Introduction

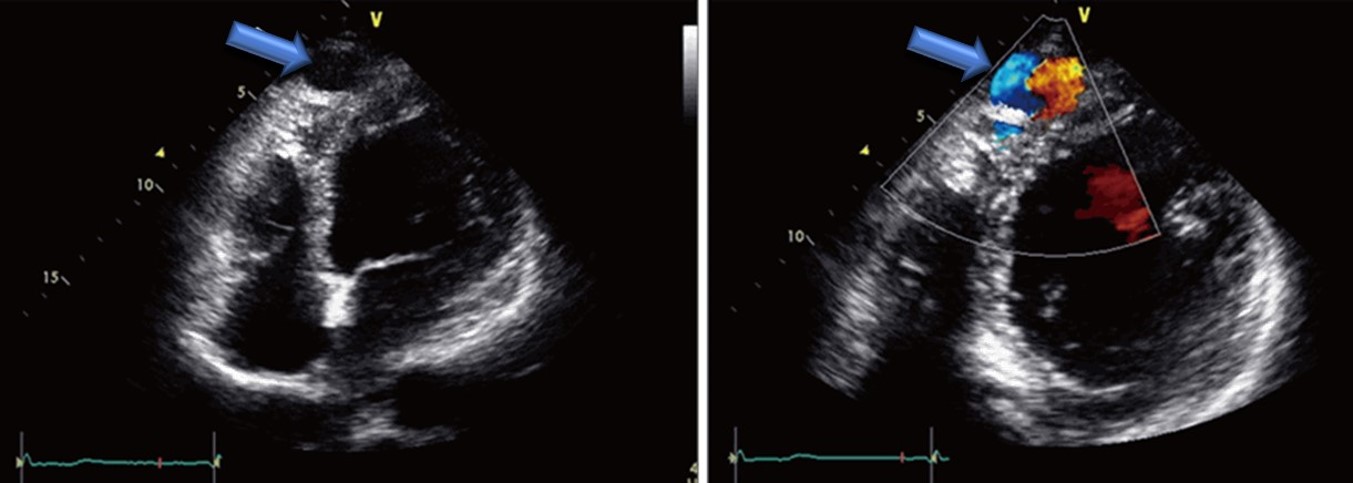

Coronary cameral fistulas are rare congenital medical conditions characterized by an abnormal connection between a coronary artery and a cardiac chamber. In contrast, coronary arteriovenous fistulas denote connections between a coronary artery and any part of the systemic or pulmonary circulation.[1] Coronary cameral fistulas are categorized anatomically based on their connection—a direct link is termed an arterioluminal fistula, whereas a connection through a sinusoidal network is referred to as an arteriosinusoidal fistula. Most coronary arteries (90%) drain into right-sided chambers or great vessels, with drainage into left-sided chambers exceedingly rare (see Image. Cardiac Ultrasound of an Adult with a Coronary Cameral Fistula).[2]

These fistulas can bypass the microcirculation, increasing 1-way blood flow between the connected structures. Although many cases are asymptomatic and discovered incidentally, larger coronary cameral fistulas can lead to complications such as arrhythmias, including atrial fibrillation; infective endocarditis; and, in rare cases, rupture or thrombosis of the fistula, which can result in sudden death.[3] They can also cause myocardial ischemia due to a coronary steal phenomenon, leading to symptoms such as angina or heart failure. The presence of the steal phenomenon is considered a sign of the hemodynamically significant consequences of the fistula.[4]

Each fistula is described by its site of origin and termination, with the most common type originating from the right coronary artery and draining into the right ventricle. Most fistulas terminate in the right ventricle or right atrium, with rare terminations in the left atrium or left ventricle.[5]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The causes of coronary cameral fistulas include:

- Abnormal embryogenesis

- This is the most common cause

- Trauma

- Stab injury or gunshot

- Invasive procedures

- Coronary angiography, pacemaker implantation, or endomyocardial biopsy

- Cardiac surgery

- Septal myomectomy [6]

Epidemiology

Coronary cameral fistulas are rare, occurring in less than 1% of the population and observed in 0.1% to 0.2% of coronary angiographic studies.[5][7] They account for 0.2% to 0.4% of congenital heart anomalies. Approximately half of the coronary vasculature anomalies in children are coronary artery fistulas. Coronary cameral fistulas can be diagnosed at any age. However, it is often identified in early childhood when an asymptomatic child or a child with heart failure symptoms presents with a heart murmur. There is no gender or race predisposition for this condition.

History and Physical

History

The clinical symptoms of a coronary cameral fistula depend on the size of the shunt. Most fistulas are asymptomatic, especially if they are small and do not compromise coronary blood flow. However, myocardial ischemia distal to the fistula can occur, known as the coronary artery steal phenomenon, leading to angina that is particularly noticeable during increased myocardial oxygen demand, such as infant feeding or adult exercise. In infants, angina manifests as diaphoresis, irritability, tachycardia, and tachypnea, whereas adults experience chest pain.[8] Coronary cameral fistulas may also present with heart failure symptoms. Infants with heart failure show signs of fatigue, tachypnea, excessive sweating during feeding, and failure to thrive. Older adults with heart failure can present with complaints of dyspnea, palpitations, fatigue, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, and lower limb swelling.

Physical Examination

Clinical examination findings in patients with coronary cameral fistula include:

- Collapsing pulse

- Wide pulse pressure

- Diffuse apex beat

- Palpable third heart sound (S3)

- A loud, continuous murmur on auscultation that peaks in mid-to-late diastole is heard best at the mid-to-lower sternal border, depending on the site of the fistula's drainage.

- Signs of heart failure

- Elevated jugular venous pressure

- S3 gallop, crepitations on auscultation of the lung bases

- Hepatomegaly

- Ascites

- Pitting edema of lower limbs

Evaluation

When the history and physical examination findings suggest a coronary cameral fistula, the diagnosis can be established with the help of the following investigations:

- Laboratory tests

- Cardiac enzymes may be elevated in patients with coronary cameral fistulas.

- B-type natriuretic peptide may also be elevated, especially in patients with heart failure.

- Chest radiograph

- This technique is typically normal; however, chamber enlargement may be observed with a large fistula.

- Signs of pulmonary congestion or interstitial edema can be present in patients with heart failure.

- Electrocardiogram

- This technique is typically normal; however, evidence of ischemia or chamber enlargement can be observed with large shunts.

- Echocardiography

- In children, transthoracic 2-dimensional (2D) and color Doppler echocardiography can help diagnose coronary cameral fistula.

- In adults, transesophageal 2D echocardiography is more sensitive in detecting the fistula.

- In a study conducted in Italy, color Doppler transesophageal echocardiography allowed diagnosis and precise localization of coronary artery fistulas in 21 patients with angiographically confirmed coronary artery fistula.[9]

- Echocardiography can also help detect myocardial ischemia, which manifests as regional or global wall motion abnormalities.

- Computed Tomography scan

- Coronary cameral fistulas can be detected noninvasively using a 64-slice multidetector computed tomography scanner, which provides high-quality 3-dimensional images of the distal coronary artery and side branches.

- A study published in 2014 by Lim et al concluded that computed tomography angiography was a useful modality for detecting coronary artery fistulas noninvasively. Moreover, coronary artery fistulas were detected in 0.9% of the study subjects, a percentage higher compared to the generally reported prevalence as detected by coronary angiography.[10][11]

- Magnetic resonance imaging

- This technique can be used to determine the exact origin and termination of the fistula.

- Cardiac catheterization with coronary angiography

- These are the tests of choice for diagnosing coronary cameral fistula.

- The exact size of the fistula can be determined by its anatomical characteristics, such as site of origin, course, site of insertion, and coronary angiography.

- This test also provides information on the hemodynamic significance of the fistula.

- Nuclear imaging

- This technique is helpful before and after operative repair to detect regions of myocardial ischemia.[12]

Treatment / Management

The management of coronary cameral fistulas depends on several factors, including the origin of the fistula, such as proximal versus distal; fistula size; and fistula anatomy. In addition, management considerations include patient's age; symptoms; the presence of complications, such as heart failure, angina, rupture, or endocarditis; and the existence of other indications for an invasive procedure.

According to the American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) 2008 guidelines for treating adults with congenital heart disease, the class 1 recommendations for the management of artery fistulas are as follows:

- In patients with a continuous murmur, echocardiography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging should be used to determine the exact origin and termination of the fistula.

- Regardless of symptoms, a large fistula should be closed percutaneously or surgically after the exact anatomy of the fistula is determined.

- Small-to-moderate–sized fistulas with complications such as ischemia, arrhythmia, ventricular dysfunction, or endarteritis should be closed either percutaneously or surgically after determining the exact anatomy of the fistula.[13] (A1)

The updated ACC/AHA 2018 guidelines for the management of adults with congenital heart disease make the following statements regarding coronary artery fistulas:

- A coronary artery fistula is an abnormal communication between a coronary artery and another cardiovascular structure, including a cardiac chamber, coronary sinus, superior vena cava, or pulmonary artery. The incidence of coronary artery fistulas is 0.1% to 0.2% in all patients undergoing coronary angiography. Fistulous communications may be congenital or acquired. Specific management strategies have been controversial, including surgical repair or catheter embolization. In a series of 46 patients treated with surgery, predominant preoperative symptoms included angina and heart failure. Notably, postoperative myocardial infarction occurred in 11% because of low flow in the dilated coronary artery proximal to fistula closure. Late survival was also significantly reduced compared to an age-matched population.

- The presence of coronary artery fistula(s) requires review by a knowledgeable team that may include congenital or noncongenital cardiologists and surgeons to determine the role of medical therapy and percutaneous or surgical closure.[14] (A1)

Small coronary cameral fistulas are typically managed through close echocardiographic or angiographic monitoring to observe any potential enlargement of feeding vessels over time. These fistulas often have a benign course, are typically asymptomatic, and may even close spontaneously.[8] Conversely, large fistulas necessitate closure, which can be achieved through transcatheter embolization or surgical intervention. The choice of approach depends on the expertise of the healthcare team managing the patient, with surgical closure preferred for large fistulas, those with multiple openings, aneurysmal dilation, or complex anatomical features unsuitable for catheterization.[15][16](B3)

Moderate-to-large fistulas without symptoms are managed based on their location. Closure, through transcatheter or surgical, is recommended for a proximal fistula. Antiplatelet therapy should be initiated after closure and continued for at least 1 year. For distal fistulas, management options include indefinite observation with antiplatelet therapy or closure followed by 1 year of antiplatelet therapy.

Although closure is advised for moderate-to-severe shunting due to potential long-term complications, debates continue regarding asymptomatic cases. Surgical closure has demonstrated effective outcomes, but catheter-based methods offer alternatives with high closure rates, minimal morbidity, and mortality. However, transcatheter closure may not be suitable for certain patient groups, particularly those with large fistulas exhibiting high-flow shunts, multiple communications and terminations, aneurysmal formation, or requiring simultaneous coronary bypass or valve surgery. Surgical complications may include myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, transient ischemic changes, and stroke.[17][18]

Prophylactic antibiotics are generally unnecessary for isolated coronary cameral fistulas but should be considered for patients with coexisting cyanotic congenital heart disease before procedures likely to cause bacteremia.[19][20](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of coronary cameral fistula sincludes the following:

- Coronary arteriovenous malformation

- Pulmonary arteriovenous malformation

- Intrathoracic systemic fistula

- Congenital systemic fistulas to the pulmonary veins

- Ruptured aneurysm of sinus of Valsalva

- Vasculitides, such as Takayasu arteritis or Kawasaki disease

Prognosis

Patients with a coronary cameral fistula typically have an average life expectancy. Studies indicate favorable prognoses with both transcatheter and surgical management approaches. The incidence of requiring additional surgery due to recurrent disease is low, affecting only about 4% of patients.

Complications

Common complications associated with coronary cameral fistula include:

- Cardiac ischemia

- Congestive heart failure

- Cardiac arrhythmia

- Infective endocarditis

- Rupture of coronary cameral fistula [6]

Complications related to the management of coronary cameral fistula (transcatheter embolization versus surgical closure) are as follows:

- Transcatheter embolization

- Coronary artery spasm

- Ventricular arrhythmia

- Coronary artery perforation or dissection

- Cardiac ischemia from coronary artery thrombosis or improper positioning of occlusive devices

- Surgical closure

- Cardiac ischemia or myocardial infarction

- Recurrence of coronary cameral fistula [5]

Deterrence and Patient Education

After hospital discharge, outpatient follow-up is crucial to monitor for signs of cardiac ischemia or recurrence of coronary artery fistula. Patients who undergo transcatheter embolization or surgical repair should receive maintenance antiplatelet therapy and possibly anticoagulant therapy for the first 6 months post-procedure until the operative surface undergoes endothelization. Extended antiplatelet therapy may benefit those with persistent aneurysmal dilation. Surgically treated patients should undergo regular stress testing and repeat angiography, especially if they experienced myocardial damage post-surgery.

Patient education is vital, covering disease understanding, management options, and potential complications. Emphasis should be placed on follow-up after hospital discharge and promptly seeking medical assistance if symptoms reoccur. Clear communication regarding adherence to antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy and the necessity of periodic stress testing and angiography is essential for ensuring optimal patient outcomes.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional team approach is essential in managing coronary cameral fistulas to ensure comprehensive patient-centered care and optimal outcomes. This team typically includes an interventional cardiologist, a cardiac surgeon, an echocardiographer, a radiologist, a pharmacist, an advanced practitioner, and nurses. The interventional cardiologist or cardiac surgeon plays a central role, leading the team in diagnosing coronary cameral fistulas using coronary angiography, which remains the gold standard. They oversee the management strategy, deciding between transcatheter embolization or surgical closure based on the patient's condition.

The echocardiographer and radiologist contribute vital noninvasive diagnostic tools such as color Doppler echocardiography and computed tomography, aiding in accurate diagnosis and procedural planning. Pharmacists collaborate to determine the optimal dosage and duration of antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy tailored to each patient's requirements, ensuring safety and efficacy. Nurses are crucial in coordinating care among team members, monitoring patient vital signs, administering medications, and providing direct patient support. This interprofessional collaboration ensures that all aspects of patient care are addressed comprehensively, leading to improved patient safety, enhanced outcomes, and efficient team performance in managing coronary cameral fistula.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Bigdelu L, Azari A, Heidari-Bakavoli A, Maadarani O. Coronary Cameral Fistula Manifested as Angina Pectoris in a 40-Year Old Female. European journal of case reports in internal medicine. 2023:10(12):004150. doi: 10.12890/2023_004150. Epub 2023 Nov 14 [PubMed PMID: 38077711]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChirumamilla Y, Brar A, Belal F, McDonald P. Large Coronary Cameral Fistula to the Left Ventricle Presenting as Congestive Heart Failure. European journal of case reports in internal medicine. 2024:11(3):004364. doi: 10.12890/2024_004364. Epub 2024 Feb 28 [PubMed PMID: 38455689]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHow WJ, Luckie M, Bratis K, Hasan R, Malik N. Evolving consequences of right coronary artery to right atrium: coronary cameral fistula-a case report. European heart journal. Case reports. 2024 May:8(5):ytae207. doi: 10.1093/ehjcr/ytae207. Epub 2024 Apr 18 [PubMed PMID: 38715625]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTommasino A, Pittorino L, Santucci S, Casenghi M, Giovannelli F, Rigattieri S, Barbato E, Berni A. Coronary Cameral Fistula With Giant Aneurysm. Korean circulation journal. 2024 Mar:54(3):160-163. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2023.0245. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38506107]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMinhas AM, Ul Haq E, Awan AA, Khan AA, Qureshi G, Balakrishna P. Coronary-Cameral Fistula Connecting the Left Anterior Descending Artery and the First Obtuse Marginal Artery to the Left Ventricle: A Rare Finding. Case reports in cardiology. 2017:2017():8071281. doi: 10.1155/2017/8071281. Epub 2017 Jan 17 [PubMed PMID: 28194284]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSharma UM, Aslam AF, Tak T. Diagnosis of coronary artery fistulas: clinical aspects and brief review of the literature. The International journal of angiology : official publication of the International College of Angiology, Inc. 2013 Sep:22(3):189-92. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1349166. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24436610]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAbdelmoneim SS, Mookadam F, Moustafa SE, Holmes DR. Coronary artery fistula with anomalous coronary artery origin: a case report. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography : official publication of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2007 Mar:20(3):333.e1-4 [PubMed PMID: 17336762]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSağlam H, Koçoğullari CU, Kaya E, Emmiler M. Congenital coronary artery fistula as a cause of angina pectoris. Turk Kardiyoloji Dernegi arsivi : Turk Kardiyoloji Derneginin yayin organidir. 2008 Dec:36(8):552-4 [PubMed PMID: 19223723]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVitarelli A, De Curtis G, Conde Y, Colantonio M, Di Benedetto G, Pecce P, De Nardo L, Squillaci E. Assessment of congenital coronary artery fistulas by transesophageal color Doppler echocardiography. The American journal of medicine. 2002 Aug 1:113(2):127-33 [PubMed PMID: 12133751]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLim JJ, Jung JI, Lee BY, Lee HG. Prevalence and types of coronary artery fistulas detected with coronary CT angiography. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2014 Sep:203(3):W237-43. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.11613. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25148179]

Zhou K, Kong L, Wang Y, Li S, Song L, Wang Z, Wu W, Chen J, Wang Y, Jin Z. Coronary artery fistula in adults: evaluation with dual-source CT coronary angiography. The British journal of radiology. 2015 May:88(1049):20140754. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20140754. Epub 2015 Mar 18 [PubMed PMID: 25784320]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChen ML, Lo HS, Su HY, Chao IM. Coronary artery fistula: assessment with multidetector computed tomography and stress myocardial single photon emission computed tomography. Clinical nuclear medicine. 2009 Feb:34(2):96-8. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e318192c497. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19352262]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWarnes CA, Williams RG, Bashore TM, Child JS, Connolly HM, Dearani JA, del Nido P, Fasules JW, Graham TP Jr, Hijazi ZM, Hunt SA, King ME, Landzberg MJ, Miner PD, Radford MJ, Walsh EP, Webb GD. ACC/AHA 2008 Guidelines for the Management of Adults with Congenital Heart Disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (writing committee to develop guidelines on the management of adults with congenital heart disease). Circulation. 2008 Dec 2:118(23):e714-833. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.190690. Epub 2008 Nov 7 [PubMed PMID: 18997169]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceStout KK, Daniels CJ, Aboulhosn JA, Bozkurt B, Broberg CS, Colman JM, Crumb SR, Dearani JA, Fuller S, Gurvitz M, Khairy P, Landzberg MJ, Saidi A, Valente AM, Van Hare GF. 2018 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Adults With Congenital Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019 Apr 2:139(14):e698-e800. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000603. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30586767]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMcMahon CJ, Nihill MR, Kovalchin JP, Mullins CE, Grifka RG. Coronary artery fistula. Management and intermediate-term outcome after transcatheter coil occlusion. Texas Heart Institute journal. 2001:28(1):21-5 [PubMed PMID: 11330735]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceArmsby LR, Keane JF, Sherwood MC, Forbess JM, Perry SB, Lock JE. Management of coronary artery fistulae. Patient selection and results of transcatheter closure. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2002 Mar 20:39(6):1026-32 [PubMed PMID: 11897446]

Albeyoglu S, Aldag M, Ciloglu U, Sargin M, Oz TK, Kutlu H, Dagsali S. Coronary Arteriovenous Fistulas in Adult Patients: Surgical Management and Outcomes. Brazilian journal of cardiovascular surgery. 2017 Jan-Feb:32(1):15-21. doi: 10.21470/1678-9741-2017-0005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28423125]

Boumaaz M, Faraj R, Lakhal Z, Benyass A, Asfalou I. Complex Coronary Artery Fistula in a Young Adult: Not Seeing the Wood for the Trees. Cureus. 2023 Nov:15(11):e49503. doi: 10.7759/cureus.49503. Epub 2023 Nov 27 [PubMed PMID: 38152799]

Edwards FH, Engelman RM, Houck P, Shahian DM, Bridges CR, Society of Thoracic Surgeons. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Practice Guideline Series: Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Cardiac Surgery, Part I: Duration. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2006 Jan:81(1):397-404 [PubMed PMID: 16368422]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceEngelman R, Shahian D, Shemin R, Guy TS, Bratzler D, Edwards F, Jacobs M, Fernando H, Bridges C, Workforce on Evidence-Based Medicine, Society of Thoracic Surgeons. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons practice guideline series: Antibiotic prophylaxis in cardiac surgery, part II: Antibiotic choice. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2007 Apr:83(4):1569-76 [PubMed PMID: 17383396]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence