Introduction

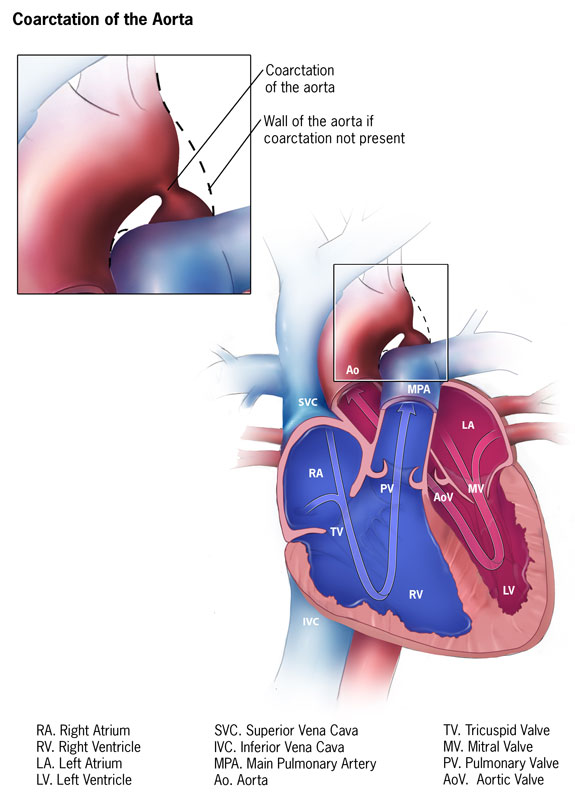

Coarctation of the aorta is a congenital cardiovascular anomaly characterized by a narrowing of the aortic lumen, typically located just distal to the origin of the left subclavian artery at the site of the ductus arteriosus (see Image. Coarctation of the Aorta). This condition results in a significant obstruction in blood flow, leading to increased pressure proximal to the constriction and reduced distal perfusion. Coarctation of the aorta presents with a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations, ranging from asymptomatic hypertension to life-threatening heart failure in infancy.

Early diagnosis and intervention are crucial, as untreated coarctation can lead to serious complications, including hypertension, left ventricular hypertrophy, aortic dissection, and intracranial hemorrhage by the third or fourth decade of life.[1][2][3] Various pathophysiologic mechanisms contribute to this persistent blood pressure issue, necessitating specific lifelong management strategies to optimize patient care.[4] Advances in imaging modalities and surgical techniques have significantly improved the prognosis for individuals with coarctation, making it a focal point of ongoing research and clinical practice. This activity provides a comprehensive overview of the etiology, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnostic approaches, and current therapeutic options for aortic coarctation, focusing on optimizing patient outcomes through multidisciplinary care.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The etiology of aortic coarctation is congenital, with the most common cause being the constriction of the aorta at the site of the ductus arteriosus or ligamentum arteriosum. This condition is often attributed to the abnormal development of the aortic arch during fetal development. Histologically, the ductus arteriosus differs significantly from the great arteries, such as the main pulmonary artery and the descending aorta. The media of the ductus arteriosus contains longitudinally and spirally arranged smooth muscle fibers, whereas the great arteries' media is composed primarily of circumferentially arranged elastic fibers.[5] Following birth, the contraction of these smooth muscle fibers leads to functional closure of the ductus, which typically begins at the pulmonary end and progresses over the first few days of life in term newborns.[5] The intima of the ductus arteriosus is also thick and irregular, with intraluminal intimal cushions forming during the third trimester, which further contributes to its postnatal constriction.

In cases where this closure process extends into the aorta, a coarctation results. Coarctation of the aorta may be more complex, involving aortic arch hypoplasia or as part of other left-sided heart lesions such as mitral stenosis, aortic stenosis, or hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Additionally, midthoracic coarctation can occur in conjunction with midaortic syndromes. Over time, the body may compensate for the narrowed aorta by developing collateral vessels around the coarcted segment.[6]

Genetic factors also play a significant role in the development of aortic coarctations. This congenital anomaly is frequently seen in patients with Turner syndrome (45,X or 45,XO), suggesting a genetic predisposition. However, most cases occur sporadically without a clear familial inheritance pattern. Environmental factors during pregnancy, such as maternal diabetes or exposure to teratogens, have also been implicated in the development of aortic coarctations, although these associations are less established. The interplay between genetic and environmental factors contributes to the varied presentation and severity of coarctations, ranging from mild cases detected incidentally to severe forms presenting with critical neonatal heart failure.

Epidemiology

Coarctation of the aorta is a relatively common congenital heart defect, accounting for approximately 5% to 7% of all congenital heart diseases and occurring more frequently in males, with a male-to-female ratio of about 2:1.[7] Coarctation of the aorta imposes an increased afterload on the left ventricle (LV), often leading to LV hypertrophy and, ultimately, heart failure if left untreated. In the United States, LV diastolic dysfunction is responsible for over half of heart failure admissions, with heart failure being the leading cause of death among adults with congenital heart disease, contributing to around 45% of cardiovascular-related deaths.[8]

Coarctation of the aorta is associated with other forms of congenital heart disease, such as a bicuspid aortic valve, Shone complex, and an interrupted aortic arch.[4] A bicuspid aortic valve occurs in 45% to 75% of patients with coarctation of the aorta. The classic Shone complex comprises a specific set of congenital heart defects, including aortic coarctation, subaortic membrane, parachute mitral valve, and a supravalvar mitral ring; this precise combination is uncommon. More frequently, patients exhibit a series of left-sided obstructions involving one or more of these lesions, often accompanied by other mitral valve abnormalities or hypoplasia of the LV.

Critical coarctation of the aorta is a severe form seen in neonates where adequate blood flow to the lower body relies on blood from the pulmonary artery through the patent ductus arteriosus into the descending aorta. A similar condition is an interrupted aortic arch, characterized by a complete discontinuity between the aortic arch and descending aorta. The location of this interruption often determines the presence of associated defects, such as an aortopulmonary window or a ventricular septal defect, found in up to 75% of cases.

The epidemiology of aortic coarctation also reveals a significant genetic component. Turner syndrome is strongly associated with coarctation of the aorta, leading to an increased risk of left-sided obstructive heart lesions; karyotype screening is recommended for females diagnosed with aortic coarctation. Additionally, first-degree relatives of individuals with obstructive left-sided heart lesions have a 10-fold increased risk of developing aortic coarctation and other congenital heart defects.[9][10] Despite advancements in early detection and treatment, coarctation of the aorta remains a significant contributor to cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, particularly when associated with other congenital anomalies.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of coarctation of the aorta is multifaceted, involving both congenital and postnatal mechanisms. The most common cause of an isolated aortic coarctation is abnormal tissue ingrowth from the ductus arteriosus into the aorta. After birth, when the ductus arteriosus begins to constrict due to increased arterial oxygen levels, this tissue can progressively narrow the aortic lumen. If this condition is not identified and treated in infancy, the intimal growth can continue, worsening the narrowing as the individual ages.[11]

In cases where aortic coarctation is associated with other congenital heart defects, upstream obstructions can impair fetal blood flow through the aorta, leading to the underdevelopment of the aortic arch.[12] Animal models of aortic coarctation also show that altered hemodynamics can influence epigenetic factors, affecting the growth and migration of endothelial cells and contributing to structural abnormalities.[13]

Coarctation of the aorta leads to significant hemodynamic consequences, most notably increased afterload on the LV, which results in LV hypertrophy and hypertension, particularly in the upper extremities. Clinically, coarctation of the aorta presents in 2 primary forms. In neonates, the sudden increase in afterload following ductus arteriosus closure can lead to LV dysfunction and shock. This presentation often occurs within the first 1 to 2 weeks of life. Neonatal pulse oximetry screening may not detect the coarctation if the ductus remains partially patent, and lower extremity saturations can appear normal, especially if other left-sided heart structures are hypoplastic.

In older children and adults, aortic coarctation typically manifests as upper extremity hypertension, which can lead to complications such as early coronary artery disease, aortic aneurysm, and cerebrovascular events. Over time, the body may develop collateral circulation to bypass the coarctation, particularly involving the intercostal arteries, which can become prominent and tortuous. However, despite these compensatory mechanisms, the long-term effects of untreated aortic coarctation include significant cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, underscoring the importance of early detection and intervention.

Histopathology

There are distinct histological differences between the ductus arteriosus and the adjacent aortic tissue that play a role in developing aortic coarctation. The media of the ductus arteriosus is primarily composed of longitudinally and spirally arranged smooth muscle fibers, in contrast to the circumferential elastic fibers of the aorta.[5] This structural difference facilitates the normal postnatal closure of the ductus arteriosus but can lead to pathological narrowing if the constriction extends into the aortic wall.

History and Physical

When evaluating a patient with suspected coarctation of the aorta, a thorough medical history and physical examination are crucial to identify key clinical features. The clinical presentation varies significantly depending on the age at diagnosis and the severity of the coarctation.

Medical History

Patients with severe coarctation of the aorta, particularly neonates, often present with symptoms of heart failure, including poor feeding, irritability, respiratory distress, and lethargy. Neonates may also exhibit signs of shock, particularly after the closure of the ductus arteriosus. In cases of less severe coarctations, older children and adults may present with hypertension, headaches, epistaxis, or leg discomfort during exertion due to reduced blood flow to the lower extremities. Obtaining a detailed family history is also important, as aortic coarctations can be associated with genetic conditions like Turner syndrome and other congenital heart diseases, including bicuspid aortic valve and Shone complex.

Physical Examination

The hallmark of aortic coarctation is a significant difference in blood pressure between the upper and lower extremities; therefore, a physical examination will often reveal elevated blood pressure in the upper extremities and diminished or delayed femoral pulses compared to brachial or radial pulses, known as brachiofemoral delay. Blood pressure measurement in all 4 extremities is recommended, with a systolic pressure gradient greater than 20 mm Hg between the upper and lower extremities, suggesting significant coarctation.

In infants, the physical examination may reveal tachypnea, hepatomegaly, and signs of poor perfusion, such as mottling or cool lower extremities. In older children and adults, a continuous or systolic murmur is often heard over the back, between the scapulae, or over the left precordium due to turbulent blood flow through the narrowed aortic segment and across collateral vessels. Additionally, patients may have a harsh systolic murmur that may radiate to the neck or back and is best heard over the left sternal border.

Evaluation

Following a comprehensive clinical assessment in a patient with a suspected coarctation of the aorta, the evaluation to confirm the diagnosis and determine the severity of the condition may include:

- Blood pressure measurement

- Simultaneous measurements in all 4 extremities are crucial. A significant difference between the upper and lower extremities (typically greater than 20 mm Hg) raises suspicion for coarctation of the aorta; measuring the ankle-brachial index can help quantify the gradient.

- Electrocardiogram

- The electrocardiogram may demonstrate increased voltage in the lateral precordial leads consistent with LV hypertrophy. LV hypertrophy results from the increased afterload that the LV must overcome due to the aortic narrowing. Diminished LV function can also be observed in neonates with severe coarctation.

- Echocardiography

- Echocardiography is typically the first-line imaging modality used to diagnose coarctation of the aorta. This study can demonstrate LV hypertrophy, mitral regurgitation, and left atrial dilation due to elevated left atrial pressures. In neonates, the LV function may be diminished. The echocardiogram can also show a narrowing in the aortic arch at the isthmus level (just beyond the left subclavian artery), with increased Doppler velocities in this region. Additionally, the aortic arch may appear hypoplastic, and abdominal aortic pulsations may be decreased with Doppler diastolic continuation/runoff beyond the coarctation site.

- Chest radiography

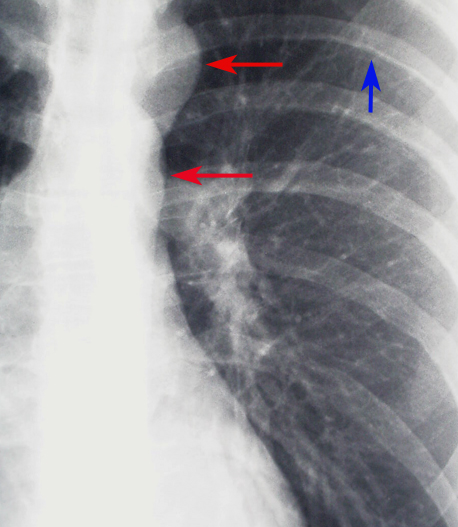

- While not definitive, certain radiographic features can strongly suggest the presence of coarctation of the aorta, guiding further diagnostic workup. One of the classic signs on a chest radiograph is the "Figure 3 sign," which represents the contour of the aorta with prestenotic dilation, indentation at the coarctation site, and poststenotic dilation. This finding, though subtle, can be an essential clue in the diagnosis. Additionally, rib notching may be seen, usually in older children and adults, due to collateral circulation that develops through intercostal arteries as a response to the aortic obstruction. This appears as bilateral, inferior rib margin erosion, typically from the third to the eighth ribs (see Image. Coarctation of the Aorta Demonstrated on Chest Radiograph).

- Advanced imaging

- Computed tomography angiography (CTA) and magnetic resonance imaging are invaluable for providing detailed anatomical information about the aortic arch and surrounding structures before and after treatment (see Images. Coarctation of the Aorta on a Computed Tomography [CT] Scan and Magnetic Resonance Imaging [MRI] and Coarctation of the Aorta Demonstrated on Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging [MRI]).[14][15] These modalities offer excellent visualization of the coarctation site, collateral vessels, and any associated anomalies, with MRI also offering the advantage of assessing flow dynamics without radiation exposure.

- Invasive testing

- Cardiac catheterization with angiography may be indicated if noninvasive imaging is inconclusive or intervention is being considered. This procedure allows for precise measurement of the pressure gradient across the coarctation and detailed anatomical assessment, essential for planning interventional procedures such as balloon angioplasty or stent placement.

- Additional studies

- In patients with suspected secondary hypertension, further testing may be needed to exclude other etiologies of hypertension. Renal ultrasound with Doppler can assess for renal artery stenosis, and laboratory tests may evaluate for endocrinopathies.

Treatment / Management

Treating and managing coarctation of the aorta aims to eliminate the narrowed segment of the aorta and restore normal blood flow. Depending on the patient's age, the severity of the coarctation, and associated cardiac or extracardiac anomalies, this can be achieved through surgical or transcatheter techniques.

Initial Stabilization

In neonates presenting with shock due to a severe coarctation, immediate stabilization is crucial; cardiorespiratory support should be initiated to address hypoperfusion and shock. Prostaglandin E1 infusion is often administered to reopen the ductus arteriosus, temporarily improving systemic blood flow. This medication can also relax the tissue at the coarctation site, which may improve blood flow across the narrowed segment. Medical support alone can sometimes lead to partial recovery of LV function, allowing for stabilization before definitive treatment.

Surgical Treatment Options

Surgery remains a primary treatment modality for coarctation of the aorta in neonates and young children. Several surgical techniques have been developed"

- Resection with end-to-end anastomosis

- This traditional approach involves the removal of the constricted segment followed by direct anastomosis of the 2 ends of the aorta. First performed by Crafoord and Gross in 1945, this method initially appeared successful but is associated with a high rate of recoarctation, particularly in neonates, with rates ranging from 41% to 51%. Due to this risk, this technique is now less commonly employed than other methods.

- Subclavian flap repair

- This technique, introduced by Waldhausen in 1966, uses the subclavian artery to create a flap sutured into the aorta to enlarge the narrowed segment. This method has a lower recoarctation rate in older children (0%-3%) but a higher rate in neonates (up to 23%). The sacrifice of the subclavian artery typically does not cause significant long-term complications but can result in arm claudication.

- Interposition graft

- This technique, introduced by Gross in 1951, involves replacing the coarcted segment with a Dacron tube graft or aortic homograft. While effective, this method is unsuitable for growing children as the graft does not grow with the patient; the technique is more appropriate for adults.

- Patch angioplasty

- Patch angioplasty involves using a prosthetic patch to widen the aorta after a longitudinal incision in the constricted segment. While this technique reduces the rate of recoarctation, it is associated with a high incidence of aortic aneurysm formation (20%-40%). Polytetrafluoroethylene materials have reduced aneurysm formation to 7%, but the recoarctation rate remains high (25%). Consequently, patch angioplasty is now less commonly employed except in complex cases requiring extensive aortic arch reconstruction.

- Extended end-to-end anastomosis

- Developed by Amato in 1977, this technique is widely used in current practice due to its lower perioperative mortality and reduced risk of recoarctation (4%-13%). The method involves excising the constricted segment and performing an extensive anastomosis that includes a portion of the aortic arch, allowing for the enlargement of a moderately hypoplastic arch.[16]

Transcatheter Techniques

Transcatheter techniques are increasingly used to manage coarctation of the aorta, particularly in older children, adolescents, and adults. They include:

- Balloon angioplasty

- Balloon angioplasty is a minimally invasive procedure that can be used as a primary treatment in neonates, children, and adults. This procedure involves inflating a balloon within the constricted aortic segment to dilate the narrowing. While this technique can be effective, it is associated with a higher risk of aortic aneurysm formation, particularly when performed in isolation.[17]

- Stent placement

- Stent placement involves inserting a metal scaffold to keep the aorta open after balloon dilation. This technique is often preferred in older children and adults due to its durability and effectiveness in preventing recoarctation. However, the long-term risk of aneurysm formation remains a concern, and patients require lifelong follow-up.

(B2)

Long-Term Management and Follow-Up

Regardless of the treatment modality, coarctation of the aorta is associated with a lifelong risk of complications, including recoarctation, aortic aneurysm formation, and hypertension. Patients also have an increased risk of developing cerebral aneurysms. Due to these risks, individuals treated for coarctation should undergo lifelong follow-up with a congenital heart disease specialist.[3][18][19] Regular imaging studies, such as echocardiography, MRI, or CT, are necessary to monitor for late complications, and blood pressure should be carefully managed to reduce the risk of hypertension-related complications.(A1)

Differential Diagnosis

Coarctation of the aorta can present diagnostic challenges due to its variable clinical manifestations, which often overlap with other conditions, particularly those causing secondary hypertension. While this anomaly is frequently diagnosed during infancy and childhood, it can remain undetected for many years, particularly in patients who present with hypertension later in life. This overlap in clinical presentation necessitates a careful differential diagnosis that includes:

- Renal parenchymal diseases

- Renal parenchymal diseases, such as glomerulonephritis or polycystic kidney disease, are among the most common causes of secondary hypertension in adolescents. Renal ultrasound and serum creatinine levels are essential investigations when renal pathology is suspected.

- Renovascular disease

- Renovascular hypertension, caused by conditions such as renal artery stenosis, is another key cause of secondary hypertension in this age group. The incidence of renovascular disease is approximately 6.69 per 100,000 person-years, with a lower incidence in patients younger than 18. Doppler ultrasonography, CTA, or MR angiography (MRA) can help identify renal artery stenosis.

- Primary aldosteronism

- This condition involves excessive production of aldosterone, leading to hypertension and hypokalemia. Diagnosis is obtained by measuring plasma aldosterone concentration and plasma renin activity measurements.

- Pheochromocytoma

- A catecholamine-secreting tumor can cause paroxysmal or sustained hypertension, often accompanied by headaches, sweating, and palpitations. Diagnosis is made through urinary or plasma metanephrines.

- Cushing disease and syndrome

- This condition is characterized by hypercortisolemia, leading to hypertension, obesity, and glucose intolerance. Diagnosis involves the dexamethasone suppression test and measurement of 24-hour urinary-free cortisol.[20]

- Other cardiovascular anomalies

- Other congenital heart diseases, such as aortic stenosis, could also present with similar symptoms, including hypertension and diminished lower extremity pulses.

Importance of Considering Coarctation of the Aorta

Given the significant overlap of symptoms, particularly hypertension, aortic coarctation should be considered a priority in the differential diagnosis, especially in adolescents presenting with secondary hypertension. This particular congenital anomaly remains a significant but often underrecognized cause of hypertension, mainly because of its variable presentation and the common association of hypertension with more prevalent renal or endocrine disorders. Given the reported prevalence of congenital heart disease, it is vital to include coarctation in the differential diagnosis when evaluating an adolescent with unexplained hypertension.

When suspected, coarctation of the aorta is best evaluated with imaging studies such as echocardiography, which can identify the characteristic narrowing of the aorta and assess for associated cardiac anomalies. CTA or MRA can also provide detailed anatomical information and guide therapeutic decisions. Early diagnosis and appropriate management are crucial for preventing the long-term complications of untreated coarctations, such as severe hypertension, heart failure, and aortic dissection.

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients who undergo a repair for coarctation of the aorta during infancy is generally favorable, with excellent early survival rates. A retrospective cohort study utilizing data from the Pediatric Cardiac Care Consortium evaluated long-term outcomes for patients who underwent surgical repair before 12 months of age between 1982 and 2003. Results from the study, which included 2424 patients, found that 20 years following the procedure, 94.5% of all patients and 95.8% of those discharged after the initial operation were still alive. Significant predictors of mortality included a surgical weight of less than 2.5 kg, the presence of a genetic syndrome, and undergoing repair before 1990.[21][22] Despite the overall positive long-term survival, over half of the deaths were linked to underlying congenital heart disease or other cardiovascular causes, indicating that while early outcomes are promising, there remains a small but persistent risk of mortality extending into early adulthood. Continuous monitoring of this cohort is necessary to assess late mortality risks further.[21]

The short-term outlook for patients postsurgery with coarctation of the aorta is excellent, but long-term survival data remain uncertain, mainly due to patients being lost to follow-up. Available data suggest that in the long term, recurrence of aortic coarctation, systemic hypertension, stroke, paraplegia, and adverse cardiac events are not uncommon. These findings underscore the importance of continuous monitoring and an interprofessional team approach to care, which is crucial to mitigate high morbidity and mortality risks.[23][24][25] Regular follow-up and coordinated care are essential to ensure the best possible outcomes for patients with coarctation of the aorta.

Complications

Coarctation of the aorta is associated with various complications that can arise before and after intervention. While surgical and transcatheter techniques have significantly improved outcomes, patients with this anomaly remain at risk for several long-term and sometimes life-threatening complications. These include:

- Systemic hypertension: Systemic hypertension is a common complication following aortic coarctation repair and can persist even when the aortic obstruction is adequately relieved. The persistence of hypertension results from long-standing arterial changes, including decreased arterial compliance, altered baroreceptor sensitivity, and abnormal vascular reactivity. Uncontrolled hypertension in these patients increases the risk of premature coronary artery disease, LV hypertrophy, heart failure, and cerebrovascular events.

- Recoarctation: Recoarctation, or the recurrence of aortic narrowing, occurs in approximately 10% to 20% of patients following initial repair. This complication is more common in patients who undergo repair during infancy and may require repeat intervention, either through balloon angioplasty or surgery. The risk of recoarctation is influenced by factors such as the patient’s age at the time of initial repair, the type of surgical technique used, and the presence of associated cardiac anomalies.

- Aneurysm formation: Aneurysms at the repair site are serious long-term complications, particularly in patients undergoing patch repair or the subclavian flap technique. These aneurysms may be true aneurysms or pseudoaneurysms and can pose a risk of rupture, leading to life-threatening hemorrhage. Aneurysms or pseudoaneurysms can develop at sites of previous surgical repair or transcatheter intervention.[26] The incidence of aneurysm formation is higher with older repair techniques and less commonly observed with contemporary surgical approaches. However, vigilant long-term surveillance with cardiac MRI is recommended, often every 5 years, to detect these aneurysms early.

- Coronary artery disease: Patients with coarctation of the aorta are at an increased risk of developing premature coronary artery disease, which can lead to angina, myocardial infarction, or sudden cardiac death. This risk persists even after successful repair and is compounded by the presence of systemic hypertension.

- Cerebrovascular events: Stroke and other cerebrovascular events are potential complications in patients with aortic coarctation, particularly in those with poorly controlled hypertension. The abnormal hemodynamics associated with the anomaly can also lead to the formation of intracranial aneurysms, which can rupture and cause subarachnoid hemorrhage.

- Aortic valve disease: Bicuspid aortic valves are common congenital anomalies in up to 50% of patients with coarctation of the aorta. They can lead to progressive aortic valve stenosis, regurgitation, or both, necessitating valve repair or replacement later in life. Additionally, they increase the risk of aortic root dilation and dissection.

- LV dysfunction: Chronic pressure overload from systemic hypertension or residual coarctation can lead to LV hypertrophy and eventual heart failure. In some cases, LV dysfunction may develop despite the absence of significant residual coarctation, underscoring the need for long-term cardiovascular management.

Surveillance and Follow-up

Given the range of potential complications, patients with coarctation of the aorta require lifelong follow-up with a congenital heart disease specialist. Regular imaging, particularly with cardiac MRI or CT, is essential to monitor for aneurysm formation, recoarctation, and other structural abnormalities. Blood pressure should be closely monitored and managed to prevent hypertensive complications.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Postoperative and rehabilitation care for patients undergoing surgical or transcatheter repair of coarctation of the aorta is critical to ensuring optimal recovery and long-term health outcomes. Management monitors early and late complications, controls blood pressure, promotes cardiovascular fitness, and ensures appropriate follow-up.

Immediate Postoperative Care

Continuous hemodynamic monitoring is essential in the immediate postoperative period, focusing on blood pressure to detect and manage potential fluctuations. Patients may experience labile blood pressure, and controlling hypertension is crucial to prevent complications such as aortic rupture, hemorrhage, or stroke. Initially, intravenous antihypertensive agents, such as sodium nitroprusside, labetalol, or esmolol, are commonly used; as the patient stabilizes, there is typically a transition to oral antihypertensive medications.

Adequate pain management is also critical to minimize sympathetic stimulation, which can worsen hypertension. Analgesic options include opioids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or regional anesthesia techniques, such as thoracic epidural analgesia. In addition to hemodynamic and pain management, respiratory care is essential, especially for patients who have undergone thoracotomy. Preventative measures to reduce the risk of atelectasis and pneumonia may include incentive spirometry, deep breathing exercises, and, if necessary, chest physiotherapy. Early mobilization is further encouraged to prevent respiratory complications and to promote recovery. Vigilant monitoring for complications is a key component of postoperative care. Early complications to watch for include bleeding, infection, chylothorax, vocal cord paralysis due to recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, and spinal cord ischemia, which may present as paraplegia.

Rehabilitation and Long-Term Care

Rehabilitation and long-term care for patients following aortic coarctation repair centers around effective blood pressure management, cardiovascular fitness, regular imaging surveillance, and psychosocial support. Persistent hypertension is common even after successful repair and is typically managed with medications such as beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, or angiotensin receptor blockers. Blood pressure should be monitored regularly, complemented by lifestyle modifications, including a heart-healthy diet, regular physical activity, and weight control. Patients are encouraged to exercise moderately to enhance cardiovascular health and prevent obesity. However, high-intensity or isometric exercises may be restricted initially due to potential increases in blood pressure and stress on the aorta. Cardiac rehabilitation programs can provide structured guidance, especially for patients requiring safe exercise practices.

Routine imaging studies, such as echocardiography, cardiac MRI, or CT angiography, are essential to monitoring potential complications like recoarctation and aneurysm formation. Imaging frequency depends on repair type and individual risk factors, with patients who have undergone patch aortoplasty or balloon angioplasty needing more frequent monitoring due to higher aneurysm risks. Screening for associated conditions is also vital, as patients with aortic coarctation may have additional cardiovascular anomalies, such as a bicuspid aortic valve, requiring continued surveillance for conditions like aortic stenosis or regurgitation. For those with hypertension or Turner syndrome, further screening for intracranial aneurysms may also be recommended.

Psychosocial support plays a crucial role, particularly for adolescents and young adults coping with the chronic nature of congenital heart disease. Counseling and support groups can offer valuable coping resources. Patient education and family involvement are also integral to long-term management. They emphasize medication adherence, recognizing warning symptoms, and attending regular follow-up appointments. Families contribute significantly to supporting the patient's overall health and well-being in this lifelong management approach.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Effective deterrence and patient education are crucial in managing coarctation of the aorta and ensuring optimal long-term outcomes. For deterrence, adherence to treatment regimens is vital. Patients should diligently follow prescribed antihypertensive medications to control blood pressure and prevent complications such as recoarctation or aortic aneurysm. Regular physical activity, a heart-healthy diet, and maintaining a healthy weight are essential lifestyle modifications for managing hypertension and overall cardiovascular health. Regular monitoring through follow-up appointments with a cardiologist is necessary to assess blood pressure, heart function, and the condition of the aorta. Scheduled imaging studies, such as echocardiography, cardiac MRI, or CT scans, help detect potential issues early. Additionally, screening for associated conditions like hypertension and aortic disease is important, as is having a robust support network to help patients adhere to treatment and manage the psychological aspects of their condition.

Patient education involves several key areas. Understanding aortic coarctation, its effects on the body, and the importance of early diagnosis and treatment helps patients and their families grasp the condition's significance. Detailed information about surgical and transcatheter treatment options, including expected outcomes and potential risks, is essential. Postoperative care education includes managing medications, recognizing symptoms of complications such as recoarctation, aortic aneurysm, or stroke, and understanding emergency protocols. Patients should be informed about long-term health management, including the importance of routine check-ups and, if applicable, cardiac rehabilitation to optimize recovery and cardiovascular health. Addressing psychosocial aspects, such as mental health support and educating family members on their role in supporting the patient, is also crucial. By implementing these strategies, the risk of complications can be minimized, and long-term health outcomes can be improved.

Pearls and Other Issues

Follow-up for patients with an aortic coarctation should be lifelong with a congenital heart specialist. Even after adequate treatment, the risk of developing hypertension increases. Regardless of the chosen therapy, there is a risk of developing aortic aneurysms, and periodic aorta imaging is required. Aneurysm development is highest after balloon angioplasty alone but is also associated with surgical repair and stent implantation. Cerebral imaging could be recommended to screen for aneurysms in adults.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective management of coarctation of the aorta requires a coordinated, interprofessional approach that leverages the unique skills and expertise of clinicians, nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals. Cllinicians must accurately diagnose and develop comprehensive treatment plans, while nurses play a critical role in patient education, monitoring, and ensuring adherence to follow-up care. Pharmacists contribute by managing medications, including antihypertensives and prostaglandin E1, and educating patients on medication adherence and potential side effects.

Interprofessional communication is crucial in ensuring all team members are informed about the patient's status and treatment plan. Regular multidisciplinary meetings can facilitate the sharing of insights, enabling early identification of potential complications and ensuring that care is patient-centered and aligned with the best clinical practices. By fostering collaboration and clear communication, the healthcare team can enhance patient safety, optimize outcomes, and improve overall team performance in managing this cardiovascular anomaly.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Coarctation of the Aorta. This illustration details the anatomy of the heart and coarctation of the aorta.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Coarctation of the Aorta Demonstrated on Chest Radiograph. This is a magnified view of coarctation of the aorta seen on a chest radiograph. The red arrows point to the classic ‘"figure 3" sign, indicating the area of the coarctation. The blue arrow shows an area of rib notching.

Contributed by H Shulman, MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Hoffman JI. The challenge in diagnosing coarctation of the aorta. Cardiovascular journal of Africa. 2018 Jul/Aug 23:29(4):252-255. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2017-053. Epub 2017 Dec 11 [PubMed PMID: 29293259]

Boris JR. Primary-care management of patients with coarctation of the aorta. Cardiology in the young. 2016 Dec:26(8):1537-1542. doi: 10.1017/S1047951116001748. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28148323]

Beckmann E, Jassar AS. Coarctation repair-redo challenges in the adults: what to do? Journal of visualized surgery. 2018:4():76. doi: 10.21037/jovs.2018.04.07. Epub 2018 Apr 23 [PubMed PMID: 29780722]

Salciccioli KB, Zachariah JP. Coarctation of the Aorta: Modern Paradigms Across the Lifespan. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex. : 1979). 2023 Oct:80(10):1970-1979. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.123.19454. Epub 2023 Jul 21 [PubMed PMID: 37476999]

Pugnaloni F, Doni D, Lucente M, Fiocchi S, Capolupo I. Ductus Arteriosus in Fetal and Perinatal Life. Journal of cardiovascular development and disease. 2024 Apr 1:11(4):. doi: 10.3390/jcdd11040113. Epub 2024 Apr 1 [PubMed PMID: 38667731]

Hanneman K, Newman B, Chan F. Congenital Variants and Anomalies of the Aortic Arch. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2017 Jan-Feb:37(1):32-51. doi: 10.1148/rg.2017160033. Epub 2016 Nov 18 [PubMed PMID: 27860551]

Jenkins NP, Ward C. Coarctation of the aorta: natural history and outcome after surgical treatment. QJM : monthly journal of the Association of Physicians. 1999 Jul:92(7):365-71 [PubMed PMID: 10627885]

Seri A, Baral N, Yousaf A, Sriramoju A, Chinta SR, Agasthi P. Outcomes of Heart Failure Hospitalizations in Adult Patients With Coarctation of Aorta: Report From National Inpatient Sample. Current problems in cardiology. 2023 Oct:48(10):101888. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2023.101888. Epub 2023 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 37343776]

Yetman AT, Starr L, Sanmann J, Wilde M, Murray M, Cramer JW. Clinical and Echocardiographic Prevalence and Detection of Congenital and Acquired Cardiac Abnormalities in Girls and Women with the Turner Syndrome. The American journal of cardiology. 2018 Jul 15:122(2):327-330. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.03.357. Epub 2018 Apr 17 [PubMed PMID: 29731120]

Ahmadi A, Mansourian M, Sabri MR, Ghaderian M, Karimi R, Roustazadeh R. Follow-up outcomes and effectiveness of stent implantation for aortic coarctation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Current problems in cardiology. 2024 Jun:49(6):102513. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2024.102513. Epub 2024 Mar 29 [PubMed PMID: 38556144]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKim YY, Andrade L, Cook SC. Aortic Coarctation. Cardiology clinics. 2020 Aug:38(3):337-351. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2020.04.003. Epub 2020 May 31 [PubMed PMID: 32622489]

Siewers RD, Ettedgui J, Pahl E, Tallman T, del Nido PJ. Coarctation and hypoplasia of the aortic arch: will the arch grow? The Annals of thoracic surgery. 1991 Sep:52(3):608-13; discussion 613-4 [PubMed PMID: 1898164]

Lim TB, Foo SYR, Chen CK. The Role of Epigenetics in Congenital Heart Disease. Genes. 2021 Mar 9:12(3):. doi: 10.3390/genes12030390. Epub 2021 Mar 9 [PubMed PMID: 33803261]

Kaya U, Colak A, Becit N, Ceviz M, Kocak H. Surgical Management of Aortic Coarctation from Infant to Adult. The Eurasian journal of medicine. 2018 Feb:50(1):14-18. doi: 10.5152/eurasianjmed.2017.17273. Epub 2017 Dec 29 [PubMed PMID: 29531485]

Conti L, Borg Savona S, Spiteri T, Degiovanni J, Borg A, Caruana M. Aortic coarctation - never too late to diagnose, never too late to treat. Images in paediatric cardiology. 2017 Jul-Sep:19(3):1-11 [PubMed PMID: 29731785]

Vasile CM, Laforest G, Bulescu C, Jalal Z, Thambo JB, Iriart X. From Crafoord's End-to-End Anastomosis Approach to Percutaneous Interventions: Coarctation of the Aorta Management Strategies and Reinterventions. Journal of clinical medicine. 2023 Nov 27:12(23):. doi: 10.3390/jcm12237350. Epub 2023 Nov 27 [PubMed PMID: 38068402]

Forbes TJ, Kim DW, Du W, Turner DR, Holzer R, Amin Z, Hijazi Z, Ghasemi A, Rome JJ, Nykanen D, Zahn E, Cowley C, Hoyer M, Waight D, Gruenstein D, Javois A, Foerster S, Kreutzer J, Sullivan N, Khan A, Owada C, Hagler D, Lim S, Canter J, Zellers T, CCISC Investigators. Comparison of surgical, stent, and balloon angioplasty treatment of native coarctation of the aorta: an observational study by the CCISC (Congenital Cardiovascular Interventional Study Consortium). Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2011 Dec 13:58(25):2664-74. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.053. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22152954]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWu Y, Jin X, Kuang H, Lv T, Li Y, Zhou Y, Wu C. Is balloon angioplasty superior to surgery in the treatment of paediatric native coarctation of the aorta: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Interactive cardiovascular and thoracic surgery. 2019 Feb 1:28(2):291-300. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivy224. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30060099]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBrzezinska-Rajszys G. Stents in treatment of aortic coarctation and recoarctation in small children. International journal of cardiology. 2018 Jul 15:263():40-41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.03.141. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29754920]

Wei L, Hu S, Gong X, Ahemaiti Y, Zhao T. Diagnosis of covert coarctation of the aorta in adolescents. Frontiers in pediatrics. 2023:11():1101607. doi: 10.3389/fped.2023.1101607. Epub 2023 Mar 21 [PubMed PMID: 37025297]

Oster ME, McCracken C, Kiener A, Aylward B, Cory M, Hunting J, Kochilas LK. Long-Term Survival of Patients With Coarctation Repaired During Infancy (from the Pediatric Cardiac Care Consortium). The American journal of cardiology. 2019 Sep 1:124(5):795-802. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.05.047. Epub 2019 Jun 6 [PubMed PMID: 31272703]

St Louis JD, Harvey BA, Menk JS, O'Brien JE Jr, Kochilas LK. Mortality and Operative Management for Patients Undergoing Repair of Coarctation of the Aorta: A Retrospective Review of the Pediatric Cardiac Care Consortium. World journal for pediatric & congenital heart surgery. 2015 Jul:6(3):431-7. doi: 10.1177/2150135115590458. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26180161]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGurvitz M, Burns KM, Brindis R, Broberg CS, Daniels CJ, Fuller SM, Honein MA, Khairy P, Kuehl KS, Landzberg MJ, Mahle WT, Mann DL, Marelli A, Newburger JW, Pearson GD, Starling RC, Tringali GR, Valente AM, Wu JC, Califf RM. Emerging Research Directions in Adult Congenital Heart Disease: A Report From an NHLBI/ACHA Working Group. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2016 Apr 26:67(16):1956-64. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.01.062. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27102511]

Ramnarine I. Role of surgery in the management of the adult patient with coarctation of the aorta. Postgraduate medical journal. 2005 Apr:81(954):243-7 [PubMed PMID: 15811888]

Lala S, Scali ST, Feezor RJ, Chandrekashar S, Giles KA, Fatima J, Berceli SA, Back MR, Huber TS, Beaver TM, Beck AW. Outcomes of thoracic endovascular aortic repair in adult coarctation patients. Journal of vascular surgery. 2018 Feb:67(2):369-381.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.06.103. Epub 2017 Sep 22 [PubMed PMID: 28947226]

Marelli A, Beauchesne L, Colman J, Ducas R, Grewal J, Keir M, Khairy P, Oechslin E, Therrien J, Vonder Muhll IF, Wald RM, Silversides C, Barron DJ, Benson L, Bernier PL, Horlick E, Ibrahim R, Martucci G, Nair K, Poirier NC, Ross HJ, Baumgartner H, Daniels CJ, Gurvitz M, Roos-Hesselink JW, Kovacs AH, McLeod CJ, Mulder BJ, Warnes CA, Webb GD. Canadian Cardiovascular Society 2022 Guidelines for Cardiovascular Interventions in Adults With Congenital Heart Disease. The Canadian journal of cardiology. 2022 Jul:38(7):862-896. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2022.03.021. Epub 2022 Apr 20 [PubMed PMID: 35460862]