrohyoid muscles (see Image. Infrahyoid Muscles). These muscles are positioned between the hyoid above and the shoulder girdle below. The sternohyoid muscle primarily originates from the back of the manubrium and inserts on the medial aspect of the inferior border of the hyoid body. The sternothyroid muscle originates from the back of the manubrium and inserts along the oblique line of the thyroid cartilage.

The omohyoid muscle has superior and inferior bellies. The superior belly arises from the intermediate tendon of the omohyoid and inserts on the hyoid, while the inferior belly originates from the superior border of the scapula and inserts into the intermediate tendon. The thyrohyoid muscle originates from the oblique line of the thyroid cartilage and inserts at the inferior aspect of the hyoid body and the greater cornu.[7]

Functional significance

The primary function of the infrahyoid muscles is to depress the hyoid bone. These muscles play an active role in swallowing by facilitating the movement of the larynx. The thyrohyoid elevates the larynx, while the sternothyroid depresses it. The omohyoid also supports proper venous blood return through its attachment to the carotid sheath. By pulling on the carotid sheath, the omohyoid helps maintain a low-pressure system in the internal jugular vein, enhancing blood return to the superior vena cava.

Other Muscles Related to the Hyoid

The hyoglossus and the middle pharyngeal constrictor both originate from the hyoid. However, these muscles are not classified as part of the primary group of muscles directly associated with the hyoid, as the others above.

Physiologic Variants

The hyoid exhibits a wide range of anatomical variations, likely due to the asymmetry of the greater and lesser horns. Therefore, the hyoid ranks among the most polymorphic parts of the human body. The most common variation occurs during ankylosis of the joints between the greater and lesser horns and the body of the hyoid. Factors such as ethnicity, sex, age, height, and weight contribute to morphological variations, which may occur unilaterally or bilaterally. Multiple variations may also be present in the same individual.

Surprisingly, the absence of the hyoid has been reported in a male neonate with a teratoma, a mandibular cleft, and respiratory distress.[8] These anomalies correlate with conditions such as micrognathia, Pierre Robin sequence, and cleft lip and palate. Symptoms associated with these anomalies include dysphagia, limited neck movement, and a foreign body sensation in the throat.

The levator glandulae thyroideae is considered an accessory muscle, observed infrequently and exhibiting many variations. This muscle originates from the hyoid bone or thyroid cartilage and inserts into the capsule of the thyroid gland. Some authors define this structure as the fibromusculoglandular band.[9][10] Embryological development of infrahyoid muscles plays a significant role in their anatomical variations. Numerous neck muscle variants have been observed in aneuploidies such as Down and Edwards syndromes.[11]

Surgical Considerations

The Hyoid and Its Relation to Blood Vessels

The tip of the greater horn of the hyoid serves as a key landmark for cervical surgery in the midneck region. The carotid bifurcation and the superior thyroid and lingual arteries are closely related to the tip of the greater horn. The tip of the greater horn is a landmark for locating these arteries during cervical surgery. The carotid bifurcation lies inferior and posterior to the tip of the greater horn. The origin of the superior thyroid artery, the 1st branch of the external carotid artery, lies below the level of the greater horn. The lingual artery branches off the external carotid artery above the level of the greater horn.

The Hyoid and Its Relation to Nerves

The hypoglossal and superior laryngeal nerves are closely related to the tip of the greater horn of the hyoid. The tip of the greater horn helps surgeons locate these nerves during cervical surgery. The hypoglossal nerve lies superior to the tip of the greater horn. The superior laryngeal nerve divides into external and internal branches as it passes behind the greater horn, with the external branch lying deeper than the internal one.[12]

Swallowing

Swallowing involves the coordinated relaxation and contraction of muscles surrounding the tongue, mouth, pharynx, larynx, and upper esophagus. These actions constitute a complex sensorimotor behavior. The suprahyoid and infrahyoid muscles are among the most well-documented muscles involved in swallowing.[13][14] The omohyoid, sternothyroid, sternohyoid, and portions of the infrahyoid muscles help depress the hyolaryngeal complex, while the suprahyoid muscles influence the anterosuperior movements of the hyoid bone. During swallowing, the thyrohyoid muscle moves the larynx anterosuperiorly. Additionally, the hyoid bone is moved anteriorly by the infrahyoid and suprahyoid muscles, supporting the opening of the upper esophageal sphincter.[15][16][17]

The Hyoid and Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome

Obstructive sleep apnea is a chronic sleep-related breathing disorder characterized by repeated narrowing and obstruction of the pharyngeal airway during sleep.[18] Pharyngeal collapsibility, caused by the loss of wakefulness stimulus and changes in neuromuscular control, contributes to this condition. Several factors influence pharyngeal collapsibility, with hyoid position being one such factor. An imbalance between the suprahyoid and infrahyoid muscles may alter the position of the hyoid, affecting airway patency and increasing pharyngeal collapsibility.[19]

Clinical manifestations include nonrefreshing sleep, daytime sleepiness, fatigue, nocturia, irritability, and morning headaches. If unmanaged, the condition may lead to complications such as cardiovascular diseases, cognitive impairment, and reduced productivity, increasing the risk of road traffic accidents. Nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is the treatment of choice. If unsuccessful, alternatives include oral devices, positional therapy, and upper airway surgery, such as genioglossus advancement, hyoidothyroidopexy (hyoid suspension), hyoid myotomy, and sliding genioplasty.[20][21][22]

Clinical Significance

Hyoid Bone Insertion Tendinitis

Hyoid bone insertion tendinitis, also known as hyoid bone syndrome, is characterized by neck pain that worsens with swallowing and neck movement. The pain is typically described as either dull or sharp, radiating to the temporal area, posterior pharyngeal wall, sternocleidomastoid muscle, ear, and supraclavicular region. Examination reveals tenderness over the greater horn of the hyoid upon palpation. Diagnosis is primarily based on patient history and physical examination, with imaging used to rule out other potential causes. Initial treatment involves medical therapy, including topical and systemic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, local anesthetics, and steroid injections. Surgical intervention may be considered if medical therapy is ineffective.[23]

Infrahyoid Muscle Paralysis

Infrahyoid muscle paralysis typically manifests as difficulty swallowing, throat tightness, and a hoarse voice. This condition often results from cervical spine trauma that damages the ansa cervicalis. Most infrahyoid muscles receive innervation from the ansa cervicalis in their lower half. Consequently, damage to these nerves can occur during surgical procedures, such as neck dissection for malignant tumor excision, leading to muscle paralysis.

Calcified Stylohyoid Ligament and Eagle Syndrome

Calcification of the stylohyoid ligament, which connects the lesser horn of the hyoid to the tip of the styloid process, can lead to symptoms similar to those of Eagle syndrome. The condition may involve unilateral or bilateral calcification, which may be partial or complete. In some cases, affected individuals may have incidental calcification without symptoms.[24] Eagle syndrome occurs in about 4% of the population and typically causes unilateral, sharp, shooting pain in the jaw that radiates to the throat, tongue, or ear. This pain often worsens with neck movement and is accompanied by difficulty swallowing, a sore throat, and tinnitus. Another potential cause of the syndrome is an elongated styloid process (≥ 3 cm).[25]

Eagle syndrome can be classified into 2 types. The 1st, classic Eagle syndrome, often follows tonsillectomy and presents with pharyngodynia in the tonsillar fossa. Symptoms include odynophagia, dysphagia, foreign body sensation, hypersalivation, and, rarely, voice changes. These symptoms occur as the tonsillectomy scar tissue moves along the tip of an elongated styloid process during functional movements.

The 2nd type, stylocarotid syndrome, results from compression of the internal or external carotid arteries and their perivascular sympathetic fibers. This compression leads to constant pain radiating to the carotid region, including chronic neck pain, headache, pain with head movement, and eye pain. Other symptoms may include vertigo and ear pain. Patients with these symptoms may seek care from otolaryngology, dental, neurosurgical, or ophthalmology specialists. Calcification of the stylohyoid ligament can also contribute to this syndrome, although it often remains asymptomatic.[26]

Differential diagnoses for Eagle syndrome include temporomandibular joint disorders, temporal arteritis, glossopharyngeal, sphenopalatine, or trigeminal neuralgias, mastoiditis, dental pain, hyoid bursitis, cluster headaches, and migraines. Imaging is crucial for diagnosis, as an elongated styloid process, typically greater than 2 inches, is the most common sign. Treatment options include both medical and surgical. Medical therapies include antihistamines, neuroleptics, vasodilators, tranquilizers, antidepressants, steroid injections, and local anesthetics. Surgery is considered when medical management fails, but recurrences have been reported after surgical intervention.[27]

Other Issues

Forensic Anatomy of the Hyoid

The forensic profile of the hyoid in anthropology centers on age estimation and sex determination. Fusion of the greater horns with the hyoid body provides insight into adult age prediction, while bone density serves as a reliable indicator for both age and sex. However, studies have reported considerable variation in the degree and timing of fusion. Discriminant function analysis of hyoid measurements supports their usefulness in estimating sex.[28]

Forensic Significance of Hyoid Fractures

Trauma to the hyoid and the laryngeal cartilages, including the thyroid and cricoid, is a key forensic indicator of manual strangulation. Fractures of the hyoid-laryngeal complex occur in deaths involving constrictive forces around the neck and have been extensively documented in cases of manual and ligature strangulation, as well as hanging. Blunt neck trauma may also produce hyoid fractures.

Injuries typically involve the greater horns or the junction between the body and horns of the hyoid, often presenting as vertical or oblique fractures, with segment displacement. Bilateral fractures and double fractures of a single greater horn are not uncommon.[29] Although hyoid fractures are more frequent in strangulation than in hanging, they appear in only about 1/3 of strangulation-related homicides. An intact hyoid, therefore, does not exclude strangulation as the cause of death.

Fractures are more common in older individuals due to progressive ankylosis at the junction between the greater horns and the body. In contrast, younger adults between 20 and 40 years of age are less likely to exhibit such injuries.[30] Natural mobility at this junction must not be misinterpreted as a fracture, eg, during postmortem examination.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Auvenshine RC DDS, PhD, Pettit NJ DMD, MSD. The hyoid bone: an overview. Cranio : the journal of craniomandibular practice. 2020 Jan:38(1):6-14. doi: 10.1080/08869634.2018.1487501. Epub 2018 Oct 5 [PubMed PMID: 30286692]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencede Bakker BS, de Bakker HM, Soerdjbalie-Maikoe V, Dikkers FG. The development of the human hyoid-larynx complex revisited. The Laryngoscope. 2018 Aug:128(8):1829-1834. doi: 10.1002/lary.26987. Epub 2017 Dec 8 [PubMed PMID: 29219191]

Fisher E, Austin D, Werner HM, Chuang YJ, Bersu E, Vorperian HK. Hyoid bone fusion and bone density across the lifespan: prediction of age and sex. Forensic science, medicine, and pathology. 2016 Jun:12(2):146-57. doi: 10.1007/s12024-016-9769-x. Epub 2016 Apr 25 [PubMed PMID: 27114259]

Khan YS, Fakoya AO, Bordoni B. Anatomy, Head and Neck: Suprahyoid Muscle. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31536316]

Lettau J, Bordoni B. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Lingual Artery. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32119400]

Toth J, Lappin SL. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Mylohyoid Muscle. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31424877]

Kulzer MH, Branstetter BF 4th. Chapter 1 Neck Anatomy, Imaging-Based Level Nodal Classification and Impact of Primary Tumor Site on Patterns of Nodal Metastasis. Seminars in ultrasound, CT, and MR. 2017 Oct:38(5):454-465. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2017.05.002. Epub 2017 May 20 [PubMed PMID: 29031363]

Bajaj AK, Dave N, Garasia MB. A rare case of oral fetus in fetu with mandibular cleft and absent hyoid. Paediatric anaesthesia. 2011 Jun:21(6):706-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2011.03577.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21518110]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMORI M. STATISTICS ON THE MUSCULATURE OF THE JAPANESE. Okajimas folia anatomica Japonica. 1964 Oct:40():195-300 [PubMed PMID: 14213705]

Chaudhary P, Singh Z, Khullar M, Arora K. Levator glandulae thyroideae, a fibromusculoglandular band with absence of pyramidal lobe and its innervation: a case report. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR. 2013 Jul:7(7):1421-4. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/6144.3186. Epub 2013 Jul 1 [PubMed PMID: 23998080]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBersu ET. Anatomical analysis of the developmental effects of aneuploidy in man: the Down syndrome. American journal of medical genetics. 1980:5(4):399-420 [PubMed PMID: 6446859]

Lemaire V, Jacquemin G, Nelissen X, Heymans O. Tip of the greater horn of the hyoid bone: a landmark for cervical surgery. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2005 Mar:27(1):33-6 [PubMed PMID: 15592932]

Chang MC, Park S, Cho JY, Lee BJ, Hwang JM, Kim K, Park D. Comparison of three different types of exercises for selective contractions of supra- and infrahyoid muscles. Scientific reports. 2021 Mar 30:11(1):7131. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-86502-w. Epub 2021 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 33785793]

Park D, Lee HH, Lee ST, Oh Y, Lee JC, Nam KW, Ryu JS. Normal contractile algorithm of swallowing related muscles revealed by needle EMG and its comparison to videofluoroscopic swallowing study and high resolution manometry studies: A preliminary study. Journal of electromyography and kinesiology : official journal of the International Society of Electrophysiological Kinesiology. 2017 Oct:36():81-89. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2017.07.007. Epub 2017 Jul 25 [PubMed PMID: 28763682]

Hara K, Tohara H, Minakuchi S. Treatment and evaluation of dysphagia rehabilitation especially on suprahyoid muscles as jaw-opening muscles. The Japanese dental science review. 2018 Nov:54(4):151-159. doi: 10.1016/j.jdsr.2018.06.003. Epub 2018 Sep 8 [PubMed PMID: 30302133]

Nguyen JD, Duong H. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Cheeks. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31536265]

Park D, Suh JH, Kim H, Ryu JS. The Effect of Four-Channel Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation on Swallowing Kinematics and Pressures: A Pilot Study. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation. 2019 Dec:98(12):1051-1059. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001241. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31180928]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOsman AM, Carter SG, Carberry JC, Eckert DJ. Obstructive sleep apnea: current perspectives. Nature and science of sleep. 2018:10():21-34. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S124657. Epub 2018 Jan 23 [PubMed PMID: 29416383]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSforza E, Bacon W, Weiss T, Thibault A, Petiau C, Krieger J. Upper airway collapsibility and cephalometric variables in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2000 Feb:161(2 Pt 1):347-52 [PubMed PMID: 10673170]

Jordan AS, McSharry DG, Malhotra A. Adult obstructive sleep apnoea. Lancet (London, England). 2014 Feb 22:383(9918):736-47. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60734-5. Epub 2013 Aug 2 [PubMed PMID: 23910433]

Barrera JE. Virtual surgical planning improves surgical outcome measures in obstructive sleep apnea surgery. The Laryngoscope. 2014 May:124(5):1259-66. doi: 10.1002/lary.24501. Epub 2013 Dec 6 [PubMed PMID: 24357526]

Tantawy AA, Askar SM, Amer HS, Awad A, El-Anwar MW. Hyoid Bone Suspension as a Part of Multilevel Surgery for Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome. International archives of otorhinolaryngology. 2018 Jul:22(3):266-270. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1607227. Epub 2017 Oct 25 [PubMed PMID: 29983767]

Aydil U, Ekinci O, Köybaşioğlu A, Kizil Y. Hyoid bone insertion tendinitis: clinicopathologic correlation. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2007 May:264(5):557-60 [PubMed PMID: 17203309]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceÖztaş B, Orhan K. Investigation of the incidence of stylohyoid ligament calcifications with panoramic radiographs. Journal of investigative and clinical dentistry. 2012 Feb:3(1):30-5. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1626.2011.00081.x. Epub 2011 Aug 5 [PubMed PMID: 22298518]

Warrier S A, Kc N, K S, Harini DM. Eagle's Syndrome: A Case Report of a Unilateral Elongated Styloid Process. Cureus. 2019 Apr 10:11(4):e4430. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4430. Epub 2019 Apr 10 [PubMed PMID: 31245217]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRao PP, Menezes RG, Naik R, Venugopal A, Nagesh KR, Madhyastha S, Kanchan T, Gupta A, Lasrado S. Bilateral calcified stylohyoid ligament: an incidental autopsy finding with medicolegal significance. Legal medicine (Tokyo, Japan). 2010 Jul:12(4):184-7. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2010.03.002. Epub 2010 Apr 7 [PubMed PMID: 20378390]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJain S, Bansal A, Paul S, Prashar DV. Styloid-stylohyoid syndrome. Annals of maxillofacial surgery. 2012 Jan:2(1):66-9. doi: 10.4103/2231-0746.95326. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23483633]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBalseven-Odabasi A, Yalcinozan E, Keten A, Akçan R, Tumer AR, Onan A, Canturk N, Odabasi O, Hakan Dinc A. Age and sex estimation by metric measurements and fusion of hyoid bone in a Turkish population. Journal of forensic and legal medicine. 2013 Jul:20(5):496-501. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2013.03.022. Epub 2013 May 10 [PubMed PMID: 23756521]

Khokhlov VD. Trauma to the hyoid bone and laryngeal cartilages in hanging: review of forensic research series since 1856. Legal medicine (Tokyo, Japan). 2015 Jan:17(1):17-23. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2014.09.005. Epub 2014 Oct 5 [PubMed PMID: 25456050]

Pollanen MS, Chiasson DA. Fracture of the hyoid bone in strangulation: comparison of fractured and unfractured hyoids from victims of strangulation. Journal of forensic sciences. 1996 Jan:41(1):110-3 [PubMed PMID: 8934706]