Introduction

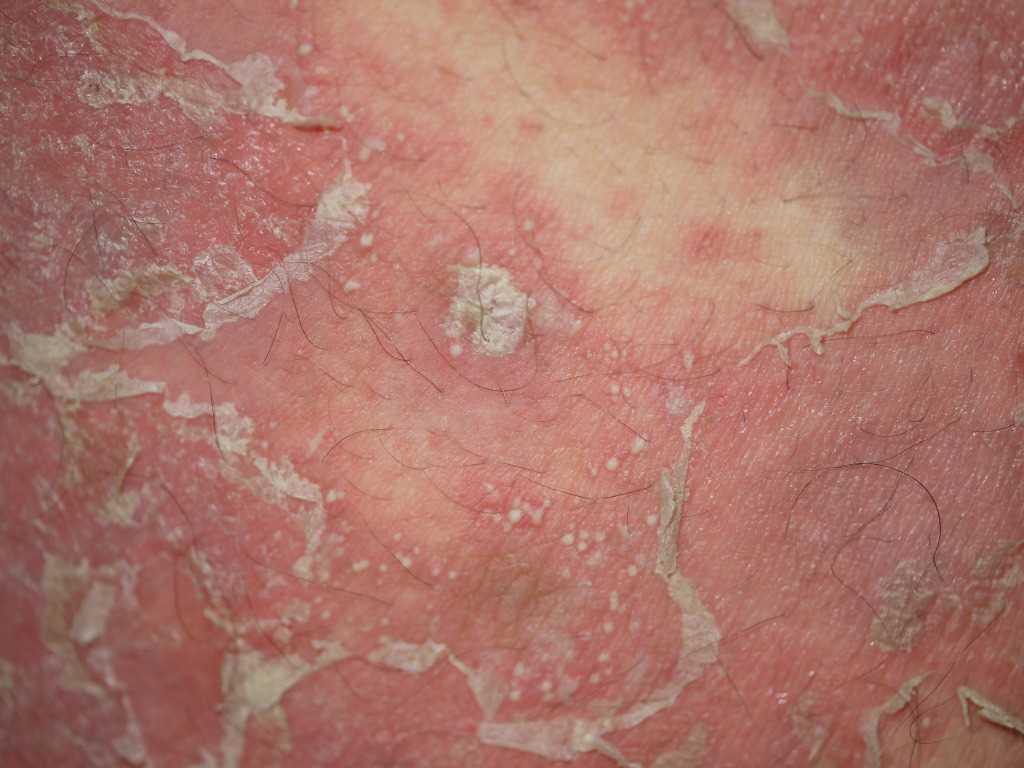

Pustular psoriasis is a rare and severe variant of psoriasis characterized by the eruption of sterile pustules, which may present in distinct clinical patterns. The pathologic features of psoriasis, including keratinocyte hyperproliferation, neutrophilic infiltration, and immune dysregulation, are markedly accentuated. Generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) displays clinical heterogeneity in age of onset, severity, and disease course. Several overlapping phenotypes are recognized. A variable relationship exists between GPP and plaque psoriasis. Some individuals experience plaque psoriasis before or after GPP episodes, while others exhibit GPP as the sole phenotype without any history of plaque involvement (see Image. Pustular Psoriasis).[1][2][3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

GPP may be triggered or exacerbated by a variety of factors. Some patients with a pustular psoriasis phenotype exhibit features of an autoinflammatory disorder linked to specific genetic mutations. This category includes deficiency of the interleukin-36 (IL-36) receptor antagonist (DITRA) and deficiency of the interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor antagonist (DIRA).

Infectious triggers, particularly bacterial and viral pathogens, are commonly reported. Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus epidermidis have been implicated in disease exacerbation.[4] Drug-induced flares are also well documented. Among pharmacologic agents, corticosteroids are most strongly associated with disease provocation. Both the abrupt withdrawal of systemic corticosteroids and the use of potent topical corticosteroids under occlusion have been linked to disease onset.[5][6] Flare induction following withdrawal of cyclosporin has also been reported.[7] Other agents occasionally associated with GPP include terbinafine, propranolol, bupropion, lithium, phenylbutazone, salicylates, and potassium iodide. Topical therapies such as coal tar and dithranol may precipitate pustulation if applied inappropriately during unstable disease.[8]

Psychological stress is frequently cited as a worsening factor. Hypocalcemia may either result from GPP or serve as a trigger, particularly when caused by hypoparathyroidism.[9] Pregnancy-associated pustular psoriasis, historically referred to as "impetigo herpetiformis," is a specific variant associated with increased risk of stillbirth and fetal anomalies.[10]

Epidemiology

GPP is a rare condition with variable epidemiologic characteristics. In France, the age- and sex-standardized cumulative prevalence and incidence rates have been reported as 45.2 and 7.1 per million, respectively.[11] In Japan, the estimated prevalence is 7.46 per million.[12]

The mean age at diagnosis for adult patients with pustular psoriasis ranges from 48 to 50 years, although the average age of onset for acute GPP is younger, around 31 years.[13] Palmoplantar pustulosis and acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau have reported mean onset ages of 43.7 and 51.8 years, respectively.[14] Pediatric GPP is uncommon but well-documented. Affected children typically present between 6 weeks and 10 years of age, with 1 reported case involving a 6-week-old infant.[15] Annular pustular psoriasis in children has a mean age of onset of approximately 6 years.[16]

The sex distribution of GPP varies by geography. The male-to-female ratio in the U.S. is approximately 1:1. Globally, a female predominance has been observed, with reported female-to-male ratios of 1.5 for acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau, 1.7 for GPP, and 3.5 for palmoplantar pustulosis.[17][18] Common comorbid conditions include hypertension, ischemic heart disease, and hyperlipidemia.

Pathophysiology

Deleterious germline mutations in IL36RN have been identified in both familial and sporadic cases of GPP across diverse populations, including those from the U.K., Germany, Tunisia, Malaysia, China, and Japan. These mutations vary among populations, with evidence supporting a founder effect. In Europeans, the most common mutation, IL36RN p.Ser113Leu, occurs in approximately 0.03% of the healthy population. Patients with GPP harboring IL36RN mutations are more likely to experience early-onset disease and exhibit a pronounced systemic inflammatory response.[19][20]

IL36RN encodes the IL-36 receptor antagonist (IL-36Ra), which is primarily expressed in the skin and functions as an antagonist to 3 proinflammatory IL-1 family cytokines: IL-36α, IL-36β, and IL-36γ. These cytokines activate intracellular signaling cascades, including the NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways, and are modulated by cytokines released by T helper 17 (Th17) cells and tumor necrosis factor α. While IL-36 cytokines are also overexpressed in plaque psoriasis, the mechanisms of IL-36 dysregulation in GPP appear to differ.

IL-36 receptors are constitutively expressed on dermal dendrocytes, CD4+ T cells, and macrophages. Receptor activation promotes the maturation of monocyte-derived dendritic cells and the release of cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-23, tumor necrosis factor α, and interferon γ, all of which contribute to neutrophil recruitment and cutaneous inflammation.

Mutations in CARD14 have been occasionally reported, particularly among individuals with coexistent plaque psoriasis. These mutations lead to increased activation of NF-κB signaling and elevated expression of IL-8 and IL-36γ. Mutations in AP1S3, more commonly observed in patients with GPP and acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau, result in increased IL-36α expression and impair innate immune responses by disrupting Toll-like receptor 3 signaling.

IL-6 signaling has gained attention for its role in the pathogenesis of pustular psoriasis. The IL-6 receptor exists in both membrane-bound and soluble forms, a feature that distinguishes it from other cytokine receptors, which are exclusively membrane-bound. The IL-6/IL-6 receptor complex, together with the ubiquitously expressed gp130 subunit, activates the JAK/STAT and RAS/MEK/ERK/MAPK signaling pathways, promoting downstream gene transcription.

IL-6 exerts broad immunologic effects, including the induction of acute-phase protein synthesis, maturation of B cells, differentiation of T cells, and promotion of Th17 cell development. IL-6 also stimulates neutrophil maturation from myeloid precursors, upregulates ICAM-1 and other endothelial adhesion molecules to facilitate neutrophil migration, and enhances the production of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-23 and IL-17, reinforcing the Th17-driven inflammatory loop.[21]

Histopathology

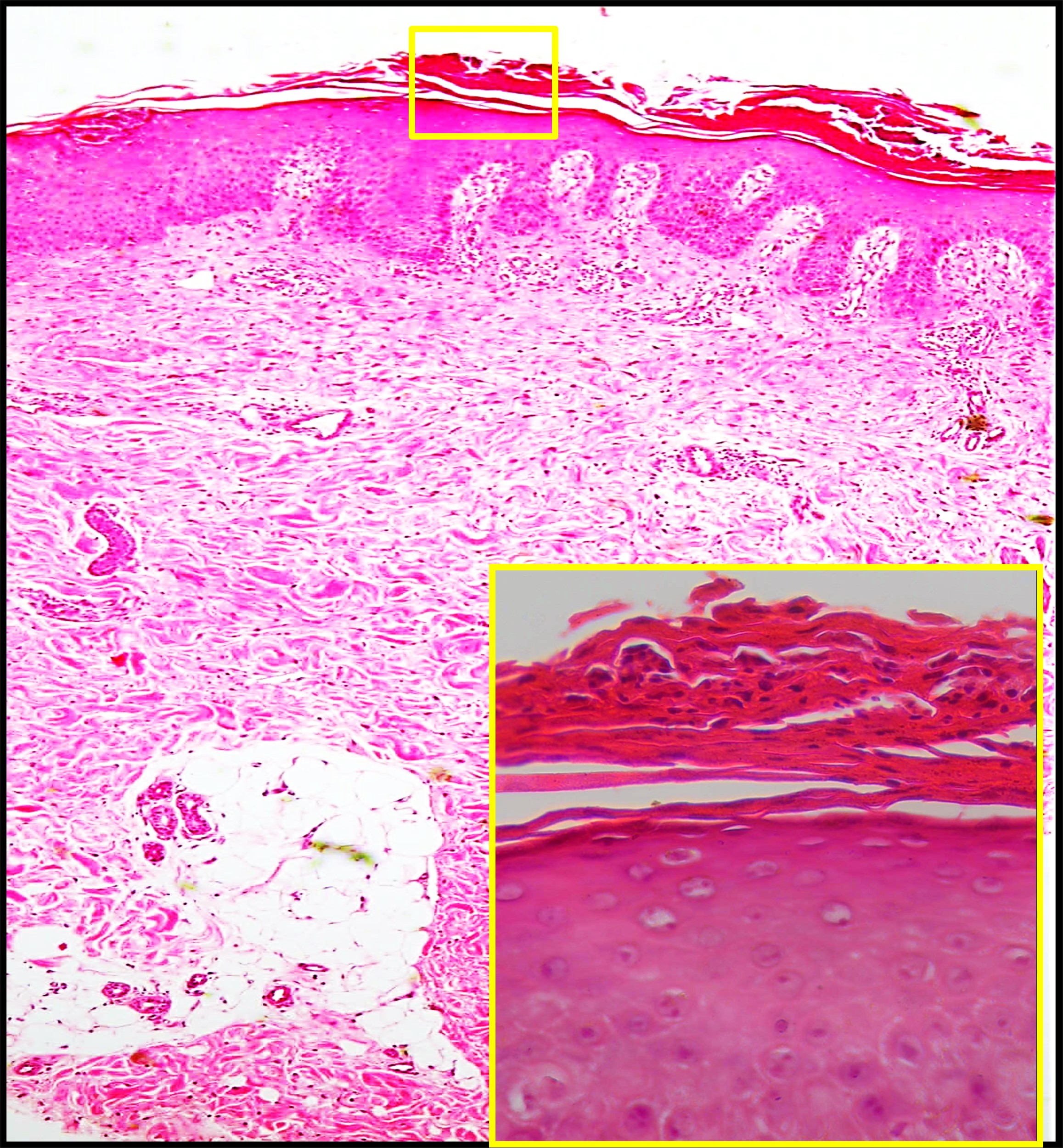

The histologic findings in GPP are dominated by dense neutrophilic infiltration, which underlies the bright erythema and formation of sterile pustules. The defining feature is the accumulation of neutrophils within the epidermis. The epidermis is typically acanthotic, and numerous neutrophils are found between eosinophilic strands of keratinocytes. Large neutrophilic aggregates often localize in the stratum corneum, typically surrounded by parakeratosis. Hallmark features of active pustular psoriasis include exaggerated spongiform pustules of Kogoj and microabscesses of Munro, which represent characteristic histologic patterns also seen in plaque psoriasis (see Image. Histopathology of Pustular Psoriasis).

Despite these features, the National Psoriasis Foundation's consensus statement advises that a skin biopsy is not essential for diagnosing GPP, as histologic findings may be nonspecific. Notably, the histopathologic features of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) may closely resemble those of GPP. Consequently, clinical history and presentation are generally more reliable than histologic examination for distinguishing between these entities.[22]

History and Physical

Pustular psoriasis may develop in individuals with longstanding plaque psoriasis, often following exposure to corticosteroids or other environmental triggers. Alternatively, onset may be de novo, frequently after an infection. In either scenario, the earliest symptom is often a burning sensation in the skin, which subsequently becomes dry and tender. Although not universally present, these prodromal signs are typically followed by the abrupt onset of high fever and severe malaise. Preexisting psoriatic plaques may evolve into numerous small pustules. Erythema intensifies, and pustules spread to previously unaffected areas, particularly the flexural and genital regions.

The cutaneous findings vary and may include discrete pustules, lakes of pus, circinate lesions, erythematous plaques covered with pustules, or generalized erythroderma. Pustules often emerge in crops, with subsequent desiccation and exfoliation. Nail involvement may include thickening and the formation of subungual collections of pus. Oral and oropharyngeal mucosa may be affected, with findings such as hyperemia, geographic tongue, or fissured tongue. Some individuals report associated arthralgia. The disease may resolve spontaneously within days to weeks, reverting to baseline psoriasis in some cases or progressing to erythroderma in others.[23][24]

Clinical subtypes of GPP are defined by distinct morphological patterns and differences in natural history. Recognition of these subtypes is essential for accurate diagnosis and appropriate management.

The von Zumbusch pattern represents the most acute and fulminant form of GPP. Named after Leo von Zumbusch, who first described the condition in 1910 in 2 siblings following topical treatment, this variant presents with widespread erythema, sterile pustulation, fever, systemic malaise, and skin tenderness. Diagnosis is based on clinical findings, laboratory abnormalities such as leukocytosis and elevated inflammatory markers (erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein), and histopathologic evidence of spongiform pustules. Pustules typically resolve within days, followed by prominent scaling. Chronic plaques of psoriasis may clear after the acute episode. In the original case, 9 recurrences were documented over a 10-year period.

The annular pattern is characterized by erythematous, scaly lesions with pustulation along the advancing margin. These lesions expand centrifugally over hours to days while simultaneously undergoing central clearing. Sometimes referred to as "subacute GPP" or the "circinate variant," this form generally follows a subacute or chronic course and produces fewer systemic symptoms. The condition appears with higher frequency in the pediatric population.

The exanthematic type manifests as a sudden eruption of small pustules that resolve spontaneously within a few days. This form typically follows an infection or may be drug-induced, with lithium being a common trigger. Systemic symptoms are usually absent. Clinical and histologic overlap with pustular drug eruptions, particularly AGEP, complicates differentiation.

The localized pattern involves the appearance of pustules within or at the periphery of existing psoriatic plaques. This variant is often observed during unstable phases of chronic plaque psoriasis or after the application of irritants such as coal tar or anthralin.

"Impetigo herpetiformis" refers to GPP occurring during pregnancy. Although onset most often occurs in the 3rd trimester, cases have been reported as early as the 1st month of gestation or during the immediate postpartum period. The eruption typically begins on flexural surfaces as symmetrical, confluent pustules on inflamed skin, often starting in the groin. Lesions spread centrifugally, coalesce into plaques, and may leave reddish-brown pigmentation during healing. Mucosal involvement, including the tongue, oral cavity, and esophagus, may occur and can be erosive. The disease frequently persists until delivery and may continue into the postpartum period.[25]

GPP begins within the 1st year of life in approximately 30% of cases. Onset may occur during the first few weeks, and, in some instances, the disease may be present at birth. Systemic symptoms are frequently absent in infancy, and mild cases may not require treatment. Lesions are often localized to flexural areas, such as the neck, and may persist in that distribution for extended periods. However, more severe presentations with systemic involvement necessitate active intervention.

Disease onset in children most commonly occurs between 2 and 10 years of age. While the von Zumbusch pattern may be observed, annular and circinate variants are more frequently encountered. Episodes may resolve within days, but recurrent inflammatory relapses are not uncommon. In older children, clinical features resemble the adult form, and any of the established morphological patterns may be present.

Evaluation

Laboratory evaluation of GPP often reveals erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein levels, reflecting systemic inflammation. An initial absolute lymphopenia is commonly followed by marked polymorphonuclear leukocytosis, which may reach 40,000/µL. Hypoalbuminemia, hypocalcemia, and reduced plasma zinc levels are frequently observed, along with lipid profile abnormalities. Bacterial cultures of pustular fluid are typically negative unless secondary infection is present. Viral cultures and Tzanck smears are also negative. However, disruption of the epidermal barrier may predispose to bacteremia. Urinalysis may demonstrate albuminuria and urinary casts.

Treatment / Management

Patients with GPP flares may require hospitalization to ensure adequate hydration, bed rest, and prevention of excessive heat loss. Supportive care includes bland topical compresses and saline or oatmeal baths, which help relieve discomfort and promote debridement of affected skin.

Initiation of systemic therapy is recommended alongside supportive interventions. According to the National Psoriasis Foundation Medical Board, 1st-line systemic agents for GPP in adults include oral retinoids (acitretin, isotretinoin), methotrexate, cyclosporine, infliximab, and spesolimab. In pediatric populations, effective 1st-line therapies include acitretin, cyclosporine, methotrexate, and etanercept.

Spesolimab is a selective, humanized monoclonal antibody targeting the IL-36 receptor. This agent was recently approved in both Europe and the U.S. for the treatment of GPP flares in adults. In phase II randomized controlled trials, spesolimab produced rapid and effective cutaneous clearance during acute flares and demonstrated superiority to placebo in reducing flare frequency over 48 weeks of maintenance treatment. The safety and tolerability profiles were favorable.[26](A1)

In March 2024, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted an expanded indication for spesolimab to include adults and pediatric patients aged 12 years or older weighing at least 40 kg. (Source: U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2024) This decision was based on results from the 48-week Effisayil 2 clinical trial, which enrolled 123 participants. Individuals treated with spesolimab experienced an 84% reduction in GPP flares compared to those receiving a placebo.[27](A1)

Second-line therapies for GPP include biologic agents such as etanercept, adalimumab, ustekinumab, and secukinumab, as well as topical treatments, particularly corticosteroids, calcipotriene, and tacrolimus, for localized involvement of the palms and soles.[28] A small case series reported clinical improvement with bimekizumab in patients with palmoplantar pustulosis and palmoplantar plaque psoriasis presenting with pustules.[29] Formal treatment guidelines for 2nd-line therapies are lacking. Anecdotal evidence has described paradoxical induction of pustular psoriasis with certain biologics, highlighting the need for further evaluation and consensus.[30](B3)

Tocilizumab, an IL-6 receptor inhibitor, has demonstrated efficacy in select cases of biologic-induced plantar pustular psoriasis.[31] This monoclonal antibody targets both membrane-bound and soluble IL-6 receptor complexes, thereby blocking IL-6-dependent STAT1/STAT3 signaling. Notably, tocilizumab has also been associated with the paradoxical development of psoriasiform dermatitis in patients treated for rheumatoid arthritis.[32](B2)

Tofacitinib, a JAK inhibitor, has been investigated for the treatment of psoriasis, although its effectiveness in GPP remains uncertain.[33] While literature on phototherapy for GPP is limited, narrow-band UV-B has shown promise and may offer clinical benefits comparable to PUVA in other psoriasis subtypes.[34]

Differential Diagnosis

GPP is a clinically heterogeneous condition with variable manifestations, making accurate diagnosis and differentiation from other pustular dermatoses challenging. The differential diagnosis includes disorders characterized by widespread nonfollicular pustules. During the acute phase, the presence of fever, leukocytosis, and elevated inflammatory markers may mimic systemic infection. This resemblance can result in the inappropriate discontinuation of immunosuppressive therapy, potentially worsening the underlying disease.

Several other conditions may mimic the presentation of GPP and should be considered in the differential diagnosis. AGEP presents as a febrile eruption with erythema and widespread pustules. Histopathologic features include neutrophilic exocytosis, intraepidermal or subcorneal pustules, papillary dermal edema, and a dermal infiltrate composed of neutrophils and eosinophils. AGEP is most often triggered by medications or infections and typically resolves within 2 weeks following removal of the inciting factor.

Although AGEP shares clinical features with GPP, such as sudden onset of pustules, fever, and leukocytosis, it may be distinguished by the presence of numerous discrete, short-lived pustules, a recent history of drug exposure, and rapid resolution after drug cessation. Consensus among experts (90%) supports that the presence of eosinophils, particularly within microabscesses, supports a diagnosis of drug-induced pustulosis.[35] AGEP has been associated with IL36RN mutations, similar to those identified in GPP, palmoplantar pustulosis, and acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. These genetic and clinical overlaps have led some to consider AGEP a drug-induced variant of pustular psoriasis.[36]

Subcorneal pustular dermatosis, or Sneddon–Wilkinson disease, is another condition characterized by erythematous pustules, often affecting the trunk and intertriginous areas. The association of this disease with pustular psoriasis remains controversial. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis is typically benign, relapsing, and unaccompanied by systemic symptoms. A diagnostic clue is the presence of hypopyon pustules, which contain clear fluid in the upper portion and purulent yellow material in the lower half.[37] Immunoglobulin A pemphigus may also mimic GPP, but histopathological findings and characteristic immunofluorescence patterns help distinguish this condition. The necrolytic migratory erythema of glucagonoma can resemble pustular psoriasis but is typically accompanied by wasting, glossitis, and anemia, which aid in differentiation.

Prognosis

The prognosis of GPP varies by subtype, age group, and underlying triggers. Subacute annular and circinate forms are generally associated with a favorable outcome, particularly in pediatric patients. Prognosis is also more favorable when a clear precipitating factor is identified, as seen in GPP of pregnancy. In contrast, GPP evolving from acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau appears to carry the poorest prognosis.[38][39]

Outcomes are less favorable in older adults, who face a higher risk of complications. Mortality in this group may result from sepsis or multi-organ failure—renal, hepatic, or cardiorespiratory—during the acute erythrodermic phase. The overall prognosis in children is good, especially when severe secondary infections are effectively prevented.

Complications

Reported mortality rates for GPP range from 4% to 24%, underscoring the potential severity of the condition.[40] Patients are often systemically unwell and may experience life-threatening complications during the acute phase.

Renal compromise may arise due to hypovolemia and oligemia, potentially resulting in acute kidney injury. Profound hypoalbuminemia is common and results from both the rapid loss of plasma proteins into tissues and impaired intestinal absorption. Secondary hypocalcemia may develop as a consequence of low albumin levels. Abnormalities in liver function tests are frequently observed, and in some cases, cholestatic jaundice may occur due to neutrophilic cholangitis.[41] Though rare, acute respiratory distress syndrome has been reported.

Superimposed Staphylococcus aureus infection may complicate the disease course. Telogen effluvium, a form of diffuse hair shedding, can occur 2 to 3 months after the acute illness. Amyloidosis is a rare late complication associated with chronic inflammation.

In the setting of impetigo herpetiformis, additional complications may include delirium, gastrointestinal disturbances, tetany, cardiac or renal failure, and in severe cases, death. The risk of placental insufficiency is elevated, increasing the likelihood of stillbirth, neonatal death, or congenital anomalies. These obstetric complications are directly related to the severity and chronicity of the disease. Recurrence is common in subsequent pregnancies and may also occur with the use of oral contraceptives.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with psoriasis vulgaris should be educated about warning signs suggestive of GPP, particularly when predisposing factors such as infections, medications, or psychological stress are present. Concerning indicators include the sudden appearance of a rash over existing plaques, fever, and myalgia. Pregnant individuals with rapidly worsening psoriasis should be closely monitored by a dermatologist throughout the course of pregnancy. Genetic testing is recommended in infants presenting with early-onset psoriasis to assess for underlying mutations associated with pustular phenotypes.

Pearls and Other Issues

GPP is a complex, systemic inflammatory disorder that requires careful clinical judgment for diagnosis and ongoing management. Recognition of the varied presentations of this disease is essential for prompt and appropriate care.

GPP is characterized by diffuse erythema and sterile pustules, which may occur with or without systemic symptoms, laboratory abnormalities, or concomitant psoriasis subtypes. The condition may present acutely with widespread pustules or subacutely with an annular pattern. In some cases, the disease begins as isolated pustules that may progress into larger collections or “lakes of pus.”

The presence of several persistent, discrete pustules without coalescence, or the identification of hypopyon pustules, may prompt clinicians to perform a skin biopsy to confirm the diagnosis and exclude other mimickers. However, features such as desquamation, scaling, and crusting, which reflect pustule evolution, are not required for diagnosis.

Systemic findings such as fever, fatigue, leukocytosis with neutrophilia, and elevated CRP, while not essential, can support the clinical suspicion of GPP. A skin biopsy is not mandatory for diagnosis but is strongly recommended to rule out alternative conditions.

Laboratory abnormalities, including hypocalcemia, hypoproteinemia, hypoalbuminemia, and abnormal liver or kidney function, are not diagnostic criteria but should be regularly monitored to detect complications. Genetic testing is not required for diagnosis. However, IL36RN mutation screening is advised if accessible. Mutations in IL36RN have been associated with a more severe disease phenotype, marked by earlier onset, heightened systemic inflammation, and increased frequency of disease flares.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Psoriasis is typically managed by dermatologists, though primary care clinicians often provide long-term follow-up for most patients. One rare form of the disease is pustular psoriasis, which is defined by the presence of sterile pustules that may follow various clinical patterns. All of the pathological features of psoriasis are heightened in this form.

GPP is clinically heterogeneous, varying in age of onset, severity, and natural course. While its treatment aligns with general psoriasis management, the acute stage of GPP can be life-threatening without prompt and appropriate intervention. Prognosis is typically favorable in subacute annular and circinate variants, and thus more optimistic in children. Among GPP cases, outcomes are better when a clear precipitating factor can be identified.

Timely recognition and management of GPP are critical to reducing morbidity and mortality. Optimal care requires a coordinated, interprofessional approach to ensure patient-centered treatment and improve outcomes. Healthcare professionals, including dermatologists, emergency physicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, and pharmacists, must be equipped with the clinical expertise to recognize GPP’s varied presentations and underlying triggers, distinguish it from other conditions, initiate appropriate therapy, and monitor for complications.

Patient and caregiver education is also vital. Counseling should address potential triggers, the importance of medication adherence, and early warning signs of disease progression, all of which are key to minimizing morbidity and preventing disease exacerbations.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Histopathology of Pustular Psoriasis. Low-power view (H&E, ×100) shows regular psoriasiform acanthosis with overlying subcorneal neutrophilic collections. High-power inset (H&E, ×400) highlights neutrophilic microabscesses in the stratum corneum consistent with pustule formation.

Contributed by Mona Abdel-Halim Ibrahim, MD

References

Nagai M, Imai Y, Wada Y, Kusakabe M, Yamanishi K. Serum Procalcitonin and Presepsin Levels in Patients with Generalized Pustular Psoriasis. Disease markers. 2018:2018():9758473. doi: 10.1155/2018/9758473. Epub 2018 Dec 16 [PubMed PMID: 30647802]

Peccerillo F, Odorici G, Ciardo S, Conti A, Pellacani G. Evaluation of generalized pustular psoriasis by reflectance confocal microscopy. Skin research and technology : official journal of International Society for Bioengineering and the Skin (ISBS) [and] International Society for Digital Imaging of Skin (ISDIS) [and] International Society for Skin Imaging (ISSI). 2019 May:25(3):402-403. doi: 10.1111/srt.12655. Epub 2019 Jan 5 [PubMed PMID: 30614082]

Akiyama M. Early-onset generalized pustular psoriasis is representative of autoinflammatory keratinization diseases. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2019 Feb:143(2):809-810. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.11.009. Epub 2019 Jan 1 [PubMed PMID: 30606494]

Cassandra M, Conte E, Cortez B. Childhood pustular psoriasis elicited by the streptococcal antigen: a case report and review of the literature. Pediatric dermatology. 2003 Nov-Dec:20(6):506-10 [PubMed PMID: 14651571]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBrenner M, Molin S, Ruebsam K, Weisenseel P, Ruzicka T, Prinz JC. Generalized pustular psoriasis induced by systemic glucocorticosteroids: four cases and recommendations for treatment. The British journal of dermatology. 2009 Oct:161(4):964-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09348.x. Epub 2009 Jun 11 [PubMed PMID: 19681858]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBorges-Costa J, Silva R, Gonçalves L, Filipe P, Soares de Almeida L, Marques Gomes M. Clinical and laboratory features in acute generalized pustular psoriasis: a retrospective study of 34 patients. American journal of clinical dermatology. 2011 Aug 1:12(4):271-6. doi: 10.2165/11586900-000000000-00000. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21495733]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHong SB, Kim NI. Generalized pustular psoriasis following withdrawal of short-term cyclosporin therapy for psoriatic arthritis. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2005 Jul:19(4):522-3 [PubMed PMID: 15987319]

Duckworth L, Maheshwari MB, Thomson MA. A diagnostic challenge: acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis or pustular psoriasis due to terbinafine. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 2012 Jan:37(1):24-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2011.04129.x. Epub 2011 Jul 25 [PubMed PMID: 21790726]

Kawamura A, Kinoshita MT, Suzuki H. Generalized pustular psoriasis with hypoparathyroidism. European journal of dermatology : EJD. 1999 Oct-Nov:9(7):574-6 [PubMed PMID: 10523741]

Bachelez H. Pustular psoriasis and related pustular skin diseases. The British journal of dermatology. 2018 Mar:178(3):614-618. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16232. Epub 2018 Jan 15 [PubMed PMID: 29333670]

Viguier M, Bentayeb M, Azzi J, de Pouvourville G, Gloede T, Langellier B, Massol J, Medina P, Thoma C, Bachelez H. Generalized pustular psoriasis: A nationwide population-based study using the National Health Data System in France. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2024 Jun:38(6):1131-1139. doi: 10.1111/jdv.19901. Epub 2024 Feb 25 [PubMed PMID: 38404163]

Ohkawara A, Yasuda H, Kobayashi H, Inaba Y, Ogawa H, Hashimoto I, Imamura S. Generalized pustular psoriasis in Japan: two distinct groups formed by differences in symptoms and genetic background. Acta dermato-venereologica. 1996 Jan:76(1):68-71 [PubMed PMID: 8721499]

Choon SE, Lai NM, Mohammad NA, Nanu NM, Tey KE, Chew SF. Clinical profile, morbidity, and outcome of adult-onset generalized pustular psoriasis: analysis of 102 cases seen in a tertiary hospital in Johor, Malaysia. International journal of dermatology. 2014 Jun:53(6):676-84. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12070. Epub 2013 Aug 22 [PubMed PMID: 23967807]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTwelves S, Mostafa A, Dand N, Burri E, Farkas K, Wilson R, Cooper HL, Irvine AD, Oon HH, Kingo K, Köks S, Mrowietz U, Puig L, Reynolds N, Tan ES, Tanew A, Torz K, Trattner H, Valentine M, Wahie S, Warren RB, Wright A, Bata-Csörgő Z, Szell M, Griffiths CEM, Burden AD, Choon SE, Smith CH, Barker JN, Navarini AA, Capon F. Clinical and genetic differences between pustular psoriasis subtypes. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2019 Mar:143(3):1021-1026. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.06.038. Epub 2018 Jul 21 [PubMed PMID: 30036598]

Chao PH, Cheng YW, Chung MY. Generalized pustular psoriasis in a 6-week-old infant. Pediatric dermatology. 2009 May-Jun:26(3):352-4. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2009.00918.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19706107]

Liao PB, Rubinson R, Howard R, Sanchez G, Frieden IJ. Annular pustular psoriasis--most common form of pustular psoriasis in children: report of three cases and review of the literature. Pediatric dermatology. 2002 Jan-Feb:19(1):19-25 [PubMed PMID: 11860564]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTosukhowong T, Kiratikanon S, Wonglamsam P, Netiviwat J, Innu T, Rujiwetpongstorn R, Tovanabutra N, Chiewchanvit S, Kwangsukstith C, Chuamanochan M. Epidemiology and clinical features of pustular psoriasis: A 15-year retrospective cohort. The Journal of dermatology. 2021 Dec:48(12):1931-1935. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.16164. Epub 2021 Sep 16 [PubMed PMID: 34532894]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBrunasso AM, Puntoni M, Aberer W, Delfino C, Fancelli L, Massone C. Clinical and epidemiological comparison of patients affected by palmoplantar plaque psoriasis and palmoplantar pustulosis: a case series study. The British journal of dermatology. 2013 Jun:168(6):1243-51. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12223. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23301847]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMeier-Schiesser B, Feldmeyer L, Jankovic D, Mellett M, Satoh TK, Yerly D, Navarini A, Abe R, Yawalkar N, Chung WH, French LE, Contassot E. Culprit Drugs Induce Specific IL-36 Overexpression in Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2019 Apr:139(4):848-858. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.10.023. Epub 2018 Nov 2 [PubMed PMID: 30395846]

Li L, You J, Fu X, Wang Z, Sun Y, Liu H, Zhang F. Variants of CARD14 are predisposing factors for generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) with psoriasis vulgaris but not for GPP alone in a Chinese population. The British journal of dermatology. 2019 Feb:180(2):425-426. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17392. Epub 2018 Nov 29 [PubMed PMID: 30387497]

Saggini A, Chimenti S, Chiricozzi A. IL-6 as a druggable target in psoriasis: focus on pustular variants. Journal of immunology research. 2014:2014():964069. doi: 10.1155/2014/964069. Epub 2014 Jul 13 [PubMed PMID: 25126586]

Armstrong AW, Elston CA, Elewski BE, Ferris LK, Gottlieb AB, Lebwohl MG, Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. Generalized pustular psoriasis: A consensus statement from the National Psoriasis Foundation. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2024 Apr:90(4):727-730. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.09.080. Epub 2023 Oct 13 [PubMed PMID: 37838256]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHo PH, Tsai TF. Successful treatment of refractory juvenile generalized pustular psoriasis with secukinumab monotherapy: A case report and review of published work. The Journal of dermatology. 2018 Nov:45(11):1353-1356. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14636. Epub 2018 Sep 19 [PubMed PMID: 30230584]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBoehner A, Navarini AA, Eyerich K. Generalized pustular psoriasis - a model disease for specific targeted immunotherapy, systematic review. Experimental dermatology. 2018 Oct:27(10):1067-1077. doi: 10.1111/exd.13699. Epub 2018 Jul 20 [PubMed PMID: 29852521]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceOumeish OY, Parish JL. Impetigo herpetiformis. Clinics in dermatology. 2006 Mar-Apr:24(2):101-4 [PubMed PMID: 16487882]

Morita A, Strober B, Burden AD, Choon SE, Anadkat MJ, Marrakchi S, Tsai TF, Gordon KB, Thaçi D, Zheng M, Hu N, Haeufel T, Thoma C, Lebwohl MG. Efficacy and safety of subcutaneous spesolimab for the prevention of generalised pustular psoriasis flares (Effisayil 2): an international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet (London, England). 2023 Oct 28:402(10412):1541-1551. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01378-8. Epub 2023 Sep 19 [PubMed PMID: 37738999]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMorita A, Choon SE, Bachelez H, Anadkat MJ, Marrakchi S, Zheng M, Tsai TF, Turki H, Hua H, Rajeswari S, Thoma C, Burden AD. Design of Effisayil™ 2: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Spesolimab in Preventing Flares in Patients with Generalized Pustular Psoriasis. Dermatology and therapy. 2023 Jan:13(1):347-359. doi: 10.1007/s13555-022-00835-6. Epub 2022 Nov 5 [PubMed PMID: 36333618]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRobinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, Korman NJ, Lebwohl MG, Bebo BF Jr, Kalb RE. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2012 Aug:67(2):279-88. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.01.032. Epub 2012 May 18 [PubMed PMID: 22609220]

Passeron T, Perrot JL, Jullien D, Goujon C, Ruer M, Boyé T, Villani AP, Quiles Tsimaratos N. Treatment of Severe Palmoplantar Pustular Psoriasis With Bimekizumab. JAMA dermatology. 2024 Feb 1:160(2):199-203. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.5051. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38054800]

Ibis N, Hocaoglu S, Cebicci MA, Sutbeyaz ST, Calis HT. Palmoplantar pustular psoriasis induced by adalimumab: a case report and literature review. Immunotherapy. 2015:7(7):717-20. doi: 10.2217/imt.15.45. Epub 2015 Aug 7 [PubMed PMID: 26250408]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJayasekera P, Parslew R, Al-Sharqi A. A case of tumour necrosis factor-α inhibitor- and rituximab-induced plantar pustular psoriasis that completely resolved with tocilizumab. The British journal of dermatology. 2014 Dec:171(6):1546-9. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13146. Epub 2014 Nov 3 [PubMed PMID: 24890762]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePalmou-Fontana N, Sánchez Gaviño JA, McGonagle D, García-Martinez E, Iñiguez de Onzoño Martín L. Tocilizumab-induced psoriasiform rash in rheumatoid arthritis. Dermatology (Basel, Switzerland). 2014:228(4):311-3. doi: 10.1159/000362266. Epub 2014 Jun 12 [PubMed PMID: 24942661]

Hsu L, Armstrong AW. JAK inhibitors: treatment efficacy and safety profile in patients with psoriasis. Journal of immunology research. 2014:2014():283617. doi: 10.1155/2014/283617. Epub 2014 May 5 [PubMed PMID: 24883332]

Hönigsmann H, Gschnait F, Konrad K, Wolff K. Photochemotherapy for pustular psoriasis (von Zumbusch). The British journal of dermatology. 1977 Aug:97(2):119-26 [PubMed PMID: 911672]

Choon SE, van de Kerkhof P, Gudjonsson JE, de la Cruz C, Barker J, Morita A, Romiti R, Affandi AM, Asawanonda P, Burden AD, Gonzalez C, Marrakchi S, Mowla MR, Okubo Y, Oon HH, Terui T, Tsai TF, Callis-Duffin K, Fujita H, Jo SJ, Merola J, Mrowietz U, Puig L, Thaçi D, Velásquez M, Augustin M, El Sayed M, Navarini AA, Pink A, Prinz J, Turki H, Magalhães R, Capon F, Bachelez H, IPC Pustular Psoriasis Working Group. International Consensus Definition and Diagnostic Criteria for Generalized Pustular Psoriasis From the International Psoriasis Council. JAMA dermatology. 2024 Jul 1:160(7):758-768. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2024.0915. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38691347]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSzatkowski J, Schwartz RA. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP): A review and update. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2015 Nov:73(5):843-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.017. Epub 2015 Sep 6 [PubMed PMID: 26354880]

Cheng S, Edmonds E, Ben-Gashir M, Yu RC. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis: 50 years on. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 2008 May:33(3):229-33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.02706.x. Epub 2008 Mar 18 [PubMed PMID: 18355359]

Zhou LL, Georgakopoulos JR, Ighani A, Yeung J. Systemic Monotherapy Treatments for Generalized Pustular Psoriasis: A Systematic Review. Journal of cutaneous medicine and surgery. 2018 Nov/Dec:22(6):591-601. doi: 10.1177/1203475418773358. Epub 2018 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 29707979]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHoegler KM, John AM, Handler MZ, Schwartz RA. Generalized pustular psoriasis: a review and update on treatment. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2018 Oct:32(10):1645-1651. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14949. Epub 2018 Apr 11 [PubMed PMID: 29573491]

Miyachi H, Konishi T, Kumazawa R, Matsui H, Shimizu S, Fushimi K, Matsue H, Yasunaga H. Treatments and outcomes of generalized pustular psoriasis: A cohort of 1516 patients in a nationwide inpatient database in Japan. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2022 Jun:86(6):1266-1274. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.008. Epub 2021 Jun 8 [PubMed PMID: 34116101]

Viguier M, Allez M, Zagdanski AM, Bertheau P, de Kerviler E, Rybojad M, Morel P, Dubertret L, Lémann M, Bachelez H. High frequency of cholestasis in generalized pustular psoriasis: Evidence for neutrophilic involvement of the biliary tract. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.). 2004 Aug:40(2):452-8 [PubMed PMID: 15368450]