Introduction

Pilomatrixoma, or calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe, is a benign tumor of the hair follicle matrix. In 1880, Malherbe and Chenantais initially described the lesion as an "epithelioma," believing its origin to be sebaceous. In 1961, Forbis and Helwing introduced the term "pilomatrixoma" after further studies identified the hair follicle matrix as the tumor's true site of origin. Some authors now suggest a panfollicular differentiation. The tumor cells can differentiate into components of the hair matrix, hair cortex, follicular infundibulum, outer root sheath, and hair bulge.

Pilomatrixoma most commonly occurs in pediatric patients on the hair-bearing areas of the head and neck but can also affect the extremities and trunk. The preauricular region is the most frequently involved site on the head. Case studies have reported occurrences in other areas, including the periocular region, eyelid, scrotum, and vulva.[1][2][3][4]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The cause of pilomatrixoma is uncertain. There are some theories on the development of pilomatrixomas, including possible mutations involving the Wnt signalling pathway, BCL-2, or CTNNB1.[5] Some cases exhibit a familial component due to the genetic nature of these lesions. An external insult, such as trauma, insect bites, or surgery, contributes to a small percentage (3.9%) of cases.[6][7][8] These lesions may occur as multiple tumors if associated with myotonic dystrophy and other disorders, such as Rubinstein-Taybi and constitutional mismatch repair deficiency (CMMRD) syndromes.[9][10][11]

Epidemiology

Traditionally considered rare, pilomatrixomas may be more common than previously thought, particularly in adolescents and young adults. An American dermatopathology laboratory identified pilomatrical neoplasms as the most common solid cutaneous tumor in individuals aged 20 years or younger.[12] A retrospective study conducted by Kinoshita et al at a single hospital in Japan reported 1,559 patients with pilomatrixomas from 2016 to 2020.[13] A multicenter study performed in Mexico from 2017 to 2023 documented 52 pediatric patients, ie, younger than 18, with 74 lesions across 2 tertiary hospitals.[14] A comprehensive review of 150 pilomatrixoma articles found a mean age at excision of 16 years and 7 months.[15]

Most studies report a slight female predominance, with a mean age of onset of 4.5 years and 90% of cases occurring before age 10. The tumor follows a bimodal distribution, with a peak incidence between birth and 20 years and a second peak between 50 and 65 years.[16] While pilomatrixoma is more commonly reported in white individuals, it remains unclear whether this trend reflects a true racial predisposition or publication bias.

Pathophysiology

The exact cause of pilomatrixoma remains unknown, but some studies link this tumor to a mutation in exon 3 of the β-catenin gene (CTNNB1). β-catenin is a component of the cadherin protein and plays a role in hair follicle differentiation. High β-catenin expression activates the Wnt signaling pathway, which is observed in proliferating matrix cells. During development, β-catenin regulates adhesion between epithelial cells.[17]

A study of 10 pilomatrixoma lesions found that all immunostaining results were strongly positive for BCL2, a protooncogene that inhibits apoptosis in both benign and malignant tumors. These findings suggest that impaired apoptosis suppression contributes to tumor development.[18]

Further research revealed that proliferating cells in human pilomatrixomas exhibit strong staining with antibodies targeting LEF-1, a marker for hair matrix cells. Additionally, S100 proteins have been identified as biochemical markers useful for characterizing pilomatrixomas.[19]

Histopathology

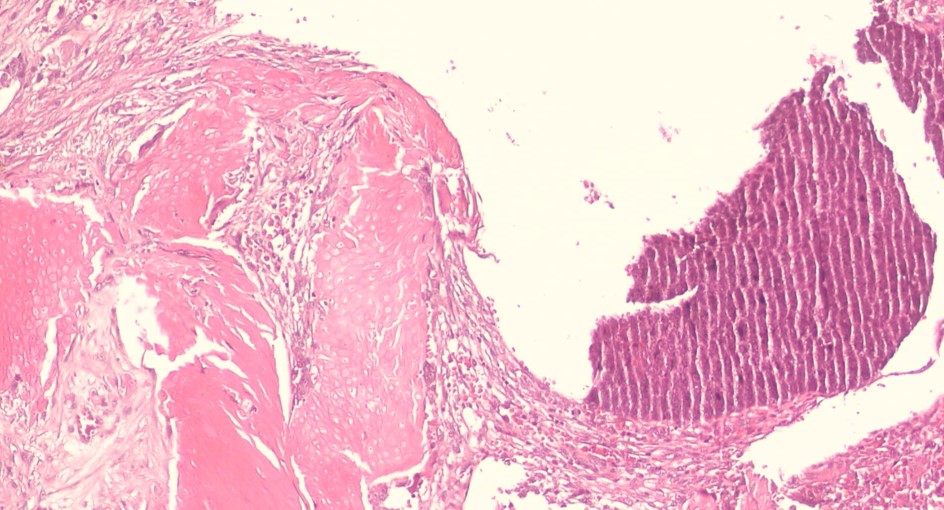

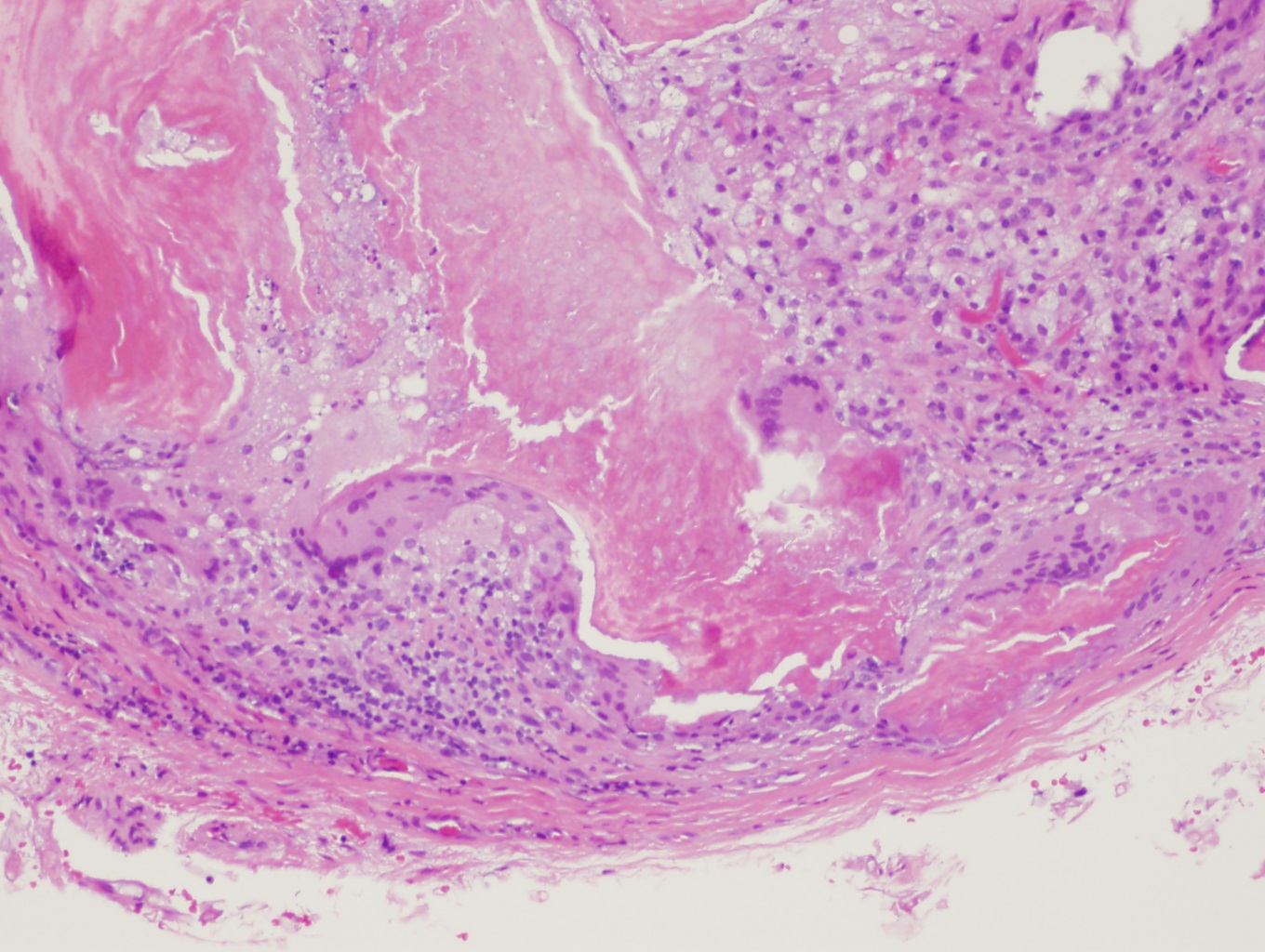

Histopathology of pilomatrixoma reveals a well-demarcated tumor enclosed by a capsule, with dermal cells extending into the subcutaneous tissue. The tumor consists of epithelial cell islands containing basaloid matrical cells, shadow (ghost or anucleated) cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm, foreign body giant cells, and calcifications (see Image. Pilomatrixoma Histopathology, High Magnification). Basophilic cells are typically concentrated along the periphery or one side of the tumor islands. Shadow cells are distinguished by a central unstained area corresponding to the absent nucleus (see Image. Pilomatrixoma Histopathology, Low Magnification). As the lesion ages, the proportion of basophilic cells decreases. Von Kossa staining detects calcium deposits in 75% of lesions.

Pilomatrix carcinoma exhibits basaloid cells, nuclear atypia, and a high mitotic rate on histology. While ghost cells are present, calcifications are less prominent. The histological similarities between pilomatrixoma and pilomatrix carcinoma can make differentiation challenging.[20]

History and Physical

Patients typically present with a slow-growing, firm, freely mobile subcutaneous tumor surrounded by a fibrous capsule. Over 70% of pilomatrixomas arise in the head and neck, but they can also occur on the upper and lower extremities, trunk, middle ear, and ovary.[21][22] While most lesions grow gradually, some cases of rapid enlargement have been reported. Pilomatrixomas are usually solitary but may occur in multiples. The overlying skin may appear blue or red, occasionally with ulcers. Although most patients are asymptomatic, some report pain or itching.

The tent sign, characterized by an angulated, tent-like appearance when the overlying skin is stretched, may be observed. The dimple sign, commonly associated with dermatofibromas, has also been noted in pilomatrixomas and involves visible epidermal retraction with lateral compression of the papule. The skin crease sign, unique to pilomatrixoma, appears as a single central longitudinal line. The anatomical basis of the skin crease sign remains unclear. This phenomenon may be related to the characteristics of pilomatrixomas, which typically present as superficial, firm-to-hard nodules that adhere to the epidermis while remaining more mobile within the subcutaneous tissue.[23] The skin crease and dimple signs appear identical at first glance but differ upon further examination.

Two cases of pilomatrixoma associated with alopecia have been reported. Familial occurrences are rare and typically linked to myotonic dystrophy. Eyelid lesions may mimic a chalazion[24]

Uncommon morphologic variants include perforating, cystic, bullous, lymphangiectatic, hornlike, keratoacanthomalike, and pigmented forms, as well as lesions with anetodermalike surface changes.[25][26][27][28] Pigmented pilomatrixoma, which contains melanin or melanocytes, is considered rare. Pilomatrixoma of the breast has been reported to resemble breast carcinoma.[29]

Evaluation

The correct diagnosis is made in only 12.5% to 55.5% of cases. Low diagnostic accuracy stems from a lack of awareness among providers and the tendency of pilomatrixoma to mimic numerous other lesions (see Differential Diagnosis). Imaging is generally not performed, but if needed, an x-ray, computed tomography, or ultrasound can help rule out vascular or lymphatic malignancies.

Ultrasound improves preoperative diagnosis, correctly identifying lesions in 76% of cases compared to 33% based on clinical evaluation alone. Plain radiography often reveals nonspecific calcifications. Ultra-high-frequency ultrasound typically shows a well-defined, heterogeneous, hypoechoic tumor located between the deep dermis and subcutis. Key features include internal echogenic foci, indicative of calcification, and a hypoechoic rim.[30][31][15][32]

Pilomatrixoma may appear as a homogeneous, well-defined intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging and a heterogeneous-to-high intensity on T2-weighted images. A computed tomography scan is particularly useful for tumors in the parotid region, revealing a well-defined subcutaneous mass with metabolic activity and microcalcifications.[33]

Fine-needle aspiration has been investigated as a diagnostic tool for pilomatrixoma. However, misinterpretation as carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, or pleomorphic adenoma with squamous metaplasia has been reported. Diagnosis via aspiration is supported by the presence of basaloid cells, ghost cells, and calcium deposits in the appropriate clinical context.[34]

Dermoscopy reveals either a bicolor yellow-white structure with diffuse linear-irregular vessels surrounding the lesion or a tricolor pattern with blue, yellow, and reddish homogeneous areas and linear irregular vessels.[35] A biopsy may be performed to identify characteristic histopathologic changes that confirm the diagnosis and rule out other conditions with similar clinical presentations.

Treatment / Management

Pilomatrixomas are benign tumors that may be observed without further need for treatment unless they exhibit concerning changes, such as increasing size or pain. When treatment is necessary, surgical excision is the preferred approach.

Recurrence occurs in 2% to 6% of cases, often due to incomplete excision. No established guidelines exist for appropriate margins. Most lesions are poorly defined, though encapsulated forms have been observed. Encapsulated tumors are less likely to recur because they can be more easily excised completely.

Local recurrence has been linked to incomplete resection, so wide excision margins of 1 to 2 cm are recommended to reduce this risk. In select pediatric cases, minimally invasive curettage may be considered to minimize scarring.[36] Secondary lesions following surgery are rare, and this risk decreases with age. Mohs micrographic surgery may be used to improve margin control.[37]

Differential Diagnosis

Pilomatrixoma can mimic a vast number of skin conditions, including the following:

- Epidermoid cyst

- Epithelioma

- Neurofibroma

- Foreign body reaction

- Calcified cyst or hematoma

- Chondroma

- Fibroxanthoma

- Osteoma cutis

- Giant cell tumor

- Basal cell carcinoma

- Branchial cleft cyst

- Calcinosis cutis

- Cutaneous melanoma

- Cutaneous pseudolymphoma

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans

- Dermoid cyst

- Eruptive vellus hair cyst

- Schwannoma

- Metastatic carcinoma

- Folliculitis

- Keratoacanthoma

- Trichilemmoma

- Trichoepithelioma

- Trichofolliculoma

- Tuberculosis

- Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma

- Insect bites

Given the extensive differential, a thorough clinical and histopathologic assessment is essential for accurate diagnosis.

Prognosis

Spontaneous regression of pilomatrixoma has never been documented. However, these neoplasms are not associated with mortality. Tumors larger than 18 cm may cause significant discomfort, but they are rare. On the other hand, pilomatrix carcinomas, though uncommon, exhibit local invasiveness and can lead to visceral metastases and mortality.

Complications

Pilomatrixomas commonly occur in cosmetically sensitive areas, which may lead to incomplete resection. Nonaesthetic scars are a potential complication of surgical excision. Pilomatrixomas typically present as solitary lesions. However, as mentioned, multiple growths can occur in association with syndromes, including myotonic dystrophy, familial adenomatous polyposis, xeroderma pigmentosum, and Gardner, Turner, Rubinstein-Taybi, Sotos, CMMRD, and basal cell nevus syndromes.

Malignant pilomatrixomas can arise from benign pilomatrixomas through transformation, but de novo tumors can also occur. Rare malignant pilomatrixomas, termed "pilomatrix carcinomas," have been reported in 125 cases. Pilomatrixomas likely to undergo malignant transformation exhibit higher cellular pleomorphism, a high mitotic rate, atypia, central necrosis, and more extensive infiltration into the skin, soft tissue, and blood and lymphatic vessels. Pilomatrix carcinomas are more common in men, typically in the 5th to 7th decade of life. Only 1 case has been reported in a child.

Similar to benign pilomatrixomas, pilomatrix carcinomas manifest as firm, nontender nodules, often on the head or neck. The tumor is locally aggressive and can metastasize in 10% of cases, with local recurrence being a predictor of metastasis. The most common site of metastasis is the lungs. Treatment typically involves excision with wide margins—5 to 30 mm—though the recurrence rate remains high at 50% to 60%. Adjuvant radiation therapy or chemotherapy is used for recurrent or metastatic disease. Mohs micrographic surgery is a suitable surgical option for preventing recurrences or metastases.[38]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Excision of all lesions is recommended for patients with numerous pilomatrixomas, and the presence of associated or familial conditions should be carefully considered. Close monitoring is necessary for the recurrence of lesions following surgical excision. Pilomatrixoma recurrence is rare but may arise following incomplete excision. Patients should be advised to monitor for any new growth at excision sites.

Pearls and Other Issues

Pilomatrixoma may be linked to Steiner myotonic dystrophy and Turner, CMMRD, Kabuki, and Gardner syndromes. In Gardner syndrome, pilomatrical change may be observed within epidermoid cysts.[39] Complete excision with clear margins is crucial to minimize the likelihood of recurrence.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Pilomatrixoma, also known as calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe, is a benign tumor of the hair follicle matrix. Most healthcare professionals may not commonly encounter this lesion, but they should know when to refer a patient to a dermatologist. Patients typically present with a slow-growing, hard, freely mobile subcutaneous tumor surrounded by a fibrous capsule. The tent sign—characterized by the flattening of part of the lesion with an angulated, tent-like appearance—may be observed when the skin is stretched. This condition most often occurs in pediatric patients in hair-bearing areas of the head and neck but can also affect the extremities and trunk, with the preauricular region being the most commonly involved part of the head.

Surgical excision is the treatment of choice when necessary. Recurrence can occur, often due to incomplete excision. Healthcare professionals, including dermatologists, plastic surgeons, oncologists, radiologists, and others involved in patient care, should possess the clinical skills and knowledge needed to diagnose and manage pilomatrixoma accurately. This expertise includes recognizing varied clinical presentations and understanding diagnostic techniques, such as ultra-high-frequency ultrasonography and histopathological evaluation. Effective teamwork has been shown to improve early detection and complete tumor clearance.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Pilomatrixoma Histopathology, High Magnification. This image shows a well-demarcated tumor enclosed by a fibrous capsule. The tumor consists of epithelial cell islands composed of basaloid matrical cells, shadow cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm, foreign body giant cells, and calcifications. Basophilic cells are concentrated along the periphery. Shadow cells are characterized by a central unstained area corresponding to the absent nucleus.

Contributed by Daniel Neelon, MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Melloni-Magnelli LF, González-Gaytán D, Sepulveda-Valenzuela M, Peña-Jiménez CY, Martínez-Leija H, Villarreal EG. Pediatric Pilomatrixomas: Four Atypical Clinical Presentations. Plastic surgery (Oakville, Ont.). 2025 Feb:33(1):133-138. doi: 10.1177/22925503231198098. Epub 2023 Aug 30 [PubMed PMID: 39876865]

Ciucă EM, Sălan AI, Camen A, Matei M, Şarlă CG, Mărgăritescu C. A patient with pilomatricoma in the parotid region: case report and review of the literature. Romanian journal of morphology and embryology = Revue roumaine de morphologie et embryologie. 2018:59(3):917-926 [PubMed PMID: 30534834]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceArora A, Nanda A, Lamba S. Cyto-Histopathological Correlation of Skin Adnexal Tumors: A Short Series. Journal of cytology. 2018 Oct-Dec:35(4):204-207. doi: 10.4103/JOC.JOC_63_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30498290]

Sidhu AS, Allende A, Gal A, Tumuluri K. Pilomatrixoma of the Periorbital Region: A Retrospective Review. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2025 Jan-Feb 01:41(1):84-89. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000002731. Epub 2024 Jul 10 [PubMed PMID: 38984650]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSekhon K, Miller-Monthrope Y, Murray C, Weinberg M. Atypical giant proliferating cystic pilomatrixoma: A case review. SAGE open medical case reports. 2025:13():2050313X251320195. doi: 10.1177/2050313X251320195. Epub 2025 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 40017994]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLloyd M, Eagle RC, Wasserman BN. Pilomatrixoma Masquerading as Giant Chalazion. Ophthalmology. 2018 Dec:125(12):1936. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.09.012. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30454715]

Pinheiro TN, Fayad FT, Arantes P, Benetti F, Guimarães G, Cintra LTA. A new case of the pilomatrixoma rare in the preauricular region and review of series of cases. Oral and maxillofacial surgery. 2018 Dec:22(4):483-488. doi: 10.1007/s10006-018-0724-8. Epub 2018 Oct 3 [PubMed PMID: 30284072]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCaprio MG, Di Serafino M, Pontillo G, Vezzali N, Rossi E, Esposito F, Zeccolini M, Vallone G. Paediatric neck ultrasonography: a pictorial essay. Journal of ultrasound. 2019 Jun:22(2):215-226. doi: 10.1007/s40477-018-0317-2. Epub 2018 Sep 5 [PubMed PMID: 30187386]

Rübben A, Wahl RU, Eggermann T, Dahl E, Ortiz-Brüchle N, Cacchi C. Mutation analysis of multiple pilomatricomas in a patient with myotonic dystrophy type 1 suggests a DM1-associated hypermutation phenotype. PloS one. 2020:15(3):e0230003. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0230003. Epub 2020 Mar 10 [PubMed PMID: 32155193]

Bueno ALA, de Souza MEV, Graziadio C, Kiszewski AE. Multiple pilomatricomas in twins with Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia. 2020 Sep-Oct:95(5):619-622. doi: 10.1016/j.abd.2020.03.011. Epub 2020 Jul 15 [PubMed PMID: 32778355]

Gupta A, George R, Aboobacker FN, ThamaraiSelvi B, Priscilla AJ. Pilomatricomas and café au lait macules as herald signs of constitutional mismatch repair deficiency (CMMRD) syndrome-A case report. Pediatric dermatology. 2020 Nov:37(6):1139-1141. doi: 10.1111/pde.14332. Epub 2020 Sep 2 [PubMed PMID: 32876971]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchwarz Y, Pitaro J, Waissbluth S, Daniel SJ. Review of pediatric head and neck pilomatrixoma. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2016 Jun:85():148-53. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2016.03.026. Epub 2016 Mar 28 [PubMed PMID: 27240514]

Kinoshita Y, Ogita A, Ito K, Saeki H. A Retrospective Study of the Clinicopathological Characteristics of Approximately 1,600 Pilomatricomas Treated at a Single Institution. Journal of Nippon Medical School = Nippon Ika Daigaku zasshi. 2024:91(4):391-401. doi: 10.1272/jnms.JNMS.2024_91-409. Epub [PubMed PMID: 39231643]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGodínez-Chaparro JA, Cruz HV, Oyorzabal-Serrano K, Ramírez-Ricarte IR. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of pilomatricomas in a Mexican pediatric population. Boletin medico del Hospital Infantil de Mexico. 2024:81(5):263-271. doi: 10.24875/BMHIM.24000067. Epub [PubMed PMID: 39378409]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJones CD, Ho W, Robertson BF, Gunn E, Morley S. Pilomatrixoma: A Comprehensive Review of the Literature. The American Journal of dermatopathology. 2018 Sep:40(9):631-641. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000001118. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30119102]

Julian CG, Bowers PW. A clinical review of 209 pilomatricomas. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1998 Aug:39(2 Pt 1):191-5 [PubMed PMID: 9704827]

Mitteldorf CATDS, Vilela RS, Fugimori ML, de Godoy CD, Coudry RA. Novel Mutations in Pilomatrixoma, CTNNB1 p.s45F, and FGFR2 p.s252L: A Report of Three Cases Diagnosed by Fine-Needle Aspiration Biopsy, with Review of the Literature. Case reports in genetics. 2020:2020():8831006. doi: 10.1155/2020/8831006. Epub 2020 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 32908727]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFarrier S, Morgan M. bcl-2 expression in pilomatricoma. The American Journal of dermatopathology. 1997 Jun:19(3):254-7 [PubMed PMID: 9185911]

Kizawa K, Toyoda M, Ito M, Morohashi M. Aberrantly differentiated cells in benign pilomatrixoma reflect the normal hair follicle: immunohistochemical analysis of Ca-binding S100A2, S100A3 and S100A6 proteins. The British journal of dermatology. 2005 Feb:152(2):314-20 [PubMed PMID: 15727645]

Kaddu S, Soyer HP, Hödl S, Kerl H. Morphological stages of pilomatricoma. The American Journal of dermatopathology. 1996 Aug:18(4):333-8 [PubMed PMID: 8879294]

Alfsen GC, Strøm EH. Pilomatrixoma of the ovary: a rare variant of mature teratoma. Histopathology. 1998 Feb:32(2):182-3 [PubMed PMID: 9543679]

Sevin K, Can Z, Yilmaz S, Saray A, Yormuk E. Pilomatrixoma of the earlobe. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 1995 Mar:21(3):245-6 [PubMed PMID: 7712097]

Kim IH, Lee SG. The skin crease sign: a diagnostic sign of pilomatricoma. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2012 Nov:67(5):e197-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.01.035. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23062909]

Hada M, Meel R, Kashyap S, Jose C. Eyelid pilomatrixoma masquerading as chalazion. Canadian journal of ophthalmology. Journal canadien d'ophtalmologie. 2017 Apr:52(2):e62-e64. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2016.08.020. Epub 2016 Oct 27 [PubMed PMID: 28457306]

Fender AB, Reale VF, Scott GA. Anetodermic pilomatricoma with perforation. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2008 Mar:58(3):535-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.03.010. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18280371]

del Pozo J, Martínez W, Yebra-Pimentel MT, Fonseca E. Lymphangiectatic variant of pilomatricoma. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2004 Sep:18(5):575-6 [PubMed PMID: 15324397]

de la Torre JP, Saiz A, García-Arpa M, Rodríguez-Peralto JL. Pilomatricomal horn: a new superficial variant of pilomatricoma. The American Journal of dermatopathology. 2006 Oct:28(5):426-8 [PubMed PMID: 17012919]

Bayle P, Bazex J, Lamant L, Lauque D, Durieu C, Albes B. Multiple perforating and non perforating pilomatricomas in a patient with Churg-Strauss syndrome and Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2004 Sep:18(5):607-10 [PubMed PMID: 15324407]

Ali MZ, Ali FZ. Pilomatrixoma breast mimicking carcinoma. Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons--Pakistan : JCPSP. 2005 Apr:15(4):248-9 [PubMed PMID: 15857602]

Li L, Xu J, Wang S, Yang J. Ultra-High-Frequency Ultrasound in the Evaluation of Paediatric Pilomatricoma Based on the Histopathologic Classification. Frontiers in medicine. 2021:8():673861. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.673861. Epub 2021 Apr 26 [PubMed PMID: 33981718]

Yi KM, Chen K, Wang L, Deng XJ, Zeng Y, Wang Y. Pilomatricoma (calcifying epithelioma): MDCT and MR imaging findings in 31 patients with radiological-pathological correlation. European journal of radiology. 2018 Sep:106():92-99. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2018.07.020. Epub 2018 Jul 21 [PubMed PMID: 30150057]

Bax D, Bax M, Pokharel S, Bogner PN. Pilomatricoma of the scalp mimicking poorly differentiated cutaneous carcinoma on positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) scan and fine-needle aspiration (FNA) cytology. JAAD case reports. 2018 Jun:4(5):446-448. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.12.006. Epub 2018 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 29984278]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDuflo S, Nicollas R, Roman S, Magalon G, Triglia JM. Pilomatrixoma of the head and neck in children: a study of 38 cases and a review of the literature. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 1998 Nov:124(11):1239-42 [PubMed PMID: 9821927]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOzcan B, Erdogan-Durmus S. Fine-needle Aspiration Biopsy of Pilomatrixoma (Cytological Features of Six Cases Histologically Approved). Journal of cytology. 2024 Jul-Sep:41(3):166-170. doi: 10.4103/joc.joc_184_23. Epub 2024 Jul 18 [PubMed PMID: 39239317]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChessa MA, Baracca MF, Rossi AN, Piraccini BM, De Pietro V, Picciola VM, Gelmetti A, Neri I. Pilomatricoma: Clinical, Dermoscopic Findings and Management in 55 Pediatric Patients and Concise Review of the Literature with Special Emphasis on Dermoscopy. Dermatology practical & conceptual. 2024 Apr 1:14(2):. doi: 10.5826/dpc.1402a140. Epub 2024 Apr 1 [PubMed PMID: 38810027]

Li Q, Zhang G. Minimally invasive curettage: A better method for removing childhood pilomatricomas than surgical excision. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2022 Jul:87(1):e3-e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.08.074. Epub 2020 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 32828858]

Sable D, Snow SN. Pilomatrix carcinoma of the back treated by mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2004 Aug:30(8):1174-6 [PubMed PMID: 15274715]

Riva HR, Sohail N, Shalabi MMK, Kelley B, Chisholm C, Tolkachjov SN. Surgical treatment of pilomatrix carcinoma: a systematic review. International journal of dermatology. 2024 Dec 4:():. doi: 10.1111/ijd.17596. Epub 2024 Dec 4 [PubMed PMID: 39628433]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRichet C, Maza A, Dreyfus I, Bourrat E, Mazereeuw-Hautier J. Childhood pilomatricomas: Associated anomalies. Pediatric dermatology. 2018 Sep:35(5):548-551. doi: 10.1111/pde.13564. Epub 2018 Jul 1 [PubMed PMID: 29962097]